1. Acknowledgments

This report is based on survey research commissioned from The Diffley Partnership research agency, using the ScotPulse online panel. The interpretation of the findings and writing up of the report was undertaken independently by Consumer Scotland in fulfilling our general function of using data, research and analysis to inform our work on the key issues facing consumers in Scotland. Our thanks are due to those individuals that gave up their time to respond to the surveys.

2. Summary

Context

The Scottish and UK governments have both made commitments to achieving net zero emissions so that by 2045 in Scotland, and 2050 in the rest of the UK, we will no longer be adding to the total amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. However, for the transition to net zero to be a success, all sectors will need to play their part in tackling climate change. For consumers this will involve changes to how most of us travel, how and what we buy, reducing our waste, and changing how we use energy and water at home.

To help understand consumer engagement with the rapidly developing net zero agenda and associated approaches to climate change mitigation and adaptation, Consumer Scotland commissioned a consumer survey that would help identify consumer engagement and progress towards decarbonisation in Scotland. This report presents the key findings to emerge from the evidence we have collected.

The aim was to allow Consumer Scotland and key decision makers to appreciate the extent to which government policies and market progress are driving change and innovation in relevant consumer sectors. Where behavioural or policy gaps exist, these can be identified and recommendations made on how gaps in coverage can be filled or additional interventions proposed to help make further progress.

Our research

In late 2022/early 2023 Consumer Scotland commissioned an online survey with adults (aged 16+) resident in Scotland. Our research also sought to understand how consumers are responding to decarbonisation, their hopes for the future, the opportunities available, and the barriers they might face in relation to:

- reaching net zero

- the supply of energy and use in the home

- water supply and its use in the home

- general consumer markets, with a focus on household goods, transportation, parcel deliveries, food and drink, and recreation, primarily holidays for leisure

The aim of our research was to complement existing evidence on consumer attitudes and behaviours to decarbonisation in Scotland by establishing a baseline measurement against which Consumer Scotland could begin to track consumer engagement with and progress towards decarbonisation.

The project was delivered across two workstreams. Workstream 1 comprised a representative survey on energy and water topics, with fieldwork taking place between 24–28 February 2023. A total of 2,269 completed responses were achieved. Workstream 2 comprised a representative pilot survey covering general consumer markets. Fieldwork took place between 7–9 March 2023, with a total of 622 completed responses achieved.

Key points

- Most consumers in Scotland (77%) are concerned about climate change, with one in five (21%) stating they are unconcerned, and fewer than one in 10 (9%) stating they are not at all concerned

- A third of consumers agree (34%) they know what they need to do to help Scotland reach net zero, a third disagree (33%), and a further third (34%) state they are unsure

- Consumers rank the Scottish and UK governments and businesses as having most responsibility for reducing emissions, followed by organisations that regulate markets. Consumers are ranked as having least responsibility

- Consumers rely mostly on news media and local/national government for information about services. Almost a third (31%) of energy consumers look mostly to the news media for information. Around a quarter (24%) of water consumers look mostly to local authorities for information

- For ‘big ticket’ technological items in the energy sector that are more expensive to purchase or install (such as zero emissions heating systems or purchasing electric vehicles) consumers perceive cost as the single biggest barrier. Around two thirds (66%) of respondents agree renewable technologies are more expensive to install, with only 4% disagreeing

- For the minority of energy consumers not already doing simple low cost measures (such as switching off lights or turning down thermostats) these actions are perceived as being ineffective in reducing the environmental impact, or can be viewed as inconvenient or too much hassle

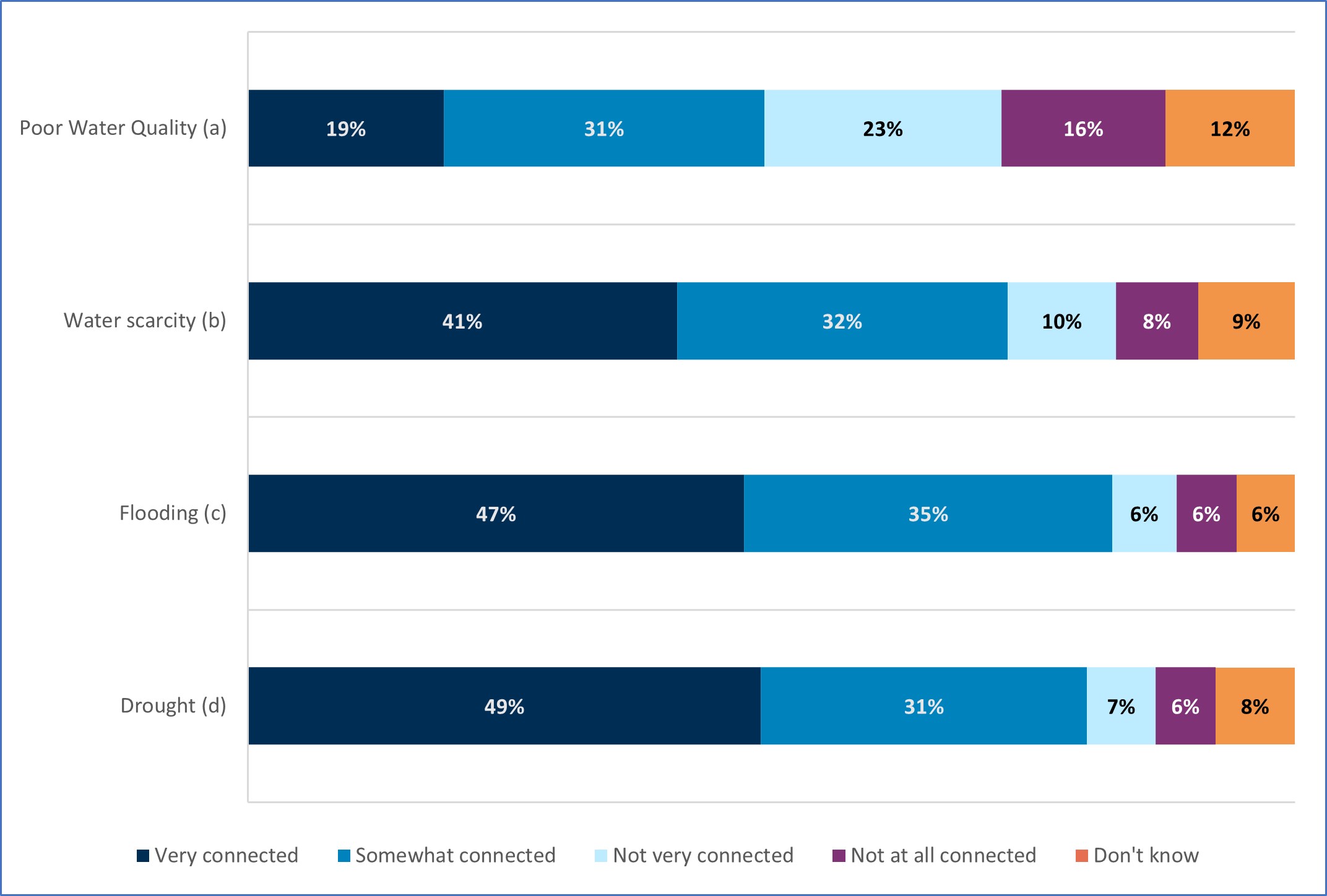

- There are high levels of consumer awareness of water-related effects of climate change: 80% believe drought is connected to climate change; 82% believe flooding is connected; 73% believe water scarcity is connected; and 50% believe poor water quality is connected

- The convenience and hassle factor are a significant barrier perceived by consumers in relation to water efficiency behaviours. Using a watering can was seen as being too much hassle by 58% of respondents and wiping or scraping cooking pans was seen as too much hassle by 53%

- A dominant perception persists amongst consumers that many water saving behaviours might be ineffective in reducing the environmental impact

- Across the general consumer markets we looked at (household goods, transportation, parcel deliveries, food and drink, and recreation/holidays), our results suggest that many of the more sustainable behaviours and choices being presented to consumers can appear as optional or are perceived as only having a limited impact on the environment or tackling climate change

- A lack of reliable trustworthy information is making it difficult for many consumers across all of the markets we looked at to fully understand the issues and from there make informed choices that lead to changed behaviour

Next steps

Many consumers in Scotland are concerned about climate change, but many report that they are already doing what they can to help tackle the problem, or they do not know what they need to be doing to help Scotland achieve net zero or to adapt to unavoidable climate change impacts.

Consumers look to governments, businesses and regulators to provide the leadership, guidance and solutions for tackling climate change. The result is that many consumers do not see themselves as a central part of the current narrative around adapting to a changing climate or the transition to net zero.

The barriers consumers report they face in relation to decarbonisation and the transition to net zero vary depending on the sector and/or the particular set of behaviours being asked about. But across markets it is clear a lack of reliable information is making it difficult for consumers to fully understand the issues and as a result make informed choices.

For many consumers sustainable behaviours are viewed as either unaffordable or niche, so they can lack widespread appeal. More work is required therefore on making sure the more sustainable alternatives are both affordable and accessible. Only then will they compete with the less sustainable – but more familiar – options that dominate current behaviours and practices.

A persistent difficulty if net zero ambitions are to be achieved will be changing consumers’ habits and engrained behaviours, particularly when it comes to doing anything that appears to be a hassle or is inconvenient. Given the scale of the challenge and the significant costs attached with some options that are being put forward as part of the solution, this will be especially difficult to overcome.

Our research was designed to help Consumer Scotland establish a baseline in our understanding of where consumers currently are at in terms of decarbonisation and the transition to net zero. Future iterations of our surveys will allow us track on an ongoing basis the extent to which consumers in Scotland are engaged in the transition to net zero so that we can recommend to government where policy gaps may exist or where support may need to be provided or enhanced.

To help complete the picture and further enhance our understanding, Consumer Scotland plans to commission follow up qualitative research in 2023/2024 that will explore our survey results further by examining in more detail consumers’ motivations, values, and social norms and how these intersect with the real and perceived barriers consumers face.

3. Introduction

The Scottish and UK governments have both made commitments to achieving net zero emissions. This means that by 2045 in Scotland and 2050 in the rest of the UK, we will no longer be adding to the total amount of greenhouse gases (GHG) in the atmosphere, which increase global temperatures by trapping the sun's energy (Energy Saving Trust, 2021).

Examples of GHGs are carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide. Carbon dioxide is released when oil, gas and coal are burned in homes, factories and to power transport, methane is produced through farming and landfill, and nitrous oxide is produced in the production of food and soil fertilisers. Examples of other impacts include those on product availability, the use of building materials, and growing cotton for clothing.

For the transition to net zero to be a success all sectors will be required to play their part in tackling climate change. For consumers this will involve changes to how most of us travel, what we buy, reducing our waste and changing how we use energy and water at home. This will require widespread changes to how we will go about our daily lives and how businesses will conduct their day to day activities.

For consumers to be at the centre of the transition to net zero should enable them to fully participate on an equitable basis by being provided with more sustainable and zero carbon alternatives as the most polluting technologies and practices are phased out. This will also involve the right support being provided in the right way so that all consumers are able to make the wide-ranging changes required to homes, lifestyles, transportation, and business practices. It should be noted, however, that progress in reducing emissions in Scotland has stalled in recent years, with the risk that interim and longer term targets are unlikely to be met without significant change.

To inform understanding of consumer engagement with the rapidly developing net zero agenda and associated approaches to climate change mitigation and adaptation, Consumer Scotland commissioned a new consumer survey in late 2022 and early 2023 that would help identify consumer engagement in and progress towards decarbonisation in Scotland.

This report presents the key findings to emerge from the evidence we have collected. The intention behind our research was to provide insight on where consumers currently are in relation to net zero and associated approaches to climate change mitigation and adaptation. In recent years the nature of the climate change debate has moved from asking if changes are required to how we go about our daily lives, to now being about how those changes should be undertaken. As a result, monitoring consumer participation in the transition is a priority for Consumer Scotland.

Understanding the issues in this report will allow Consumer Scotland and key decision makers to appreciate the extent to which government policies and market-driven shifts are driving change and innovation in relevant sectors. Where behavioural or policy gaps exist, these can be identified and recommendations made on how gaps in coverage can be filled or additional interventions proposed to help make further progress.

Any reluctance by consumers and businesses to change from current behaviours that are carbon intensive will be a key risk to meeting statutory emission reduction targets, as well as having a negative impact on current and future consumers. It is essential therefore that we are able to identify consumer views on efforts to decarbonise Scotland’s economy and other everyday practices. This will also allow us to identify the help and support consumers may require if they are to fully participate so that the transition is successful and no one is left behind.

The research this report is based on sought to understand how consumers respond to decarbonisation, their hopes for the future, the opportunities available, and the barriers they might face. The key issues Consumer Scotland wanted to gain insight on included:

- Consumer understanding and awareness of key terminology and language used in the transition to net zero

- The behaviours and practices that consumers are currently engaged in and those that they are not doing

- How invested consumers are in decarbonisation, in terms of understanding, attitude and action

- The barriers and opportunities that exist in relation to consumer participation in decarbonisation

- Consumer views on policies and drivers which will enable behavioural change and Scotland’s net zero targets to be met

- The source and types of information consumers require that they view as trustworthy and reliable to enable action

- How consumers can be motivated to engage in decarbonisation

The report is structured as follows. In the next chapter the background and context are outlined, with a particular focus on climate change as a global problem, recent policy responses in the UK and Scotland, and Scottish public opinion on climate change. This is followed by a discussion of the key methodological features of the research, which includes the approach taken to analysis and reporting. The main findings are presented in four standalone chapters related to: reaching net zero; energy supply and use in the home; water supply and use in the home; and general consumer markets, with a particular focus on: household goods, transportation, parcel deliveries, food and drink, and recreation with a specific focus on holidays for leisure.

The findings are brought together in a concluding discussion, which highlights key implications of the research. The report ends with an overview of next steps and where Consumer Scotland plans to go next with our research.

4. Background and context

Climate change as a global problem

Climate change has been identified by the United Nations (no date) as the defining issue of our time. On this basis humanity is at a critical moment for agreeing and implementing the actions that will be required to tackle the problems associated with a heating planet, and adapting to those unavoidable changes that are already being experienced globally.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recently reported that the difference between 1.5°C and 2°C of global warming presents significant risks to natural and human systems (IPCC, no date). However, unless emissions are reduced rapidly, the world is likely to exceed 2°C of warming, with a real possibility of reaching - or even exceeding - warming in excess of 4°C by the end of this century. In this scenario, the modelled data suggest catastrophic outcomes would be experienced globally.

The impacts of climate change are global in scope and unprecedented in scale. Rising sea levels and shifting weather patterns will lead to water scarcity, flooding, seasonality changes, heat stress, and damage to infrastructure, disrupting travel and food production and availability, among others. While the extent of risks will vary around the world, climate change has been marked out as a global justice issue (Klinsky, 2021). This creates a moral duty on the most polluting nations to take a lead in both reducing their own emissions as well as coming up with solutions that work for everybody on an equitable basis. Indeed, the Scottish Human Rights Commission (2023) has been working with the Scottish Government, Scottish Parliament and civil society to encourage the development of a human rights-based approach to securing climate justice.

