1. Executive Summary

Consumer Scotland conducted an initial review of the existing evidence base to identify gaps in knowledge and consider what issues consumers in both the Private Rented Sector (PRS) and the Social Rented Sector (SRS) are experiencing. We looked, in particular, at issues around accessibility and affordability of tenancies; the condition of the properties tenants live in; and their experiences of using support and redress systems when faced with tenancy issues. This briefing sets out our initial insights, and highlights some evidence gaps as well as identifying where value may be added through further research.

We gathered the following key insights:

- The availability of affordable PRS properties is increasingly important to lower income groups as SRS supply remains short of demand. Studies found that only around 8% of advertised properties were affordable for people who received housing benefit in 2022/23, while Local Housing Allowance was frozen

- Low income PRS tenants are more likely to be dissatisfied with their tenancy than SRS tenants. This suggests that PRS tenants on low incomes may be at greater risk of detriment than if they were renting from a social landlord

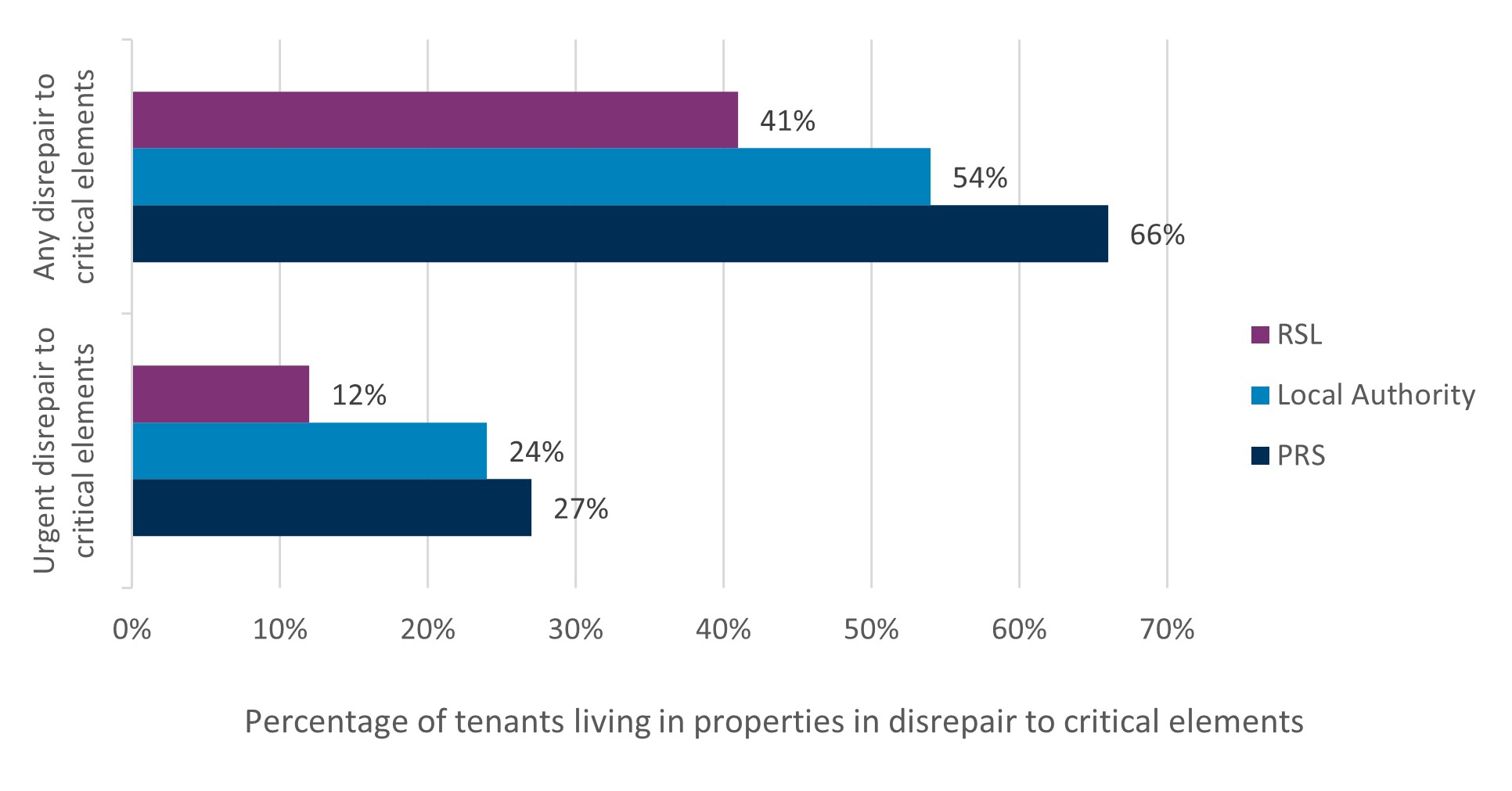

- PRS tenants are the most likely across all tenures to inhabit a property that is in a state of disrepair in relation to critical elements which are essential to weather tightness, structural stability, and preventing deterioration of the property. Local Authority tenants are nearly as likely to be faced with critical elements needing urgent repair. Registered Social Landlord tenants are the least likely to be faced with any disrepair to critical elements. Like Local Authorities, these properties are regulated by the Scottish Housing Regulator

- While PRS properties are more likely to be faced with repair issues than SRS tenants, evidence suggests they are reluctant to complain or request repairs for fear of damaging relationships with the landlord and/or eviction. Furthermore, there are concerns that in the absence of a PRS regulator, they may be exposed to lesser clarity and enforceability than SRS tenants

- While there are a number of pathways to address different issues, i.e. Rent Service Scotland when the tenant finds there is an undue rent increase, the First-Tier Tribunal’s Housing and Property Chamber remains the main option for issues PRS tenants tend to experience, i.e. repair problems. Evidence suggests that the prevalence of issues PRS tenants experience is not reflected in the number of applications they make to the Tribunal, or in their use of other resolution pathways. More evidence is required to understand how PRS tenants can be enabled to resolve issues relating to their tenancies, and what their experience is of using existing pathways

- There is currently a lack of robust data on actual rents paid by Scottish tenants and no agreed definition of affordability. However, advertised rents have risen sharply during the cost-of-living crisis and the evidence suggests that many tenants are struggling to meet housing costs

- Currently, there is insufficient reliable data to precisely monitor the supply of properties in the PRS. There are conflicting viewpoints regarding whether the sector is contracting and, if so, the extent of this

Consumer Scotland is currently conducting further research on the experience of private tenants on low incomes who are faced with tenancy issues, as well as those who advise them. We aim to identify ways to break down barriers to pursuing a solution, so that more tenants may resolve their issues. We plan to publish our conclusions and recommendations in Spring 2025.

2. Background

About us

Consumer Scotland is the statutory body for consumers in Scotland. Established by the Consumer Scotland Act 2020, we are accountable to the Scottish Parliament. The Act defines consumers as individuals and small businesses that purchase, use or receive in Scotland goods or services supplied by a business, profession, not for profit enterprise, or public body.

Our purpose is to improve outcomes for current and future consumers, and our strategic objectives are:

- To enhance understanding and awareness of consumer issues by strengthening the evidence base

- To serve the needs and aspirations of current and future consumers by inspiring and influencing the public, private and third sectors

- To enable the active participation of consumers in a fairer economy by improving access to information and support

Consumer Scotland uses data, research and analysis to inform our work on the key issues facing consumers in Scotland. In conjunction with that evidence base we seek a consumer perspective through the application of the consumer principles of access, choice, safety, information, fairness, representation, sustainability and redress.

Objectives

Consumer Scotland conducted this scoping study to inform the development of policy positions aimed at reducing harm to consumers, increasing consumer confidence, and advancing fairness, while ensuring that tenants’ interests are taken into account.

By examining and explaining how the rental market can be made fairer we will use our research and advocacy functions to seek improved outcomes for consumers, whilst considering issues around affordability and the needs of consumers in vulnerable circumstances. Having a comprehensive overview of evidence regarding key issues tenants in Scotland are facing has been helpful to flag where policy solutions may be needed, and to direct us in where we can best add value through research. We consider that this scoping study may be of similar value to other stakeholders who seek to improve outcomes for private and social tenants in Scotland.

Consumer principles

The Consumer Principles are a set of principles developed by consumer organisations in the UK and overseas.

Consumer Scotland uses the Consumer Principles as a framework through which to analyse the evidence on markets and related issues from a consumer perspective.

The Consumer Principles are:

- Access: Can people get the goods or services they need or want?

- Choice: Is there any?

- Safety: Are the goods or services dangerous to health or welfare?

- Information: Is it available, accurate and useful?

- Fairness: Are some or all consumers unfairly discriminated against?

- Representation: Do consumers have a say in how goods or services are provided?

- Redress: If things go wrong, is there a system for making things right?

- Sustainability: are consumers enabled to make sustainable choices?

Scotland’s Rental Market

Ensuring fair and affordable access to rented housing is a key issue for consumers in Scotland. It is well recognised that tenants are experiencing a number of challenges, several of which are covered below.

