1. Executive Summary

Context and research objectives

Consumer Scotland is a Non-Ministerial Office that came into existence in April 2022 following passage of the Consumer Scotland Act 2020. It exists to advocate on behalf of all consumers in Scotland and to represent consumers’ interests. It receives specific levy funding to advocate for consumers in the water sector in Scotland as part of this. How water and wastewater services can contribute to a just transition to net zero, and how these services should be adapted to mitigate the impacts of climate change, are key issues that Consumer Scotland is focusing on.

In 2023 Consumer Scotland commissioned Ipsos to deliver a major programme of deliberative research to provide insight into how domestic consumers can and should be part of Scotland’s transition to a more resilient and sustainable water sector. The research focused on three key areas: household water use and disposal; water sector wastewater management (as it relates to the water environment); and surface (rain) water management.

The research sought to:

- Find out the extent to which consumers are aware of climate change impacts in the Scottish water sector and whether they understand the need for adaptation;

- Consider what information is needed and in what format to support informed consumer decisions;

- Understand consumers’ views on a range of policy options and solutions relating to water resources and services, sewerage and drainage;

- Explore consumers’ views on where responsibility should lie for tackling the impacts of climate change on water in Scotland, how urgently this needs to be done and what considerations should be taken into account;

- Seek to understand the motivations, the opportunities and the support required by consumers to change their water behaviours to be more sustainable;

- Use a deliberative approach to allow consumers to be presented with information and options and to consider their responses.

Research approach

A deliberative approach was chosen for this research due to the complex and multi-faceted nature of the topic. The specific methodology used was a public dialogue, whereby members of the public interact with specialists, stakeholders and policy makers to deliberate on issues relevant to future policy decisions.

Forty-one people from across Scotland took part over five three-hour online workshops between October and November 2023, to answer the following question: “How should we deal with the impacts that climate change is having - and will have - on water in Scotland?” Discussions were facilitated by moderators from Ipsos, and a range of specialists from across the Scottish water sector presented information at the meetings to inform participants’ deliberation. Between sessions, participants also engaged in an online community, which provided activities, information, an artist’s summary of the previous workshop discussions, and a forum for further discussion.

Key points: cross-cutting themes

- Most participants felt they knew little or nothing about the impacts of climate change on water or wastewater services prior to taking part in the research, although there was more awareness of issues with drainage and surface water flooding. When consumers learnt more about climate change impacts they were alarmed by the scale of the challenges.

- On learning more, participants saw a clear and urgent need for climate adaptation in the water sector. They expressed a desire for the sector to put long-term solutions in place and invest in innovative approaches.

- Affordability was a key theme raised by participants throughout. While there was acknowledgement that price rises to pay for improving Scotland’s water or wastewater infrastructure are likely to be inevitable, participants wanted reassurance that any investments would be ‘future-proof’ and provide value for money in the long term. A strong theme was that any negative impacts of this on consumers who can least afford to pay should be avoided.

- Aside from investing in infrastructure, there was a widespread belief that behaviour change from consumers and businesses would be an important factor in tackling the impacts of climate change on Scotland’s water resources, sewerage and drainage systems. It was felt there would be a broad openness among the public to doing things differently with appropriate support. However, participants also recognised change is likely to be challenging, as some consumers may be less willing or able to change.

- By the end of the dialogue, participants felt that everyone has a role in tackling the impacts of climate change on Scotland’s water sector: Scottish Government, Scottish Water, businesses, local authorities, people and communities. Education and raising awareness were consistently highlighted as important factors in empowering all consumers to do things differently.

Key points: water services and resources

- At the beginning of the dialogue, participants had limited knowledge of how water services worked in Scotland, but generally had positive associations. Participants were alarmed to learn about the potential water deficit that Scotland would face by 2050 and the risk to customers of a water shortfall.

- Participants’ reactions to the five Scottish Government policy ideas presented to them were underpinned by a strong sense of urgency, and they expressed a sense of frustration that these were not already in place. These policy ideas to help tackle the challenges ahead included a new Water Efficiency Strategy, national water resource planning and more stringent standards for water saving.

- There was an expectation that dealing with the impacts of climate change on water would require both action to reduce household and business water use and additional investment in building and upgrading infrastructure. However, participants felt that behaviour change would be able to happen more quickly, while infrastructure investment would take longer to be put in place.

- Participants felt that there would need to be guidance and support to help individuals make changes to their water behaviours, including education and awareness-raising about the need to reduce water usage, guidance to help people make the necessary changes and harnessing technology to improve monitoring. There were mixed views on the potential for water meters being installed and concerns about this being linked to billing.

- There was initial surprise at the age of Scotland’s water infrastructure. Participants were not typically in favour of new infrastructure-heavy solutions to tackle Scotland’s water shortfall, such as new dams or pipelines, due to concerns about costs and negative environmental impacts. Instead, there was a preference for updating existing infrastructure and more localised solutions, such as mechanisms to increase rainfall capture and utilise greywater.

- Participants generally felt that there should be a shared responsibility for tackling the impacts of climate change on water in Scotland, including Scottish Government, Scottish Water, businesses, local authorities, communities and individuals. Scottish Government was seen to have a particularly important role to play, by taking the lead and coordinating initiatives, setting strategy and targets, ensuring regulation and incentivising different actors to make changes.

Key points: wastewater services

- Participants had typically not thought about the sewerage system previously, although those who had experienced using a septic tank were familiar with how this worked. Upon learning more from the expert presentations, there was surprise that rainwater goes into the same place as sewage. There was concern about the impact of overflows (CSOs) into the sea, and the effect that increased rainfall will have on this.

- While participants acknowledged that changing the entire wastewater system may not be practical, they generally felt that more should be done to improve the system and reduce the likelihood of CSOs. Participants also thought there should be a robust long-term strategy from Scottish Government on sewerage and drainage (see below for key points on drainage), as there would be for water supply.

- There was no consensus on how best to manage CSOs, with participants expressing mixed opinions. Some saw Scotland’s current approach, where monitoring and upgrading is done for sewers identified as priorities, as acceptable, more cost-effective and a better use of available resources. Others believed that all sewers should be monitored, due to concerns around the environmental impact of overflows, transparency and accountability.

- Everybody was thought to have some responsibility for reducing strain on the sewerage system, including government, businesses and individuals. Manufacturers were seen to have a particular responsibility to ensure products that are not flushable are accurately labelled.

Key points: drainage systems

- Participants were aware of surface water flooding (particularly in the context of Storm Babet in October 2023 that occurred during the research fieldwork period) across Scotland and in their local areas. However, upon hearing more information about the water resilience challenges Scotland faces participants were again struck by the scale of the potential impacts of climate change on drainage systems.

- Again, there was a widespread view that everyone has some responsibility for reducing surface water flooding. Local authorities were seen to have a particularly important role, given their responsibility for maintaining local roads and drains. Participants also noted that local authorities’ role in deciding local planning permission and enforcing planning regulations means that they are in a position to ensure more Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SuDS) are integrated into new developments.

- Participants were generally positive about the potential for using blue-green infrastructure solutions to improve surface water drainage. The multiple community benefits of this approach stood out, as well as the opportunity to involve communities more in the design process. However, there were some concerns around the practicality and effectiveness of implementing blue-green infrastructure across different areas. While participants acknowledged that in certain cases, ‘hard engineering’ solutions might be the most practical option, there were also concerns around expense and disruption.

- Overall, participants acknowledged that a mixture of both blue-green infrastructure and hard engineering solutions would be needed to tackle surface water flooding in Scotland. There was a call for a more pro-active approach, with more investment, partnership working and use of local knowledge.

Key points: awareness-raising, communication and engagement

- Throughout the dialogue, participants highlighted the importance of raising awareness about the current and future impacts of climate change on Scotland’s water. Regarding how to raise awareness, participants felt that education in schools would be key, along with widespread and effective communications campaigns including targeted communications to reach specific groups within the population, such as homeowners and tenants.

- Participants felt that better informing the public about the need for reducing water usage – and adapting water supply and waste water services - to help tackle the impacts of climate change could help the Scottish Government and Scottish Water to build support for future decisions. They identified information needs around what the necessary water-related behaviour changes are, how behaviours can be changed, and the positive impacts of doing so.

- There was a strong view that the way in which people consume media and advertising has changed, for example it was thought that people engage less with television advertising and more with social media. Participants felt that communications strategies must reflect this. However, participants thought that multiple mediums would be needed and advocated targeting and tailoring communications to specific groups.

- There was a desire for community-level awareness-raising and engagement. It was thought that local knowledge is valuable and should inform plans to adapt or improve water and wastewater services in local communities. Participants also suggested that this should go further than simply consulting communities, for example that there should be a way for individuals to initiate changes that they want to see in their local community (such as suggesting changes to the streetscape to allow for more planting) in regard to water or wastewater issues.

Value of taking a deliberative research approach

- In total, 41 participants took part in 15 hours of deliberation across 5 dialogues. The deliberative approach gave participants the time and opportunity to learn about complex and often unfamiliar issues, before working together to develop thoughtful conclusions for the future of Scotland’s water resources and sewerage and drainage systems.

- It was striking that following the extent of their deliberation, and the scale of the challenges facing Scotland’s water due to climate change, participants were not defeatist. Rather, they expressed their desire for Scotland’s water sector to look to the future and put solutions in place rapidly to adapt to the impacts of climate change on water, sewerage and drainage, including innovative approaches. The research findings indicate that, given the time and space to consider the issues, consumers are clear that they themselves can and should be part of Scotland’s transition to a more resilient and sustainable water sector.