In the lead up to the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow from 31st October – 13th November 2021, it was made clear that the level of dangerous climate change the world will experience will depend on how quickly we are able to reduce emissions being released into the atmosphere (McGrath, 2022). Importantly, however, even if all emissions were stopped today, it would likely not be enough to prevent some changes already taking place. Therefore, the sooner emissions are cut the smaller negative changes will likely be.

Climate change policy at the UK level

The UK’s Met Office (2021) has predicted that we will see winters that are warmer and wetter and summers that are hotter and drier, with more frequent and intense weather extremes experienced in unpredictable ways. With warmer air holding more water, average rainfall is increasing in the UK and around the world. In some places, increased rainfall is becoming more intense, and in other areas less rain is falling due to changes in wind patterns.

The UK’s ten warmest years on record have all occurred since 2002. Modelling in 2018 by the Met Office (2018) estimated that heatwaves are now 30 times more likely to happen in the UK than would have been the case without climate change. By 2050, it is predicted that heatwaves (like that seen in 2018) will likely happen every other year. In addition, although cold or dry winters will still occur, UK winters will likely become warmer and wetter on average, with a range of impacts on the natural and built environment.

The economics of acting on climate change have been well understood ever since the Stern Review in the mid-2000s which concluded that the “the benefits of strong and early action far outweigh the economic costs of not acting” (Stern, 2006: vi). As a result, there is now political consensus that without strong and drastic action on an unprecedented scale being taken, it will not only become more difficult over time to tackle climate change, but also more costly for both current and future generations.

As scientific, economic and political concern about climate change has increased in the UK, the Climate Change Committee (CCC) was established under the UK Climate Change Act 2008 as an independent statutory body. Its purpose is to advise the UK and devolved governments on emissions targets and to report to parliaments on progress made in the UK and its constituent parts in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and preparing for and adapting to unavoidable impacts of climate change.

In 2019 the UK was one of the first major global economies to pass laws aimed at ending its contribution to climate change by 2050 (HM Government, 2019). The target required the UK to bring all greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050, compared with a previous target of at least 80% reduction from 1990 levels.

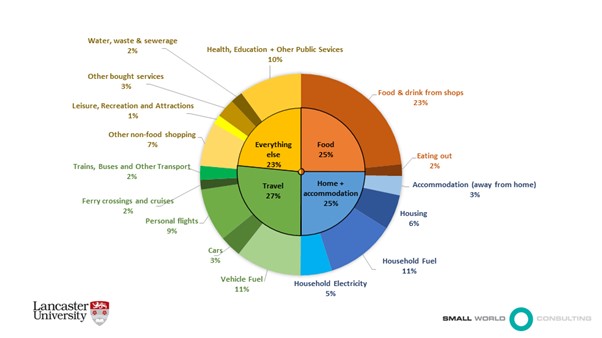

Figure 1 summarises the carbon footprint by source of a typical UK person. This was presented by Mike Berners-Lee (2020) to the UK Climate Change Assembly.

Figure 1: Average UK person’s Greenhouse Gas footprint: 12.7 tonnes CO2e per year

The main components of an average UK person’s carbon footprint: at home it is domestic energy use; for travel it is car travel and flights; for food it is food and drink from shops; and for everything else it is the use of public services, such as health and education (reproduced from Berners-Lee, 2020).

Berners-Lee calculated that in 2020, the average annual carbon footprint was 12.7 tonnes carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) per person per year. This estimate was calculated just before the pandemic, with Covid-19 lockdowns leading to a significant drop in emissions before gradually rising again (Roy, 2022). Figure 1 is significant for highlighting the context within which emission reduction targets operate. The main components of an average UK person’s carbon footprint at home are domestic energy use, for travel it is car travel and flights, for food it is food and drink from shops, and for everything else the main components are use of public services, such as health and education.

It should be noted that different footprint calculators will give different results depending on the underlying assumptions, sources of data, and what they include or exclude. The Berners-Lee calculator attempts to be comprehensive by including the effects of income, goods and services consumption and infrastructure emissions as well as the usual energy, food and transport footprints. Nevertheless, we should treat these sorts of calculator with caution and useful in so far as they provide a quick and easy to use way of exploring options on how individuals can reduce their emissions footprint.

The CCC published its Sixth Carbon Budget report in December 2020 (CCC, 2020a). This was based on an extensive programme of analysis and consultation and resulted in a recommended pathway that would require a 78% reduction in UK territorial emissions between 1990 and 2035. In effect, this would bring forward the UK’s previous 80% target by nearly 15 years. The CCC set out in four key steps how the Sixth Carbon Budget can be met:

- Take up of low carbon solutions

- Expansion of low carbon energy supplies

- Reducing demand for carbon intensive activities

- Land and greenhouse gas removals

In 2021 the UK Government published its Net Zero Strategy, setting out a pathway for reaching net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 (HM Government, 2021). However, more recently the economic outlook in the UK has changed considerably as a result of the UK’s exit from the European Union driving up prices, a protracted recovery period following the Covid-19 pandemic, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine driving up the costs of wholesale energy. These additional pressures on households and businesses have been experienced as excessively high energy prices and wider inflationary pressures.

Given the changed economic context, the UK Government commissioned a review into its approach to net zero. The review set out to better understand the impact of the different ways to deliver its net zero pathway on the UK public and economy and to maximise economic opportunities of the transition, such as improved public health outcomes or further economic growth in relevant sectors. Chris Skidmore MP was appointed by the then Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Secretary of State as chairperson to review the approach being taken to net zero in the UK with a view to ensuring that delivering the net zero target did not place undue burdens on businesses or consumers (Skidmore, 2021).

The net zero review considered the potential exposure of businesses and households to the transition, and highlighted factors to be taken into account when designing decarbonisation policy that will allocate costs over this time horizon, so that the policy can help to make the most of opportunities that will arise, and support households as necessary. In doing so it made 129 recommendations, covering areas including the greater role that business can be supported to play, making better use of infrastructure and delivering more energy efficient homes.

In response to the Skidmore Review, as well as a High Court ruling in July 2022 that the UK Government’s current plan for achieving net zero was not detailed enough to show how the UK would meet its goal to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050 (Gayle, 2022), a series of policy papers were published by the UK Government under the overarching title of ‘Powering Up Britain’ (HM Government, 2023). These papers set out the government’s preferred approach for the UK’s energy security and net zero commitments to be met, in a way that would aim to maximise the economic opportunities of the transition. The priority for the UK Government was to create the right conditions so that the UK’s energy security was enhanced in a way that would also ensure the economic opportunities of the transition to net zero could be realised and the government’s net zero commitments achieved.

Central to the UK Government’s strategy is the storage of CO2 under the North Sea using Carbon Capture Storage, which UK Ministers have stated also aims to lower energy bills (Stallard, 2023). Although carbon capture has been recommended by the UK’s CCC as a way to remove carbon dioxide already in the atmosphere, concern has been expressed that it could allow the UK to keep using oil and gas rather than focusing on renewable energy or reducing demand. Heating in homes currently accounts for around 14% of UK emissions. However, though it is one of the most effective ways to bring down energy consumption for heating and therefore emissions, there has been no significant increase in funding from the UK Government for home insulation.

In a report co-produced by the Intergenerational Foundation and the Social Market Foundation, key economic and moral questions surrounding how to share the costs between generations of the transition to net zero were considered (Anderson-Samways and Hobby, 2022). A range of factors were identified in the paper, each noted as playing a role in shaping policymaking decisions on how much should be spent on the transition to net zero:

- Moral attitudes to future generations

- Prospects for future economic growth

- Attitudes to inequality between and within generations

- Attitudes to risk

The report makes the case that these considerations are not just economic ones, but also moral and ethical ones that should be decided by open dialogue within society and not simply left to policymakers. The report concluded that, in the interests of intergenerational fairness, the UK Government should commit to spending significantly more at present in order to reach net zero commitments. Singling out the “polluter pays” principle, this investment should be primarily financed by increasing the carbon price in the UK Emissions Trading Scheme and carbon taxation today, rather than borrowing from future generations.

Climate change policy in Scotland

Scotland is playing its part in the global effort to tackle climate change by recognising that all of our homes, businesses and communities will need to be using less energy and water, using different sources of energy, and reducing consumer participation in the full range of carbon intensive activities whose exponential growth we have long become accustomed to. It will also require our cities, towns and villages to become more resilient when unexpected and unpredictable weather events occur.

Scotland’s emissions reduction targets were first set out in the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 (Scottish Parliament, 2009). This created the statutory framework for greenhouse gas emissions reductions in Scotland. The 2009 Act was later amended by the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019 (Scottish Parliament, 2019). This significantly increased the ambition of Scotland’s emissions reduction targets, setting a target to be net zero by 2045. This renewed target was ahead of many other countries at the time, including the UK, where the target set was to reach net zero by 2050 (HM Government, 2021).

In passing the 2019 legislation the Scottish Parliament also set new statutory interim targets: 56% reduction by 2020; 75% reduction by 2030; and 90% reduction by 204 These interim targets were relative to 1990 levels of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide and 1995 levels of hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons, sulphur hexafluoride and nitrogen trifluoride. To help ensure delivery of the long-term targets, the framework also included statutory annual targets for every year to net zero.

However, despite the Scottish Government stating its ambition to reduce emissions, the UK CCC has remained concerned that “underlying progress in reducing emissions in Scotland has largely stalled in recent years. Since the Scottish Climate Change Act became law in 2009, the Scottish Government has failed to achieve 7 of the 11 legal targets” (CCC, 2022c).

To support delivery of Scotland’s targets, the Scottish Government publishes a statutory strategic delivery plan every 5 years. The updated Climate Change Plan (CPP) in December 2020 responded to the Scottish Government’s declaration of a climate emergency in 2019 (Scottish Government, 2019). The updated CPP set out a pathway for the economy and society for Scotland’s emissions reduction targets to be met over the period to 2032 (Scottish Government, 2020a).

However, the CCC has noted that, in its view, Scotland’s legislated 2030 interim target of a 75% reduction in Scottish emissions goes beyond the level of any of the CCC’s five scenarios on the path to net zero set out in the Sixth Carbon Budget (CCC, 2020b). Their analysis indicates that meeting the statutory 2030 target will be extremely challenging. However, while the CCC has expressed concern, they have not gone as far to recommend that the target should be changed in law and instead focus on encouraging delivery of appropriate policy levers.

Importantly all of Scotland’s statutory targets are economy wide. They include all territorial greenhouse gas emissions as well as an estimated fair share of emissions from international aviation and shipping and territorial removals, including from the land use sectors. The statutory framework used by the Scottish Government for Scotland’s emissions reduction activities sets out a default position that Scotland’s targets will be met only through domestic action, without the use of international offset credits.

The Scottish Government believes that Scotland becoming a net zero nation will benefit the environment, people, and society by transforming Scotland’s economy, environment, and communities. Our energy sources will be more sustainable, our buildings more energy efficient, how we travel will be cleaner, our diets healthier, and the natural environment will recover.

However, achieving targets will not be straightforward, nor easy, but it will affect us all. As the Scottish Government has stated, it will need to be “a truly national endeavour with business, communities, and individuals contributing fully. It will require us to be innovative, utilising new and exciting technologies and learning by doing” (Scottish Government, no date (a)). Achieving this will require the whole of Scotland taking action to reduce emissions, at the same time as adapting and building resilience to those impacts of climate change that are unavoidable.

However, to meet targets, a rapid transformation across all sectors of economy and society will be required. Box 1 summarises just some of the steps some utility network providers plan to take in the transition to net zero.

|

Box 1 – Utility networks plans towards net zero Water supply and waste water services – Scottish Water (n.d.) responded to Scotland’s statutory target by committing to being net zero of emissions by 2040, five years earlier than the national target. This target includes both embedded carbon and carbon emitted from day-to-day operations. To be achieved, however, Scottish Water has recognised this will require Scottish Water undergoing a sweeping transformation over the next 25 years. Energy distribution – Ofgem (n.d.) sets price controls for the gas and electricity network companies in Great Britain. These controls balance the relationship between investment in the network, company returns and the amount that they charge for operating their respective networks. RIIO-2 was the second set of price controls implemented under our RIIO model. It's an investment programme to transform the energy networks and the electricity system operator to deliver emissions-free green energy in GB, along with world-class service and reliability. Telecommunications – As a sector telecoms has been on its own journey to net zero. As an example, BT Group (2021) announced in 2021 they were planning on building on significant progress in reducing their emissions by bringing forward their target for achieving net zero from 2045 to 2030 for their own operational emissions, with their supply chain and customer emissions following in 2040. |

Without doubt achieving annual emissions reductions has proven challenging, however much progress has been made. Despite this the CCC has been clear that there is a need for the Scottish Government to urgently provide a quantified plan for how its polices will combine and interact with the UK Government’s separate plans to achieve emissions reductions. The CCC noted that progress was starting to fall behind the levels required to meet legally binding targets and that progress towards adapting to the impact of climate change had stalled (CCC, 2022a).

Becoming a net zero nation also presents as a moment of opportunity for Scotland as a whole by transforming Scotland’s economy, environment, and communities. The 2019 Act embedded the principle of a just transition, where reducing emissions is done in a way that tackles inequality and promotes fair work. Central to this will be effective engagement with the people living in Scotland, which the Scottish Government believes marks a new chapter in a “people-centred approach to climate change policy” that is different from anything that has come before (Scottish Government, no date (b)).

It also led to the publication of the Scottish Government’s ‘Net Zero Nation: public engagement strategy’ (2021b), which set out an overarching framework for engaging the people of Scotland in the transition to a net zero nation so that everyone is prepared for the effects of a changing climate by ensuring the people of “Scotland recognises the implications of the global climate emergency, fully understands and contributes to Scotland’s response, and embraces their role in the transition to a net zero and climate ready Scotland” (p.7).

The costs of the transition to net zero will be significant, but the potential benefits substantial. The Scottish Government has estimated that undertaking energy efficiency upgrades and installing low carbon heating systems in homes could cost around £33 billion over the period to 2045 (Scottish Government, 2021c).However, consumers and businesses across the UK are facing significant financial pressures due to high inflation and declining real disposable household incomes. This holds the potential to lead to increased likelihood of vulnerability being experienced by a wider range of consumers in Scotland. As a result, to be a success, the transition to net zero will require financial incentives and dedicated support for many consumers, including small and medium sized businesses.

Despite the significant cost, the transition to net zero also creates opportunities, such as encouraging sustainable economic growth, improved employment opportunities, and better housing conditions leading to enhanced health and wellbeing among the population. A policy briefing by the Centre for Energy Policy at the University of Strathclyde concluded that real household income gains resulting from reduced energy bills could lead to sustained economic expansion due to the level of disposable income increasing, which would be available to spend elsewhere in the economy (Katris et al, 2021).

In responding to the Just Transition Commission’s report recommendations, the Scottish Government committed in the draft 2023-2024 Scottish Budget to delivering an enhanced package of policies to be set out in an updated Climate Change Plan and a new Energy Strategy and Just Transition Plan by the end of 2023 (Scottish Government, 2022a). Together these documents set out the actions required to deliver a net zero energy system that supplies affordable, resilient and clean energy to Scotland’s workers, households, communities and businesses. The CCC has welcomed the Scottish Government’s focus on a just transition based on fairness, however it raised concerns about the lack of a clear delivery plan on how targets will be achieved (CCC, 2022a).