Following calls from a number of Local Authorities and housing organisations, the Scottish Parliament passed a motion declaring Scotland to be in a housing emergency in May 2024.[1] The Minister for Housing is leading a Housing Investment Task Force, which is exploring expanding the sources of capital that are available to support its Affordable Housing Programme. The taskforce aims to identify actions to unlock existing and new commitments to investment in housing by March 2025.[2]

The Social Rented Sector (SRS) consists of Local Authorities and Registered Social Landlords (RSLs). Registered Social Landlords are housing associations and cooperatives, as well as local authorities. In practice, and in this paper, the term RSL is used to refer to housing associations.

While Private Rented Sector (PRS) landlords can be individuals or businesses, the vast majority of PRS landlords are individuals who own only one property. Scottish Government data shows that as of April 2024, there were 238,094 private landlords registered in Scotland, with 346,767 properties in total.[3] Of these landlords, 74.9% owned only one rental property, while 12.3% owned two, and 11.7% owned three or more.

Data collected in Scotland’s Census 2022[4] shows that about one-third (35.4%) of households were renting, accounting for 887,600 households, an increase of 1.9% since 2011, when 871,300 households were renting. This includes 323,000[5] (12.9%) PRS and 564,500 (22.5%) SRS households. Rental growth was primarily driven by a rise in private lets, with a 9.5% increase from 2011. During the same period, the number of households in social rented accommodation declined, decreasing by 2.1%.

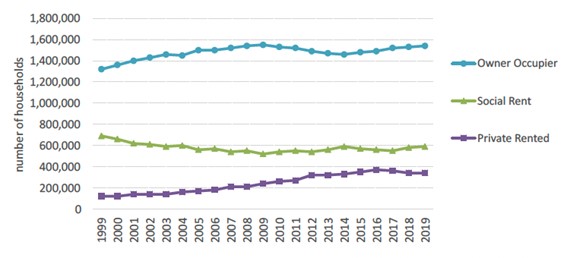

Scottish Household Survey data[6] shows this is part of a longer-term trend of the PRS increasing in size while the SRS decreases. The PRS in Scotland more than doubled between 1999 and 2019, from about 5% of all households to about 14%. Conversely, the SRS decreased from 32% of all households, in 1999 to 24% of all households, in 2019.

Chart 1. Since 1999, there has been an overall shift from social to private renting

Scottish Household Survey estimates of household tenure by year - estimated numbers of households (note this chart excludes a small proportion of "other" tenure

households)

Source: This chart was published in Scottish Government Annex A – Trends in the Size of the Private Rented Sector in Scotland - Private Sector Rent Statistics, Scotland, 2010 to 2022 Chart 1A

Consumer Duty

With the introduction of the Consumer Duty in the Consumer Scotland Act 2020, designated public authorities must now have regard to a) the impact of those decisions on consumers in Scotland; and b) the desirability of reducing harm to consumers in Scotland when making strategic decisions. [7]

Consumer Scotland has recently published draft guidance, including an impact assessment, to help relevant public authorities meet the Consumer Duty. Following a public consultation, we are finalising the guidance in time for the duty’s year-long implementation period ending on 31 March 2025.[8]

Local Authorities are subject to the duty, while RSLs are not, although they do help deliver a public service. The Scottish Housing Regulator monitors, assesses, reports and intervenes on the governance and financial wellbeing of RSLs, not of Local Authorities. The Scottish Housing Regulator’s regulatory framework includes a number of strategic-level requirements upon RSLs that do not apply to Local Authorities. As explored later in this paper, these regulatory differences may lead to a risk to divergent consumer outcomes across different housing classes.[9] The introduction of the Consumer Duty upon Local Authorities may help to mitigate any such issues over time.

Research Aims and Scope

We have sought to identify in both PRS and SRS markets:

- Where tenants face challenges

- Where disparities exist between PRS and SRS

- Where evidence gaps are to allow for a useful overview and/or comparison

This scoping study is focussed on elements relating to consumer experience rather than the broader market context. We previously articulated the need to increase the supply of affordable housing and other issues in our responses to consultations on the Housing (Scotland) Bill,[10] the Heat in Buildings Bill,[11] and a Social Housing Net Zero Standard.[12]

Our scoping has been focussed on issues which the Housing (Scotland) Bill introduced in March 2024 does not seek to resolve, but that are of importance to tenants across sectors in key points of the consumer journey. We looked at:

- Access and affordability of tenancies

- Issues with repair and maintenance and property conditions, and

- Access to redress when issues or disputes arise

Our research is focussed on housing tenancies and excludes Short-Term Lets.

3. Review Findings

Affordability and accessibility of tenancies

Tenancies have become increasingly difficult to afford

Like PRS landlords, individual social landlords set their own rents, guided by the Scottish Social Housing Charter[13] and the Housing (Scotland) Act 2001,[14] which require them to consult tenants and consider their views when setting rents and service charges. The Scottish Housing Regulator has stressed the importance of ensuring rents are affordable. However, there is currently no agreed definition of affordability.[15]

Affordability could mean different things to different groups, depending on the household type and composition, income, receipt of housing benefits, location and size of the property, and other factors. Shelter suggests that a home is affordable “if you can pay the rent or mortgage without being forced to cut back on the essentials or falling into debt.”[16] The Affordable Housing Commission looked at “what level of income spent on housing is likely to cause hardship and stress.” [17]

The Scottish Government’s expert Housing Affordability Working Group chaired by Professor Ken Gibb has been working towards a shared understanding of the term affordability, and a draft report for Scottish Ministers with recommendations was discussed in May 2024.[18]

The Scottish Government conducted a qualitative housing affordability study amongst 24 PRS and SRS tenants, published in March 2024.[19] Key insights were that any measure or definition of affordability should be:

- Clear, specific, and relative to tenants’ everyday lives and finances so they can be used and understood by tenants

- Reflect the realities of the rental market, meaning any targets much be achievable

- Emphasise fairness and dignity for tenants, as tenants should retain some funds to live and/or save

- Consider what is realistic, affordable, and allows for ‘future proofing’, with low income households in mind

Affordability has also been conceptualised with regard to housing benefit. Local Housing Allowance (LHA) is a means tested housing benefit paid to eligible tenants residing within the PRS, which is capped at the 30th percentile of median rents in the local area. LHA rates were frozen for four years from March 2020. A report by the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE) in partnership with the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH) Scotland published in November 2023 found that one in 12 (8%) of properties advertised in the financial year 2022/23 were ‘affordable’ (in the sense of there not being a financial shortfall) for private tenants receiving LHA.[20]

LHA rates were unfrozen in April 2024 and uplifted to the 30th percentile of median rents in the local area. The UK Government committed to a temporary uplift for one year, meaning recipients have been faced with insecurity and at risk of LHA decreasing by April next year. The incoming UK Government has now confirmed that LHA will remain at the 30th percentile.[21] If rents continue to increase, this makes it more likely that more low income renters experience a shortfall in this benefit to cover the rent. The LHA percentile is furthermore based on the affordability levels of advertised rent, which may not reflect the rent tenants are actually paying.

The Cost of Living (Tenant Protection) (Scotland) Act 2022 froze in-tenancy rents for both PRS and SRS tenants from September 2022 until March 2024. To our knowledge, no concrete evidence has yet been published to establish how this has impacted on the level of price increases in rents after March 2024, although letting agency ESPC has seen rents in Edinburgh increase by 5% on average since then.[22] Through the Housing Bill, the Scottish Government is seeking to provide Local Authorities with the ability to propose Rent Control Areas, which could limit and/or prevent PRS landlords in such areas from increasing the rent on their properties in-between tenancies altogether.[23] The Scottish Government published its Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment (BRIA) for the Bill in October, which includes an assessment of evidence regarding how implementation of Rent Control Areas may impact on PRS landlords’ willingness to invest.[24] It points to qualitative studies by CaCHE, RentBetter, and prior BRIA engagement around the Housing Bill, all of which suggested a risk of PRS landlords divesting from the PRS market. We consider that on balance, greater clarity is needed to determine how Rent Control Areas will impact on PRS supply, and further insight would be required to decide if and how such policies should be implemented.

On 31 October 2024, the Housing Minister announced the Scottish Government’s intention to bring forward a Stage 2 amendment setting out that rent increases in RCAs would be set at a level of CPI + 1% of the existing rent, with a maximum increase of 6% (including when CPI is 5+%).[25]

Rent levels in the PRS

Reliable and comparable rental price data, based on actual rather than advertised rents, at a local level, is needed to fully assess the affordability of Scotland’s rental market. However, there is a lack of robust evidence regarding actual rents paid by tenants in Scotland. While the Scottish Government’s Housing to 2040 strategy contains commitments to put in place mechanisms to collect accurate data on the PRS, and the New Deal for Tenants mentions use of the Scottish Landlords Register in this context,[26] we were not aware of any progress having been made at the time of publication.

