1. Who we are

Consumer Scotland is the statutory body for consumers in Scotland. Established by the Consumer Scotland Act 2020, we are accountable to the Scottish Parliament. The Act provides a definition of consumers which includes individual consumers and small businesses that purchase, use or receive products or services.

Our purpose is to improve outcomes for current and future consumers and our strategic objectives are:

- to enhance understanding and awareness of consumer issues by strengthening the evidence base

- to serve the needs and aspirations of current and future consumers by inspiring and influencing the public, private and third sectors

- to enable the active participation of consumers in a fairer economy by improving access to information and support

We work across the private, public and third sectors and have a particular focus on three consumer challenges: affordability, climate change mitigation and adaptation, and consumers in vulnerable circumstances.

2. Overview

In a market as fundamental to the success of the economy and the wellbeing of citizens as the retail energy market in Great Britain, the importance of safeguards to maximise benefits and mitigate risks for consumer interests must be integral to any programme of work, including interventions aiming to enhance affordability and tackle the energy debt burden. As such, we consider that consumer interests should be placed at the centre of this process, and suggest this is achieved by:

- Reviewing policy options against the Consumer Principles,[i] to provide a framework to enable the development of more consumer-focused policy and practice, and ultimately the delivery of better consumer outcomes

- Setting out a clear articulation of intended consumer outcomes, including a distributional analysis of the socio-economic impact of any reforms which are then tested against a range of different consumer archetypes

In its Call for Input,[ii] Ofgem recognises the negative implications of energy debt to both consumer welfare and the retail market’s ability to function effectively. Self-rationing to afford energy debt repayments is cited as a particular concern, due to the associated harms of living in a cold, damp home, whilst squeezed liquidity and supplier margins, and the impact on competition and the ability to innovate, could impact the future energy market and delivery of net zero.

Consumer Scotland regularly surveys households in Scotland on their perceptions of energy affordability. Our most recent Tracker,[iii] which surveyed 1,609 domestic consumers in Scotland in February 2024, reported an improving picture as regards respondents’ overall perception of energy affordability. The number of households reporting difficulty keeping up with energy bills had fallen since the Winter 2022-23 wave of the survey, which is consistent with falling energy prices in that period, and lower than at any point since the survey started in Spring 2022. This is welcome news, but has to be understood within the context of rising energy debt in the GB market, which Ofgem reports now stands at over £3bn – a record level[iv]. In regards to perceptions of energy debt, our most recent Tracker found that:

- More than one in twelve (9%) of households in Scotland are in energy debt: when accounting for a broad definition of debt accrued to pay for energy (including those who have borrowed from family/friends or taken out loans to pay their bills, as well as those in arrears with their supplier). Using this broader definition of debt demonstrates that the issue is wider than currently defined within the energy market and implies that energy debt in GB households likely exceeds Ofgem’s latest quoted figures for energy debt and arrears owed to energy suppliers of over £3bn

- Of those who told us they were in energy debt, around 15% told us they faced debt recovery action. Looking ahead, forty-eight percent of consumers in energy debt are not confident that they will be able to clear that debt

Consumer Scotland has previously recommended targeted energy bill support[v] during periods of heightened financial pressure on households, and we consider that this should be a feature of the energy affordability landscape moving forward. This is likely to require action from UK Government, with support from Ofgem, to improve affordability amongst those struggling to pay for their ongoing energy consumption, and to prevent the negative consequences of energy debt.

3. Responses

Q1: What are the key drivers of energy affordability challenges and how do we expect those to change in the future?

Energy is an essential-for-life service which creates significant impacts on consumers if they are unable to afford their bills. Energy affordability challenges and debt are creating ongoing challenges for consumers. Our latest Energy Affordability Tracker has found that, although there is improvement in the perceived affordability of energy bills, there is concern amongst some consumers about their ability to clear debt.