Finally, it should be noted that a range of other relevant policy and legislative developments in Scotland are upcoming that will shape the nature of climate change policy in Scotland for some time to come. These include a new Climate Change Plan for Scotland, a Circular Economy Bill and Route Map to deliver a circular economy; an updated Climate Emergency Skills Action Plan; and new public engagement strategies for climate change and heat in buildings.

Scottish public opinion on climate change

In terms of public opinion on climate change, we know from the 2021 Scottish Household Survey (SHS) that there has been an increase in the proportion of adults in Scotland viewing climate change as an immediate and urgent problem, rising from 80% in 2020 to 83% in 2021 (Scottish Government, 2023). While comparisons across multiple years of the SHS is not possible due to changes in methodology, increases in concern about climate change amongst the adult population has been steadily increasing over time. Notably, in 2021 the largest increase was seen was amongst those aged 75+, increasing from 69% in 2020 to 76% in 2021. However, this is still lower than the results for all other age groups which range from 82% to 86%.

In November 2022, the Scottish Government published the results of a representative survey with the Scottish public, focused on attitudes and engagement with climate change. The results were intended to act as a baseline for a forthcoming public engagement strategy for climate change. These results indicated that while concern about climate change is not the most important policy issue for the Scottish population, it is one of the top 3 issues. The Scottish public are more likely to rank the economy (24%) and health and social care (24%) as the policy issues that are most important to them, with climate change being ranked third, being selected as the top issue by 15% of the population.

The same Scottish Government survey indicated the extent of the Scottish population’s knowledge about climate change. Over half (58%) of respondents stated that they know at least "a fair amount" about climate change. However only around one in ten (12%) are confident enough to say that they know "a lot" about it. Just 4% say they don't know anything about it. In this survey those respondents aged 18-34 were significantly more likely than older respondents to say that they know a lot or a fair amount about climate change. School aged young people (aged 14-17) included in the survey were more in line with the Scottish average.

It is also worth noting however previous research for the Postcode Lottery on consumer attitudes to sustainable lifestyles and the environment highlighted a tendency for individuals to overestimate the impact of day-to-day behaviours (such as recycling or active travel) and to underestimate the relative impacts of larger, high-impact lifestyle shifts (such as switching to an electric vehicle, flying less often, or cutting down on consuming meat and/or dairy) (The Diffley Partnership, 2021).

It is clear therefore that any reluctance by consumers and businesses to change from current carbon intensive behaviours will be a key risk to Scotland meeting its statutory emission reduction targets, as well as having a negative impact on current and future consumers. It is essential therefore that Consumer Scotland and other key decision makers are able to identify where consumers currently are at in terms of the transition to net zero and efforts to decarbonise Scotland’s economy and other social practices. Only then will we be able to identify the help and support that they may require if they are to fully participate on an equitable basis, ensuring that the transition is a success where no one is left behind.

5. Methodology

In late 2022/early 2023, Consumer Scotland commissioned The Diffley Partnership research agency to conduct an online survey with adults (aged 16+) resident in Scotland. The aim of the survey was to complement existing evidence on consumer attitudes to decarbonisation by establishing a baseline measurement against which Consumer Scotland would be able to track consumer engagement with and progress towards decarbonisation.

The project was delivered as two distinct workstreams:

• Workstream 1 – Development of a new quantitative questionnaire and associated fieldwork that covered decarbonisation attitudes, behaviours, and intentions of the public in the energy and water sectors

• Workstream 2 – Development and piloting of a new quantitative questionnaire covering decarbonisation attitudes, behaviours, and intentions of the public in other consumer markets of interest to Consumer Scotland: household goods, transportation, parcel deliveries, food and drink, and recreation, with a focus on holidays for leisure

To develop the Workstream 1 questionnaire previous surveys undertaken by the Consumer Council for Northern Ireland (CCNI) and the Consumer Council for Water (CCW) were consulted to help identify appropriate topics and questions. To support development of the Workstream 2 pilot questionnaire, a rapid evidence review was undertaken by the research agency to further understand the policy context and potential evidence gaps. The aim was to help determine the sectors and sub-topics to include in the Workstream 2 pilot survey covering a number of wider general consumer markets of interest to Consumer Scotland. The questionnaires for both workstreams are shown in the appendices to this report.

The surveys for both workstreams were administered through the ScotPulse online panel of over 42,000 adults (aged 16+) resident in Scotland. Panel members sign up on a voluntary basis and are not paid to complete surveys. The panel is recruited through a range of advertising, including advertising on national television as well as on social media profiles. Panel participants are chosen at random to take part in the surveys.

The survey fieldwork for Workstream 1 took place between 24th and 28th February 2023 with a total of 2,269 completed responses achieved. The pilot survey fieldwork for Workstream 2 took place between 7th and 9th March 2023 with a total of 622 completed responses achieved.

Summaries of the profile of the survey respondents across a number of key demographic variables appear in Table 1. This includes the weighted sample sizes achieved for each category. For both workstreams the survey data was weighted by the panel manager to the age and gender profile of the population in Scotland using mid-year population estimates.

Table 1: Demographic profile of the survey respondents in Workstreams 1 and 2

| Demographic category | Workstream 1 weighted sample size |

Workstream 2 weighted sample size |

| Gender Male Female |

2,269 1,094 1,175 |

622 300 322 |

| Age band 16-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65+ |

2,269 656 338 372 374 529 |

621 179 93 102 103 144 |

| Number of people in household 1 person 2 people 3 people 4+ people |

2,269 367 1,001 451 451 |

622 113 274 125 111 |

| Presence of children Yes No |

2,269 496 1,773 |

622 143 479 |

|

Activities limited by health/disability Yes – limited a lot |

2,269 238 |

621 80 |

| Estimated annual household income before tax Under £15,000 £15,000-£29,999 £30,000-£49,999 £50,000-£74,999 £75,000-£99,999 £100,000+ DK/rather not say |

2,269 |

621 |

|

Working status Working full time Housewife* |

2,264 993

64 |

621 265

12 |

| Housing tenure Owns with mortgage or loan Owns outright Rent – social landlord Rent – private landlord Other arrangement Part own, part rent |

2,263 872 820 297 188 70 16 |

621 261 221 70 51 16 4 |

* Current variable name used by panel manager that is under review

Approach to analysis and reporting

The responses for both workstreams were tabulated by the research agency and analysed quantitatively. The analytical approach allowed the prevalence of views amongst respondents to be identified in addition to differences in opinion by key demographic variables. This report summarises key findings of both surveys and makes connections to the policy context to draw out noteworthy findings and between-groups differences.

Where percentages do not sum to 100%, this is due to rounding, the exclusion of ‘don’t know’ categories, or multiple answers being provided. Aggregate percentages (for example where ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ responses are combined and reported as net agree or

net disagree) have been calculated from the absolute values. Therefore, aggregate percentages may differ from the sum of individual scores due to rounding of percentage totals.

Significance testing and margin of error

Significance testing and margin of error both use a confidence interval (95% or 99%). These are complementary but look to measure difference aspects. A 95% confidence level in significance testing is standard practice in social research. This means that where significant differences are found, we’re at least 95% sure that these didn’t happen by chance. A 99% confidence level is typically used when measuring the margin of error and is calculated by using population estimates and sample sizes. This means that we are 99% sure that, given the sample size we have, the attitudes/behaviours for the full population lie within a range of percentage points (confidence intervals) above or below what was found in the survey.

In this research significance testing at a 95% confidence level (p < 0.05) was applied to determine between-groups differences in opinion. Differences are only reported in this report when statistically significant unless otherwise stated. The reporting does not

include every result of every statistical test conducted; only results identified as most relevant for this report are highlighted. The full data tables showing statistical significance are available on request.

The margin of error for the data, based on a nationally representative survey of the adult population of Scotland is 3% at the 99% confidence level. The margin of error refers to the range of values above and below the actual survey result that we can be sure the views of the public will lie between. For example, if 50% of the sample surveyed strongly agree with a statement, a 3% margin of error means that we can be sure that between 47% to 53% of the general population strongly agree with the same statement.

6. Reaching net zero

Consumers in Scotland are concerned about climate change

Our results indicate that most consumers in Scotland are concerned about climate change, with 77% of respondents net concerned compared to 21% net unconcerned. Fewer than one in ten respondents (9%) stating they are not at all concerned about climate change. These results point in the same direction as other survey evidence, including the Scottish Household Survey (SHS), where the proportion of adults in Scotland viewing climate change as an immediate and urgent problem has been reported to have risen from 80% in 2020 to 83% in 2021 (Scottish Government, 2023).

In terms of demographic differences, our survey results indicate that females are more likely (86%) to be net concerned about climate change than males (68%) and, as a result, males are more likely (32%) to be net unconcerned than females (12%). These results are also consistent with the SHS, where women were reported to be more likely than men to view climate change as an immediate and urgent problem, although the gap has narrowed: 84% compared to 82% in 2021 and 82% compared to 77% in 2020.

Our survey results also suggest that those in the ABC1 social grades categories are more likely (83%) to be net concerned about climate change than those in the C2DE social grades categories (70%), and subsequently, those in the C2DE social grades categories are more likely to be net unconcerned (27%) about climate change than those in the ABC1 social grades categories (17%).

Consumers self-report a lack knowledge about what they can do to help Scotland reach net zero

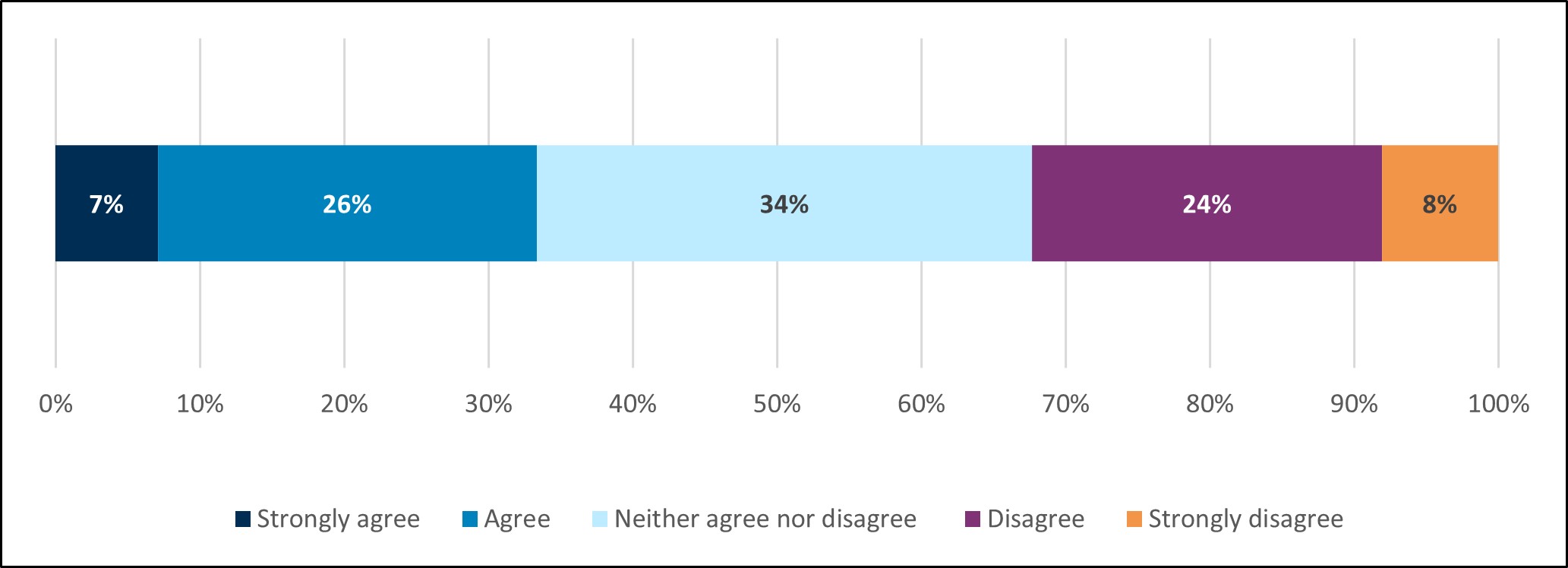

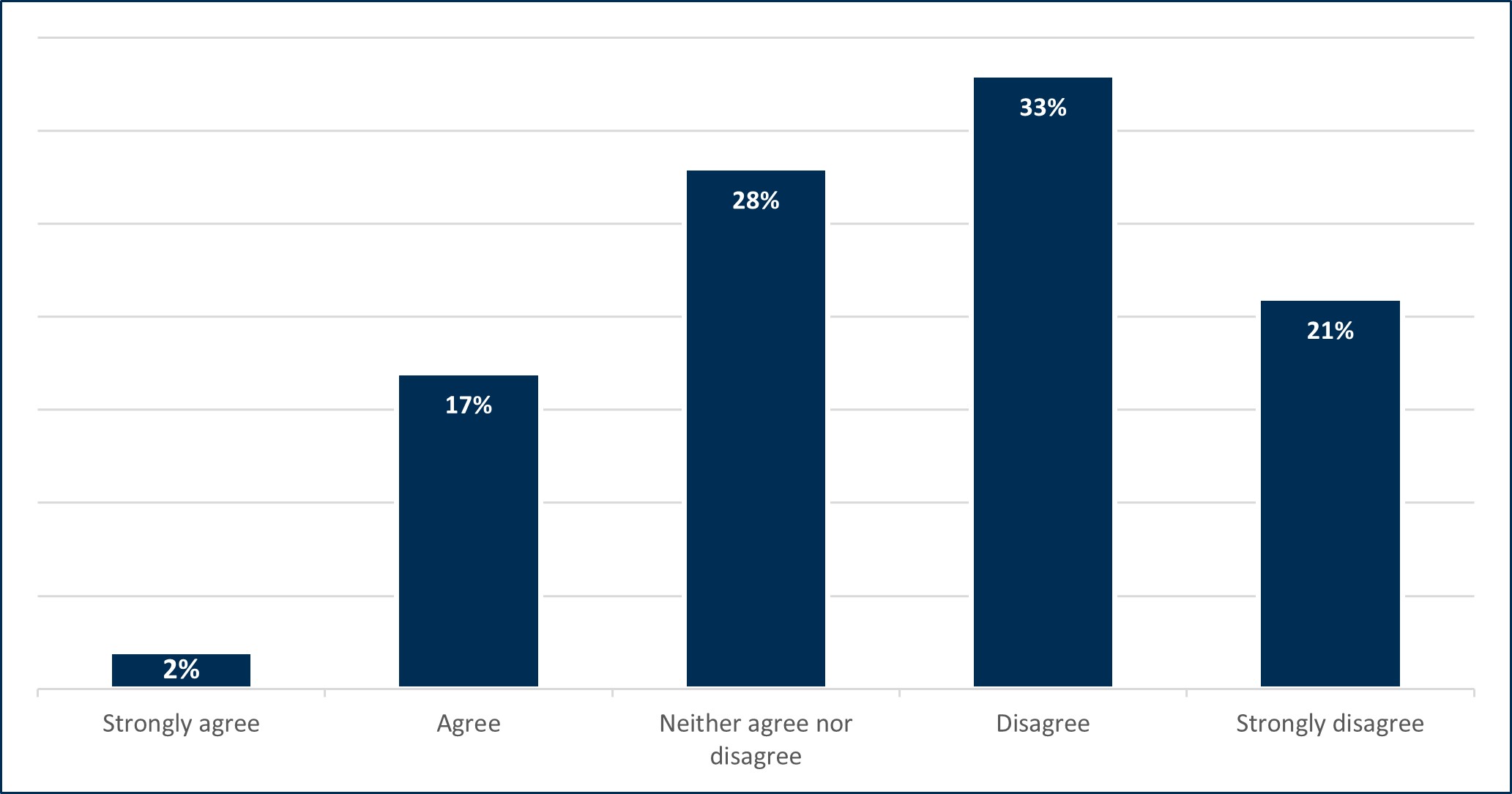

In our full sample survey, one third (34%) of respondents stated they net agree that they know what they need to be doing to help Scotland reach net zero (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Scotland's population are evenly split between agreeing, disagreeing or unsure they know what do to help Scotland reach net zero.