A 2022 CaCHE study suggests that 30% of PRS tenants in Scotland find it difficult to afford their current rent and cites affordability as the primary concern among low-income tenants seeking improvements.[27] Another CaCHE report has highlighted affordability as a critical issue that significantly affects the rental experiences of low-income and other vulnerable groups within the PRS. A third describes a “pandemic arrears crisis”, finding that a fifth of Scottish landlords (45,000) had tenancies in arrears.[28]

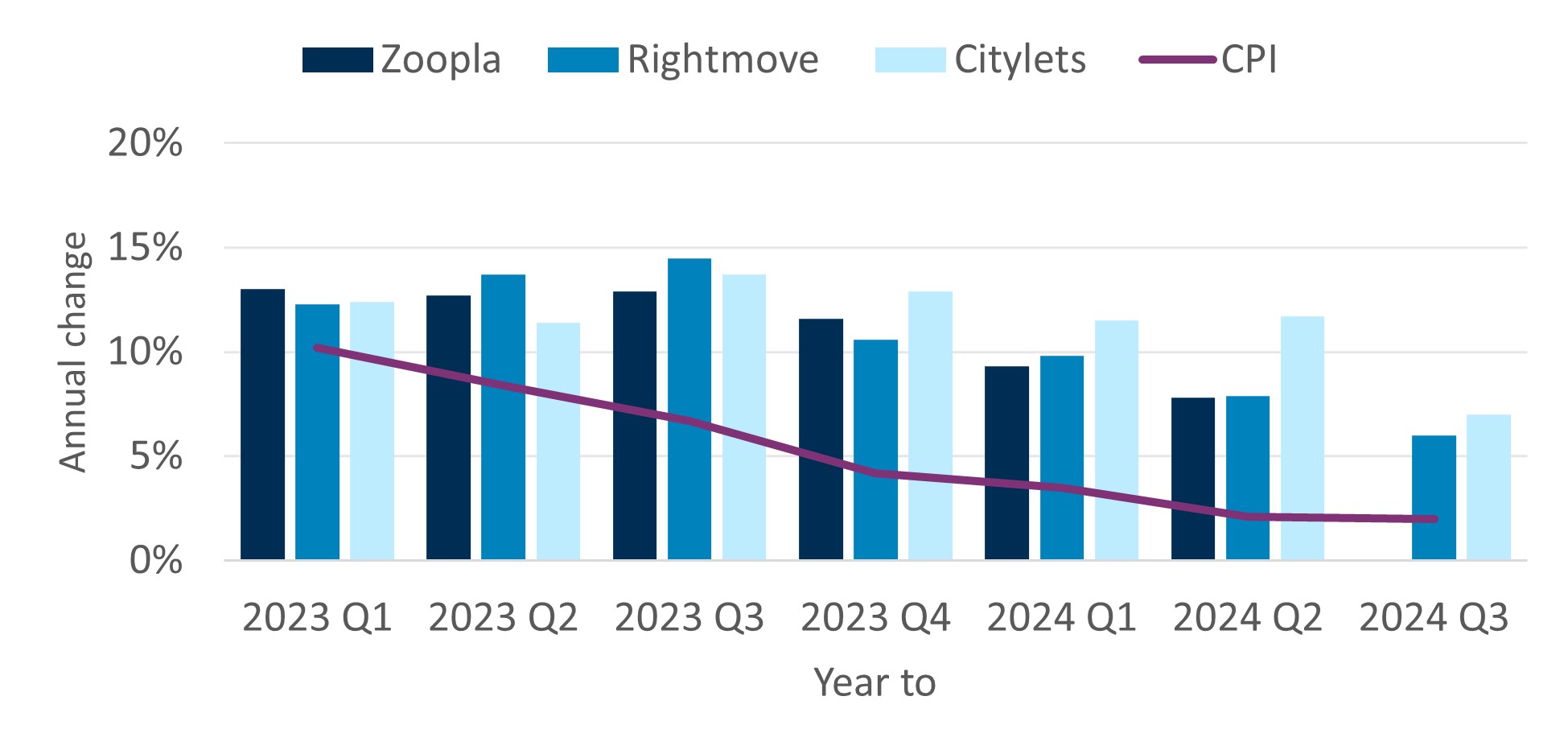

Advertised rental data shows sharp increases during the cost-of-living crisis for PRS properties. As shown in Chart 2, the available data from online property portals Citylets, Rightmove, and Zoopla indicates that the asking prices for new lets in the PRS have continued to rise in 2024, albeit at a slightly slower rate than recent historical highs.[29] For example, in Q3 2024, Rightmove suggested that PRS rent increases for new lets in Scotland had been at the lowest levels in three years. It notes a 6.3% increase in rent levels in Scotland from Q3 2023 to Q3 2024.[30] This means that rents have grown faster than the Consumer Prices Index (CPI), which compares prices of a range of consumer goods and services for the latest month with the same month a year ago. It compounds the 14.5% average rent increase in the year from Q3 2022 to Q3 2023.[31]

The Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) estimates that disposable household income also increased across this time, but not to the same extent as advertised rents. The SFC estimates indicate disposable household income grew 5.6% and 5.1% in 22/23 and 23/24 respectively. [32]

Chart 2. Rents on new tenancies continue to increase above the rate of inflation

The annual percentage increases in advertised PRS rental prices in Scotland, categorised per quarter, alongside inflation (Consumer Price Index) for the equivalent period.

Source: Zoopla Rental market Reports June 2023 - September 2024 Rightmove Rental Trends Tracker Q1 2024 – Q3 2024. Citylets Rental reports Q1 2023- Q3 2024. Note Zoopla’s Q3 2024 report not available at time of publication.

We note each agency's data will be influenced by its market coverage and that online property portal data does not cover all properties available to new tenants. For example, a survey of 1,033 PRS landlords in Scotland found just 41% used a letting agent to source tenants,[33] and properties can only be advertised on Zoopla and Rightmove by registered agents. Landlords can advertise directly on Citylets for a fee but they may also choose find tenants though more informal routes, such as word of mouth or social media. Advertised rent data also gives no insight into rents paid by current tenants.

Evidence suggests that in-tenancy rent increases have been uncommon and landlords tend to take the opportunity to implement rent increases in-between tenancies. The Wave 1 (2019/20) RentBetter Tenant Survey[34] found that 59% of tenants had not experienced a rent increase during their tenancy. A 2023 survey of PRS landlords[35] found that only 7% of landlords surveyed expected to increase rents annually and 66% reported that they would increase the rental price when re-advertising at current market rates. The temporary rent freeze and 3% rent cap were implemented through Cost of Living (Tenant Protection) (Scotland) Act 2022, which expired on 31 March 2024. In its September 2024 Market Report, Zoopla has suggested that these rent control measures have “played a part in pushing rents higher”.[36] However, the implications of recent and current policy developments on in-between and in-tenancy rent increases are not yet clear.

While existing tenants may benefit from more affordable rents and may not have experienced the level of rent increases suggested by the advertised price data so far, this could lead to tenants having reduced mobility and feeling stuck in their current tenancy as advertised prices and associated deposit requirements increase.

Rent levels in the SRS

The Scottish Housing Regulator’s National Report on the Scottish Social Housing Charter 2023/24 found that weekly rents in 2023/24 had been increased by 4.8% to £91.81 on average since the previous year. On average, Local Authority tenants paid £84.31, while RSL tenants paid an average weekly rent of £99.71.[37] The report suggests this has been compounded by a further average 6% increase in weekly rents in 2024/25; however, it is unclear whether this includes numbers provided by both Local Authorities and RSLs or Local Authorities alone. As CPI has been under 6% in all of that time (see Chart 2), this indicates that SRS rents on average have increased faster than consumer prices in general.

The Scottish Housing Regulator conducts an annual survey - the National Panel of Tenants and Service Users - to better understand the views of social tenants. In 2023/2024, it found that 49% of respondents considered their rent to be (very or fairly) good value (down from 53% in the previous year), while 35% rated it as (fairly or very) poor value (an increase from 26%).[38] This suggests that relatively more tenants than before feel like they are overpaying for the property they are renting, although little more detailed information is available on why tenants may have considered their rent to be relatively good or poor value.

The study did find that most participants mentioned the inability of a home to be efficiently heated as an indicator of a lack of quality when judging the value for money of rent. Although energy costs were cited as having either a significant or slight impact on the ability to heat their home by 63% and 25% respectively, around half of respondents also attributed their inability to heat their home to poor/ineffective heating systems (56%), no/poor insulation (49%), and poor windows/lack of double glazing (51%). The 2022 Scottish House Condition Survey found that “social housing as a whole is more energy efficient than the private sector, with a mean Energy Efficiency Rating of 70.5 compared to 65.3 for private dwellings.”[39]

Social landlords have also reported a historic peak in rent arrears, nearing £170 million at the end of March 2022 - the highest since the inception of the Scottish Social Housing Charter a decade earlier, and £23 million higher than in 2020.[40] The Scottish Housing Regulator notes that this surge underscores considerable financial strain on households.

Supply issues across both tenures impact on access

Accessing the SRS

A 2022 CaCHE study amongst PRS tenants found that nearly 1 in 5 (18%) rented privately because they were unable to access social housing, with 54% of low income tenants saying this was because they felt it was their only option.[41] While 14% expressed the desire to rent socially, 67% of those who aspired to do so believed this was either not very likely or not at all likely.