Energy affordability is a dynamic state which is driven by multiple factors related to ability to pay and cost

Consumer Scotland’s approach to assessing domestic energy affordability is to understand this as a dynamic sliding scale, not a static state. As such, energy is not simply 'affordable' or 'unaffordable', but rather a household has a varying level of energy affordability at any given time which is dependent on a number of variable factors, or 'drivers', the balance of which are unique to that household. In responding to this Call for Input we have categorised these drivers into two main groupings: 'ability to pay' and 'cost'. Each of these groupings is dynamic and the affordability of energy responds to changes in either set of factors. We have included the following aspects within the two groupings:

Ability to pay consists of, but is not limited to:

- the household's income,

- its competing expenditures (essentials),

- and financial support (eligibility for)

Cost consists of, but is not limited to:

- the price of energy,

- the energy efficiency of the dwelling,

- levels of consumption (i.e. determined by energy need)

The constant interplay between these two groupings of drivers determines a household's position on the energy affordability scale at any given time. The drivers of energy affordability are not unique to this concept; there is, for example, some consistency with the four recognised drivers of fuel poverty which form part of Scotland's fuel poverty legislation. These are: low net adjusted household incomes, high household fuel prices, homes having low levels of energy efficiency, and the inefficient use of fuels in homes. In the Scottish legislation, a household is defined as being in fuel poverty if its necessary fuel costs exceed a proportion of its income (10%) and if its remaining income (with deductions for essential costs) is insufficient to achieve a reasonable standard of living (less than 90% of its Minimum Income Standard).[vi]

High essential energy expenditure is often an overlooked component of energy affordability and can create and exacerbate affordability challenges

High essential energy expenditure can be defined as the expenditure required for consumers to meet their basic needs, which are determined by factors beyond their control. These high essential costs can increase energy costs to the extent that energy bills are regularly unaffordable, even if a household is considered high income. By the same reasoning, a low income household which also has high essential energy expenditure is more likely to experience significant challenges in affording its energy costs.

There are multiple reasons that may result in people facing high essential energy expenditure but some common drivers are:

- Low levels of energy efficiency[vii][viii]

- Disability-related energy costs[ix][x]

- Reliance on traditional forms of electric heating (given the high running costs)[xi]

- Caring responsibilities

Consumer Scotland’s recent reports Disabled consumers and energy costs – interim findings and Impacts of energy costs on people who are disabled or living with health conditions provide more detailed information on disability-related costs.

Case study on disability and energy affordability

Consumer Scotland is undertaking ongoing work to understand the experience of disabled energy consumers. The work has highlighted the significant impact that high essential energy expenditure can have for certain groups of disabled consumers. These impacts are not always fully recognised or understood by policymakers and there appears to be insufficient support currently available to consumers to ameliorate these challenges.

Consumer Scotland’s recent research with disabled consumers (‘experts by experience’) and organisations representing disabled people and those with health conditions found that some disabled people face specific affordability challenges which arise from three interlinked drivers:

- High essential energy cost (as above)

- Lower income and higher cost of living

- Limited opportunity to reduce energy consumption without detriment

This qualitative research also highlighted that these drivers intersect with demographic factors such as race and age, and with energy-related factors such as heating type (e.g., traditional electric heating) and payment method (e.g., prepayment).

In the context of disability, high essential energy usage which is necessary to meet the needs that are essential to the health and wellbeing of the individual(s) and their household. For some disabled people, this may encompass costs which do not apply to non-disabled people including (but not limited to):

- Medical equipment (e.g., oxygen concentrators, at home dialysis, hoists, hospice beds)

- Mobility equipment (e.g., electric wheelchairs, scooters)

- Essential care needs (e.g., increased washing needs, increased bathing needs, cost of carers in home such as heating requirements)

- Safe heating regimes (e.g, enhanced heating regime or more) which includes the need for heat to manage medical conditions including pain, respiratory risk, fatigue, but also comfort

Disabled people are not a homogenous group and have very different needs and incomes. Our analysis of the Scottish Household Survey suggests that it is disabled people with conditions that limit them a lot who are disproportionately struggling with energy costs (see section 2.4.)

Debt is a driver of energy affordability challenges and a symptom

Debt can be both a symptom and a driver of energy affordability challenges. This is because debt is often accrued as a result of consumers being unable to afford their ongoing consumption, and is then repaid in addition to this ongoing consumption, thereby compounding the existing difficulty.