2. Contexts, aims and methodology

Background to the research

Consumer Scotland is a Non-Ministerial Office that came into existence in April 2022 following passage of the Consumer Scotland Act 2020. It exists to advocate on behalf of all consumers in Scotland and to represent consumers’ interests. It receives specific levy funding to advocate for consumers in the water sector in Scotland as part of this.

The climate crisis is inextricably linked to water. Climate change is increasing variability in the water cycle, thus inducing extreme weather events, increased flooding, reducing the predictability of water availability, decreasing water quality, and threatening biodiversity. How water and wastewater services can contribute to a just transition to net zero, and how these services should be adapted to mitigate the impacts of climate change, are key issues that Consumer Scotland is focusing on. As set out in its Strategic Plan 2023-27, Consumer Scotland recognises consumers’ choices will be key both in achieving net zero and in adapting to the impacts of climate change.

To tackle climate change, Scotland has an ambitious target of reaching net zero by 2045[1]. Rapid progress in the coming years will be essential if Scotland is to achieve its climate targets. Alongside actions to reduce emissions, the Scottish Government has set out its commitment to adapting and building resilience to climate change and the far reaching impacts it will have on society, the economy and the environment. The second Scottish Climate Change Adaptation Programme[2] (SCCAP2) set out over 170 policies and proposals to respond over the period 2019 to 2024 to the risks for Scotland identified in the 2017 UK Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA2). At the time of writing, the Scottish Government are consulting on their third Scottish National Adaptation Plan[3] (SNAP3) which reflects the updated UK assessment of the 2017 UK plan in 2022. Scottish Water has also published its own Climate Change Adaption Plan 2024[4].

In November 2023 the UK independent Climate Change Committee’s (CCC) second independent assessment of progress in adapting to climate change in Scotland[5] concluded that overall progress on adapting to climate change in Scotland remains slow, particularly on delivery and implementation. The CCC set out 51 recommendations to Government, including: setting out targets and supporting measures for reducing water use by business; that the consultation on water sector policies planned for 2023 should include proposals for setting clear drought resilience standards under a changing climate; and other recommendations relating to flood risk and resilience and to Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) and blue-green infrastructure.

Water and wastewater policy and management have a fundamental part to play in tackling climate change in Scotland. Managing water resources is essential to ensuring the resilience of Scotland’s communities, businesses and ecosystems against the effects of climate change. Scottish Water has recently called on consumers to use water as efficiently as possible in homes and gardens to help protect and maintain our water supply. This drive for water efficiency is also supported by Scotland's National Water Scarcity Plan[6] which sets out how the water sector will manage water resources in periods of low rainfall, and the roles and responsibilities of the key industry stakeholders.

At the time of writing the Scottish Government is undertaking a major review of water policy in Scotland, both to take account of the impacts and challenges of climate change and to ensure the current legislative landscape supports climate change ambitions. Its consultation on water, wastewater and drainage policy[7] opened on 21st November 2023 and closed on 21st February 2024. Consumer Scotland’s research will contribute towards a future water policy framework that places consumers at the heart of adaptation and resilience to climate change.

Research objectives

Against this backdrop, Consumer Scotland commissioned Ipsos to deliver a programme of deliberative research with the primary aim of helping to build its evidence base, providing insight into how domestic consumers can and should be part of Scotland’s transition to a more resilient and sustainable water sector.

The research sought to explore consumer behaviours, perceptions, tolerances and priorities, and importantly, what support is required by consumers to evolve water behaviours so that they are more sustainable in future. It focused on three key areas: household water use and disposal; water sector wastewater management (as it relates to the water environment); and surface (rain) water management at community level and rainwater capturing / re-use at household level.

Specific objectives were to:

- Find out the extent to which consumers are aware of climate change impacts in the Scottish water sector and whether they understand the need for adaptation;

- Consider what information is needed and in what format to support informed consumer decisions;

- Understand consumers’ views on a range of policy options and solutions relating to water resources and services, sewerage and drainage;

- Explore consumers’ views on where responsibility should lie for tackling the impacts of climate change on water in Scotland, how urgently this needs to be done and what considerations should be taken into account;

- Seek to understand the motivations, the opportunities and the support required by consumers to change their water behaviours to be more sustainable;

- Use a deliberative approach to allow consumers to be presented with information and options and to consider their responses.

Methodology

A deliberative approach was chosen for this research due to the complex and multi-faceted nature of the topic. Deliberative engagement is about putting people – through informed discussions, involving diverse perspectives, and understanding lived experiences – at the heart of decision making. It differs from other forms of engagement in that it allows those involved to spend time considering and discussing an issue at length before they come to a considered view.

The specific methodology used is known as a public dialogue. Public dialogue is a process during which members of the public interact with specialists, stakeholders and policy makers to deliberate on issues relevant to future policy decisions.

The dialogue brought together a group of 41 people from across Scotland to learn about the topic of the impacts of climate change on water, wastewater and drainage. The group met over five three-hour online workshops between October and November 2023 to answer the following key question: “How should we deal with the impacts that climate change is having – and will have – on water in Scotland?”

Over the course of the public dialogue, participants listened to presentations from specialists from across the water sector in Scotland, learned about the key issues in relation to the impacts of climate change on water, wastewater and drainage, discussed possible strategies and solutions to help address these impacts, and then drew conclusions together (which are presented in this report).

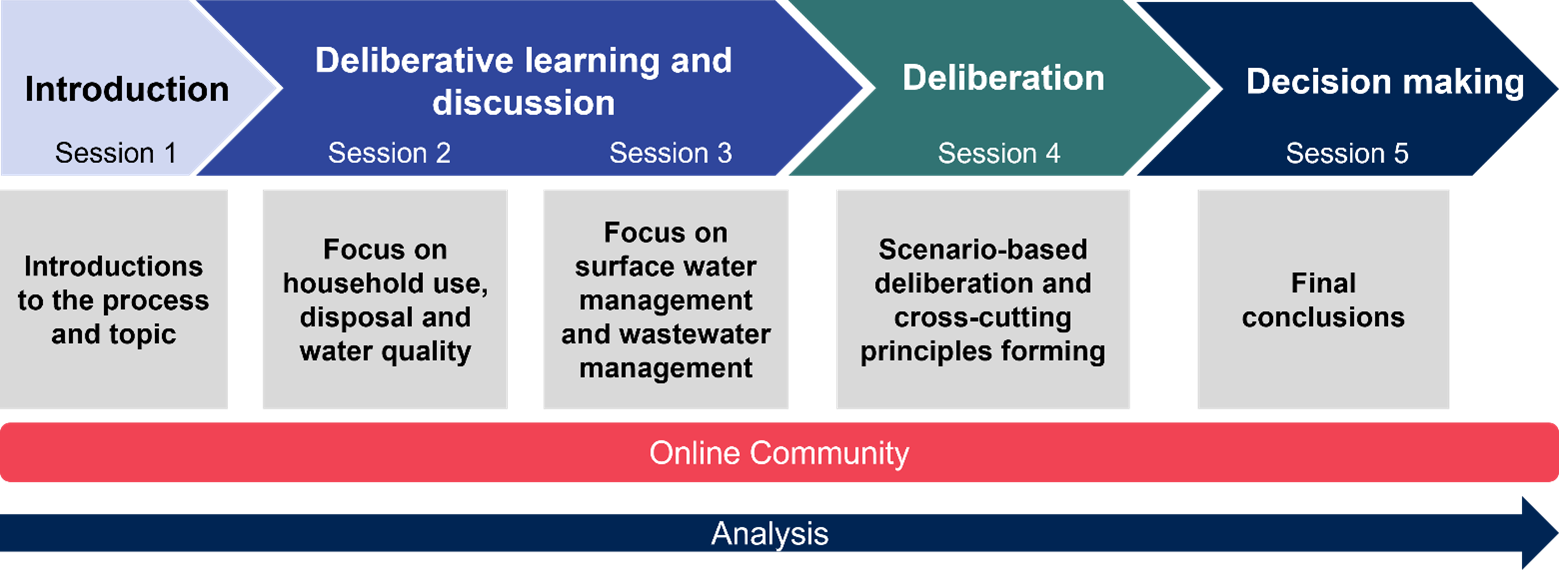

Further details about the process (including an overview of each session with date, times, content and specialists) can be found in Appendix A, but the overarching design of the dialogue is summarised in Figure 1.1 below. Alongside the online meetings, an online community helped support ongoing engagement with participants, facilitating continued learning, reflection and discussion.

Figure 1.1: Structure of the dialogue

Stakeholder engagement

In the early stages of the project, Ipsos facilitated a workshop with Consumer Scotland and a range of stakeholders from across Scotland’s water sector to help shape the design of the dialogue. The workshop explored stakeholder views on the options for adaptation and mitigation in the water sector, possible trade-offs and impacts, and likely future dilemmas that could benefit from public insight. Findings from the workshop informed the design of materials and helped to identify suitable specialists to present at the first three workshops.

Sampling and recruitment

The aim was to achieve a sample of at least 40 participants with over-recruitment to account for potential cancellations or drop-outs. In the end, 42 participants joined the first session and 41 continued to the end of the process.