Data from the 2022 Scottish Household Survey suggests approximately 100,000 households (4%) are on a housing waiting list, while an additional 10,000 households (0.4%) applied for social housing through a choice-based letting system or a similar method within the past year.[42]

Social housing (LA and RSL units combined) accounted for just over a quarter (26%) of all new build homes completed in the year to the end of June 2024. SRS completions totalled 5,053 in this year, representing a 25% decrease (-1,649 homes) compared to the previous year. During the same period 3,501 social homes were started, a 5% decline (-199 homes) from the year before. Social housing completions were at their lowest level since the year ending June 2018, excluding the pandemic-affected year of 2020, while social housing starts reached their lowest point since the year ending June 2013.[43]

In 2023/24 there have been increases in the number of homelessness applications, the number of households assessed as homeless, the number of households and children in temporary accommodation, and the number of open applications. The number of homelessness applications and households assessed as homeless is the highest since 2011/12, with both open homelessness applications and households in temporary accommodation reaching record levels in their respective data series, dating back to 2003 and 2002.[44]

Accessing the PRS

In the PRS, landlords are allowed to charge tenants a deposit of a maximum of two months’ rent, which they must lodge with one of Scotland’s three tenancy deposit schemes within 30 working days of the beginning of the tenancy: SafeDeposits Scotland, MyDeposits Scotland, or Letting Protection Service Scotland. With deposit amounts being linked to the monthly rent, this suggests that any rent increase in-between tenancies is likely to come with an increase in the deposit. Scottish Government data shows that on 31 March 2024, a total number of 263,785 deposits were in protection, representing a total value of £209,091,045. This suggests that PRS tenants paid a mean deposit of £792.65 to secure their tenancy. Particularly for tenants on lower incomes, such sums may be prohibitive to accessing the PRS market.

In this regard, we note that the ability to access affordable PRS properties is increasingly important to lower income groups, as SRS supply remains short of demand. Evidence suggests that more individuals who previously could have expected to rent from a social landlord may now need to rent privately. For these groups in particular, higher rents and deposits in the PRS may act as a barrier to access.

Concerns around the importance of the PRS to help Local Authorities to address homelessness are illustrated by a Chartered Institute of Housing Scotland survey among Local Authorities across Scotland, to assess the implementation progress of Rapid Rehousing Transition Plans. Of these participants, 70% responded that to address homelessness effectively, Local Authorities must enhance utilisation of the PRS while there is insufficient availability of SRS housing.

Currently, there is insufficient reliable data to precisely monitor the supply of the PRS properties. There are conflicting viewpoints regarding whether the sector is contracting and, if so, the extent of this decline. The Zoopla UK Rental Market Report for September 2024 suggests that the gap between supply and demand for PRS properties across the UK decreased over the last year, but competition remained high, with 21 enquiries per rented home. This is still significantly more than the pre-pandemic average of six which was seen between 2017-2020, but much fewer than the peak in August 22, with over 40 enquiries per property.[45]

However, using data from Rightmove and Rettie, RentBetter Wave 3 research demonstrated a clear divergence between decreasing new rental listings and increasing numbers of tenant applications between 2021 and 2023, peaking around September 2022.[46] This is reflected in the finding that over the past five years, the percentage of landlords who found it quite or very easy to find tenants increased from 65% to 79% in 2024, while amongst letting agents this had increased from 70% to 88%. Over the same period, the percentage of tenants who found it quite or very easy to find a rental property had decreased from 66% to 58% - although there had been a slight increase in tenants who said they found it very easy.

Of those tenants who said they found it difficult to find a property, 67% attributed this to the number of properties being available, while 40% cited high rental prices and affordability issues. For 36% the competition for properties to let caused difficulty, 20% found it difficult to find properties where they wanted to live, and 9% found the quality of what was on offer poor. A number of other causes for difficulties were cited to a lesser degree, varying from issues finding a property that would accommodate pets to an inability to pay the deposit. Over the 5 years, the percentage of tenants in rural areas who found it difficult increased from 9% to 28%, whereas in urban areas this had stayed the same (23%).

There has been some debate about the potential impact of rent caps on the appeal of the Scottish PRS market to potential and existing landlords, and the knock-on impact on supply. The Chartered Institute of Housing Scotland has suggested the legislative landscape, including rent caps and energy performance targets, could have detrimental implications for affordability and supply.[47] An April 2023 report by estate agency Rettie, commissioned by British Property Federation, suggests that the uncertainty and adverse financial conditions resulting from the emergency rent cap in Scotland have jeopardised £3.2 billion in PRS investment. None of the investors they interviewed viewed Scotland as an "attractive place to invest”, causing Scottish cities to fall behind other UK cities in developing build-to-rent homes.[48] In addition, a recent survey by the Scottish Association of Landlords found that 34% of respondents planned to reduce their portfolios over the next decade, with 63% attributing this to regulatory issues and 60% to perceived hostility from the government and politicians.[49] However, the Scottish Government has refuted these claims, citing data from the Scottish Landlord Registration System which shows a small increase in the number of landlords in the year to January 2023.[50]

Landlord and Letting Agent Registration

The Landlord Registration System, introduced by Part 8 of the Antisocial Behaviour etc. (Scotland) Act 2004, requires PRS landlords as well as letting agents to apply for registration with their Local Authority in order to rent out properties to tenants. These requirements have resulted in a Scottish Landlord Register and a Scottish Letting Agent Register. As registration is only required every three years and landlords leaving the market may let their registration lapse, the register will contain inaccuracies. Landlords must also register the properties they are renting out and any outstanding Repairing Standards Enforcement Orders.[51]

In our response to the Housing Bill, we encouraged the Scottish Government to require recording of actual rental price data in the Scottish Landlord Register, to help collect reliable data that can be used to monitor and evaluate the impact of its policies, including potential rent control.[52]

Anyone undertaking letting agency work[53] in Scotland must be registered on the Scottish Letting Agent Register,[54] and follow the Letting Agent Code of Practice.[55] The Letting Agent Code of Practice is a set of rules that all letting agents must follow to make sure they provide a good service to tenants and landlords, i.e. when dealing with tenants, handing repairs, or ending a tenancy. No evaluation has been carried out on levels of compliance with the Code or whether there are issues around enforceability.

Following a review of the Letting Agent Registration System in light of the New Deal for Tenants, the Scottish Government proposed some minor changes in the new Housing Bill. However, these changes are of an administrative nature and generally aimed at providing letting agents with clarity rather than monitoring letting agency practices and enforcing standards.

The PRS also includes Houses of Multiple Occupation (HMOs). These are dwellings occupied by three or more unrelated people, who share bathroom or kitchen facilities in the PRS. In addition to other PRS requirements, every HMO landlord must hold an HMO licence from their Local Authority and the property must meet its physical standards.[56]

Key learnings:

- A lack of supply and a lack of confidence in availability of SRS properties means low income SRS tenants are resorting to renting privately. This increases the importance of availability of affordable PRS properties for consumers on lower incomes or with vulnerabilities. Evidence suggests that these tenants are disproportionately affected by rent increases and deposit requirements of up to two months’ rent likely exacerbate this

- While rent increases in the PRS have slowed down, tenants continue to face rent increases across both tenures. Rent increases in the PRS have so far been likely to be imposed in-between tenancies rather than during the tenancy. While evidence does not provide an insight into average rents across the total population of tenancies, or into the impact of past and proposed future rent control measures, tenants may experience challenges accessing or moving within the PRS due to availability and higher costs

Safety and quality of housing

Condition of rental properties in Scotland: overview

The Scottish House Condition Survey 2022[57] is the latest edition of the annual Scottish Government study which looks at the condition of dwellings across all tenures. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic there are no 2020 and 2021 editions. As Consumer Scotland’s review is focussed on the rented sectors, owner-occupied dwellings have been excluded from this briefing unless otherwise specified.[58]

In terms of housing conditions, we have looked at these categories:

- Any disrepair

- Disrepair of a ‘critical element’ which is essential to weather tightness, structural stability, and preventing deterioration of the property

Chart 3 below demonstrates that in 2022, PRS tenants were 60% more likely than RSL tenants to inhabit a home with disrepair to critical elements. The percentage of Local Authority properties in critical disrepair was slightly closer to PRS levels than to RSL levels. While both SRS tenures saw a decrease in this category since 2019, PRS levels had slightly increased.

RSL tenants were also by far the least likely to have critical elements in an urgent state of disrepair. This may be rooted in a higher ability to invest in maintenance, the general age of RSL housing stock, or other reasons. Further research would be needed to help identify if there is a disparity between these two subsectors and if so, what causes this and how this may be remedied. Since 2019, levels of disrepair to critical elements have decreased across all tenures.

Chart 3: PRS tenants are the most likely to experience disrepair to critical elements

The Scottish House Condition Survey 2022 indicates that Local Authority tenants are nearly as likely as PRS tenants to live in a property that requires urgent repair to critical elements.

Source: Scottish House Condition Survey 2022

Scotland’s Housing Network 2023/24 has found that, despite an increase in satisfaction with repairs completed correctly the first time, overall SRS tenant satisfaction with the quality of their homes has reduced from 89% to 86% since 2019/20.[59] While RSLs have made some progress by this measure, the Local Authority average has continued to reduce.

A 2022 study into the renting experience of PRS tenants in Scotland by CaCHE found that 25% of participants had experienced issues due to the landlord/letting agent not making repairs to the property. This was followed by 13% whose issue was that the property was in a very poor condition.[60] However, further research would be required to investigate this in more detail and consider how additional and future requirements i.e. to invest in energy efficiency measures to comply with impending net zero legislation, are likely to impact on this.