Energy debt can manifest in a number of ways, but we consider there to be two main types:

- direct energy debt, i.e. debt or arrears owed by a consumer to the supplier, and

- indirect energy debt, which may be debt that consumers have accrued on credit cards, by borrowing from friends or family, or by missing rent or mortgage payments to afford energy bills. When energy debt is understood in these terms, the aggregate debt burden experienced by consumers is likely to be higher than the reported £3.1bn within the retail energy market[xii]

Consumer Scotland’s research, which draws on data pooled across our Autumn 2023 and Winter 2023-24 Energy Affordability Tracker survey waves, has highlighted the following issues as different dimensions of debt that may impact on affordability:

Payment method

The payment method that consumers use for their energy was associated with the type and level of energy debt that households reported experiencing. Certain payment methods are more likely to be associated with ‘hidden debt’ (for example credit card debt or borrowing money from a friend or family member) which may not be considered when suppliers are assessing ability to pay and calculating repayment plans. For example, prepayment customers are more likely to report owing money to someone in order to cover their energy costs[xiii].

Demographic

Consumer Scotland’s recent analysis of our Energy Affordability Tracker survey data found that disability, having young children and low income, are most associated with energy indebtedness. Low income is an expected risk factor for energy debt, but it is important to note that there are other characteristics of consumer groups which may increase their risk of energy debt. There is a need for policymakers to set out a clear articulation of intended consumer outcomes, supported by a distribution analysis of the socio-economic impact of any proposed reforms to ensure that they are appropriately designed.