Participants were recruited by telephone using a screening questionnaire. The questionnaire captured demographic information about the participants, designed to help ensure the group’s profile was broadly reflective of the Scottish population. Those aged 16-34, living in a rural or island area or more deprived areas[8], from an ethnic minority group, or with a long-term disability or long-term health condition were boosted to ensure sufficient representation of those voices. A table summarising the demographic profile of the group can be found in Appendix B.

To support and enable participation in all workshops, and in line with industry standards, participants were each paid £400 for joining the online sessions and online community. This was paid in instalments throughout the process. Participants were offered the loan of equipment if needed (including headsets, laptops or internet dongles) and were supported with training on how to use the technology and access the meeting platform. This allowed Ipsos to increase the diversity of those taking part. Workshops were also arranged to take place outside of regular office hours to increase participation.

Materials and input from from specialists

Discussion guides and stimulus materials were developed by Ipsos and reviewed by Consumer Scotland and stakeholders. A range of specialists from Scottish Government and Scottish Water joined at different points in the dialogue to provide information that would be useful for participants’ learning and deliberation (see Appendix A for details). Their presentations related to water and wastewater services, and the impacts of climate change on these (workshop 1); water resource planning, and household water use in Scotland (workshop 2); sewerage and drainage, surface water flooding, and ways of tackling the impacts of climate change on sewerage and drainage (workshop 3).

Presentations were delivered live and specialists stayed online to answer questions in a plenary setting, following smaller breakout discussions where participants had an opportunity to reflect on what they had heard and raise points for clarification. Any questions that were not answered during the live sessions were compiled in a Question and Answer (Q&A) document and posted on the online community before the next session (see Appendix C).

Participants were invited to join an online community, facilitated by Ipsos, which provided a secure space for participants to continue engaging on the topic in between workshops if they wished to (most opted to take part). Activities on the online community were designed and launched iteratively, so that they could be responsive to any issues that emerged from discussions and other events (such as Storm Babet, which caused mass flooding across the UK and particularly eastern Scotland and occurred between workshops two and three).

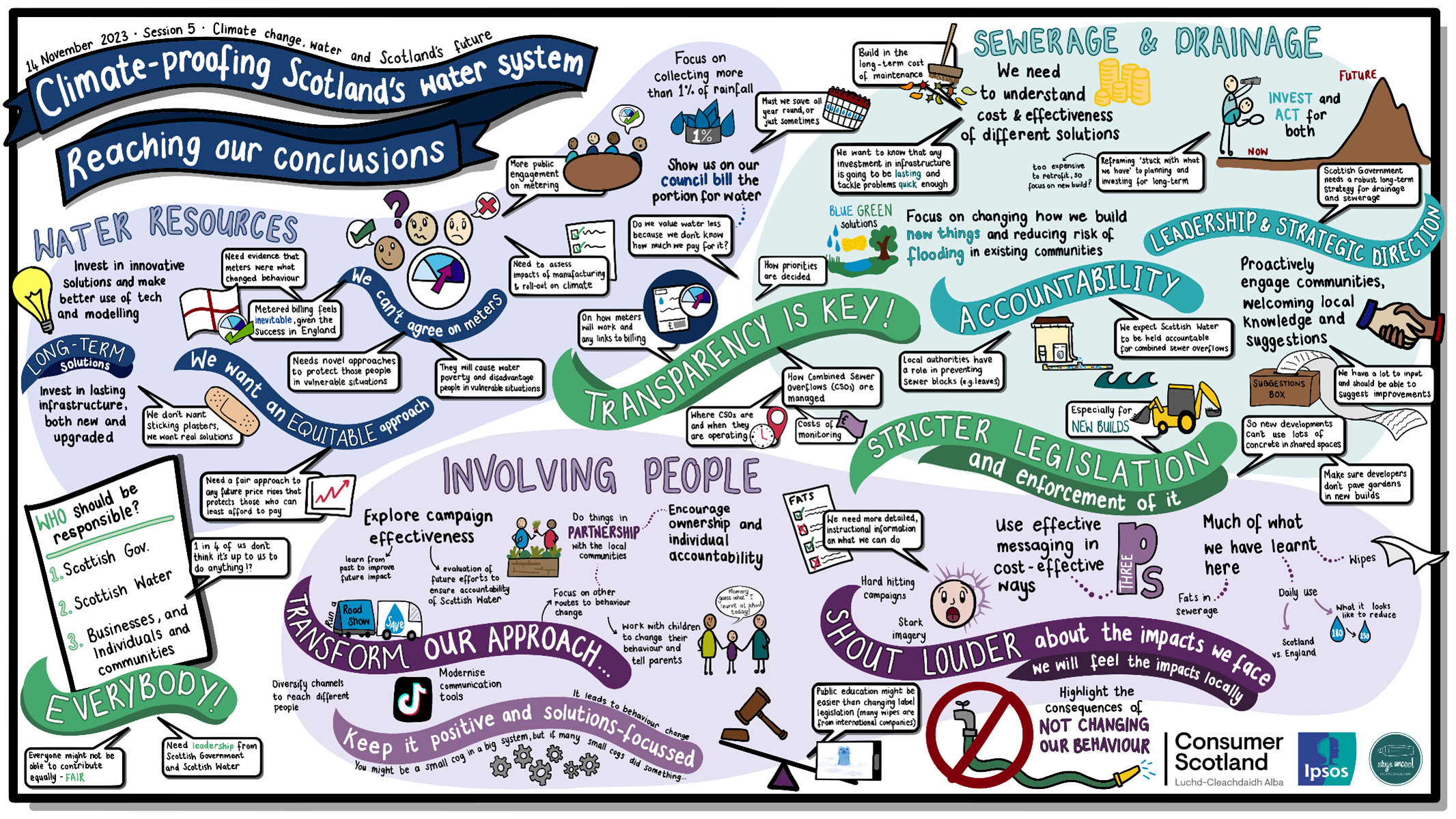

Visual summaries (by artist Skye McCool[9]) were also used throughout the online dialogue, which involved the use of drawings and text to convey the presentations, discussions and overall journey that participants experienced. These were used both as a learning tool, recognising different learning styles and preferred ways of accessing information, and as a way of engaging with participants via the online community in between sessions. An example is provided in Figure 1.2 below, and all five visual summaries can be found in Appendix C.

Interpretation of qualitative data

The conclusions set out and discussed in this report are intended to contribute towards the creation of a water policy framework in Scotland that places consumers at the heart of adaptation and resilience to climate change.

This report synthesises the diverse expressions of participants to draw out major themes of discussions and to draw attention to the way that they – individually and collectively – made sense of a complex topic, describing what mattered to them and why. On occasion, the report refers to verbatim assertions by participants and their understanding of the issues. These are not intended as authoritative statements of fact, but they tell us something important about how the issues can be perceived and understood by members of the public.

A robust and systematic analysis approach was used, with conclusions based on groups that are reflective of the diversity of the wider public. The deliberative nature of the project allowed for ongoing analysis throughout fieldwork, which ensured that emerging themes and principles that would form the basis of participants’ conclusions - both from workshop discussions and online community activities - could be played back as the dialogue progressed. Analysis does not seek to quantify findings nor does it indicate statistical significance from a representative sample. A more detailed summary of the analytical approach to the dialogue can be found in Appendix D.

The COM-B[10] behavioural model was used to inform the analysis of the data from this dialogue. This model recognises that behaviour is influenced by many factors and is widely used to identify what needs to change for a behaviour change intervention to be effective. According to this model, for any behaviour change to occur a person must have the:

- Capability – the physical strength, knowledge, skills and stamina to perform the behaviour;

- Opportunity – the behaviour needs to be physically accessible, socially acceptable and there must be sufficient time to do it;

- Motivation – they need to be more highly motivated to do the behaviour at the relevant time than not to do the behaviour (or to do something else).

Priority behaviours for water, sewerage and drainage were explored as part of this research. Participants focused on the perceived reasons underlying current behaviour in these areas, opportunities for - and barriers to - behaviour change, and the motivations for - and enablers to - behaviour change. The research team drew on the COM-B framework to support the analysis of water, wastewater and drainage behaviours in Chapters 2, 3 and 4 of this report.

This report offers insight into public perspectives on the key question posed to them after receiving and deliberating on essential information relevant to their task of considering how Scotland should deal with the impacts of climate change on water.

Figure 1.2: Illustration of how participants reached their conclusions

3. Water services and resources

This chapter summarises participants’ views on Scotland’s water resource management and approaches to tackling future water shortfall. It explores how participants balanced the need for investment in infrastructure and behaviour change at the consumer level in response to the impacts of climate change on water in Scotland. The chapter draws on findings from workshops one and two, in which participants learned about the current water infrastructure in Scotland, households’ water use, and the impacts of climate change on water resources. It also draws on findings from workshop four, in which participants considered scenario examples of infrastructure projects and consumer behaviours in relation to water resources, and from the online community, where participants continued to engage with issues relating to water services and resources in between sessions.

Key findings:

- Participants felt there should be a shared responsibility for tackling the impacts of climate change on water in Scotland, with the Scottish Government, Scottish Water, businesses, and individuals/communities all playing a role.

- To help tackle the challenges ahead, participants were broadly in favour of a new Water Efficiency Strategy, national water resource planning and more stringent standards for water saving measures in new build homes as possible actions. However, there was some surprise that these things were not in place already and questions over whether they were ambitious enough actions to meet the challenges ahead. Views on these ideas were underpinned by a strong sense of urgency.