Proportion of respondents answering Strongly Agree, Agree, Neither Agree nor Disagree, Disagree or Strongly Disagree to the statement "I know what I need to do to help Scotland reach net zero by 2045".

Weighted base: 2,262

A further third (33%) of respondents stated they do not know what they need to do to help Scotland reach net zero, and a final third (34%) are unsure (neither agreeing nor disagreeing). This indicates that while Scotland appears to be in a good position from which

to build further support for action on climate change and engagement with decarbonisation and net zero policies, there is more work to be done in terms of the two thirds (67%) stating they do not know or are unsure what they need to do to help reach net zero.

The strongest demographic differences in our survey for this issue was by age group, with the oldest age group (aged 65+) being more likely (39%) to state they know what they need to be doing to help Scotland reach net zero, compared to 29% of those aged 16-34 years old

stating the same.

Our results are important because over 60% of the required emissions reductions to meet net zero will be “predicated on some kind of individual or societal behavioural change” (research by the CCC cited by Scottish Government, 2020a: 111). The Scottish Government’s overall approach is based on an assumption that higher impact emissions savings will need to come from behavioural changes, so increased public engagement on domestic emissions reductions will be fundamental to success. However, current levels of awareness of what is required are low, which sits alongside poor public understanding of the issues.

Consumers view governments and businesses as most responsible for reducing emissions

Respondents to our survey were asked to rank who they thought had most responsibility for reducing carbon emissions in the energy, water and other more general consumer markets. Across all of the sectors we were interested in exploring, respondents tended to rank the

Scottish and UK governments and the businesses delivering services within those markets as having most responsibility for reducing emissions, followed by organisations that regulate those markets.

Respondents ranked consumers as having least responsibility for reducing carbon emissions. Though it should be noted that this does not mean that consumers see themselves as not having any responsibility. Rather consumer responsibility is being ranked relatively lower

compared to other categories, such as governments, businesses and regulators.

This finding that consumers were ranked as having least responsibility for reducing carbon emissions across the sectors is an important one when viewed alongside the earlier finding that most people in Scotland view climate change as an important issue. This indicates that

it appears to be an issue where the role of consumers in tackling climate change is difficult to get across, which in turn may support the Scottish Government’s plans for an effective public engagement campaign that can help everyone understand their role if they are to play their part and help Scotland reach the goal of transitioning to net zero. Though this is unlikely to be sufficient on its own, with a mix of levers including incentives and regulation likely required.

Self-reported consumer awareness of how to save energy and water is high, but raising more awareness among the wider population is feasible

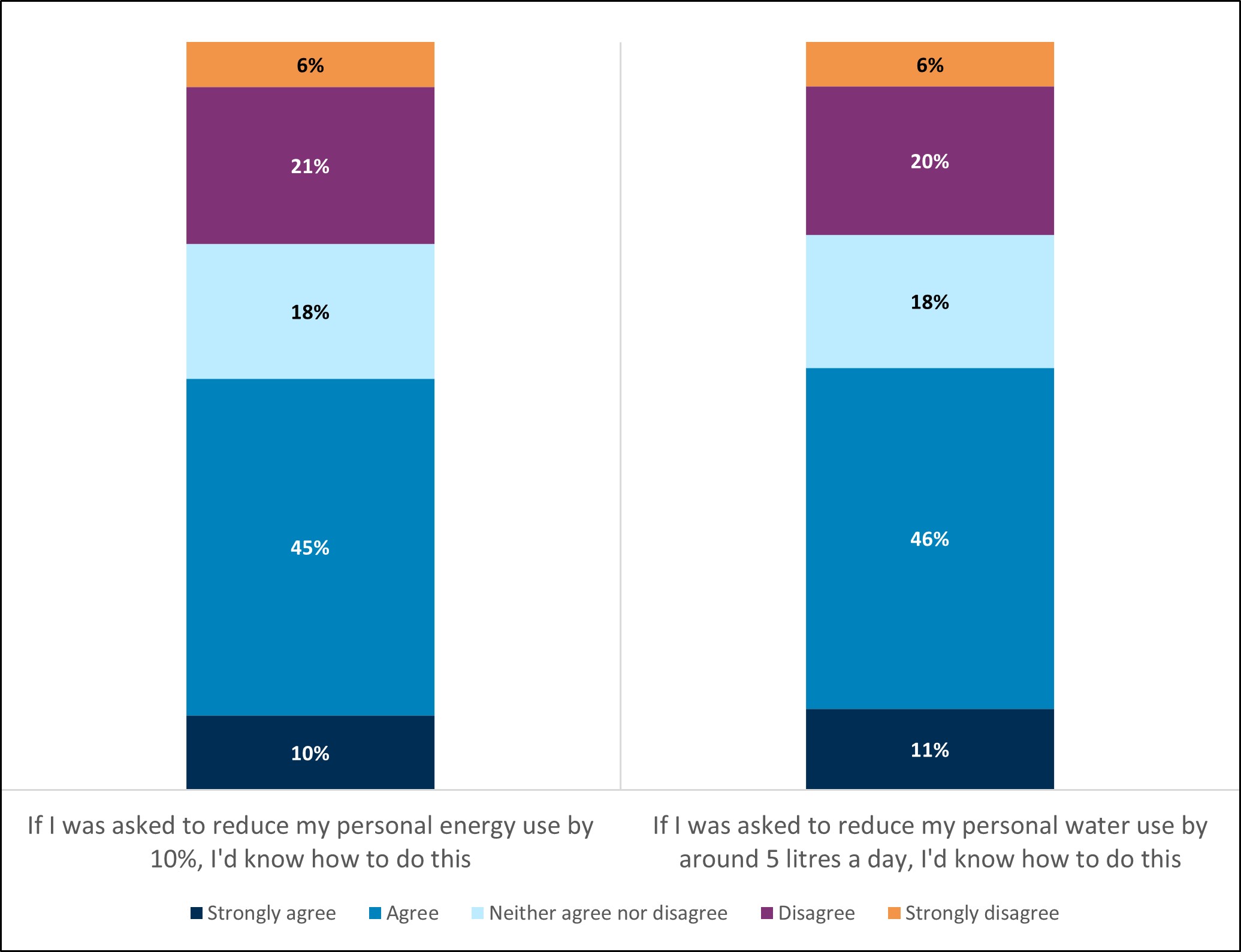

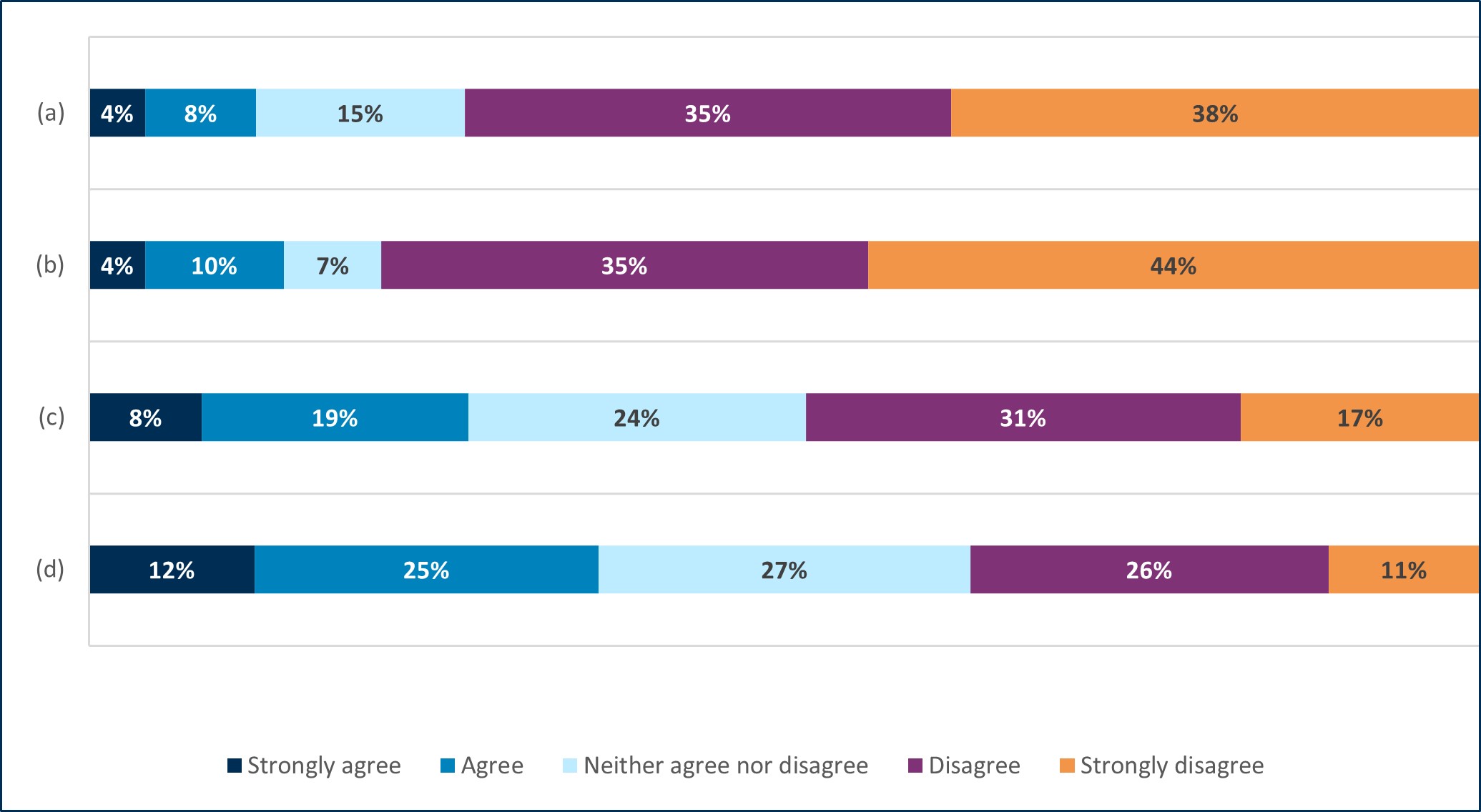

Our survey respondents were also asked to agree or disagree with two hypothetical statements about self-reported knowledge of how to reduce personal energy and personal water use in the home. The results are summarised in Figure 3.

Figure 3 - Most consumers state they would know how to save energy and water if asked to do so, but there is potential for more awareness raising among the wider population.

Proportion of respondents answering Strongly Agree, Agree, Neither Agree nor Disagree, Disagree or Strongly Disagree to two hypothetical statements.

Weighted base: 2,265

For the hypothetical energy question, the results show that over half (55%) of respondents net agreed that they would know how to reduce their personal energy use by 10% if they were asked to do so. Though it should be noted that there was a strong age effect in the data, with around two thirds (65%) of those aged 65+ stating they would know how to reduce their personal energy use by 10%, compared to well under half (43%) of those aged 16-34 stating the same.

For the hypothetical water question, the results show that 56% of respondents net agreed they would know how to reduce their personal water use by around five litres a day if they were asked to do so. This is broadly comparable with previous survey results published by

the Consumer Council for Water (CCW), where 57% of water consumers in England and Wales in 2022 net agreed with the same statement.

There was also a strong age effect for the hypothetical water question, with two thirds (63%) of respondents aged 65+ year olds stating they would know how to reduce their personal water use by around five litres a day, which was significantly more than those aged

16-34 years old (50%) and 35-44 years old (49%).

Energy and water consumers rely mostly on news media and local/national government for information

Successful engagement with the markets consumers are participating in largely hinges on the provision, appropriateness and adequacy of information that can be relied upon to provide the right information in the right format and at the right time. This is particularly

important for complex and emerging issues that may be unfamiliar to consumers.

Our survey results indicate the sources of information used by consumers in the energy and water markets and the extent to which that information is held to be trustworthy and helpful:

Energy: the most prominent source of information related to energy and its supply was from the news media (31%), followed by the Scottish Government (26%). Roughly similar proportions of respondents reported receiving information via the UK Government (16%), social media (15%) and local authorities (14%)

Water: the most prominent source of information related to water and its supply was from local authorities (24%), followed by the news media (22%), and the

Scottish Government (20%). Roughly similar proportions report receiving this information via public bodies (12%), which will include Scottish Water and relevant

regulators, and social media (11%)

Respondents were asked to rank whether information about energy and water supply and its use is trustworthy or helpful. Scientists were ranked as having the highest rates of trust and helpfulness in terms of energy, though only a minority of energy consumers are getting their information from this source. The news media was the most commonly reported source of information regarding energy supply and its use, with trust and helpfulness for this category being ranked around the midpoint. Among those who receive information about energy use from the Scottish Government, there were relatively high levels of trust and helpfulness being reported.

In terms of water, the minority of respondents who get their information from scientists reported this source as having a high rate of trust and helpfulness. Local authorities were the most reported source of information regarding water use in the home and those respondents who get information from this source tended to report a generally positive view in terms of trust and helpfulness. Among those who receive information from Scottish

Government about water use, there were also high levels of trust and helpfulness reported.

Our results on trust can be contrasted with the spring 2023 wave of the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero’s (DESNZ) Public Attitudes Tracker (DESNZ, 2023).

Respondents from across the UK as a whole were asked in that survey to rank levels of trust in summer 2022 in a range of sources of information about climate change, including:

- Newspapers or newspaper websites

- UK Government

- TV news (e.g. BBC, ITV, Sky)

- Scientists working at universities

- Social media (e.g. Facebook, Twitter)

- Scientific organisations (e.g. Royal Society, Met

- Office; TV/radio documentaries)

- Charities, environmental, campaign groups (e.g.

- Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth)

The highest levels of trust in information related to climate change were reported for scientists at universities (86% trusted, with 39% trusting them a great deal), scientific organisations (85% trusted, with 39% trusting them a great deal), and TV and radio

documentaries (74% trusted, with 12% trusting them a great deal). The sources of information most likely to be ranked as not being trusted were social media (77% not

trusted, with 41% not trusted at all), newspapers or newspaper websites (51% not trusted, with 16% not trusted at all), and the UK Government (47% not trusted, with 12% not trusted at all)

7. Energy supply and its use at home

Most consumers are concerned about their energy use at home

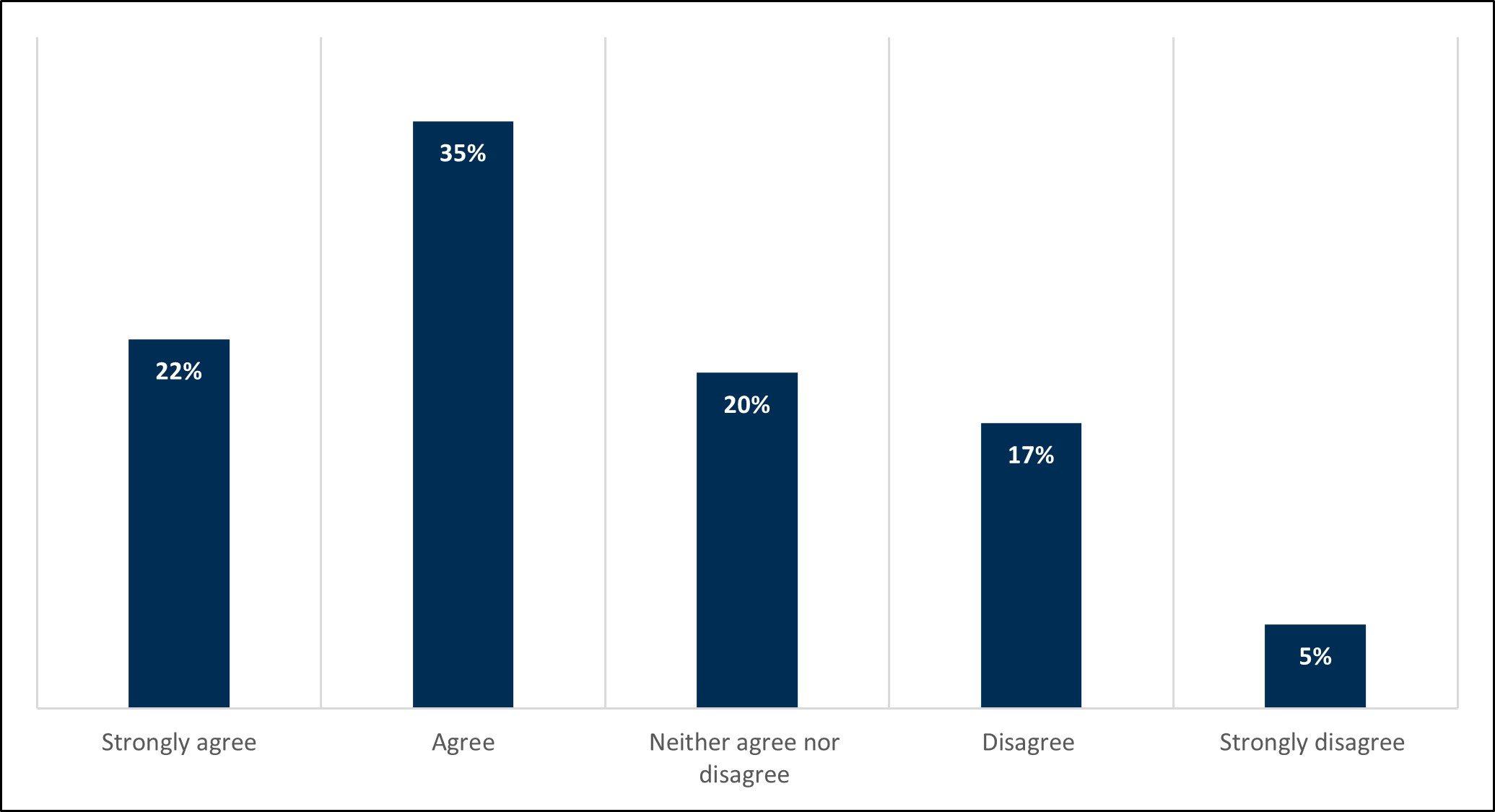

Our survey asked respondents the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the statement: “I’m concerned about how much energy is used in my home”. The results are summarised in Figure 4 and show that the majority of the respondents (58%) net agreed with the statement, but one in five (20%) neither agreed nor disagreed, with a similar proportion net disagreeing (22%).

Figure 4 - Most consumers in Scotland are concerned about how much energy is being used in their home.

Proportion of respondents answering Strongly Agree, Agree, Neither Agree nor Disagree, Disagree or Strongly

Disagree to the statement: "I’m concerned about how much energy is used in my home”.

Weighted base: 2,249

There was no statistically significant difference between income groups net agreeing with the statement, I’m concerned about how much energy is used in my home. However, those in the middle and highest income categories were significantly more likely than those on the lowest incomes (under £15,000) to net disagree with the statement: 25% of respondents with an income of £30,000-£49,999, 27% of respondents with an income of £50-£74,999, 25% of those on an income in excess of £100,000 compared to 15% of those with an income under £15,000.

While it is not possible to state definitively what the main concern here is primarily related to, we know from other evidence that consumers in Scotland continue to find meeting the high costs of energy challenging. In particular, the winter 2022 wave of Consumer Scotland’s

energy tracker showed that one-third of consumers report they are not managing their household finances well, which was consistent with the previous wave findings in autumn 2022 (Consumer Scotland, 2022). In the same winter 2022 wave of the energy tracker, 68%

of consumers were also reporting that their household was rationing their energy use, which had remained consistent with the previous wave (autumn 2022). This was a 16% increase in consumers reporting they were rationing energy due to financial concerns since

the spring 2022 wave.

The estimated age of home heating systems in Scotland varies considerably

Trends in boiler efficiency are closely related to developments in energy efficiency and building standards regulations, with 94% of domestic gas and oil boilers in Scotland having been installed since 1998, as a result of the European Boiler Efficiency Directive minimum standards coming into effect. In addition, the proportion of new boilers installed in Scotland has increased by 24 percentage points since 2010. The Scottish House Condition Survey also estimates that in 2019 around 87% of households in Scotland were using a gas or oil-fuelled boiler and over three-quarters (76%) of gas and oil boilers in Scotland were condensing

boilers. This represented an increase of four percentage points since 2018 and 54 percentage points since 2010 (Scottish Government, 2020b).

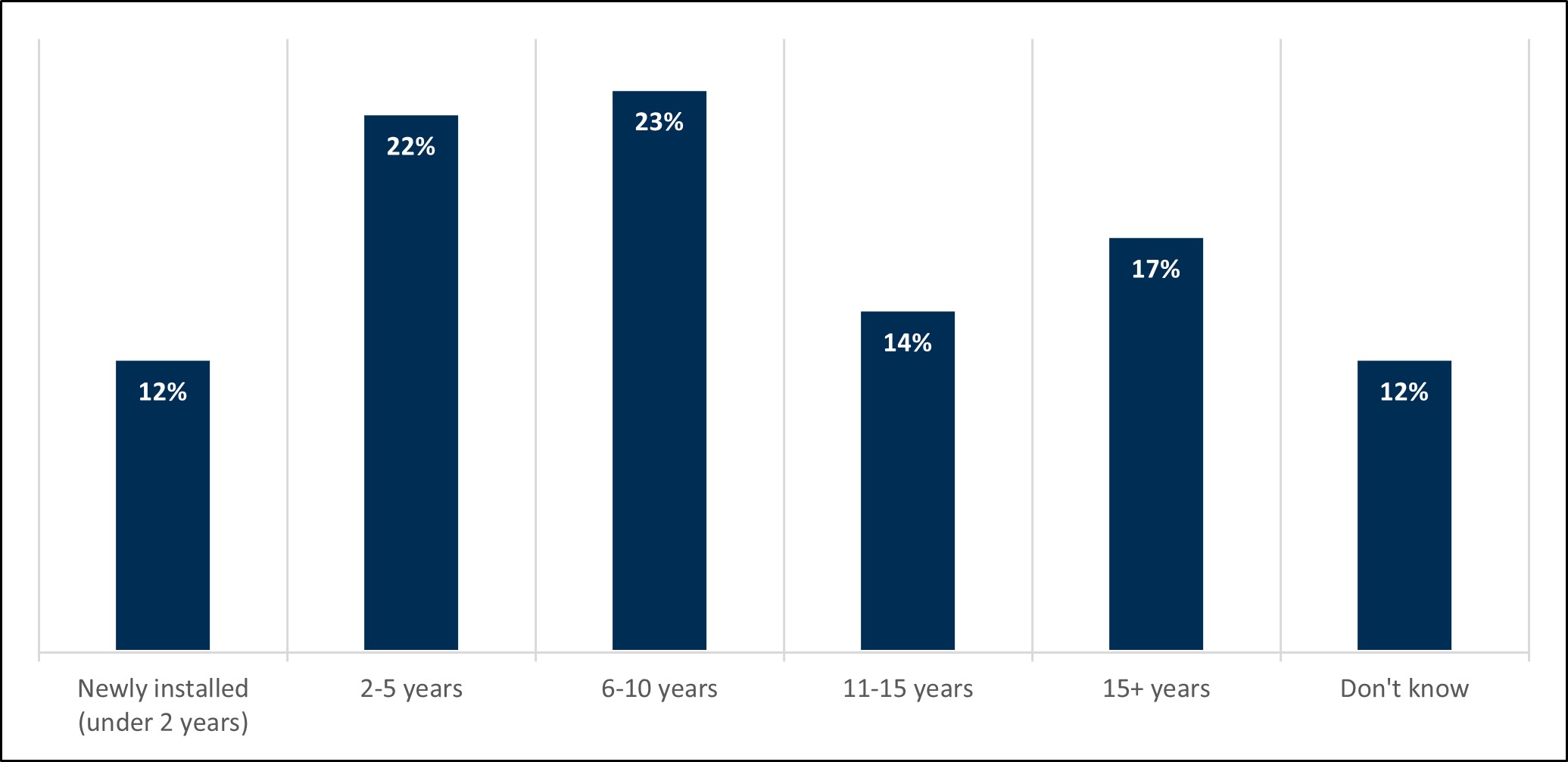

In our survey respondents were asked to estimate how old they thought their home heating system is. The results are summarised in Figure 5.

Figure 5 – The estimated age of home heating systems in Scotland varies

Age of home heating systems in Scotland estimated by respondents in answer to the question: "To the best of

your knowledge, how old is your home heating system?”

Weighted base: 2,264

The results in Figure 5 show that 57% of heating systems in Scotland are estimated to be under ten years old, with just over one in ten (12%) having been newly installed (less than two years old). A significant proportion (31%) are estimated to be over ten years old which will likely therefore need replaced sooner as those products reach the end of their serviceable lifespan. These may be the consumers more easily engaged in a conversation about low and zero emissions heating systems, as repair and servicing older systems

becomes more difficult or expensive. A more challenging group of consumers to engage in the conversation around home heating systems will be the nearly half of respondents (45%) in our survey estimating that their heating system is between two and ten years old, as

these are relatively recently installed systems that could work well for several years if they are serviced, and the costs of fuel remain affordable.

There was some variation in the estimated age of home heating systems by housing tenure. Those who own their home with a mortgage or loan are most likely to estimate that they have a newly installed system (16%), compared to those who own outright (11%), social

renters (10%), shared ownership (8%), and 3% of those renting from a private landlord. Though this variation may also be concealed by the higher rates of private renters (47%), social renters (19%) and those in shared ownership (17%) not knowing how old their home heating system is compared to those that own outright (7%) or buying with a mortgage or loan (7%). Caution is therefore advised when interpreting this data.

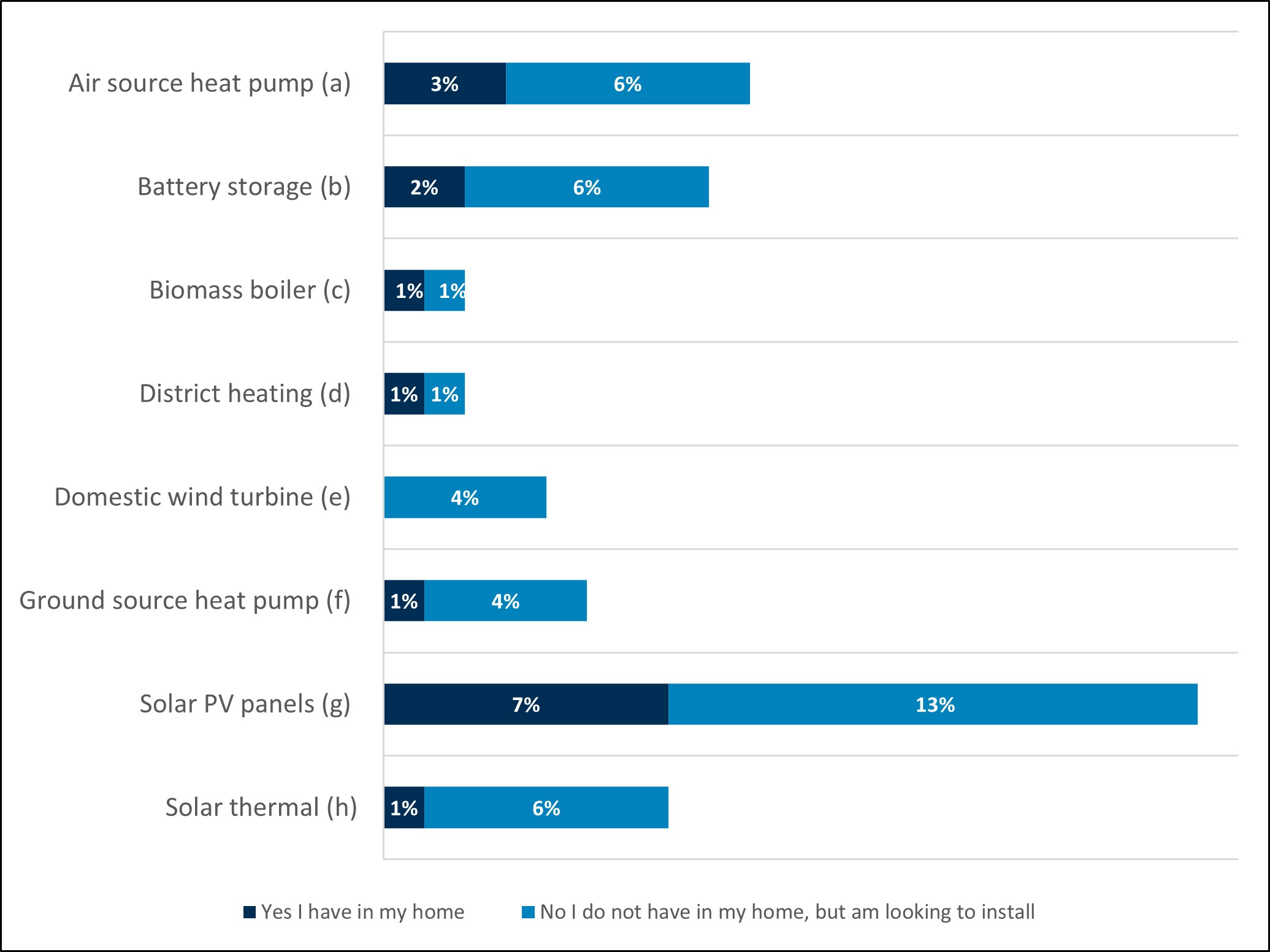

Consumer interest in renewable technologies is low, but will likely grow in the future

In our research we asked respondents whether they currently have or are looking to install in the future different renewable technologies at home. The results are summarised in Figure 6 and show that while a start has been made in Scotland, there is a considerable way

to go. A minority of respondents stated in our survey they have an air source heat pump (ASHP) (3%) or ground source heat pump (GSHP) (1%). It should be noted, however, that our survey results may be overestimating the prevalence of heat pumps in Scotland.