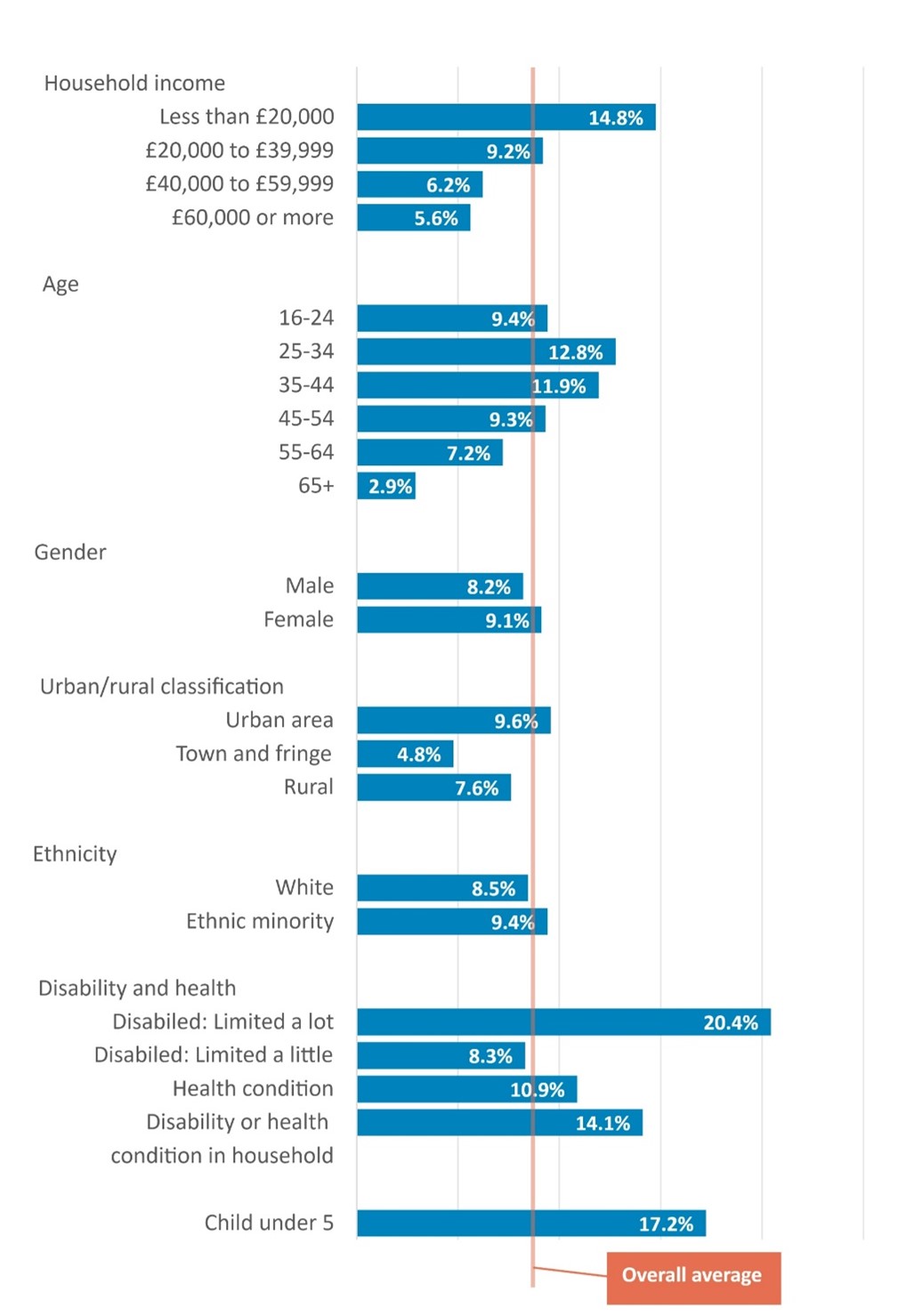

Chart 1: Disability, having young children and low income are most associated with energy indebtedness

Source: Consumer Scotland analysis of our Energy Affordability Tracker: Are you in energy debt or arrears? By this we mean behind on energy bill payments, repaying debt to your energy supplier, paying debt recovery through a prepayment meter, or owing money to someone else as result of borrowing money to pay for energy costs. Analysis by selected demographic characteristics.

Whilst it is important to consider the inter-relationships between income and other characteristics, Consumer Scotland has also controlled for other factors that might increase energy affordability challenges in order to identify the particular contribution that any of these characteristics makes to the likelihood of a household experiencing energy debt. Our analysis shows that:

Having a household income under £40,000 a year is associated with an increased probability of energy debt. Households whose income is less than £20,000 a year are 5% more likely to be in energy debt than a household with an income of over £60,000 when controlling for other variables

The association between age and energy debt is not statistically significant when controlling for other factors such as age, income or dwelling type

The strongest association with energy debt comes from having a child under 5 in the household (10% more likely), having a disability that limits them a lot (8% more likely) and having a health condition (3% more likely)

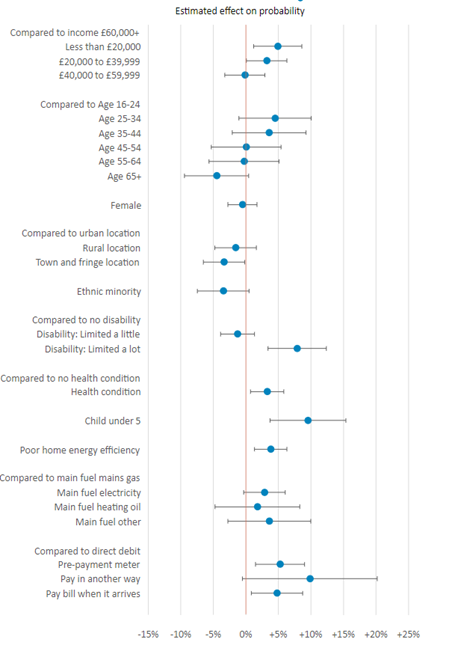

As per Chart 2, consumers living in properties with poor levels of energy efficiency (self-assessed), as well as those who pay by prepayment meter or on receipt of bill, are statistically more likely to be in debt

Chart 2: Disability, ill health, poor energy efficiency and young children are associated with higher risks of energy debt

Source: Consumer Scotland analysis of our Energy Affordability Tracker: Are you in energy debt or arrears? By this we mean behind on energy bill payment, repaying debt to your energy supplier, paying debt recovery through a prepayment meter, or owing money to someone else as a result of borrowing money to pay for energy costs. Logistic regression analysis.

The original report, Insights from the latest Energy Affordability tracker: causes and impact of energy debt, provides more in-depth analysis on the points set out here.

Changes to energy affordability challenges in the future

Consumers experience unequal outcomes in the energy market at present and there is a risk that these disparities are translated into or exacerbated by future market reform, unless action is taken to address these matters.

Consumer Scotland is concerned that the costs of achieving net zero targets should be proportionate and fair for all consumers. Barriers due to access, appropriateness or personal circumstances could prevent some consumers obtaining the benefits arising from the transition; some of these barriers may be caused by prohibitive upfront costs, unsuitable pricing structures or expensive running costs. For example, the shift towards rewarding greater flexibility of energy usage away from peak times may create inequalities between those who are able to flex their energy use and those who cannot, due to disability, care needs or other barriers[14].