- Participants felt that action to reduce household and business water use and infrastructure investment would both be required to tackle the impacts of climate change on water resources. Given Scottish Water’s ageing infrastructure, they recognised the need for investment and hard engineering solutions and wanted to see lasting solutions put in place.

- Even with infrastructure projects in place, it was broadly recognised that there would still need to be a focus on individuals reducing water usage. Participants felt that there would need to be guidance and support to help individuals make changes, and there were mixed views on the potential for water meters being installed.

- The support participants felt would be needed to facilitate behaviour change in this area included education and awareness-raising about the need to reduce water usage, guidance to help people make the necessary changes, harnessing technology to improve monitoring, and leadership from the Scottish Government to provide clarity on who is responsible for what.

Participants' starting point

Awareness of water in Scotland

At the beginning of the deliberative process, participants reported that they had limited knowledge of water in Scotland but were interested to learn more about it. While there was some awareness of where water comes from (e.g., reservoirs), it was widely felt that water is something that is available on demand and therefore not thought about.

“I turn the tap on, I get water there. That is my understanding.” (Participant, Workshop 1)

Participants broadly understood that they pay for their water through their council tax bill but were less sure about how their bill was broken down or how much they paid specifically for water. For instance, there was a view that paying for water through council tax band rates was unfair which was based on a perception that how much you pay could be determined by where you live. However, there was also relief that water is not metered in Scotland as this could make water charges more expensive for households using more water (such as large families).

“I’m kind of pleased we aren’t metered. I have three teenage children and a stinky dog. We do a lot of washing […] If I was being metered, I think I’d cry.” (Participant, Workshop 1)

Generally, participants had positive views of water in Scotland. When asked what words they associated with water, “fresh”, “safe”, “clear”, “good quality” and “taste” were mentioned. There was recognition that those living in Scotland are fortunate to have a supply of quality water compared to other places.

“I've lived in quite a few countries. Water was very, very minimal. I remember going out to a well with my clay pot to get water to bring back to my house [so] the word [I wrote down] was how lucky we are that we've got water in abundance. How long are we going to have this?” (Participant, Workshop 1)

Awareness of the impact of climate change on water

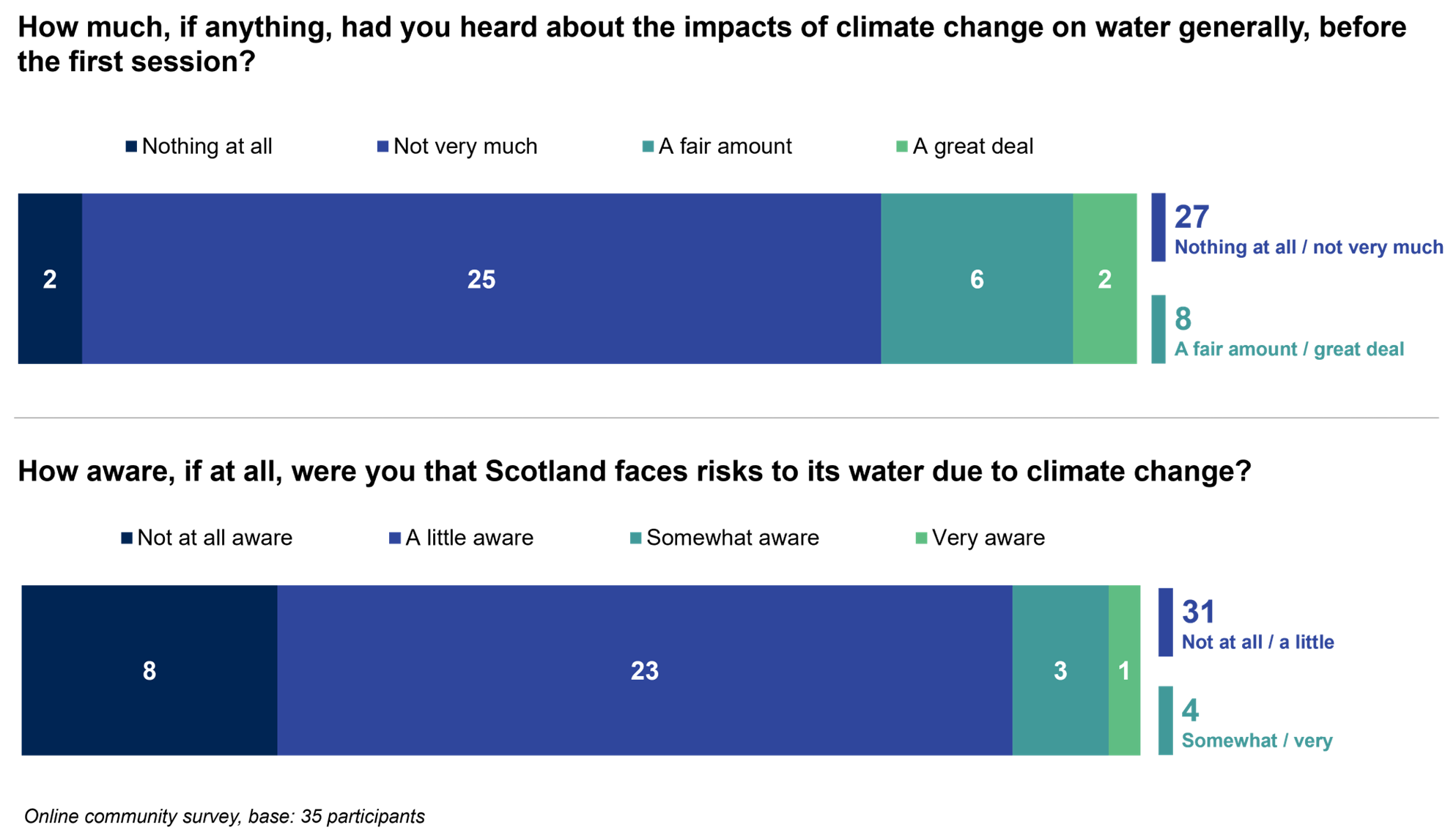

Most participants reported on the online community that before taking part in the first workshop they had heard ‘not very much’ or ‘nothing at all’ about the impacts of climate change on water, compared to a smaller number who had heard a ‘fair amount’ or a ‘great deal’. Awareness of the risks Scotland faced to its water due to climate change was also reported as low, with the majority feeling they had little or no awareness of these. Just over one in ten reported being somewhat or very aware of these risks (see figure 2.1 below).[11]

Figure 2.1: Knowledge and awareness of climate change impacts on water

Participants expressed alarm regarding what they heard in the presentations in workshops one and two about the impacts of climate change on water, and the challenges ahead for Scotland’s water resources. Impacts highlighted as being of particular concern were the increase in rainfall and the fact that Scotland would face both more dry days and more heavy rain and flooding. The presentations also highlighted projections, based on a moderate climate change scenario, that by 2050 Scotland could be running short of 240 million litres of water a day in a drought which would be expected to affect some parts of the country more than others. Participants, noting this, felt worried about the sizeable water deficit that Scotland could face by 2050 and the subsequent risk to customers of water not being available at certain times. Considering these impacts, participants were also concerned about the limited time left to take action to mitigate the worst of them.

There was a sense of reassurance that Scottish Water was planning for the future. However, questions were raised as to whether Scottish Water could achieve its plans to reach net zero by 2040 (five years earlier than Scotland and ten years earlier than the UK as a whole) while also dealing with the impacts of climate change on water services, and why it had been left until now to deal with.

“I thought the figures were quite terrifying. In terms of the climate change, but 240 million deficit, what they are doing, will it help with that figure?” (Participant, Workshop 1)

Participants generally felt the weather in Scotland had changed in the last ten years. Changes they had observed included: warmer and wetter weather; more prolonged periods of dry or wet conditions; typical seasonal changes being disrupted, more extreme and erratic changes in weather leading to flash flooding; and changes in wildlife (e.g., plants growing and blooming at different times to usual and fish species struggling). Some did not think the weather in Scotland had changed much in the last ten years, however this was a more exceptional view.

“Seasons are completely out of whack to what they used to be. You don't get the cold anymore. We used to get snow, we don't get snow anymore. It's completely different. The summer, you're getting a better summer because we didn't really get a summer before. You notice a big difference in the seasons.” (Participant, Workshop 1)

There was a general perception that Scotland would not be well prepared for extreme weather conditions. This view was based on past experiences of roads that had previously flooded and infrastructure that had been shut down by what participants saw as small amounts of snow. The COVID-19 pandemic was also highlighted as a recent example of the country’s ill-preparedness for emergencies. Participants felt that the level of preparedness may vary depending on the area, with places more used to experiencing extreme weather being able to cope better than places that had not experienced those conditions before. But it was also recognised that even if places are prepared for weather events happening now, they might not be as well prepared for extreme weather that could happen in the future.

Managing Scotland's water resources

Learning more about how water is used in Scotland and the impact of climate change on water resources, participants were surprised by the average amount of water used per person (180 litres per day) and that this is higher in Scotland than elsewhere in the UK. Participants were also struck by how “precarious” the water supply was, and the challenge ahead of managing wetter winters and drier summers.