In an update by the Scottish Government (2021d) on progress made toward meeting the target of 11% of non-electrical heat demand from renewable sources by 2020, it was estimated that by the end of 2020 heat pumps saw the largest increase in number of installations and output in Scotland with an additional 3,020 installations contributing to an additional 83 GWh of output, compared with 2019. This brings the total heat output from heat pumps in Scotland to 390 GWh and the total number of installations to around 21,000.

The year on year increase of useful renewable heat produced by heat pumps was split between large heat pumps and new small units typically installed in domestic settings for the provision of heating and hot water. With annual rates of installation continuing around the 3,000 mark (Bowes, 2021), we might reasonably expect to be around 30,000 currently –

so about 1% of all households in Scotland, allowing for the above covering commercial and industrial too.

While caution is therefore advised regarding our survey results on the self-reported prevalence of heat pumps in Scotland, the Energy Saving Trust’s (2022) data on 2020-2021 Home Energy Scotland Loans shows that demand for funding to support the installation of

heat pumps in increasing. Funding committed through the Home Energy Scotland Loan scheme increasing by almost a third, from 586 systems in 2019-2020 to 762 systems in 2020-2021.

Figure 6 – Take up of renewable technologies in Scotland is low currently, but there is some consumer interest in these being installed in the future.

Responses to the statement: “For each of these please tell us if you have them in place or are looking to install” capturing whether renewable technologies are installed at the respondents’ homes, or they are looking to have them installed in the future.

Weighted bases:

(a) 2,207; (b) 2,241; (c) 2,249; (d) 2,248; (e) 2,234; (f) 2,203; (g) 2,251; (h) 2,242

Our results also show that around one in five state that they are looking to install either of these technologies in the future: 6% are looking to install an ASHP and 4% are looking to install a GSHP. Around three quarters (76%) stated they do not have an ASHP and they are

not looking to install them and a similar proportion (78%) stated they do not have GSHP and they are not looking to install them. Around 16% of respondents stated they do not know if they have an ASHP and 17% of respondents stated they did not know if they have a GSHP.

The other renewable technologies currently installed at home or technologies the respondents to our survey are looking to install in the future are also summarised in Figure 6. The results show that 7% of consumers in Scotland currently have solar photovoltaic (PV) panels, with a further 13% stating they do not have these currently, but they are looking to install the technology in the future. It is estimated that there are more than 144,000 homes with solar panels in Scotland, according to the Microgeneration Certification Scheme (cited by Jackman, 2023), which is roughly 6% of homes, indicating our survey results are broadly in keeping with official estimates.

There were only very low levels of respondents stating they currently have battery storage at home (2%), with a further 6% stating they do not have these but are looking to install them in the future. Similarly, only 1% of our respondents stated they currently have solar

thermal for heating water, while a further 6% don’t have these but are looking to install in the future. A further 1% currently use district heating and biomass boilers, with a further 1% interested in installing/connecting to these in the future. There was no one included in our

survey with a domestic wind turbine, though 4% of respondents were interested in having these installed in the future.

The renewable technology with most variation by age was related to solar PV panels and solar thermal technology. Those aged 16-34 (17%) and 35-44 (19%) were significantly more likely to say that they were looking to install solar PV panels than those aged 55-64 (9%) and 65+ (6%). Similarly, those aged 16-34 (9%) and 35-44 (6%) were significantly more likely to

say that they were looking to install solar thermal than those aged 65+ (3%).

Our findings on attitudes towards renewable technologies are significant in showing that while there appears to be some consumer interest in newer technologies that can help reduce the emissions from homes, there is some way to go in terms of building widespread consumer interest and support. This may indicate a lack of consumer awareness or knowledge around less familiar types of technology. This is related to the point made earlier that while consumers in Scotland are concerned about climate change, they may lack knowledge on what they can do about it.

This lends support to the Scottish Government speeding up its proposals for public engagement exercises for climate change and heat in buildings. This will go some way to equipping consumers with the knowledge they will need to feel adequately informed and from that behaviours will be able to change. This will, however, need to be backed up with adequate guidance and support, including financial support for the most vulnerable consumers to ensure that everyone benefits from the transition on an equitable basis.

The Scottish Government’s Heat in Buildings Strategy (HiBS) makes clear that to achieve Scotland’s net zero ambitions the country will need to rapidly scale up deployment of zero emissions heating systems so that by 2030 over one million homes and the equivalent of

50,000 non-domestic buildings are converted to zero emissions heat (Scottish Government, 2021a). In an online blog for ClimateXChange it was estimated that currently Scotland installs 3,000 low carbon domestic heating systems a year across all technology types and

between 517,000 and 717,000 domestic properties will be required to install heat pumps in Scotland by 2030 to meet climate targets (Bowes, 2021). However, for the heat transition to be a success, all of this will need to be done in a way that will protect those in or at risk of

fuel poverty from increased energy costs and avoid placing a burden on those least able to pay.

Consumers perceive renewable technologies as better for the environment, but more costly to install and run

To be able to promote the uptake of renewable technology alternatives at the scale required to meet the Scottish Government’s ambitions as laid out in the HiBS will require widespread and improved awareness of renewable technology options available to consumers.

The homebuilding, extending and renovation sector estimates the cost for an air source heat pump installation on a new build property would be between £8,000 to £16,000 and potentially as much as £28,000 on an existing property (Hilton, 2021). This estimated cost is at the top end of estimates and would include upgrading radiators and replacing pipework.

The homebuilding, extending and renovation sector also estimates the cost of installing a ground source heat pump would be around £14,000 to £25,000 or possibly more if a large borehole collector is required. Though other estimates of the capital costs of adopting heat

pumps have suggested replacing gas and oil-heated homes heating systems will cost between £11,290 and £14,300 (Palmer and Terry, 2023). In the same analysis, electrically-heated homes replacement heating systems is estimated to cost somewhere in the range £10,480 to £19,980. This compares to the average cost for purchasing and installing a standard combi boiler being between £2,000 to £3,000 for a simple gas boiler replacement.

In our survey, two thirds (66%) of all respondents net agreed that renewable energy technologies are more expensive to install when compared to gas-based alternatives. Interestingly, 80% of respondents on the highest incomes (> £100,000) believe renewable

energy technologies are more expensive to install when compared to gas-based alternatives, versus 59% of respondents on the lowest incomes (< £15,000) stating the same. Speculatively it could be that people with most money have looked into the cost of renewable technology, so therefore have a more realistic understanding of the costs involved.

Over a quarter (27%) of all respondents stated a belief that renewable energy technologies are cheaper to run when compared to gas-based alternatives. There was no statistically significant difference in the responses by income group, though respondents on higher incomes were marginally more likely than those on lowest incomes to state a belief that they are cheaper to run (29% of those on incomes > £100,000 compared to 25% of those on incomes < £15,000).

Our survey results also indicate a significant majority of all respondents (62%) agreed that renewable technologies are better at reducing carbon emissions, with only a minority agreeing that renewable energy technologies are more reliable to use (19%) and that they are better at heating homes than gas (16%).

These results should be caveated by the fact they are gathering consumers immediate responses to the question asked. There is no way of knowing from the data collected how aware or experienced the respondents were of renewable technologies. It should also be noted that there were high occurrences of “don’t know” responses to the question. This may reflect an unfamiliarity with renewable technologies in the general population or a lack of accurate knowledge from which to form an opinion. But if the results are taken at face

value, it is clear that there was a dominant view amongst respondents that renewable energy technologies are more costly to run in comparison to gas alternatives.

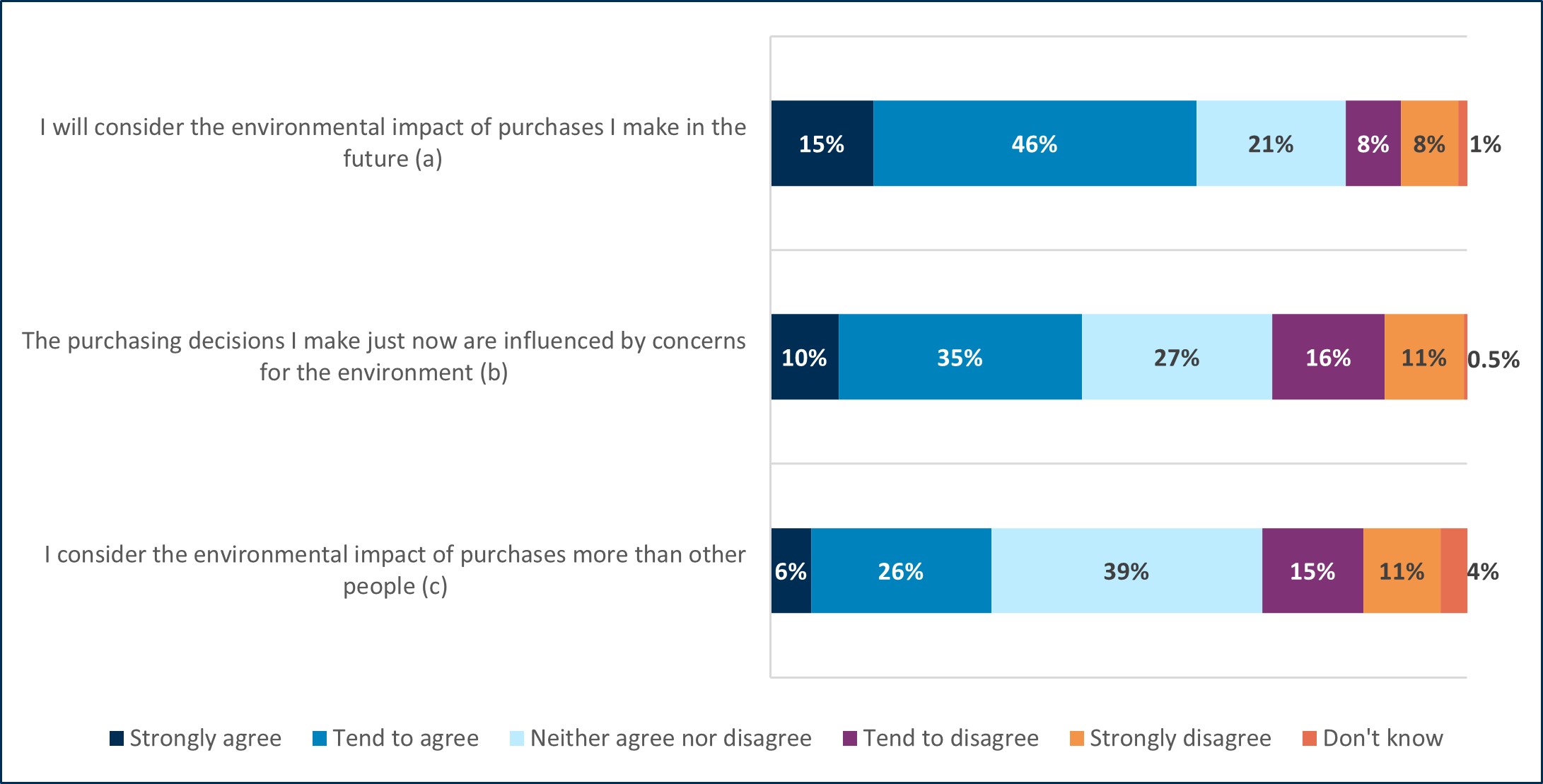

Consumers recognise the impact of specific energy related behaviours, but convenience and cost matters

Our survey asked respondents to rank the impact on the environment they believe would stem from undertaking a range of specific energy related behaviours:

- Improving energy performance

- Saving energy through low cost measures

- Installing a new home heating system

- Installing renewable energy technology

- Switching to hybrid or electric vehicles

- Installing heat pumps

The respondents generally viewed the full list of different types of measures as having at least some impact on the environment, but to varying degrees. Saving energy at home by improving the home’s energy performance (e.g. better insulation, replacing doors/windows,

installing underfloor heating, etc.) was considered to be the most impactful intervention, closely followed by saving energy at home (e.g. switching off lights, turning down a heating thermostat, etc.), and installing new home heating systems that produce fewer greenhouse

gas emissions (e.g. more efficient electric heating). The intervention viewed as having least impact on the environment was installing heat pumps, closely followed by switching to a hybrid or electric vehicle when you replace your current vehicle.

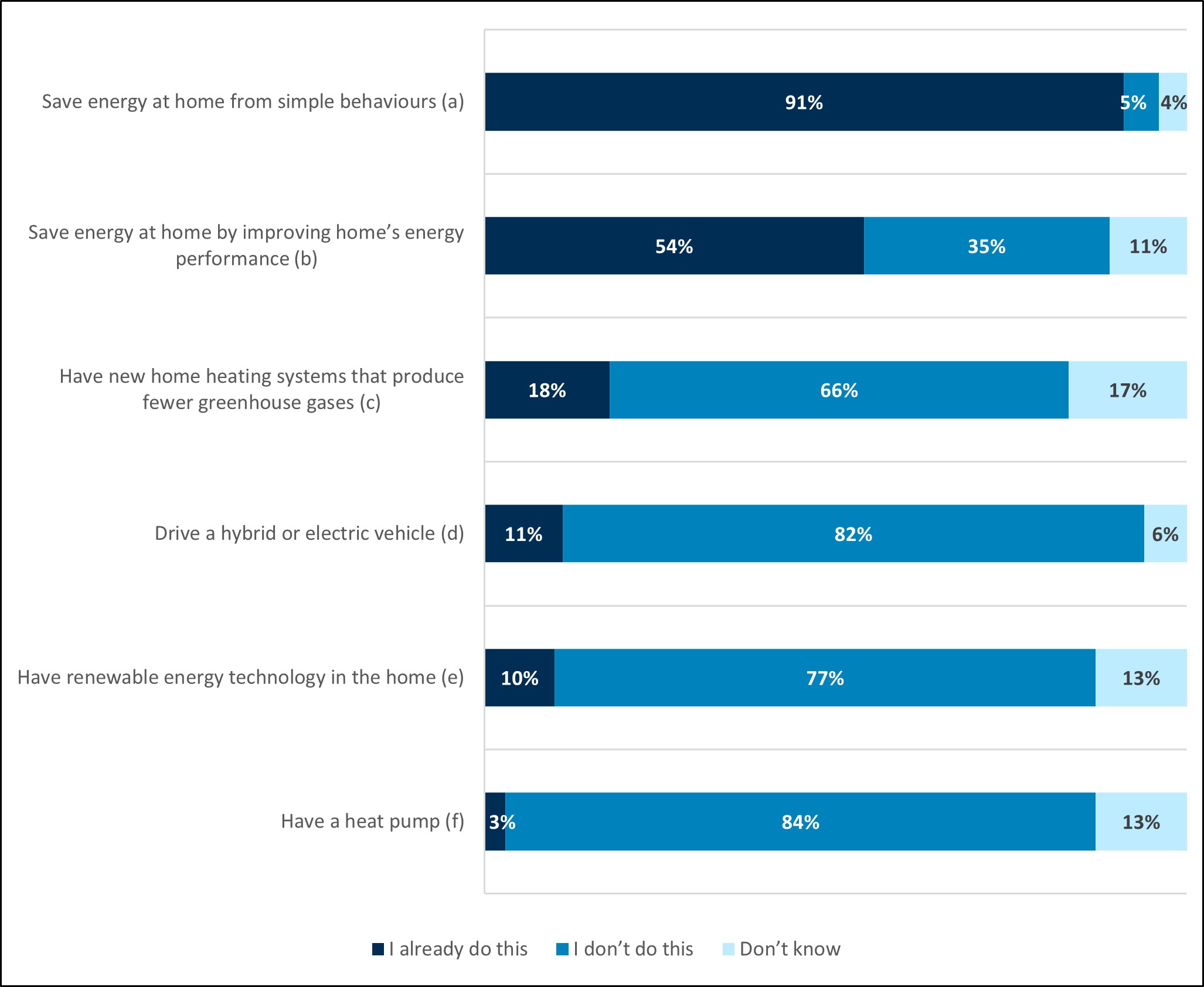

Our survey asked the respondents to indicate which of the energy related behaviours listed above they personally do/have done and those they personally do not do/have not done. The results are summarised in Figure 7 and show that the majority of respondents (91%) self-reported that they are already saving energy at home through low cost measures (such as switching off lights and turning down a heating thermostat). In addition, more than half (54%) of respondents reported they have saved energy at home by improving their

property’s energy performance, for example through better insulation, replacing doors/windows, or installing underfloor heating.