Not all consumers can access or obtain the benefits/savings associated with flexible time of use tariffs. For example, someone reliant on using medical equipment, or who has caring needs, may need to access energy at set times of the day and will therefore struggle to reduce their demand at peak times. Whilst unlocking flexibility provides opportunities for greater consumer choice, incentivises the uptake of low-carbon technologies and improves cost-effectiveness, there are still barriers - particularly for consumers in vulnerable circumstances.

Heat networks are scheduled to become a regulated industry in April 2025. Consumer Scotland will be the statutory advocate for heat network consumers in Scotland. We would like to take the opportunity to highlight that there is a need to ensure that any work done on affordability and debt is applicable to heat networks but may also need to be tailored to ensure it is fully applicable in that context. There has already been instances of billing and debt issues for consumers on heat networks which have exacerbated affordability challenges[15].

Looking ahead, there is an opportunity to reconsider how the energy industry’s approach to design can most effectively meet the needs of all consumers. The future market should be designed in a way that ensures the inequalities in the current energy market are addressed. The objective should be to achieve a fair, inclusive energy market which reduces inequalities of outcome across consumers groups, whilst enhancing affordability for all.

Q2: What options should be explored to tackle energy affordability?

On the basis of available evidence, Consumer Scotland recommends that there is a need for targeted energy support for specific groups

It is clear that a combination of persistent high prices and high essential energy expenditure has left certain groups of consumers more exposed, with particularly acute impacts on their financial resilience, health and wellbeing, as well as wider economic impacts, including for example, on energy debt and healthcare systems[16].

Consumer Scotland recommends that the UK Government should explore a range of options for providing targeted bill support. These options should consider who is targeted (the criteria), how they are targeted (the mechanism) and how much support eligible consumers should receive. For each option, analysis should include an assessment of the comprehensiveness of the delivery mechanism, i.e. what proportion of those consumers identified as being in need of support would be provided with this support; whether the support can be delivered automatically or whether consumers would be required to apply; and what the administrative costs would be for suppliers and other organisations to implement.

Low income consumers and those with high essential energy expenditure (such as disabled consumers) should be priority groups for targeted support interventions

Based on our evidence, and feedback from our stakeholders, Consumer Scotland recommends that any targeted support intervention should pay particular attention to the specific needs of consumers with high essential energy expenditure. The rationale for this is outlined in question 1 and 2.4 of this section. With regards to disabled consumers, our research shows specifically higher energy needs, affordability challenges and risk of debt for those who are limited a lot by their disability.

If an affordability policy was targeted only on the basis of financial means (e.g. income), without any consideration of energy need, then this would implicitly provide the same level of financial support to households that had similar incomes but potentially very different energy needs. For example, a household with energy use which is several times higher than average due to running medical equipment, and charging mobility equipment, is likely to struggle even if they are not on a low income.

Future targeting of support should include disabled people who have high essential energy needs. Whilst there are complications to determining which consumers may fall into this category, consideration should include needs which may be hidden, such as enhanced personal care or increased lighting for blind and visually impaired people. Whilst there may be an income-related component, there may be a number of consumers with high essential energy needs who are not classed as low income. Therefore, more consideration needs to be given to encompassing affordability challenges driven by these high need as well as low income.

Other groups of consumers with high essential energy needs (and therefore high expenditure) may include those who live in properties with poor energy efficiency, or those reliant on traditional forms of electric heating. There is likely some intersection between these groups and consumers on low income and disabled consumers. There is a need to consider how these consumers can be best supported to protect them from excessively high bills due to property characteristics and heating type.

There are multiple considerations when it comes to implementation of targeted energy bill support

As set out above, Consumer Scotland has recommended that consumers with high essential energy expenditure should be amongst the key groups that are targeted for energy bill support. In designing targeted support interventions aimed at these groups, there are a variety of data sources which could be used to identify potentially eligible households. Eligibility criteria based on social security benefit receipt will inevitably leave some gaps in support because many low income households are not in receipt of benefits. There are significant support schemes that work automatically but it is important that there is also a safety net of additional approaches, e.g. referral routes, to capture the likely large number of households who might need support but who do not receive the relevant qualifying (passport) benefits.

