1. Executive Summary

Improving outcomes for disabled consumers in rural Scotland

Disabled consumers and consumers in rural areas in Scotland can each face a range of challenges in accessing different markets and services. However, there is relatively limited existing evidence on the experiences of consumers who are both disabled and who live rurally.

This has consequences for policy, regulatory, and legislative responses in Scotland, which may require to be strengthened to better address the compound impact that consumers encountering multiple inequalities can experience.

To address the evidence gap and identify key areas for action Consumer Scotland:

Reviewed the existing evidence base in relation to rurality and disability in Scotland, focusing on current issues around affordability, choice and accessibility

Commissioned new qualitative research, working with independent research agency Thinks Insight and Strategy (Thinks), to examine how living in rural communities in Scotland can impact disabled consumers’ experiences in terms of their ability to access consumer goods and services and participate in everyday activities. The qualitative research focused specifically on disabled consumers experience with transport, health and social care, and leisure activities. These were identified with participants during scoping interviews as areas which had the greatest impact on their lives, or that were considered under-researched.

Undertook internal quantitative analysis using data from the Scottish Household survey to identify how, if at all, the intersection of rurality and disability impacts the experiences of consumers in relation to transport, health services and participation in leisure activities, when controlling for other inequality categories such as age, gender or socioeconomic status.

Key Findings

We reviewed the existing evidence base in relation to rurality and disability in Scotland, focusing on current issues around affordability, choice and accessibility. Our analysis of the Scottish Household Survey 2022 found that:

- 26% of adults in Scotland have a disability defined in this analysis as a physical or mental health condition or illness lasting longer than 12 months

- 19% of adults in Scotland live in a rural location – defined using the two-fold urban rural Classification (2020)

- 5% of adults in Scotland live in a rural location and have a disability

Our broader review of the existing evidence found that:

- Disabled people are more likely to have lower incomes and face additional costs

- Consumers living in rural areas face a rural premium, with significant additional costs in relation to transport and energy. These additional costs vary depending on the type of goods and services, household composition and whether it is a remote rural or an island location

- Being able to access transport is essential for rural and disabled consumers. However, fewer public transport options in rural areas results in a greater reliance on car use. Disabled consumers also face a range of accessibility challenges in relation to public transport

- Health and social care services may not always be easily available in rural areas

To better understand the experiences of disabled rural consumers we commissioned new qualitative research, speaking directly with consumers to:

- Identify the key issues experienced by disabled consumers living in rural Scotland and how this impacts on their ability to participate effectively in everyday activities and consumer markets

- Understand the key priority issues for disabled people living in rural Scotland in relation to improving their ability to participate in everyday activities and consumer markets

- Provide opportunities for disabled consumers to contribute to how these issues could be addressed by policy makers and organisations

There are many elements of rural life that the people engaged with for this research enjoy, including the local scenery, relative quiet, and some experiences with specific services. The research did, however, uncover a number of often inter-linked challenges faced by disabled consumers in rural areas.