According to Wave 1 of the Nationwide Foundation’s RentBetter series (2020) most PRS respondents were satisfied with the property and the level of service they received, with only a minority of tenants experiencing poor service around repairs.[61] It found that generally, PRS tenants feel that their landlords are dealing well with day-to-day repairs (89%) as well as ongoing maintenance and upkeep (89%). However, qualitative evidence from Wave 2, published in 2022,[62] found that dissatisfaction levels of tenants on low incomes or in housing need were relatively higher. This suggests that tenants who may be in vulnerable circumstances are relatively more likely to experience tenancy-related issues. [63] As such, PRS tenants on low incomes may be at risk of detriment being compounded by their living conditions, but further research would be required to establish how this impacts on these consumers.

Circumstances associated with a better PRS renting experience were living in a rural area; renting from a landlord with one property or a small portfolio; and renting from a small landlord directly.[64] Renting through a letting agent, or from a large landlord, was associated with the lowest level of tenant satisfaction.

Damp and mould

The death of two-year old Awaab Ishak in 2020, as a result of prolonged exposure to mould in his housing association home in England, has highlighted the importance of protecting tenants from damp and mould in their properties.

The 2022 Scottish House Condition Survey found that 90% of properties (including owner-occupied) were free of damp or condensation and 91% were free from mould.[65] A breakdown per tenure was not available. While damp and mould affect a minority of housing, these issues are of great concern to tenants. This was illustrated by the 2023 CAS study In a Fix, an analysis of housing repairs advice across the CAS network. It found that water, damp and mould were the most prevalent cause of problems tenants experienced with their homes.[66]

A 2023 study by the Resolution Foundation found that across the UK, 11% of adults in the PRS and 12% of adults in the SRS lived in ‘poor quality housing’. [67] Amongst young people, this was 18%. The study defined ‘poor quality housing’ as having all three of the following issues: not being in a good state of repair, and with damp, and without properly working heating or electrics. It also found that amongst 8,831 consumers across all tenures, 30% of participants who rented privately and 27% of participants who rented socially were living in a property with damp.

The 2023/24 edition of the Scottish Housing Regulator’s National Panel of Tenants and Services Users in the SRS did not include a safety aspect and as such, we referred to 2022/23 edition.[68] This found that 6 out of 10 participants had experienced safety issues that year, and nearly 1 in 4 had experienced significant, recurrent safety concerns. Participants most commonly mentioned damp and/or mould as a significant current concern.

Housing Standards differ across tenures

In its Housing to 2040 Routemap, the Scottish Government committed to developing and consulting on a new, tenure-neutral Housing Standard in 2021.[69] This would be geared towards alleviating potential disparities in standards between rental sectors, between new and existing rental properties, and between demographic variations i.e. urban and rural/island. However, the Scottish Government’s Housing Minister has advised the Scottish Parliament that a public consultation on the tenure-neutral housing standard will now be published in 2025.[70] Until any such new standard is created, the standards below apply.

Tolerable Standard (PRS and SRS)

The Tolerable Standard sets out the minimum requirements for habitation, and applies to all residential rental properties in both the PRS and the SRS. Most of the Tolerable Standard as we know it is based on the Housing (Scotland) Act 1987 with further criteria added in 2006.[71] It determines that a house must be structurally stable; substantially free from damp; adequately illuminated, ventilated, and heated; as well as a number of other criteria. Since 1 March 2024 this includes the requirement that all dwellings must be substantially free from rising and penetrating damp.

When a property fails to meet the standard, PRS as well as SRS tenants can ask their Council to take action. We do not have an overview of how often tenants take this path, or how this impacts on tenant outcomes.

In 2019 the Tolerable Standard was extended to include the presence, type and condition of smoke, heat, and carbon monoxide alarms in properties[72] and as the first Scottish House Condition Survey since then, the 2022 edition applied this element. It assessed that 35% of PRS properties fell Below Tolerable Standard (BTS), whereas in the SRS this was 10%.[73] Had this new criterion not been implemented, both sectors would have had 2% of dwellings BTS that year. Under the old criteria in 2019 the PRS had 2% dwellings BTS, and the SRS 1%.

Scottish Housing Quality Standard (SRS)

Since 2004, SRS properties in Scotland must comply with the Scottish Housing Quality Standard (SHQS) to ensure they are energy efficient, safe and secure; not seriously damaged; and have kitchens and bathrooms that are in good condition.

This standard does not apply to PRS properties; however, the Scottish House Condition Survey does assess how many PRS properties would fail to meet the standard if it did apply in that sector, which makes for useful comparisons. While 41% of SRS properties failed to meet the SHQS criteria, it estimated that in the PRS this would be much higher, at 60%. The Scottish Housing Survey 2022 found that the main driver of SHQS failures within the social sector was failure of the energy efficiency criterion, with 29% of SRS properties not meeting this. The analysis also found that the main reason PRS properties would fail the SHQS if it applied to them was a failure to meet the Tolerable Standard criterion (35%), followed by the energy efficiency criterion at 32%.

The 2022 survey also found that PRS properties are generally less well insulated, and tend to be in lower energy efficiency bands, than SRS properties. Overall, the survey suggests that of all tenures, PRS tenants are the most likely to experience energy, safety and security issues in their homes.

The 2023/24 Annual Review[74] by Scotland’s Housing Network used data from 121 landlords, representing 88% of social housing stock in Scotland, found that social landlords have seen an improvement in complying with the SHQS. It concludes that overall, RSLs have made greater progress towards meeting these standards than Local Authorities.

Right to Repair (SRS)

Under the Scottish Secure Tenants (Right to Repair) Regulations 2002, SRS tenants have the right to have small urgent repairs carried out by their landlord within specific timescales.[75] This Right to Repair Scheme applies to qualifying repairs, with a cost of up to £350, and specifies how many working days the landlord has to make the repairs. For example, no heating or an insecure window must be fixed within one working day; limited electricity supply within three working days; and a broken kitchen extractor fan within seven days. If the issue is not resolved within the timescales, the tenant can lodge a formal complaint with the SRS landlord.

The Scottish Housing Regulator has found that in 2022/23 the average number of days to complete non-emergency repairs by Local Authority landlords was 10 working days, and by RSLs 8 days.[76] It found that 9 out of 10 repairs carried out resolved the issue the first time.

Repairing Standard (PRS)

PRS properties are subject to the Repairing Standard. The Repairing Standard was originally implemented through the Housing (Scotland) Act 2006[77] and sets out a basic level of repair that all PRS properties must meet.[78] This includes being wind and water tight, providing safe access to and use of common areas, and meeting the Tolerable Standard. Tenants can notify their landlord and, if the issue is not resolved, apply to the Housing and Property Chamber of Scotland’s First-Tier Tribunal.

Energy Efficiency

We note that in Spring 2024, the Scottish Government consulted on proposals for a Heat in Buildings Bill, which would contain minimum energy efficiency standards for PRS dwellings to be fulfilled by 2028.[79] Simultaneously, the Scottish Government consulted on proposals for a new Social Housing Net Zero Standard, providing minimum measures for SRS dwellings to be complied with by 2033.[80] Consumer Scotland continues to engage with the Scottish Government on both of these proposals, whilst also preparing to become the statutory advocate for consumers living in properties with heat networks.[81] Heat networks supply heat from a central source to consumers and can cover large areas and housing estates. Avoiding the need for individual boilers or electric heaters in every building, this will reduce emissions and achieve net zero targets. The Scottish Government aims to increase heat network coverage from 1.5% to 8% of homes in Scotland (around 650,000 homes) by 2030.[82]

Key learnings:

- There are differences in housing standards applying to SRS and PRS properties, allowing for differences in the quality of tenancy consumers are entitled to enjoy. While the Scottish Government has committed to developing and consulting on a new tenure neutral standard which might alleviate any inequities, this is not anticipated to take place until 2025

- Within the SRS, evidence suggests there are differences between the quality of housing inhabited by RSL tenants and Local Authority tenants, with RSL properties generally requiring fewer repairs. Further research would be needed to help identify if there is a disparity between the quality or condition of properties rented from Local Authorities as opposed to RSLs and if so, what causes this and how this may be remedied

- PRS tenants are generally the most likely to experience energy, safety and security issues in their homes, including the need for repairs

- PRS tenants on lower incomes or with housing needs are more likely to experience the condition of their property as unsatisfactory, which suggests a risk of vulnerabilities being compounded by their living conditions

The ability to exercise tenancy rights

Tenants and redress: overview

While it is important that safeguards are in place to ensure tenants across all sectors live in safe and secure homes, it is equally important that tenants have the awareness, confidence, and ability to exercise their rights.

Consumer Scotland research has previously found that overall, a third (37%) of adults in Scotland have low levels of legal confidence, meaning they are not confident they can achieve good outcomes across a range of common legal scenarios.[83] In addition, 24% of adults perceive the justice system in Scotland as being not very accessible. Research by the Legal Services Board in England and Wales found that anyone using legal services can be considered inherently vulnerable, primarily due to the situation that prompts their legal need, but also due to the way the legal services market works.[84] Being faced with potentially large rent increases or eviction may exacerbate existing vulnerabilities, potentially making it more difficult for tenants to understand and exercise their legal rights.