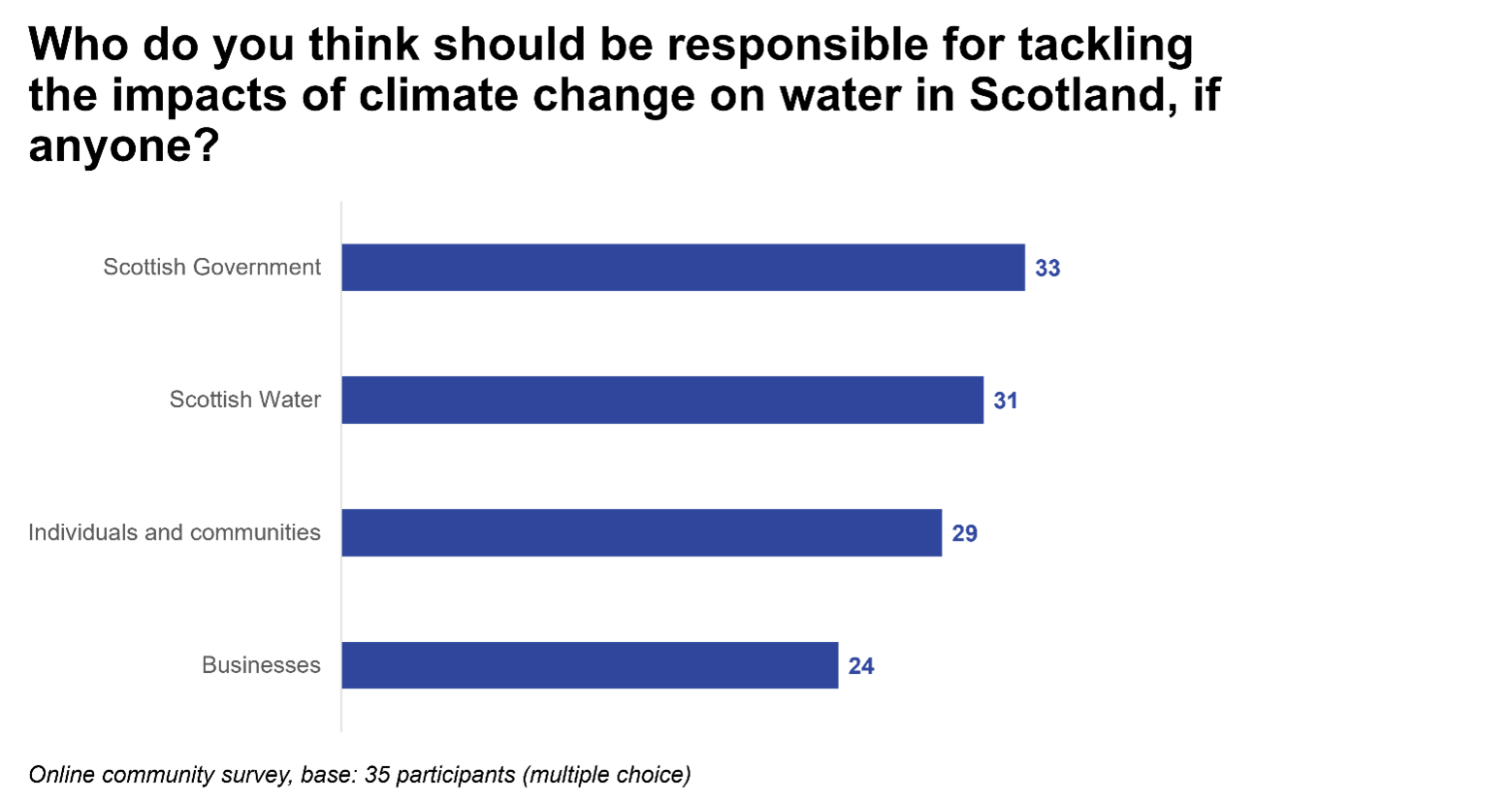

Who should be responsible and what roles should they play

At the beginning of the process, there was a general perception that there should be a shared responsibility for tackling the impacts of climate change on water in Scotland. This view persisted throughout the dialogue as participants considered the roles that different actors might play.

Figure 2.2: Responsibility for tackling impacts of climate change on water in Scotland

When discussing the roles that groups should play, participants felt that responsibility should cascade from the Scottish Government, through other organisations (such as Scottish Water, local councils, and businesses), down to individuals.

It was felt that the Scottish Government should take a lead role in coordinating initiatives to tackle the impacts of climate change on water. Participants defined this leadership as setting targets, regulating industry, and incentivising businesses, local councils and individuals to encourage changes.

“The government are the ones that have put in targets, environmental targets, so they have to take a lead role in helping organisations meet those” (Participant, Workshop 2)

Scottish Water were also thought to be responsible for providing leadership in terms of evidence and expertise. Working with the Scottish Government, participants saw a role for Scottish Water in providing information and a road map for the changes required.

“It may be worth representatives from Scottish Water going to Parliament and emphasising the impact and getting the people that know about climate change supporting them.” (Participant, Workshop 2)

Participants identified private sector businesses as being responsible for helping to tackle the impacts of climate change on water. This view strengthened over the course of the dialogue. In particular, it was felt that the role of businesses would be to find ways to reduce water use in their operations. For instance, those involved in the construction industry – such as architects and building contractors – were seen as having an important role in finding ways to reduce water use in homes, starting from how they’re built. It was also felt that manufacturers of white goods should be subject to stricter regulation to ensure they design products that are water-efficient.

There was a strongly held view that businesses should not pass the costs of any changes they need to make onto consumers, which was highlighted by those who felt there was too much emphasis on consumers, and not enough on businesses being accountable. This point was raised at various points throughout the dialogue and was ultimately reflected in the conclusions that participants reached by the end of the process.

“I want to see the construction industry [held] to account for where they build houses, how they build houses, businesses using large amounts of water. We cannot put the cost back onto domestic consumers because they can't pay it.” (Participant, Workshop 2)

It was also felt thatcommunities and individualsshould take responsibility for reducing water use at a local and household level. Ways in which people could reduce their water use is explored later in this chapter, but as highlighted above, this was qualified by a view that the burden should not fall on consumers to make changes ahead without more systemic action being taken and communicated to the public by the Scottish Government and Scottish Water, and without industry also making changes.

“We are responsible in our usage. […] It's in everyone's interest, for whatever reason, to at least keep the water system going […] From these sessions, I'm finding more and more that there is action being done, but apart from these sessions, I'm not aware of it to be honest.” (Participant, Workshop 2)

Policy ideas

In workshop two, participants were presented with a list of possible actions that the Scottish Government could take. It was emphasised that these are not current policies, but ideas that could be considered in future. Participants were generally underwhelmed by the ideas presented (see figure 2.3); while they were viewed as good ideas, there was some surprise and concern that they weren’t actions that had already been taken. There was also a view that these actions didn’t go far enough, and needed to be more imaginative and ambitious to deal with the water resource problems that Scotland faces.

"If they're not doing these things already, what are they doing?" (Participant, Workshop 2)

Figure 2.3: Possible future policy options

Views on the various possible actions were underpinned by a strong sense of urgency.

“If we sit doing nothing, we’re not going to get anywhere… We need to be moving forward, but keep an eye out for other solutions.” (Participant, Workshop 2)

There was also a sense of frustration, based on a perception that the Scottish Government and Scottish Water had been slow to react to the water resource challenge.

“It feels to me that Scottish Water (and presumably the Scottish Government) know the problem but are slow in developing a strategy to tackle it.” (Participant, online community)

The possible actions that resonated most with participants included:

- A new Water Efficiency Strategy, which was generally thought to be the most important policy because it would underpin all the others. However, it was also felt to be too vague: "This sounds like a government soundbite with no detail - it is meaningless." (Participant, Workshop 2)

- National water resource planning, which was felt to be a “common sense” approach and would tie in with the water efficiency strategy. There was a view that this could encourage consumers and businesses to consider what are essential and non-essential uses of water: “There are different levels of water requirement. There's a level of basic need and what water is used for and then there are things that are nice to have.” (Participant, Workshop 2)

- Setting more stringent standards for water saving measures in new build homes. This was broadly felt to be a good idea, but participants had some concerns about it. While it was pointed out that it could take a long time before the benefits would be felt, and might not be quick enough to mitigate the immediate risks to water resources, some questioned why it should take a long time. Participants also challenged the fairness of prioritising new builds, which could mean those living in older homes being left behind: "These things do tend to take a little bit, well, a lot of planning. I don't see why it should take ages. The new council houses around here already have solar panels. I don't see why saving water measures should be any harder really." (Participant, Workshop 2)

There were more mixed views on:

- Introducing a National Catchment Risk Assessment for emerging contaminants. This stood out to some in terms of the immediate impact on people’s health, which was seen to be an important factor. Others were less clear about how this would contribute to tackling climate change, and there was a view that communications around this could come across as scare-mongering: “You could create fear unnecessarily for no benefit.” (Participant, Workshop 2)

- Changing legislation so that water shortage orders can be put in place quickly. A view expressed by participants was that this would be a good way – albeit potentially inconvenient for some households – to manage water resource challenges efficiently and fairly in future: “That's important for an immediate solution, otherwise people will run out of water and other people waste it on their garden.” (Participant, Workshop 2). Another view was that this would be the least important action, based on the perception that droughts were rare in Scotland. It was felt that this would need to be done carefully to avoid negative impacts on vulnerable groups (such as the elderly) and there was a call for clearer communication, as some thought previous hosepipe bans had included Scotland.