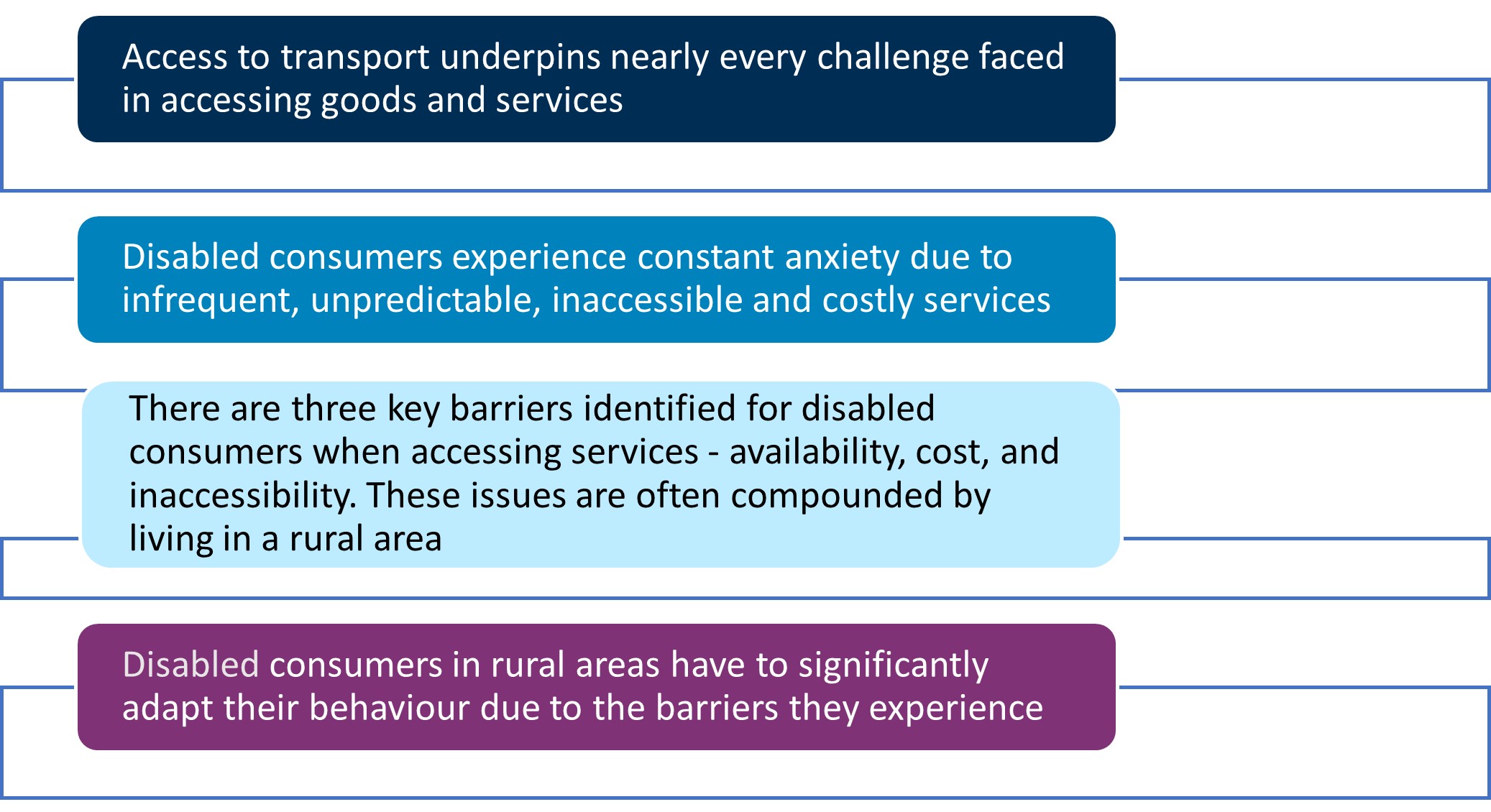

Four key themes stood out for the disabled consumers who participated in the qualitative research.

Access to Transport

The cost, availability, and accessibility of transport, both private and public, is seen as a significant issue for rural consumers generally, with the effects of these barriers being more acute for disabled people given their greater likelihood of living in poverty and having fewer accessible transport options. Issues around access to transport also have wider implications,

affecting consumers’ ability to access other services explored in this research.

Psychological impacts of barriers to accessing services

Dealing with issues relating to the unreliability, cost and inaccessibility of services can have a negative psychological impact on disabled consumers in rural areas. The anxiety and stress caused by this unpredictability and the fear of potential adverse consequences often put participants off using public transport or accessing health or leisure activities at all. As a result, disabled consumers living in rural areas face a significant planning burden, along

with constant worry about something going wrong during journeys to access key services.

The three key barriers of availability, cost and inaccessibility

Three key barriers to accessing transport, health and social care and leisure activities were commonly identified by participants in the research. These are: a lack of available services, cost and inaccessibility. The separate and cumulative effects of these barriers mean that disabled participants can experience significant challenges when seeking to use transport, health and social care and leisure activities.