CaCHE research into the PRS identified the following groups as being more likely to experience mould/damp, issues keeping the property warm in winter, or a need for decorating/modernising :[85]

- Those in receipt of Universal Credit

- Low- and middle-income renters

- Those with a disability or long-term illness

- Female renters

RentBetter Wave 1 research found that those PRS tenants living in deprived areas, on lower incomes, or reliant on housing benefits felt less secure in their tenancies.[86] Tenants at the lower end of the market expressed a sense that if the relationship with their landlord failed or trust was compromised, their security of tenure could be at risk. Tenants lacked confidence and often feared exercising their rights due to concerns about potential repercussions, such as rent increases or losing their home in a housing system with very limited options for people on low incomes. It also found that households with older tenants (43%) were the most likely to have had problems with their tenancy in the previous five years - mostly repair issues and property condition.[87]

Further research would be required to understand whether any of these groups above are more or less likely to take action to seek redress and if so, if there are any differences in which pathway they choose.

The 2022/2023 National Panel of Tenants and Service Users found that 90% of SRS tenants would know how to report any future safety concerns, and the majority were confident their landlord would deal with this quickly (63%) and effectively (66%). However, around a third do not believe this to be the case, which could deter them from reporting issues. We are aware that the SafeDeposits Scotland Charitable Trust plans to publish its first PRS tenant survey and a separate landlord survey in Scotland in Winter 2024-25, which will increase understanding of the experiences of PRS tenants on issues including affordability, property conditions, energy efficiency, and landlord disputes. The Trust is funded by SafeDeposits Scotland, the largest deposit protection scheme in Scotland.[88]

Regulation in the rental sector

To protect SRS tenants, the Scottish Housing Regulator was established to safeguard the interests of tenants and users through the Housing (Scotland) Act 2010. As the SRS regulator, it collects Annual Assurance Statements form SRS landlords, and can take action to protect the interests of tenants or service users when a concern is raised by tenants, the landlord, third parties, or auditors.[89] It has the power to proactively engage with RSLs when it becomes aware of potentially serious issues.[90]

There is no equivalent regulator for the PRS sector. In the absence of a PRS regulator, even landlords have noted private tenants may be at risk of enjoying lesser clarity and enforceability of standards than those in the SRS.

The Chartered Institute of Housing in 2023 cited “concerns from PRS landlords that there is no authoritative source or organisation that sets out clearly what rights and responsibilities both landlords and tenants have and how issues can be resolved. This creates confusion and can lead to a poor relationship between both parties. We also understand there is ongoing concern about the lack of enforcement of existing rules and requirements and who is responsible, which landlords would like to be addressed ahead of any new regulations being introduced.”[91]

This supports the notion that moving into the PRS may leave tenants on low incomes more exposed to detriment than if they were renting from a social landlord. Further research would be required to evidence how this is impacting on PRS tenants.

In the Draft Rented Sector Strategy published in December 2021,[92] the Scottish Government committed to establishing a new PRS housing regulator by 2025, to improve housing standards and the quality of service PRS tenants receive. However, the Bill does not contain such a proposal.[93] In our response to the Housing Bill Call for Views,[94]we encouraged further consideration of whether more regulatory reforms are needed in the PRS. However, decisions on whether further regulation is needed must be based on robust evidence including stakeholder consultation, and an understanding of the nature and prevalence of issues such regulation would aim to address.

Main pathways for landlord disputes are underused

What tenants do

A Shelter Scotland review in 2020 established that there remains an evidence gap regarding the actual qualitative experiences of tenants who choose or choose not to raise and pursue disputes, and the experiences and value of different systems and forms of redress. It suggests that improvements in monitoring and evaluation would help reduce this.[95]

2022 report by the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE) found that most of 368 PRS tenants who had experienced an issue (i.e. repairs not being made, poor property condition, dispute over deposit return), 28% had opted not to raise it with their landlord or letting agent in fear of reprisals.[96] Tenants also reported moving out (22%) or living with the fact the issue has not been resolved (22%). In nearly 1 in 5 cases, the landlord offered to resolve the issue, and in 12% other methods were used. While 8% used a tenancy deposit scheme to raise an issue, only 3% made use of the Tribunal.

Generally, PRS tenants are satisfied with the condition of their property and have no reason to complain. RentBetter Wave 3 reported that both in 2019 and 2024, 9 out of 10 PRS tenants said they were either quite or very satisfied with their property, and overall, 85% of PRS tenants were satisfied with their renting experience.[97] However, it also found that most PRS tenants who experience issues did not seek any help or advice, (including contacting their landlord). Out of the 54 participants who did take action, 20 had contacted their landlord or letting agency to try and resolve the issue. 10 had sought legal advice, while 9 had contacted an advice agency and 5 their local Council.

Citizens Advice Scotland (CAS) has noted concerns, especially from PRS tenants, about the reported “threat of eviction or illegal eviction” when reporting repair issues (e.g. losing their tenancy) and as such, the problem is left and often deteriorates further. [98] CAS recommended that the Scottish Government conducts in-depth research on this topic; however, we are not aware of this being taken forward.

While most tenants do not experience issues to complain about, RentBetter Wave 2 suggests a reluctance amongst some PRS tenants who do to complain or request repairs, for fear of suffering negative consequences i.e. the landlord turning against them and/or eviction.[99] Furthermore, a CaCHE study found that such discomfort is often unrelated to the existing tenant-landlord relationship. Even when 6% of participating PRS tenants described the relationship with their landlord or letting agent as poor, more than one in every three (36%) reported being anxious about raising repairs concerns with them.[100]

Complaints that are not resolved by social landlords can be taken to the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman. The 2022/23 National Tenants and Service User panel found that 74% of participants had reported issues to their landlord in the last year and 64% of the panel indicated it concerned a repairing issue.[101] Half of those who had reported safety concerns to their landlord saw the reported issue resolved in part, and a quarter completely. We note that not every complaint is always responded to, not every response addresses every part of the complaint, and not every response results in full or partial resolution of the issue. The Scottish Housing Regulator’s 2022/23 National Report on the Scottish Social Housing Charter[102] found that the number of Stage 1 complaints responded to in full had decreased slightly, from 95% to 97%.[103]

Advice services

RentBetter’s Wave 1[104] found that while seeking guidance from an advice agency or an elected representative had been experienced as helpful, only a small number of participants had done so. There may be room to explore how tenants can be made aware and encouraged to seek advice and support from organisations and officials who are there to assist and advise them. Those who had involved their Local Authority to make a third-party application to the Tribunal did not find this effective.

Citizens Advice Scotland (CAS) caseload data cited in the RentBetter Wave 3 report indicates that in 2022/23 nearly 1 in 4 requests for housing advice consistently relates to PRS properties, and this has increased over the last three years. It is followed by nearly 1 in 5 requests regarding Local Authority housing and nearly 1 in 10 about RSL housing, Other significant topics in this regard are homelessness and environmental and neighbour issues. Shelter Scotland data also cited in the report, shows that over the last two years, around 35 - 40% of cases came in via their Private Rented Sector Helpline. Most of these requests involve repairs and maintenance issues, followed by rent. Since 2019/20 there has been a decrease in the percentage of advice requests regarding deposits, from 15% in Q1 of 2020 to 8% in Q4 of 2022/23. The research suggests this may be a positive impact of improved information provision by SafeDeposit Scotland since 2019.[105]

The report finds a need to ensure tenants are informed of their rights via accessible methods, and to encourage them to exercise their rights. It would be useful to improve understanding of how this can be done, and what information and methods would benefit tenants.

Housing and Property Chamber of the First-Tier Tribunal for Scotland

PRS tenants faced with unresolved landlord disputes can generally apply to the First-Tier Tribunal (Housing and Property Chamber). The Tribunal was intended to be “easier to understand and more user-friendly” than the Sheriff Court. To that end, an evaluation of user experience would be beneficial to help establish to what extent this has been the case. In 2018/19 the Tribunal conducted a user survey containing five high level questions, which were focussed on providing feedback to the administration and facilities rather than on the system overall.[106] It did not contain a breakdown of respondents and therefore it is unclear how many respondents were tenants, and we cannot establish what tenant’s views specifically were. Publication of more granular data would be beneficial to establish how tenants are interacting with the system and where policy changes may be needed to achieve improved outcomes for tenants.