However, over a third (35%) of respondents stated they have not sought to save energy at home by improving their property’s energy performance already and most respondents reported they do not have a heat pump (84%), drive a hybrid or electric vehicle (82%), nor

have renewable energy technology in their home (77%). The apparent consumer reluctance around switching to electric or hybrid vehicles is particularly interesting, given that according to Transport Scotland (2022), new registrations of electric or hybrid-electric vehicles have seen steady increases in new registrations in recent years, to currently be sitting at around 18,437, or 10% of new registrations.

In addition, of the 10% of respondents in the survey stating they had installed/have some sort of renewable energy at home, the single biggest motivating factor was lowering energy costs (63%), followed by increasing the energy efficiency of the home (39%), and a third

(33%) stated a belief that it is their personal responsibility to help tackle climate change.

Figure 7 – The majority of respondents self-report they are already saving energy at home through low cost measures and more than half report they have saved energy at home by improving their property’s energy performance.

Responses to the statement: “Looking at the list below, some people already do some of these things while

others do not. Please indicate which you already do and which you do not do currently”.

Weighted bases:

(a) 2,242; (b) 2,239; (c) 2,242, (d) 2,241; (e) 2,243; (f) 2,243

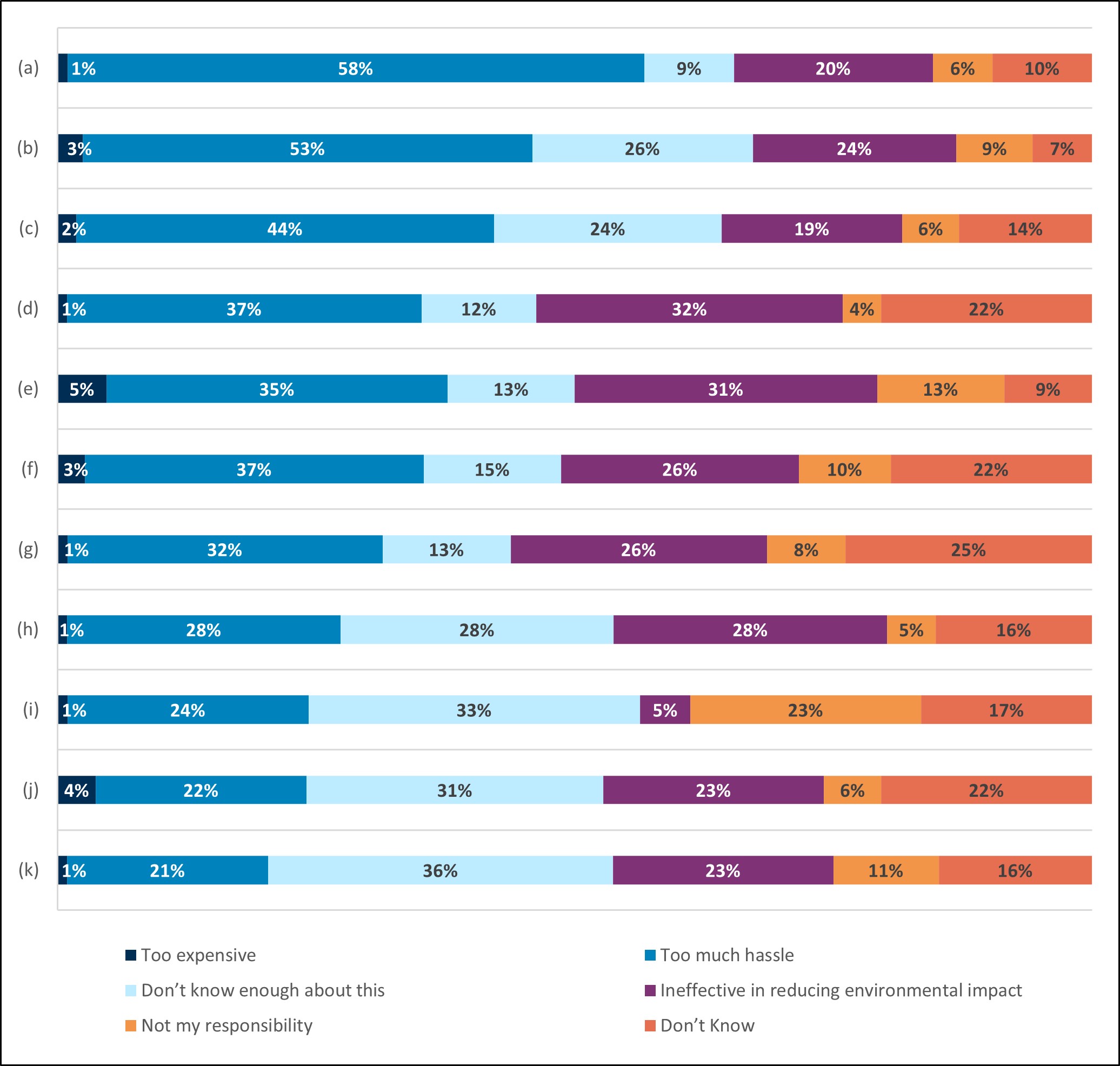

Cost remains a significant barrier to some energy interventions

In terms of the barriers consumers face for installing or having energy interventions at home our research suggests that a lack of information is important. As shown in Figure 8, cost was identified as the biggest barrier to driving a hybrid or electric vehicle (76%), having a new home heating systems installed that produce fewer greenhouse gases (68%), having a

renewable technology in their home (66%), saving energy by improving the home’s energy performance (62%), and having a heat pump installed at home (59%).

Figure 8 – The most commonly self-reported barrier for installing energy interventions is cost, especially for measures perceived by respondents to be higher cost interventions.

Responses to the question: “If selected ‘I don’t do this’ (in Figure 7), why do you not?” Select all that apply.

Weighted bases:

(a) 108; (b) 711; (c) 1,382; (d) 1,589; (e) 1,630; (f) 1,732

Just under a quarter (23%) of respondents stated that they do not know enough about heat pumps to be able to form a view, indicating a potential lack of appropriate knowledge around that particular measure. However, making comparisons about installation and running costs between familiar carbon intensive technologies and less familiar renewable technologies, such as heat pumps, can be difficult because these can depend on the size and type of property, how much insulation it has, the type and age of radiators, the efficiency of the boiler, the price of gas relative to electricity over time, and grants available for installation. Nevertheless, if there is a perception amongst the public that heat pumps are

more costly to install and run than gas boilers, then it is reasonable to assume that more work will be required to help consumers understand the true extent of installation and running costs.

For the minority of respondents not currently saving energy at home by undertaking low cost interventions (such as switching off lights or turning down a thermostat), the main view expressed here was related to this type of intervention being too much hassle to do