The availability of transport, health and social care and leisure activities can differ, sometimes significantly, between the different areas in rural Scotland they lived in, creating a ‘postcode lottery’.

Health and social care services are often difficult to access, requiring long and challenging journeys, incurring significant wait times or being unavailable at times that work for consumers. Many disabled participants also described difficulties coordinating appointments, with long wait times exacerbating the symptoms of their disabilities. The cost of travel, and in some cases accommodation, can also be prohibitive as even if costs can be reimbursed, this may need to be paid upfront. Overall, these difficulties can result in consumers missing important appointments or treatments.

Leisure options are also regarded as being limited, with few local activities suited to disabled people. Some leisure activities were only available certain times of the day or year. Research participants reported that of the limited leisure options available to them, even fewer were available on affordable terms. Significant upfront costs or inflexible booking systems can also make costs harder to accommodate, and leisure opportunities were among the first things sacrificed when budgets were tight.

Services often had either direct or associated costs for participants, and given that disabled consumers are more likely to be on low incomes, the relative impact of this can be greater. Transport - whether public or private -was often expensive, especially when booked near to the time of travel.

While the experience of disabled people in relation to inaccessibility varies depending on the nature of their condition, a number of different challenges were highlighted. In relation to transport, these included being unable to physically access public transport, issues around parking for blue badge holders and the inability to easily undertake door-to-door travel. Other issues such as the inability to access toilets during journeys or to be able to travel with carers or companions are also significant barriers to accessing public transport.

Disabled consumers in rural areas have to significantly adapt their behaviour due to the barriers they experience

Disabled consumers living in rural areas face a significant planning burden and must plan ahead and sometimes significantly adapt behaviour to reflect the barriers they face accessing services. At times this means they incur additional costs, compromise on the care they receive, avoid certain situations or reduce or self-exclude from activities. Disabled participants, consequently, had more limited choices in which goods and services they could access, and how. In some cases, they had no choice at all, leading to social isolation.

Quantitative analysis of the impact of being disabled and living in a rural area

Overall, our statistical analysis of the Scottish Household Survey found that that in some instances (outlined below) the experience of disabled people is impacted due to the fact they live in a rural area and for others they are impacted as a result of being disabled. For example:

- There is a significant difference in the frequency of public transport use between people living in rural and urban areas, with rural residents more likely to report using them less frequently. However, disability status does not have a significant impact on the frequency of bus and train use and there is no difference in the frequency of bus and train use of disabled adults based on whether they live in rural or urban areas.

- Disabled people and those in rural areas are less likely to have participated in cultural activities in the last 12 months than people living in urban areas who are not disabled. However, there is no additional combined effect on cultural participation of being both disabled and living in a rural area.

- In relation to health services our analysis found that people living in urban areas are less satisfied with their local health services while disability status does not significantly affect satisfaction levels.

We did not find that rural disabled people experience a statistically significant compounding impact on their experiences from being both disabled and living in a rural area.

The experiences reported by our qualitative research participants and stakeholders suggest, however that there may be a more complicated reality that is harder to capture with quantitative data alone. We note that that the lived experience of rural disabled participants reported in the qualitative research are no less real simply because there is no statistically significant evidence of intersectionality.

Areas for improvement and recommendations

To address the challenges facing disabled rural consumers across key services, Consumer Scotland has identified a number of areas in which action can be taken to improve outcomes for consumers. These include actions to:

- Improve the financial position of disabled consumers in rural areas

- Prioritise the use of inclusive design to improve service design and delivery

- Build capacity and resilience in local services

- Focus on the role of transport in enabling access to other services

- Develop and share best practice in relation to the delivery of health and social care services

- Tackle barriers to leisure access and

- Address gaps in the evidence base

Recommendations

Strategic Recommendations

1. Key sector bodies, including Regional Transport Partnerships, Health and Social Care Partnerships and Culture and Leisure trusts should review and seek opportunities to strengthen the voice and representation of disabled rural consumers in their decision-making processes. This may include, for example, consideration of consumer panels and/or other formal mechanisms to enable consumer involvement in organisational structures. There should be a focus on ensuring that particular consideration is given to the involvement of those with lived experience within any such consumer-representation arrangements.