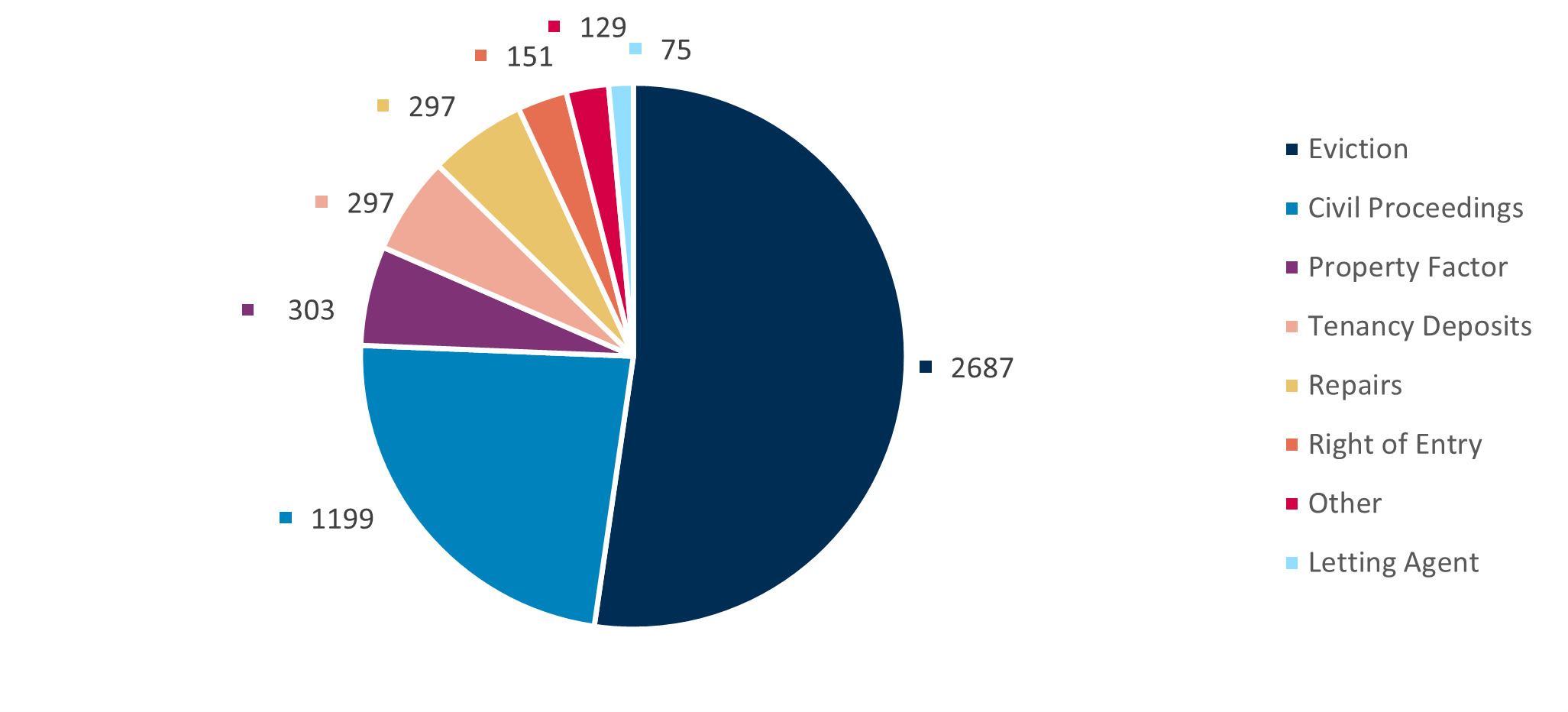

Tenants are often more likely to be respondents (party against whom the application is filed) to Tribunal cases, as the majority of cases involve applications to the Tribunal for an eviction notice and/or lodging a civil proceeding seeking a payment order (49% and 27% respectively in 2023/24, with a decrease in the number of these claims being brought together).[107] The report attributes this divergence to fewer eviction applications being based on rent arrears, and more on the landlord’s intends to sell the property.

The 2023/24 Scottish Tribunals Annual Report notes record numbers of evictions, repairs, and property factor cases. While we note that temporary restrictions on evictions will have impacted on some figures, the largest percentage increases were found in the following categories:

- Repairing Standards (+38%)

- Evictions (+19%)

- Property factor applications (19% on top of a 19% increase the year prior), overtaking tenancy deposit applications to become the third largest category

Chart 4: PRS tenants are more likely to experience the Tribunal as respondents than as applicants seeking redress

The 2023/24 Scottish Tribunals Annual Report breakdown of types of cases.

Source: Scottish Tribunals Annual Report 2023/2024

RentBetter Wave 3 shows that in 2024, only 33% of tenant participants were aware that PRS tenants could take cases to the Tribunal.[108] This indicated virtually no progress since 32% of Wave 1 participants in 2019 said they were aware of this five. While awareness amongst landlords (67%) and letting agents was much higher (95%), overall awareness had decreased from 78% to 68% since 2019. Tenants who had experienced the Tribunal did not find the process accessible, especially when they were operating without advice from a professional.

Applications to the Tribunal must be made in writing and can be made online. There are 49 different types of applications that can be made by either tenants or landlords, and the onus is on the applicant to determine what type of application form should be used. Each is listed with a link containing guidance on the topic, i.e. “Application for damages for unlawful eviction” or “application for determination of whether the landlord has failed to comply with the repairing standard”.[109] Applicants are encouraged to seek legal advice if their ground is not listed. In a number of cases, eligible applicants are able to apply for a legal aid grant to the Scottish Legal Aid Board to assist with the costs of seeking legal advice.[110] While the applications are clearly categorised and named, this process may be daunting for tenants to navigate. Decisions are made following a hearing, at which a tenant can opt to be represented.

RentBetter Wave 2 contains qualitative research including interviews with 16 tenants who had had disputes with their landlords, and 10 tenants whose disputes resulted in an experience with the Tribunal. In-depth interviews covered tenants’ awareness of their rights; propensity to use advice services; raising complaints without involving the Tribunal; impact of disputes on the relationship with the landlord; and Tribunal’s accessibility, fairness, user-friendliness, and efficacy.

All participants found that the Tribunal system was too formal, lengthy, not easily accessible, cumbersome, stressful, and inadequate to hold landlords to account. In this regard we note that the Tribunal has no role in carrying out enforcement of payment or eviction orders, which is the responsibility of the successful party. We are not currently aware what tenants believe could be changed about the Tribunal system in order to make it easier to navigate and more user-friendly.

According to the Tribunal’s latest available Summary of Work (2022/23), in 9 out of 10 tenancy deposit cases that were competent and not withdrawn, an order is granted in the tenant’s favour, resulting in the non-compliant landlord paying the tenant an average of 1.7 times the deposit.[111] The Scottish Association of Landlords has commented that this effective mechanism has encouraged landlords to ensure they pay the tenant’s deposit into an approved scheme within 30 working days.[112] We consider this a positive impact of tenants applying to the Tribunal.

Despite the Scottish House Condition Survey suggesting that 35% of PRS properties are below the Tolerable Standard and 60% of PRS properties would not meet the Scottish Housing Quality Standard if it applied, the Tribunal’s 2023/24 Annual Report found that only 6% of all applications received that year (297) concerned a failure to meet the Repairing Standard.[113] We do not have sufficient data to establish whether this relatively low percentage is due to prevalence, a lack of awareness of the Tribunal, or other potential barriers. Only 10 out of Scotland’s 32 Local Authorities had submitted third-party applications in 2022/23.[114] Although this was an increase on 7 the previous year, it suggests a disparity in how likely a PRS tenant is to receive assistance from their Local Authority in accessing the Tribunal based on where they live. An understanding of why this is the case may result in improved outcomes for consumers.

Scottish Public Services Ombudsman

SRS tenants may complain to the Scottish Public Service Ombudsman (SPSO), once they have exhausted a two stage complaints procedure with their RSL or Local Authority. For example, under the Right to Repair, SRS tenants can write to their social landlord who must respond within 5 working days. If the response does not resolve the issue, they can ask for reconsideration (a stage 2 complaint). Should this not lead to a satisfactory resolution, they can complain to the SPSO.[115]

Applications to the SPSO generally must be made in writing, including online; however, this does not have to be the case if the tenant is unable to do so. Tenants can also give third parties written permission to make the complaint on their behalf.

In 2022/23, the SPSO received 361 complaints about RSLs (10%) and 1,051 complaints about Local Authorities (30%).[116] With regard to RSLs, 75% of complaints were upheld. We note that Local Authority complaints include other matters than tenancy issues and as we have not accessed a breakdown of the number of complaints, we are unable to provide equivalent figures.

The SPSO regularly evaluates their work and has a number of policies and procedures relating to accessibility and consumers in vulnerable circumstances.[117] It also provides advice and support to organisations with regard to the application of policy and complaints handling. This guidance service is likely to result in improved services to tenants and may result in a need for fewer cases being escalated.

Other pathways available to tenants

Aside from the Tribunal, a few other resolution mechanisms exist for PRS tenants; but they apply to a limited number of tenants and circumstances:

- PRS tenants with a Private Residential Tenancy who wish to challenge what they consider to be an unduly high rent increase can apply to Rent Service Scotland (RSS).[118]

- PRS landlords and letting agents in Scotland have the option to join a redress scheme; however, this is not compulsory

- For certain disputes there is the option of Simple Procedure at the Sheriff Court.[119] This may be an option for tenants to seek an order to make a landlord carry out repairs if the Tribunal dismissed their case, or to recover owed sums with a maximum of £5,000 from their landlord

- There are three statutory tenancy deposit schemes in Scotland, which each offer an adjudication service specifically relating to deposits

- Mediation services

From 2018 to 2022, the University of Strathclyde Mediation Clinic conducted a project to promote early resolution within the housing sector, focussed on PRS disputes in particular. [120] The aim was to provide pro bono mediation for the private rented sector. The majority of cases came from the Sheriff Court and, while the First-Tier Tribunal (Housing and Property Chamber) may have been the end destination for some participants, no referrals were received from that source. Other housing advice and support services, despite expressing goodwill towards the service, also referred very few cases. Given its significant caseload from the Sheriff Court, the Clinic brought the housing project to a close and decided to focus on civil cases.

We were able to access the Final Report of the Strathclyde Housing Mediation Project, which notes that early intervention is key to increase the chances of mediation being successful.[121] It also suggests that the inability of the Tribunal to refer cases to a specific mediation service provider formed a “major barrier”, and that “more needs to be done to highlight the benefits of mediation to the sector”. This suggests that more work is required to increase understanding of the role of mediation and to promote smoother pathways if it is to be a more mainstream dispute resolution option.