Tackling Scotland's future water shortfall

As previously highlighted, participants were alarmed by the water deficit that Scotland would face by 2050 and the risk to customers of a water shortfall. The presentations in workshop two outlined various ways to mitigate against such risks and participants discussed the possibilities of building (or upgrading) infrastructure and the role of households in reducing water use.

Infrastructure building and upgrading

There was initial surprise among participants about the age of Scotland’s infrastructure, particularly that some of it was built in Victorian times (as was highlighted in a presentation in workshop one). Reflecting on this, one view offered by participants was that the water infrastructure would need to be upgraded, while another was that it should be maintained if it is still functioning.

“We always think new stuff comes along and is going to be so much better. But it isn't necessarily.” (Participant, Workshop 1)

When considering possible infrastructure projects, there was a broadly negative reaction to infrastructure-heavy solutions, such as building new dams or new pipelines to move water to areas where it is needed. This was based on concerns over the costs involved and the negative environmental impacts, which were felt to be unacceptable. While there was some acceptance that a certain amount of disruption could be offset by an effective solution, there were doubts over how effective they would really be.

“We've got to be thinking in a more sustainable way, this is not sustainable. There are ways, there have to be ways to do this that isn't destroying stuff that is supporting the environment and sustainable.” (Participant, Workshop 2)

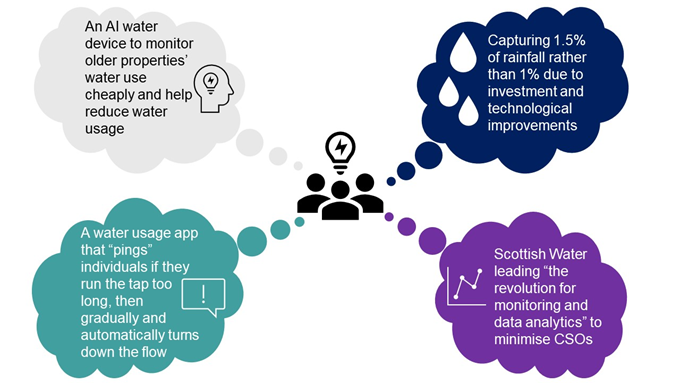

Instead, there was a preference for more localised solutions and updating existing infrastructure, which it was thought would have less of an environmental impact. Participants were surprised to hear in the presentation that only 1% of rainfall in Scotland was captured and queried whether infrastructure could be improved to enable more rainfall to be captured and stored. Use of grey water was also highlighted as an alternative means of tackling the water shortfall while minimising environmental impact.

“Wouldn't it be great if a strategic objective was to capture more than 1% of rainfall. How do we do that? That doesn't seem enough. The more you think about it, the amount of rain we had this weekend, and you couldn't get it.” (Participant, Workshop 2)

Discussions around infrastructure building and upgrading were underpinned by a strong view that the cost of this should not be borne by consumers alone, and that low income households should be protected from any rising costs.

“Everyone already knows about the current financial situation and I'm not sure the public would stand for any more rising costs. People are already struggling as it is and the last thing they need is more financial worries in my opinion. So ultimately, it comes down to the cost both in the immediate and longer term for people.” (Participant, online community)

Role of households

Even with infrastructure projects in place to tackle the water shortfall, it was broadly recognised that there would still need to be a focus on individuals reducing water usage.

As well as suggesting larger scale infrastructure for rainfall capture, there was an appetite for collecting rainfall at a household level. Participants were also supportive of consumers installing water-saving devices such as water butts for gardens or water hippos for toilets. As highlighted above, there was broad agreement that product labelling would encourage businesses to make, and consumers to choose, more water-efficient products. However, it was recognised that not everyone would be in a position to take up these actions.

“It's easy for me to buy a rainwater butt to collect gutter water. Someone in a council flat with limited means isn't going to spend £40 on a water butt.” (Participant, Workshop 2)

It was felt that consumers would need guidance on what devices are available, how to obtain, and how to install them. To ensure those on lower incomes were not left behind, it was suggested that Scottish Water or local councils could provide some devices for free.

“Responsibility falls on Scottish Water […] to teach us [and] put the right infrastructure in place for us to be able to guide us.” (Participant, Workshop 2)

Participants also discussed the possibility of water meters being installed in households and there were mixed views on this. Those who were supportive of meters for monitoring purposes felt that they could help make people more aware of their usage and therefore more likely to take action to save water. At a national level, meters were seen as a means of gathering useful information on where water usage was highest so that campaigns to reduce usage could be more targeted.

“If people don't know what they're using and don't have a clear idea that they're using a lot or not using a lot, how will they ever be incentivised to change their behaviour?” (Participant, Workshop 4)

Participants who had previously lived in an area of England where metering takes place were surprised to learn about the low number of water meters in Scotland. It was suggested by participants that Scotland’s higher water usage compared to England could be due to this lack of metering. Participants who reported positive experiences of using an energy meter felt that water meters would have a similar impact, although others did not consider their energy meter to have been very effective in reducing energy use. While there was less support for water meters being linked to billing, there was a view that this would be more effective at reducing household usage than monitoring alone. It was also suggested that water meters could be gamified to encourage engagement with water saving, and that customers could be encouraged to reduce water usage with discounts and offers.

“It's only when there is a financial impact that people will change their behaviour.” (Participant, Workshop 4)

However, where participants were opposed to meters, this was based primarily on concerns about them being linked to billing. There was a view that they could be a catalyst for water poverty and would penalise some groups, such as those on low incomes, those with large families, and those with disabilities or health conditions. For example, one participant with a disability described needing to use more water sometimes for pain relief or for cleaning medical equipment and felt they would be “punished” for it. It was strongly felt that linking usage to billing would be unfair to people who need to use more water and to those already struggling financially.

“I deal with people who are living in frozen houses because they can’t afford heat. Those people are now going to go thirsty and dirty as well.” (Participant, Workshop 4)

There was also a perception that water meters would be controlling and invasive. It was therefore felt to be important that water meters (if introduced) would be rolled out carefully and not forcefully.

“There's a perception that installing meters is a form of control, in terms of society. If they were to be mandated, then look what's happened down in England. Bailiffs have forced entry into vulnerable people's homes to install smart meters.” (Participant, Workshop 4)

Changing consumer behaviours

There was widespread recognition that behaviour change would be an important factor in tackling the impacts of climate change on water in Scotland.

Current behaviours

Early in the dialogue, participants reflected on their own behaviours in relation to water. Some reported that they already make an effort to reduce water use. There were a range of motivating factors behind this, including:

- Financial, i.e., trying to minimise use of hot water to save money (such as by saving all the dishes to do one load of washing up).

- Better awareness of water as a finite resource and growing concern about climate change.

- Habit or upbringing: those who had spent time in other countries said they were used to using minimal water, while others said they were brought up very conscious of their water use.