2. The Scottish Government should undertake a short strategic review of the range of key strategies it currently deploys that have a central role in tackling the challenges experienced by disabled consumers in rural areas across a range of sectors, to ensure policy coherence and ensure a clear, joined-up focus on the delivery of tangible changes that will improve outcomes for the consumers across the policy areas they cover. Relevant plans include the Scottish Government’s 2025 Disability Equality Plan[1], the National Islands Plan[2] along with the forthcoming Rural Delivery Plan[3] and Just Transition Plan for Transport.

The short strategic review should identify:

- the key linkages between the relevant plans

- areas which are complementary

- gaps, including gaps in the assessment of impacts of policies on rural or disabled consumers and any duplication in activity

- any differences in approach or priorities

3. Following completion of the review, the Scottish Government should set out specific actions that it and other stakeholders will take to ensure that the various strategies provide a coherent framework for improving outcomes for disabled rural consumers, maximising the opportunities for improvement and mitigating the risks of harm.

4. As a specific part of its review, the Scottish Government should explicitly consider the approach that each strategy takes to recognising and improving the financial position of disabled rural consumers. The Scottish Government should consider what scope exists to take further action on this issue under each of the relevant strategies, recognising the significant financial barriers that many disabled rural consumers face, as set out in this report.

5. As part of the implementation of its key strategy and delivery plans, including the Rural Delivery Plan, National Islands Plan and Disability Equality Plan, the Scottish Government should work to develop the evidence base on issues facing disabled rural consumers across key services building on the findings from Consumer Scotland’s report.

6. Following this evaluation of the Fairer Funding Pilot, which highlighted the potential benefits of multi-year funding for Third Sector organisations and the communities they serve, the Scottish Government should set out the implications and intended approach emerging from the pilot. This will help shape a broader future funding approach that builds greater resilience in local services, including those delivering for disabled consumers in rural areas.

7. All public bodies involved in the commissioning, procurement and delivery of services such as transport, health and social care and leisure activities in rural and remote areas should apply the Consumer Duty when taking strategic decisions, to assess whether these services are accessible and affordable for all consumers, including disabled and rural consumers.

Sector Specific Recommendations

Transport

8. Local authorities, local bus companies and ScotRail should carry out a strategic review of their accessibility policies and reporting procedures for consumers who experience accessibility issues on public transport. They should then build capacity to respond to reported issues, so that these are investigated and addressed. This would support more consumers to report accessibility issues they face at specific bus stops, rail stations, and ferry ports, and address ongoing accessibility barriers for consumers.

9. Local authorities, Regional Transport Partnerships, and the Traffic Commissioner should work together to identify rural areas where there are lower levels of PSVAR accessible buses in operation and to explore how they can support local operators with smaller vehicles to increase the proportion of their fleets that meet accessibility standards.

10. Regional Transport Partnerships and Transport Scotland should:

- Carry out further piloting and evaluation of Demand Responsive Transport and Mobility as a Service schemes, especially in rural areas, to determine how they can better serve consumers in these areas.

- Work in partnership with local authorities to identify rural areas where DRT may be strategically deployed, for the purposes of these pilots. This could help to gather insights on how to support and fund DRT schemes that can run in a financially sustainable way, and become better integrated with existing networks so that consumers, and especially disabled consumers, have greater awareness and confidence in accessing them.

Health and Social Care

11. The National Centre for Remote and Rural Health and Care (NCRRHC) should lead work to further establish and promote best practice relating to the design and delivery of health and social care to disabled consumers in rural areas. This may include the development of further guidance for health boards and providers to support them to improve the accessibility, affordability, and availability of healthcare to disabled people in rural areas.