Table 1 outlines potential sources of data which may be used to support delivery of targeted energy support. Note that this table is not exhaustive and the purpose is to identify potential sources of data which may be used and to identify any constraints

|

Data type |

Data options |

|

Benefits data |

The use of passported benefits is the most common current approach (for example, Universal Credit, Employment and Support Allowance and Job Seeker’s Allowance). However, a large proportion of low-income households don’t receive means-tested benefits, so there is a need to consider additional alternative data or referral routes for support. |

|

Energy use data |

The Valuations Office data (as used for Warm Home Discount) does not exist in Scotland – therefore alternative proxies for energy use are needed although there are not clear equivalent data sets. |

|

Disability data |

The most straightforward approach to targeting support for disabled consumers is to match with disability benefits such as Adult Disability Payment (known as Personal Independence Payment in England and Wales). These are also tiered depending on level of support needed which may be valuable in reaching those consumers limited a lot by their disability[17]. However, this does not account for energy need, so there is a need to explore data matching against available Scottish data sets. |

|

Other income data |

There is a data gap in identifying households with low incomes who are not in receipt of benefits. One option to address this barrier is an additional referrals mechanism, to sit alongside passporting processes. This could be application-based on specific criteria or referrals through a trusted third party. Another option may be to explore whether any existing datasets could help enable targeted interventions. For example, Citizens Advice proposed the use of HMRC data to identify income for energy bill support, although there are challenges to merging household income data[18]. |

There is potential for data-matching which can make use of multiple sets of data through an automatic process to identify recipients. Data-matching reduces the burden on both consumers (reducing the need for onerous application-based approaches and awareness raising) and suppliers (the costs of administering the scheme). However, there are multiple barriers that need to be overcome in order to get the full benefit of data-matching.

Scotland faces specific challenges around data-matching which also need to be overcome in order to ensure parity of scheme design for any future targeted energy support. Consumer Scotland is aware of multiple proposals for the enhancement or expansion of Warm Home Discount as a vehicle for targeted bill support[19][20][21]. Whilst we would broadly support the use of existing structures and mechanisms for distributing support, the Warm Home Discount in Scotland still retains an applications process for its Broader Group (see the box below). Further challenges for data-matching include the wider devolution of certain social security benefits, notably those associated with disability and caring. For example, data-matching with benefits administered through Social Security Scotland would require agreement, and data compatibility, with an additional agency – potentially adding further complexity.

There is a need to include consumers with high essential energy expenditure as a separate, additional group when considering affordability support

As outlined in question one, high essential energy expenditure can be defined as: the expenditure required for consumers to meet their basic needs, which are determined by factors beyond their control. This could include poor energy efficiency, energy costs related to disability, reliance on traditional forms of electric heating or caring responsibilities.

Consumer Scotland’s evidence indicates that a significant number of disabled people, particularly those with limiting conditions, face additional high essential energy costs[22]. These costs need to be met to avoid consumers experiencing harm to their health and wellbeing. As our analysis suggests, affordability challenges are particularly acute for those limited a lot by their disability, and there is a strong case for focusing support on those with the highest energy needs (and who may also be on lower incomes).

For example, Marie Curie (2023) found that people with some terminal illness may see their energy bills go up by as much as 75% after they are diagnosed[23]. Similarly, Scope (2023) calculated that on average disabled people spent a greater amount of their budget on energy compared with a non-disabled people – amounting to £634 over a year[24].

As we have outlined above, there is evidence supporting the case for the inclusion of disabled people within any affordability support. Ideally, support would target those with high energy needs but particularly where that intersects with low ability to pay (which may not correlate perfectly with low income). However, there are practical challenges with being able to identify and effectively target this group given the complexity of data required. For example, data matching between Adult Disability Payment/Personal Independence Payment and income-related benefits would be ineffective assuming (a) benefits data was already used to target low income groups (b) the intention is to capture low ability to pay rather than low income.

Furthermore, older people and households with young children are likely to have high essential energy expenditure due to the high risk of illness and wellbeing impacts from living in cold homes. Public Health Scotland (2022) have recently conducted a rapid assessment of population health impacts from the rising costs of living. As part of the work, they highlight that fuel poverty and cold homes contribute to excess winter mortality[25]. Our Energy Affordability Tracker particularly points to increased affordability challenges for those with children under 5. The British Medical Journal (2022) published evidence that strongly suggests that growing up in poor homes has a direct and severe impact on health. This includes the risks of cold, damp and mouldy homes which mean higher than average rates of respiratory infections, asthma and other forms of ill health and disability, as well as increased mental health issues, impacts on growth and cognitive issues[26].