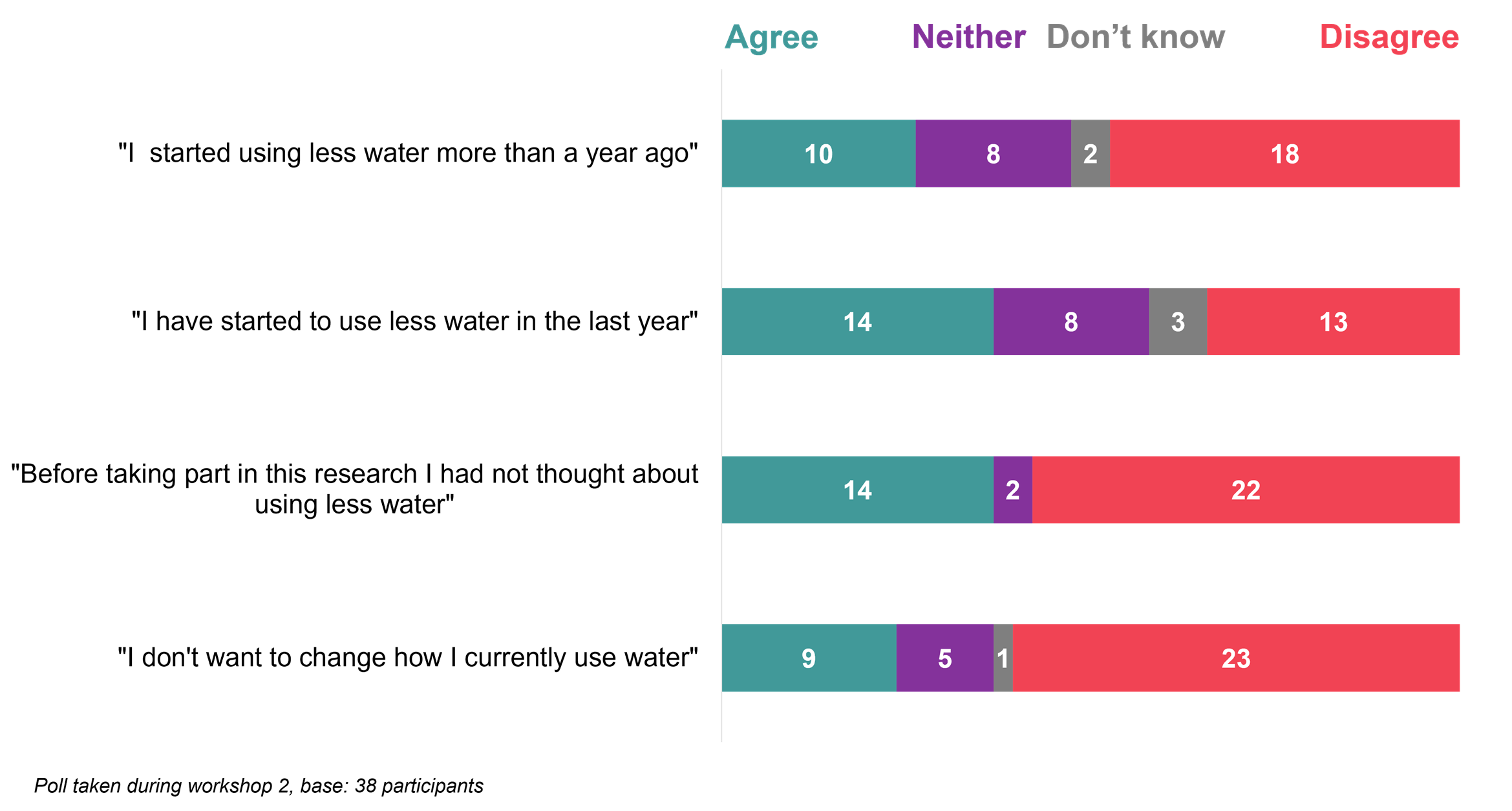

However, this was not widespread. A poll conducted at the start of workshop two (see figure 2.4) found that just over a quarter of participants reported that they had started to use less water more than a year ago, while just under half said they had not done this. When thinking about the last year, just over a third of participants reported that they had started to use less water, although a similar number had not.[12]

Figure 2.4: Poll results from workshop 2

Others described being conscious of water but felt limited in their ability to reduce their use. This reflected the workshop two poll results, which found that over half of participants disagreed that they had not previously thought about using less water and an even higher number disagreed with the statement ‘I don’t want to change how I currently use water’ (see figure 3.4 above). Groups identified as needing to use more water included those with disabilities or health conditions, households with larger families, and those working in certain industries (such as farmers).

While some felt that they currently try to conserve water, or are conscious of their water use, others felt it was something that they don’t think about. There was a perception that people in Scotland may be more wasteful than other countries, and participants suggested that this could be because of the absence of metering. However, it was also recognised that using less water might be more challenging for people not already in the habit of doing so.

"In my mind it's just an endless supply. So these conversations make me a little bit more aware of the reality of that and the implications." (Participant, Workshop 2)

Participants were given the opportunity to try a water calculator,[13] which was posted as an activity on the online community. There were a range of reflections among those who used the calculator. Some were surprised to find their water use was below average, which others were surprised to see how much they were using. While there was some interest in the water saving ideas and products that the calculator suggested, they were not considered to be useful or realistic for all households.

“Interesting. Looks like I’m doing not too badly but I could do better. I’ll certainly try out a few of the suggestions.”

“Bit shocked at how much water is wasted. I honestly didn't think it was that much. I will try harder to stop this and think of water wastage.”

(Online community responses)

Initial views on water behaviour change

There was broad agreement that behaviour change would be important and, as highlighted above, there was a sense that there should be collective responsibility for how water is used in Scotland. A short survey on the online community found that nearly all participants believed that it would be possible for them to cut their own water usage down ‘a little’ or ‘somewhat’, while one participant felt they could cut it down a great deal. No participants felt they could not cut down their water usage at all.

Nevertheless, initial barriers to behaviour change that participants identified were a lack of awareness or understanding of the need to reduce water usage. It was felt that this lack of understanding could be exacerbated by messages that appear contradictory, such as that there will be more rainfall but we will need to use less water. A lack of interest in issues relating to water and a lack of incentive to change were also highlighted as possible barriers, based on a view that people may not care enough to change their behaviour and might only cut down if they had to pay for what they used.

Priority behaviours: barriers and enablers

There are multiple consumer behaviours relating to water. For example, recent Consumer Scotland survey research on decarbonisation captured respondents’ views on 11 different water-related behaviours and identified self-reported perceptions of their impact on the environment.[14] As it would not have been possible to cover all these behaviours in the available workshop time without compromising on coverage of other research objectives, Consumer Scotland identified six priority behaviours for exploration in workshop four: two relating to water, two to sewerage and two to drainage. This section focuses on the two water behaviours participants discussed, which were reducing time spent in the shower and fixing plumbing leaks from pipes and toilets. Participants explored the barriers and enablers to behaviour change in these areas.

Reducing time spent in the shower

As highlighted in earlier discussions around potential barriers to behaviour change, lack of knowledge and understanding was identified as a key reason why people might spend longer in the shower than is necessary. In particular, there was a view that people might not be aware of how long they take in the shower, and whether this is too long. Another view was that people might think they need longer showers to be clean, or might stay in longer to follow instructions on hair or body products (for example a hair conditioner advising you to apply and leave in the product for five minutes). It was also felt that inefficient shower systems would prevent people from wasting water in the shower.

Participants identified particular groups who might find it difficult to reduce the time spent in the shower, such as those in jobs that are physically demanding and those with a disability or health condition. It was also recognised that showers can be relaxing for some people and so they might not want to stop doing something they enjoy.

“People rely on baths and showers during the winter season for chronic pains and helping to open up sinuses and airways. A lot of people will take longer to shower if they have a wound which can’t be touched. Also stoma bags. If you have a leak or it’s burst it will take longer to shower.” (Participant, Workshop 4)

To enable behaviour change in relation to time spent in the shower, participants suggested:

- Shower timers to help people become more aware of their shower time, or a timer that switches the shower off after a period of time;

- Awareness-building campaigns to improve understanding about the value of water and the necessity of reducing time spent in the shower;

- Improvements to shower technology to make showers more water-efficient;

- More holistic healthcare (in terms of NHS services) so that those with disabilities or health conditions have alternative ways to manage their conditions without longer showers.

Fixing plumbing leaks from pipes/toilets

Lack of awareness and knowledge were highlighted as key barriers in relation to households fixing plumbing leaks, as it was broadly felt that people might not know they have a leak or how to fix it. Further, if a leaking pipe was not causing any obvious damage or affecting any appliances, it was reasoned that people may not be motivated to fix the issue. It was also suggested that in some circumstances, such as in rental properties, it might not be clear who is responsible for fixing a leak. The cost of fixing was identified as a further barrier, along with the perceived lack of availability of tradespeople.

To enable behaviour change in this area, participants suggested that:

- People would need to know how to identify and fix leaks;

- It would need to be clear who is responsible for fixing leaks (for example in a rental agreement);

- Grants to reduce any cost barriers and encourage people to make improvements affordably;

- Community hubs to provide support in dealing with plumbing issues;

- More tradespeople should be trained to meet demand;

- Awareness-building campaigns should be run to educate people on the consequences of not fixing a problem to make it more of a priority for people.

The balance between behaviour change and infrastructure

It was broadly recognised that dealing with the impacts of climate change on water would require both behaviour change and infrastructure changes. However, when participants considered two different scenarios (see appendices) in the fourth workshop, to explore the relative roles of behaviour change to use less water and of building or upgrading more infrastructure, their views were mixed on the emphasis that should be placed on each of these. One scenario outlined a future in which people in Scotland “use much less water” and less building and upgrading of infrastructure is needed than might otherwise be the case to ensure sufficient water supply. The other scenario set out a future where households and businesses “use somewhat less water” and more building and upgrading of infrastructure is carried out to increase the supply of water.

Those in favour of using somewhat less water, and focusing more on building and upgrading more infrastructure, felt this would be more effective if done right. This was based on the view that people cannot be relied upon to make the changes required, so the impact of this could be limited.

“There’s only so much benefit you can get from getting consumers to reduce their water usage […] investing in the infrastructure is going to be the bigger driver than getting people to use less.” (Participant, Workshop 4)

Those in favour of using much less water, and building and upgrading infrastructure less, felt that infrastructure changes would take too long. Instead, focusing on behaviour changes to reduce water usage was seen to be a more efficient and sustainable approach, and would be more important at particular times, such as during droughts. When it came to forming conclusions, this view proved most compelling, leading to participants emphasising the role of reducing water use over infrastructure investment

“Once you change people’s behaviours it’s easier to sustain. Keep building additional capacity but you banked the investment in demand reduction.” (Participant, Workshop 4)

However, the sense of urgency to deal with the impacts of climate change on Scotland’s water, for some, meant that the emphasis needed to be on both reducing water use and building and upgrading more.

“What we’re seeing and what we’ve talked about, 10-30 years is a hell of a long time. We need to act quicker than that. We’ll run out of water. I think we have to act quicker than that. I think the only way to do that is to make the investment and at the same time reduce and improve the water efficiency of how the general public use their services.” (Participant, Workshop 4)

Forming conclusions on water services and resources

Based on participants’ discussions on how to tackle the impacts of climate change on water services and resources throughout the process, a draft set of conclusions were presented to them in the final workshop.

Participants were broadly in agreement with the draft conclusions on how to tackle the impacts of climate change on water resources and services, feeling that these were overall a fair representation of key points. However, they also suggested some additions and clarifications to provide more nuance, which are outlined below.