Key learnings:

- The absence of a PRS regulator and higher costs associated with renting privately mean that renting privately tends to be more expensive, but with higher exposure to unresolved detriment than renting socially. Therefore, when tenants on low incomes consider that their only option is to enter the PRS, they may be exposed to factors that compound issues with their income or other vulnerabilities

- Evidence suggests an imbalance between the prevalence of issues PRS tenants experience and the use of redress mechanisms. While many are able to resolve any issues with their landlord or letting agent directly, evidence suggests that particularly tenants on low incomes or in vulnerable circumstances may choose not to raise disputes out of fear of how this may impact on this relationship, or on the security of their tenancy

- It would be beneficial to have a deeper understanding of how tenants can be made aware of and enabled to seek advice and support from organisations and officials who are there to assist and advise them.

- Publication of more granular data reflecting the realities of tenants’ experiences by the Scottish Government, landlords, the Tribunal and other relevant bodies, would be beneficial to establish how tenants are interacting with the system and where policy changes may be needed to achieve improved outcomes

4. Conclusions and Next Steps

We examined multiple sources from across the research, advice, regulatory, and dispute resolution landscape. This resulted in a comprehensive overview of the issues both private and social rented sector tenants are facing in Scotland, which can be used by those with an interest in housing policy to inform future research and advocacy activities.

Evidence suggests that many tenants are struggling to meet housing costs, as advertised rents in the PRS have risen sharply during the cost-of-living crisis and to a lesser extent in the SRS. While what is affordable to tenants remains undefined, the Scottish Government has tasked a working group of housing experts to reach a shared understanding, which may help improve outcomes for tenants when making policies.

Affordable PRS properties are increasingly important for lower-income groups due to the ongoing shortage of supply in socially rented housing. However, higher rents and deposits in the PRS can create barriers to access, and renters on low incomes unable to secure social housing due to limited availability might face compounding disadvantages. Further research is needed to determine how significant an issue this is.

There are differences in the quality of property and service that PRS, Local Authority, and RSL tenants are experiencing, which may be attributed to the presence of stricter housing standards and the presence of a dedicated regulator in the SRS. A tenure neutral standard might alleviate inequities, and the Scottish Government is exploring this. Evidence also suggests that the renting experience of RSL tenants is generally more favourable than that of Local Authority tenants. Further research would be required to chart contributing factors and what may be done to improve the latter.

In each of the three consumer issues we examined, our review identified a number of areas where the evidence base can be strengthened to help inform the development of evidence-based policies to address consumer needs and improve outcomes. For example, the existence of robust data on actual rents paid would have allowed for more accurate assessment of the necessity of a cap, or to evaluate its impact.

Our review shows some reluctance amongst tenants to raise issues they encounter in their tenancies. We consider that more evidence is required to understand how PRS tenants can be enabled to resolve issues relating to their tenancies, and what their experience is of using existing pathways. As Consumer Scotland seeks to increase consumer confidence and to reduce harm to consumers, in particular those on low income households or in vulnerable circumstances, we are well placed to add value through further research in this space.

To help bridge the gap that currently exists between the description of experiences and identifying ways to improve outcomes for tenants, Consumer Scotland is commissioning primary research to understand the experience of PRS tenants who experience issues relating to their home or tenancy, or disputes with their landlords. Based on the findings from this work, we intend to publish a paper setting out conclusions and recommendations in 2025.

5. Endnotes

[1] S6M-13197 | Scottish Parliament Website

[2] Housing Investment Taskforce - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[3] Private residential landlord and property statistics: FOI release - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[4] Scotland’s Census 2022 - Housing | Scotland's Census (scotlandscensus.gov.uk)

[5] The lower number of PRS households assessed in the Census than the landlord register may be attributed by the fact that Census data is largely reliant on returns by households. No returns were received from 1 in every 10 households, which is also likely to include properties that were empty at the time of fieldwork. To increase reliability, collected information from the Census was calibrated using estimation and adjustment; however, full accuracy cannot be insured.

[6] Annex A – Trends in the Size of the Private Rented Sector in Scotland - Private Sector Rent Statistics, Scotland, 2010 to 2022 - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[7] Consumer Scotland Act 2020 (legislation.gov.uk) and The Consumer Scotland Act 2020 (Relevant Public Authorities) Regulations 2024 (legislation.gov.uk)

[8] The Guidance | Consumer Scotland

[9] Regulatory Framework | Scottish Housing Regulator

[10] Housing (Scotland) Bill: Call for Views | Consumer Scotland

[11] Scottish Government consultation on Delivering net zero for Scotland's buildings - Heat in Buildings Bill | Consumer Scotland

[12] Scottish Government consultation on a Social housing net zero standard | Consumer Scotland

[13] Scottish Social Housing Charter November 2022 - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[14] Housing (Scotland) Act 2010 (legislation.gov.uk)

[15] Rent affordability in the affordable housing sector: literature review - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[16] https://blog.shelter.org.uk/what-is-affordable-housing/

[17] Defining and measuring housing affordability (nationwidefoundation.org.uk)

[18] Housing Affordability Working Group minutes: May 2024 - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[19] Housing affordability study: Findings report (www.gov.scot)

[20] 0362-rapid-rehousing-transition-plans-report-final.pdf (cih.org)

[21] Autumn Budget 2024 - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[22] How has the first six months of new legislation affected the market | ESPC

[23] Housing (Scotland) Bill as Introduced (parliament.scot)

[24] Setting the Table Guidance: Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[25] Minister for Housing: Statement on Housing (Scotland) Bill - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[26] new-deal-tenants-draft-strategy-consultation-paper.pdf (www.gov.scot)

[27] https://housingevidence.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Living_in_scotland_PRS_survey_report_sept_2022.pdf

[28] Housing challenges faced by low-income and other vulnerable privately renting households - UK Collaborative Centre For Housing Evidence

[29] Scottish Housing Market Review Q2 2024 - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[30] https://hub.rightmove.co.uk/content/uploads/2024/10/Rental-Trends-Tracker-Q3-2024-FINAL-1-1.pdf

[31] https://hub.rightmove.co.uk/content/uploads/2023/10/Rental-Trends-Tracker-Q3-2023-FINAL.pdf

[32] Scotland’s Economic and Fiscal Forecasts – December 2023 | Scottish Fiscal Commission Figures calculated from cells H172 - H174 of sheet 'Figure S.37' in the file 'Economy - Supplementary tables'.

[33] https://theses.gla.ac.uk/84408/3/2023WatsonPhD.pdf

[34] https://rentbetter.indigohousegroup.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/11/Tenant-survey-report-Wave-1-published.pdf

[35] 2023WatsonPhD.pdf (gla.ac.uk)

[36] Rental Market Report: September 2024 - Zoopla

[37] National Report on the Scottish Social Housing Charter - Headline Findings - 2023-2024 | Scottish Housing Regulator

[38] National Panel of Tenants and Service Users 2022 to 2023 | Scottish Housing Regulator

[39] Scottish House Condition Survey 2022 (www.gov.scot) Table 2.2 Mean EER and percentage in EPC bands ABC.

[40] sector-analysis-statistics-2022-23-fyfp-analysis-report-december-2022.pdf (housingregulator.gov.scot)

[41] Living in Scotland’s private rented sector: a bespoke survey of renter’s experiences - UK Collaborative Centre For Housing Evidence

[42] Housing Lists - Housing Statistics 2022 & 2023: Key Trends Summary - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[43] Housing Statistics for Scotland Quarterly Update: New Housebuilding and Affordable Housing Supply to end June 2024 - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[44] Homelessness in Scotland: 2023-24 - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[45] https://www.zoopla.co.uk/discover/property-news/rental-market-report/ and Rental Market Report: March 2024 - Zoopla

[46] Wave3-FINAL-Main-Report-AE090924-publication.pdf (indigohousegroup.com)

[47] https://www.cih.org/media/szslk3vv/0362-rapid-rehousing-transition-plans-report-final.pdf

[48] https://www.rettie.co.uk/property-research-services/assessment-of-scotlands-rent-freeze-and-impacts

[49] https://scottishlandlords.com/news-and-campaigns/news/crunching-the-numbers/

[50] https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/corporate-report/2023/06/cost-living-tenant-protection-scotland-act-2022-2nd-proposed-extension-statement-reasons/documents/2nd-proposed-extension-cost-living-tenant-protection-scotland-act-2022-statement-reasons/2nd-proposed-extension-cost-living-tenant-protection-scotland-act-2022-statement-reasons/govscot%3Adocument/2nd-proposed-extension-cost-living-tenant-protection-scotland-act-2022-statement-reasons.pdf

[51] About - Scottish Landlord Register (landlordregistrationscotland.gov.uk)

[52] consumer-scotland-consultation-response-to-housing-bill-call-for-views.pdf

[53] The Housing (Scotland) Act 2014 defines letting agency work as things done by a person in the course of that person's business in response to relevant instructions which are a) carried out with a view to a landlord who is a relevant person entering into, or seeking to enter into a lease or occupancy arrangement by virtue of which an unconnected person may use the landlord's house as a dwelling, or b) for the purpose of managing a house (including in particular collecting rent, inspecting the house and making arrangements for the repair, maintenance, improvement or insurance).

[54] Home - Scottish Letting Agent Register (lettingagentregistration.gov.scot)

[55] Letting agent code of practice - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[56] Regulating the sector - Private renting - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)