Q3: What factors should be considered when redistributing costs?

Consumer Scotland recognises that there is a challenge in how to distribute costs (including cross-subsidy) in a way that is fair. For example, when considering fairness in relation to the recovery of fixed costs in the energy system (i.e. through standing charges), we highlighted that isolated interventions would likely shift costs towards high volume users such as disabled consumers and households with young children[27][28]. Similarly, other potential interventions are likely to require similar assessments of any potential unintended consequences to ensure that affordability challenges are not created, or exacerbated, for any groups of consumers as a result of shifting the distribution of costs between different groups.

We also recognise Ofgem’s limitations in scope regarding how costs are distributed between different groups of consumers. We welcome Ofgem’s levelisation policy aims and the move away from consumer impacting cost-reflectivity (i.e., prepayment meters or standard credit/customers who pay on receipt of bill) especially given the known higher risks of affordability challenges for these payment methods.

A principles-based approach may support work in ensuring ongoing fairness when considering cost redistribution. For example, the broader cost issue could be considered in two stages:

- First, determine the principles by which system costs should be shared across consumers, and use these principles as the basis on which to consider cost redistribution between consumer groups. Ofgem already does this, for example through its Targeted Charging Review (TCR)[29]

- Second, design and implement appropriate energy affordability policies that protect consumers who most need support with their bills. Much of this role sits with Government[30]

Q4: To what extent is debt a factor that puts suppliers off taking on new customers or offering certain types of services and tariffs to them?

Not answered

Q5: With reference to the themes and indicators in our Competition Framework, to what extent is the affordability of energy and the build-up of legacy debt affecting competition and innovation (including new entry) in the domestic retail market?

Not answered

Q6: What represents best practice in debt management by suppliers?

In March 2024, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), Ofgem, Ofwat and Ofcom published a joint debt collection statement via the UK Regulators’ Network[31]. The statement identified that customers subject to collections activity are highly likely to be in vulnerable circumstances due to financial difficulty, such as problems with their physical or mental health; that firms should be aware that customers in vulnerable circumstances may find it difficult to engage with creditors; and that customer vulnerabilities may be exacerbated if creditors take an inappropriate approach to collections.

Drawing on rules, guidance and best practice from the individual sectors, as well as a joint agreement which set out shared expectations on how firms should support customers in financial difficulty, the regulators set out four outcomes that they expect firms to deliver in relation to debt collection:

- Firms ensure an appropriate frequency of collections communications and reduce the frequency where it is not delivering positive customer engagement or is causing harm to consumers

- Collections communications use tone that is supportive

- Information about free debt advice and how to access it is clear and prominent in collections communications, and that ‘warm’ referrals (where a firm directly refers a customer to another organisation) are used where appropriate

- Firms make it as easy as possible for advisers from free debt advice organisations to contact creditors

Consumer Scotland welcomes this cross-sector approach to driving up standards on debt recovery. In our response to Ofgem’s statutory consultation on consumer standards[32], in relation to debt intervention proposals such as the tactical use of payment holidays for those experiencing short-term financial stress, and the new contact ease guidance for suppliers, we argued that such initiatives are only as robust as their compliance monitoring and evaluation processes. It is encouraging therefore, that the four signatories of the joint statement have committed to monitoring how firms are supporting customers in 2024, and to take action where firms are falling short and delivering poor outcomes.

In the same response, acting on evidence from a stakeholder in the debt advice sector, we highlighted that consumers must be allowed to choose who advocates on their behalf in debt correspondence, and that this wish is respected by suppliers. We therefore welcomed the Energy UK Winter 2023 Voluntary Debt Commitment[33], which committed signatories to fully consider information (including budgets, affordable payment offers and prepared Standard Financial Statements[34]) and third-party authority forms, from a customer’s chosen credible debt or consumer body organisations, including FCA-authorised debt advisors. Consumer Scotland would like to see this commitment made permanent, as part of an appropriate framework or industry process.

Q7: What lessons can we learn from other sectors and countries on managing affordability and debt? And how should they be applied to the energy sector?