Reflecting earlier discussions around the role of different groups, participants wanted even more emphasis in the final version of the conclusions on the importance of leadership from Scottish Government, including ensuring there is a set of guidelines and targets for Scottish Water to adhere to. While it was recognised that a collective effort would be required from government, industry and citizens, without leadership from the top and clear communication between the parties involved it was felt that the situation would not be tackled effectively. Participants also wanted to be reassured that Scottish Government and Scottish Water were working effectively together in partnership, and that the public would be clearly communicated with so that people can start to be invested and feel part of the change. Related to this, participants also wanted to emphasise that businesses should reduce their water use as well as consumers.

Future-proofing Scotland’s water resources and services was also seen as fundamentally important. Participants were clear that it was vital to take action now and emphasised that it is not only future generations that will be impacted by climate change, but also everyone living in Scotland at the current time. They also wanted to know that Scotland was investing in solutions that would last into the long term, rather than short-term ‘sticking plaster’ solutions.

When discussing the relative emphasis that should be placed on reducing water use and investing in infrastructure to help with demand, there was a view that change could happen more quickly on the behaviour change front, while infrastructure investment would take longer to make a difference. When it came to ratifying the conclusions, participants were therefore keen that action to reduce water use should be mentioned first before infrastructure investment.

Participants also added a point about the importance of Scotland investing in more innovative approaches to tackling the impacts of climate change on water resources. For example, there were suggestions for greater use of digital technology in metering (if introduced) and in the monitoring of local and regional water usage. They were keen to hear about examples of innovation from other countries that could potentially be introduced in Scotland, including the use of new technologies.

When it came to people reducing their water use, there was some awareness of different norms about water use in other countries, where water shortage is a huge problem and it has become a way of life to save as much water as possible. Following discussions around possible measures to conserve water, they felt that more clarity is needed on whether people should try to save water all year round or only at certain times of year, such as the drier summer months.

Although participants saw it as important to conserve water, there was also surprise expressed at Scottish Water currently capturing just 1% of rainfall[15]. Participants queried whether Scottish Water should aim to capture more than this amount, and whether if this was done it could mean that there would be less need for people to cut down their usage. However, they also noted that if this is not currently done because of the carbon cost of capturing and cleaning a higher proportion of rainfall, this should be explained to the public.

Participants emphasised the importance of the point (already in the draft conclusions) that any changes put in place to tackle the impacts of climate on water should take an equitable approach, whereby those who would struggle to afford to pay and/or are vulnerable are protected. This came up particularly in discussions about potential price rises for customers; while participants agreed these feel inevitable, they were concerned that not everyone would be able to afford to pay, especially if businesses also passed any costs associated with their changes onto consumers as well. Media coverage about the UK water sector and increased scrutiny around executive salaries and bonuses that emerged during the fieldwork period for this research (including for Scottish Water) was also mentioned, with participants questioning how such bonuses could be justified when so much investment is needed.

In regard to infrastructure investment, there was a suggestion from one group of participants (also received positively by participants in other groups) that customer water bills could be itemised so people can see how much money has been spent on investment. This would aid transparency by giving people confidence in how resources are being used, which in turn could encourage them to play their part: “the more you inform people, the better chance you have of changing usage and behaviours” (Participant, Workshop 5).

On the potential installation of water meters that aren’t linked to billing, there was no consensus among participants either in the final workshop discussions or in previous sessions. The wording of both draft and final conclusions reflects these disagreements.

The group’s final conclusions, reviewed and ratified by participants based on the themes highlighted above, are presented below (figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5: Participants’ conclusions on tackling the impacts of climate change on water services and resources in Scotland

How should we deal with the impacts of climate change on water in Scotland?

Participants’ conclusions were that:

Managing our water resources

- Everyone needs to play their part in tackling Scotland’s water deficit: Scottish Government, Scottish Water, businesses and industry, people and communities.

- Scottish Government has a particularly important role to play, by leading, regulating and setting standards.

- There is a need both to take action urgently and to plan for the long term, as what we do now impacts both us and future generations. Both action to reduce water use and infrastructure investment are required.

- Scotland should invest in research and development into innovative approaches to tackling the impacts of climate change on water resources, including the use of new technologies.

People reducing their water use

- It is important that people and businesses understand the need to save water and do what they can to reduce how much they use. This will be challenging: some people and businesses won’t want to change, while others may not be able to.

- There is some support for installing water meters that aren’t linked to billing – this could help people to reduce their usage and lead to them valuing water more. However, participants questioned whether meters would make much difference if not linked to billing, and whether this would be a gateway to metered bills eventually.

Infrastructure

- Scottish Water’s ageing infrastructure needs more investment, so that lasting solutions are put in place – including both new infrastructure and upgrades to existing infrastructure.

- Price rises to pay for this feel inevitable, but negative impacts on people who can least afford to pay should be avoided.

- Participants wanted to see an equitable approach, where vulnerable consumers and those on the lowest incomes are protected.

4. Wastewater services

This chapter outlines participants’ views on how to approach current and future challenges facing Scotland’s wastewater (sewerage) system. The chapter draws primarily on findings from workshops three and four, in which participants learned about Scotland’s sewerage system and how it is being impacted by climate change, as well as potential solutions. Some data from the online community is also included, where this was relevant.

Key findings

- Participants had generally not thought much about wastewater services prior to this research unless they had a septic tank, and assumed this meant the system was working well.

- When they were presented with information about the combined sewer system in Scotland, there was some concern about the impact of CSOs into the sea, as well as surprise at the cost and the extent of sewer blockages.

- While participants acknowledged that changing the entire system would be too time-consuming and expensive, they felt that more should be done to improve the system and reduce the likelihood of CSOs. This included both updating the infrastructure and encouraging behaviour change to reduce the strain on the sewerage system.

- There were mixed opinions on which approach to monitoring CSOs is desirable in future. Some saw Scotland’s current approach, where monitoring and upgrading is done for sewers identified as priorities, as acceptable, more cost-effective and a better use of available resources. Others believed that all sewers should be monitored, due to concerns around the environmental impact of overflows, transparency and accountability.

- Everybody was thought to have some responsibility for reducing the risk of CSOs and reducing strain on the system, from individual behaviour change to leadership at a national level. Manufacturers were seen to have a particular responsibility to ensure products that are not flushable are accurately labelled.

- Behaviour change was widely seen as an important part of reducing the strain on Scotland’s sewerage system and minimising the risk of CSOs. Despite participants feeling they were relatively conscientious in relation to their own behaviours, it was thought more could be done. Participants also identified various barriers to change, however, and thought that certain groups may find it particularly hard, such as those with a disability or health condition or families with young children.

Participants' starting point

Participants using the main public sewerage system typically said that before engaging with this research they had not thought much about their wastewater services, apart from rare occasions where they had experienced an issue such as burst or corroded pipes. This was seen as a good thing however, as it was understood as an indication that the system was working well.

“From my perspective, the service is invisible. I would say that as a compliment. Unless you encounter an issue…an invisible service is a seamless service.” (Participant, Workshop 3)

During early discussions there were some concerns raised that sewage may be being released into the sea, based on news stories about this happening in England. One participant was worried that this may be the case for their wastewater, as they were unaware of any water treatment plants nearby.

Those who had experience of using septic tanks (or who knew somebody that did) described higher levels of awareness around their sewerage system, including how it worked and particularly what could or could not be put into it. This was put down to “having to care”, since they were responsible for maintaining it. Among those with a septic tank, there had been some negative experiences of blockages that had been unpleasant to deal with. However, there were also those who were very satisfied with their septic tank and had never had any issues.

“A constant electricity supply [is needed] to pump air down into the septic tank to get a secondary fermentation. When that stops working you get a terrible smell back through the house. You then have to get it emptied; you have to pay….” (Participant, Workshop 3)

“It is a clever system. […] I have no problems with my septic tank at all.” (Participant, Workshop 3)

Reducing the risk of Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs)

After participants were presented with information about combined sewer systems and how they worked, there was some surprise that rainwater goes into the same place as sewage and concern about the impact of overflows into the sea. In response to the fact that one per cent or less of storm water that is discharged into the sea is untreated sewage, there were mixed reactions. While this was described as a “pleasant surprise” given the recent controversy around this issue in England, others found it to be too high. Indeed, there was a view that the existence of any CSOs at all was unacceptable:

“I feel that we cannot allow raw sewage into the environment. [The presenter] said it was a safety measure to stop it filling up your bathroom instead, but I think we need a new approach.” (Participant, Workshop 3)

There was also some scepticism around this figure and concern that the true number of CSOs may be higher.

The high cost of fixing sewer blockages each year also stood out to participants, as well as the amount of blockages (around 80%) caused by inappropriate household items being put down the sink or toilet.

However, participants were very pleased to learn about ways in which bio-waste had been collected and reused. Solutions like this, which bring multiple benefits, were especially popular among participants.

Approach to reducing CSOs

In response to the new information, (see Appendix A for an overview of workshop three’s content) there was some discussion around whether the current system could be changed, for example by creating a separated sewer system or widening the pipes. However, following further deliberation and questions put to the speakers around the cost and practicalities of this, participants acknowledged that this may be unrealistic. There was appreciation of the scale of the problem, given the length and complexity of the underground pipe network and the amount of ageing infrastructure. While a different system would be ideal, participants recognised that this would be very time-consuming and expensive to change.