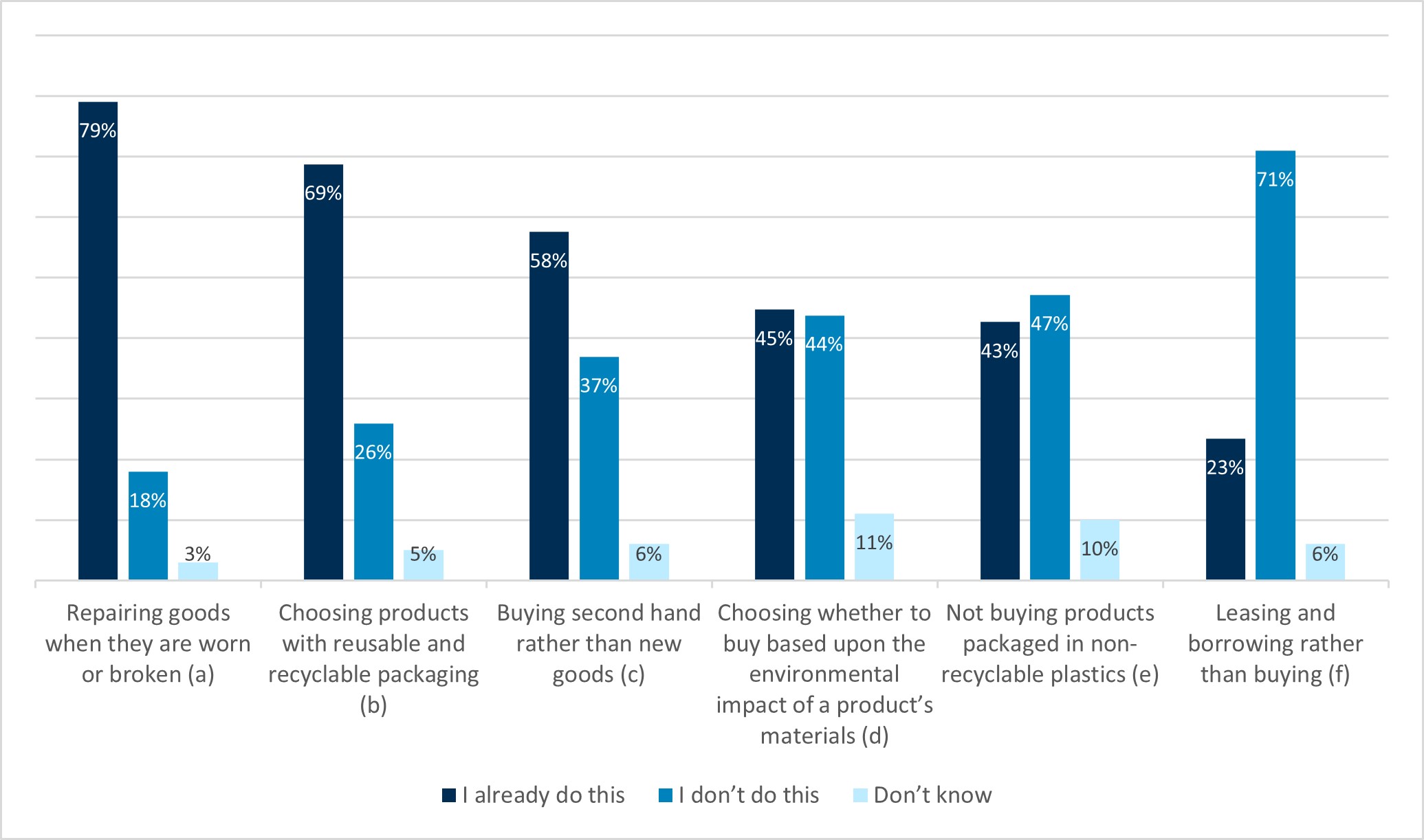

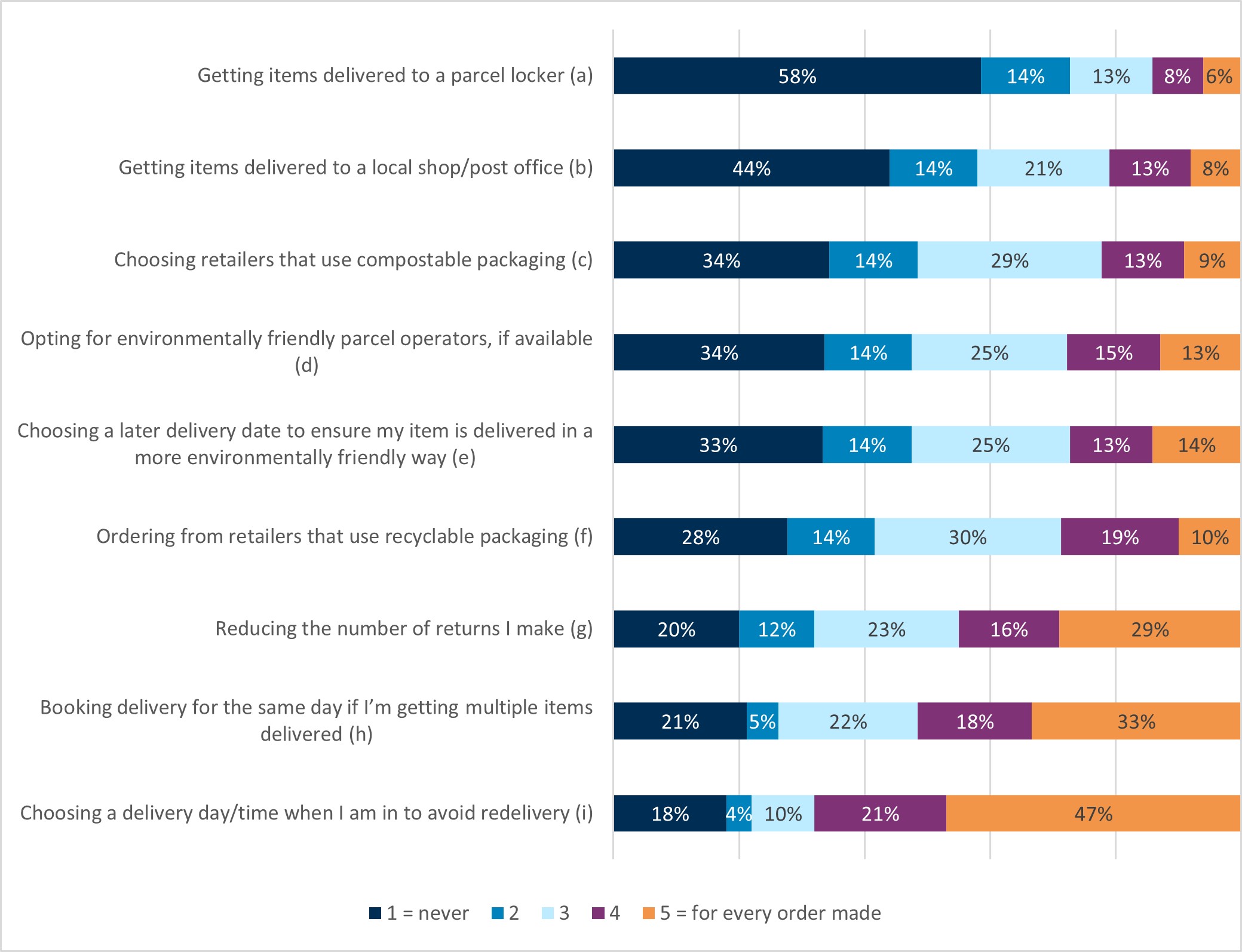

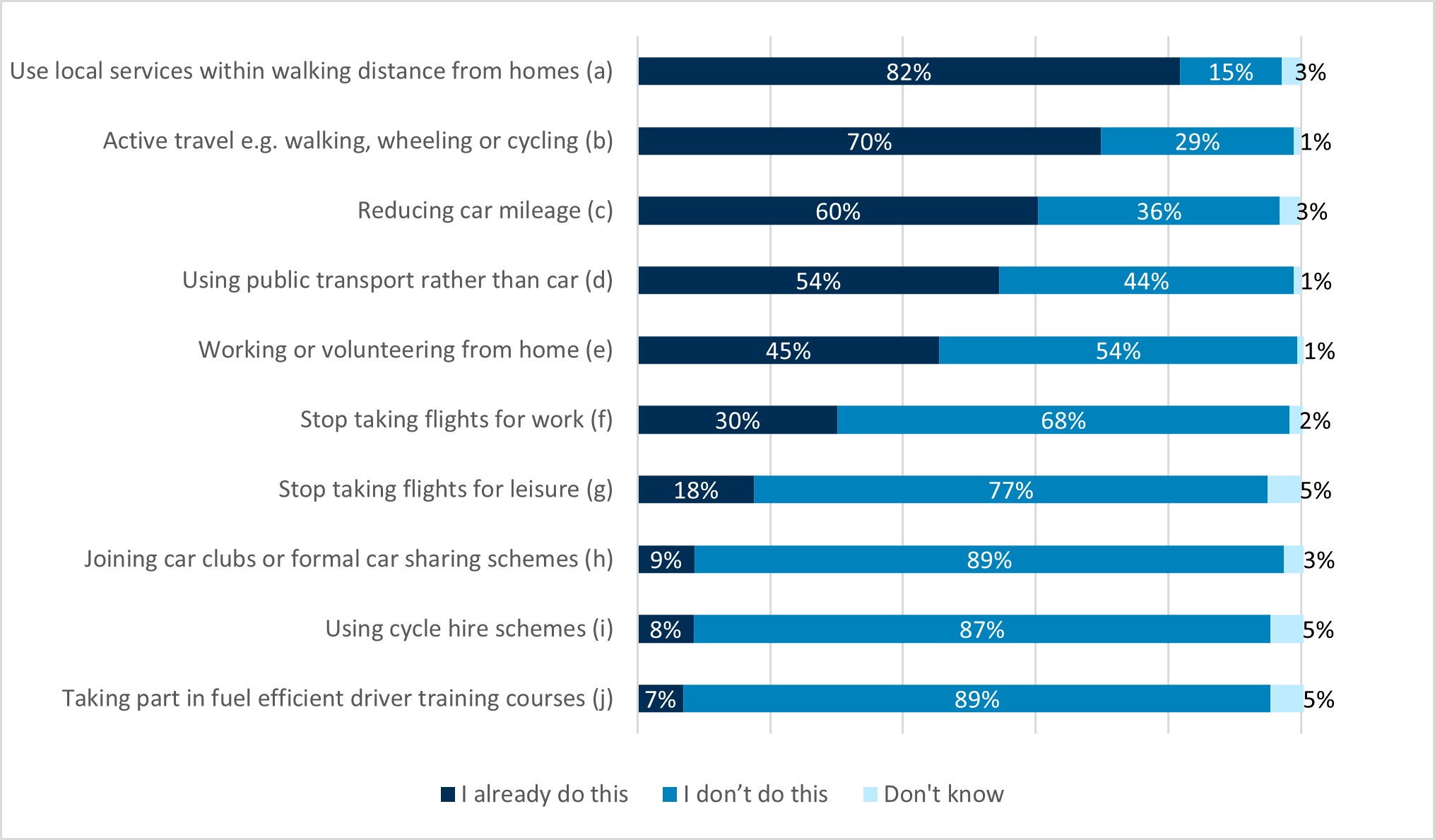

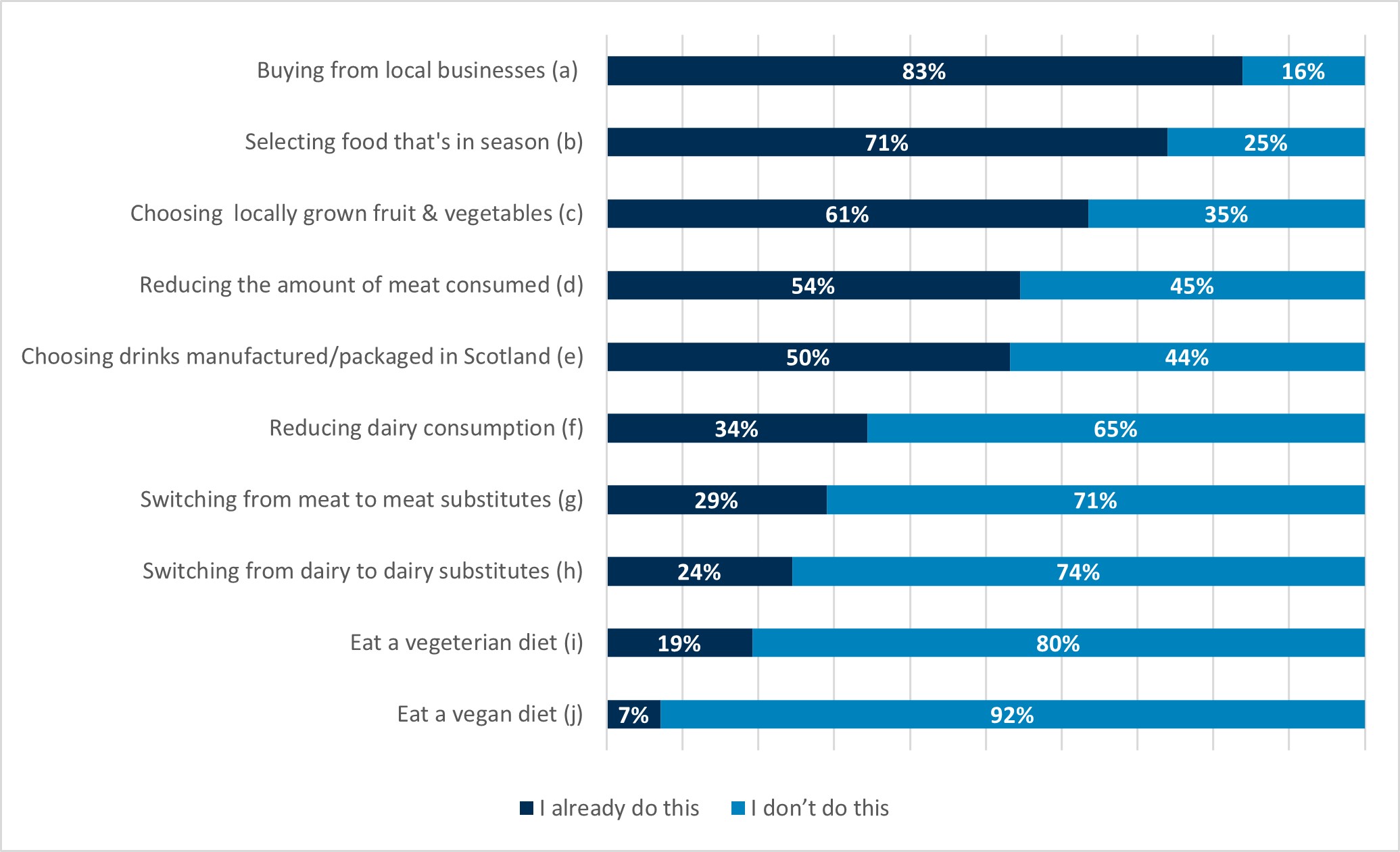

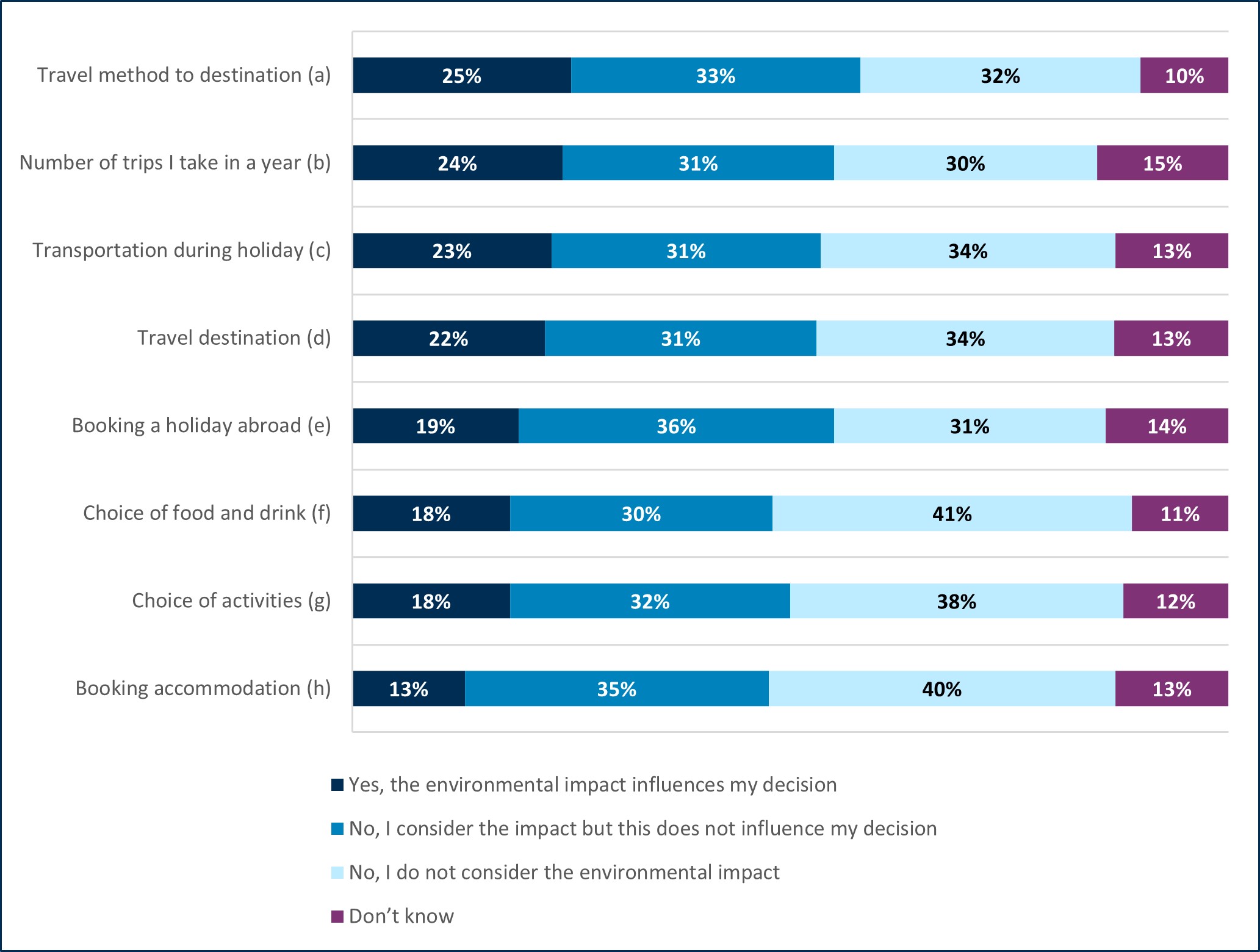

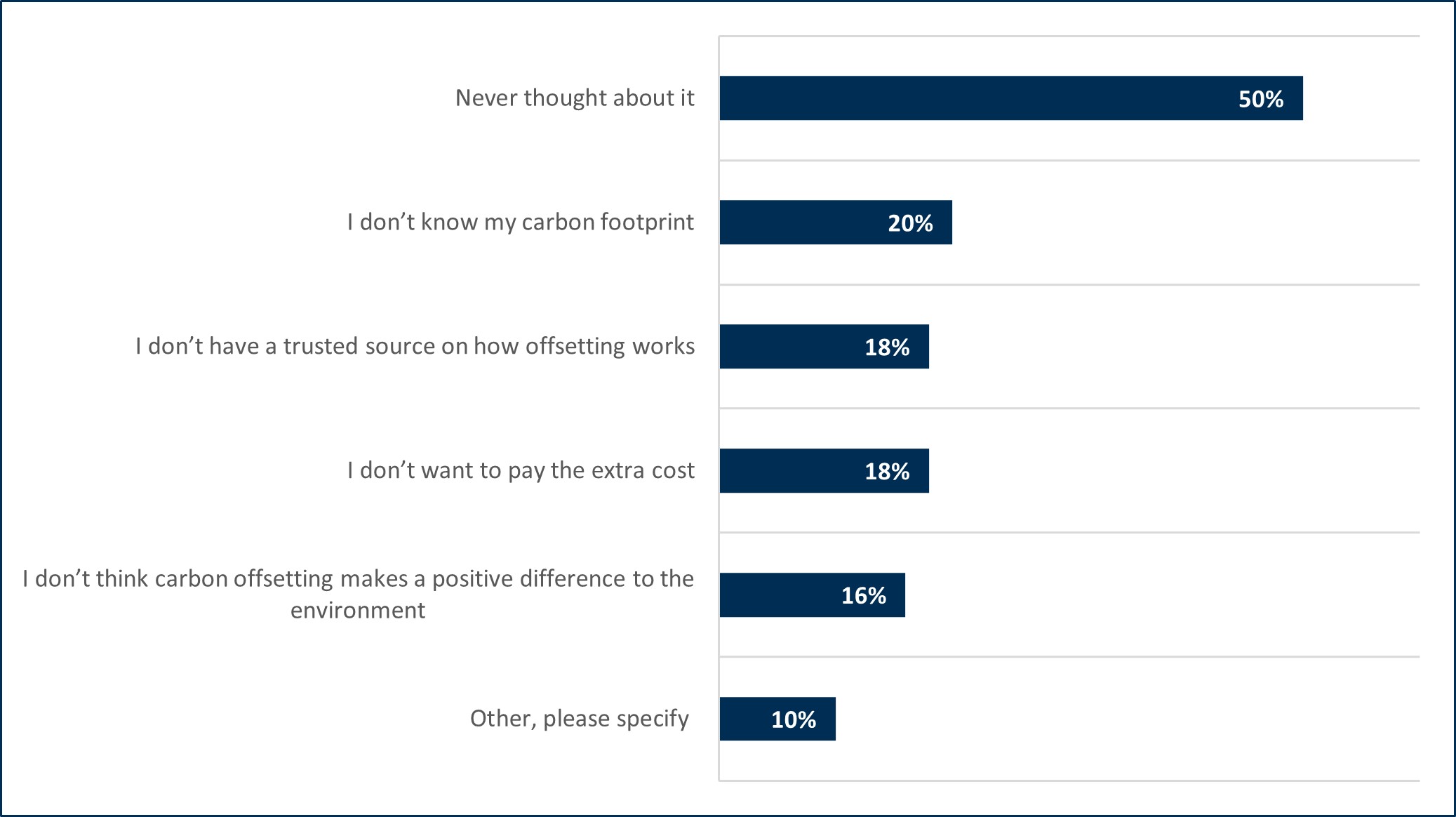

consistently (34%), or the intervention is perceived as being ineffective in reducing the environmental impact (33%).