Consumer Scotland has been undertaking work to examine affordability interventions across different markets. The markets included within the analysis are broadband, gas and electricity, post and water. This is work is ongoing but we have highlighted emerging key learnings here for the benefit of the Call for Input:

- Most affordability interventions have points of friction or a lack of clarity for consumers. Issues around eligibility, application processes and different supplier approaches, alongside having to apply across multiple utility systems can have a negative impact on consumer outcomes. Within the context of the energy market, this may point to a need an improved consumer journey through designing energy bill support which has universal eligibility, if delivered through suppliers, and clear mechanisms to distribute support.

- The cost of living crisis alongside the investment required to meet net zero targets creates tensions when designing affordability interventions. Any intervention which requires cross-subsidy amongst consumers will present challenges in this context.

- Within the context of energy, this may include considerations of distributional analysis and of fairness when distributing costs of necessary investments between different consumers

- Automated payments and data matching removes barriers created by application processes when designing affordability interventions. There is a need to look at what other, market-level data may be relevant and necessary to identify and reach the consumer groups that require support. Within the energy market, this likely points to a need for support which is automatically targeted and delivered alongside an additional referrals process, if gaps are identified.

4. Endnotes

[1] Consumer Scotland (2024) A summary of Consumer Scotland’s Consumer Principles in the context of the future retail market in response to Ofgem’s discussion paper on the future of domestic price protection

[2] Ofgem (2024) Affordability and debt in the domestic retail market – a Call for Input

[3] Consumer Scotland (2024) Insights from latest Energy Affordability Tracker: Causes and impacts of energy debt

[4] Debt and Arrears Indicators | Ofgem

[5] Consumer Scotland (2023) Letter to the Chancellor ahead of the Autumn Statement

[6] Scottish Parliament (2019) Fuel Poverty (Targets, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Act 2019

[7] Scottish Government (2021) Tackling fuel poverty in Scotland: a strategic approach

[8] Office of National Statistics (2023) How fuel poverty is measured in the UK

[9] Consumer Scotland (2024) Disabled consumers and energy costs - interim findings

[10] Scope (2023) Extra burden of energy among disabled households

[11] CAS (2018) Hard wired problems: delivering effective support to households with electric heating

[12] Ofgem (2024) Welcome fall in the price cap but high debt levels remain

[13] Consumer Scotland (2024) Insights from latest Energy Affordability Tracker: Causes and impact of energy debt

[14] Citizens Advice (2023) A flexible future: Extending the benefits of energy flexibility to more households

[15] Glasgow Times (2019) MSP wants Ofgem to probe SSE Wyndford heating disconnections | Glasgow Times

[16] Consumer Scotland (2024) Insights from latest Energy Affordability Tracker: Causes and impact of energy debt

[17] Mygov.scot (2023) Adult Disability Payment

[18] Citizens Advice (2023) Social tariff now essential in era of high energy bills

[19] Citizens Advice (2023) Winter Warning: The urgent case for energy bill support this winter

[20] Citizens Advice (2023) Fairer, warmer, cheaper: new energy bill support policies to support British households in an age of high prices

[21] Social Market Foundation (2024) Fixing the roof while the sun shines: Improving energy bill support for the coming winter

[22] Consumer Scotland (2024) Collaborate research: impacts of energy costs on disabled people and those with health conditions

[23] k406-povertyenergyreport-finalversion.pdf (mariecurie.org.uk)

[24] Scope (2023) Extra burden of energy among disabled households

[25] Public Health Scotland (2022) Population health impacts of the rising cost of living in Scotland - A rapid health impact assessment

[26] BMJ (2022) Fuel poverty is intimately linked to poor health

[27] Consumer Scotland (2024) Response to the ESNZ Committee inquiry on fairness of customer energy bills

[28] Consumer Scotland (2024) Ofgem Call for Input on standing charges | Consumer Scotland

[29] Ofgem (2019) Targeted Charging Review: Decision and Impact Assessment

[30] Consumer Scotland (2024) Response to the ESNZ Committee inquiry on fairness of customer energy bills (HTML) | Consumer Scotland

[31] UKRN (2024) Joint Debt Collection Statement

[32] Consumer Scotland (2023) Response to Ofgem’s statutory consultation on consumer standards

[33] Energy UK (2023) Winter 2023 Voluntary Debt Commitment

[34] Known as the Common Financial Tool in Scotland