12. A specific element of this work should focus on improving transport to health care settings. NCRRHC should work with Public Health Scotland to review the implementation of sections 120 and 121 of the Transport (Scotland) Act 2019, which requires health boards to work with community transport providers to help provide non-emergency patient transport services, with a specific focus on whether this legislation has been effective in resolving issues for disabled consumers in rural areas and facilitating improved partnership working between the community transport sector, NHS and the Scottish Ambulance Service

13. The Scottish Government and local authorities should work together in the delivery of the Disability Equality Plan to improve the information available to disabled people in rural areas about their right to self-directed support. This could help disabled people better tailor their health services to their needs. This may be achieved by co-producing information with disabled people’s organisations to be disseminated by these organisations as well as relevant community organisations in more remote and island areas.

Leisure Activities

14. We support the recommendation of the Accounts Commission that Local Authorities and COSLA should work to understand how individual services interact, in order to strengthen their understanding of the possible longer-term effects of the decisions they are taking now to address financial pressures. We agree with the Accounts Commission that consideration of the performance of these service, and decisions around funding, should be supported by a wider range of indicators of performance for culture and leisure activities, supported by clear, balanced and transparent local performance reporting and monitoring. These should not focus only on attendance or satisfaction, but also on how they contribute to wider impacts such as wellbeing and tackling loneliness. Finally, we agree with the Accounts Commission that improved consultation and equalities impact assessments could better inform local spending decisions related to leisure, especially when charges or changes to eligibility are being considered.

15. Local authorities should carry out a review of the Core Path networks in their area, to identify opportunities to improve accessibility and enable a greater number of disabled consumers to make use of these resources.

2. Acknowledgements

Consumer Scotland would like to thank the consumers who gave up their time to share their experiences of being a disabled consumer living in rural Scotland. Their first-hand accounts of their day-to-day experiences have provided unique insights to help us advocate for ways to improve and develop services. As Experts in their Experience they are uniquely placed to help improve, plan and develop those services. We are hugely appreciative of their willingness to share their insight with us.

We would also like to thank the disabled people organisations and stakeholders for their contributions, guidance and advice, including Enable Scotland, DG Voice and Kyleakin Connections who, amongst others, helped to facilitate this research. We are very grateful for your support and collaboration.

3. Who we are

Consumer Scotland is the statutory body for consumers in Scotland. Established by the Consumer Scotland Act 2020, we are accountable to the Scottish Parliament. The Act defines consumers as individuals and small businesses.

Our purpose is to improve outcomes for current and future consumers, and our strategic objectives are:

To enhance understanding and awareness of consumer issues by strengthening the evidence base

To serve the needs and aspirations of current and future consumers by inspiring and influencing the public, private and third sectors

To enable the active participation of consumers in a fairer economy by improving access to information and support

Consumer Scotland uses data, research and analysis to inform our work on the key issues facing consumers in Scotland. In conjunction with that evidence base we seek a consumer perspective through the application of the consumer principles of access, choice, safety, information, fairness, representation and redress.

We have a particular focus on three consumer challenges: affordability, climate change mitigation and adaptation, and consumers in vulnerable circumstances.

4. Introduction

Consumer Scotland has a statutory responsibility to have regard to the interests of consumers in vulnerable circumstances.

This is defined as consumers, who by reason of their circumstances or characteristics may have significantly fewer or less favourable options as consumers than a typical consumer, or are otherwise at a significantly greater risk of harm being caused to their interests as consumers, or harm caused to those interests being more substantial than would be the case for a typical consumer.[4]

The particular challenges experienced by disabled consumers and rural consumers in Scotland have been considered by a range of reports and research studies, including Consumer Scotland’s comprehensive 2023 literature review on consumer vulnerability.[5] A wide range of policy and regulatory interventions have been enacted over several years to attempt to respond to specific challenges facing disabled consumers and rural consumers in different consumer markets and sectors. There have also been a number of cross-cutting policy responses such as the Scottish Government’s 2025 Disability Equality Plan[6], its National Islands Plan[7] and its forthcoming Rural Delivery Plan.[8]

The 2023 Consumer Scotland literature review on consumer vulnerability highlighted the limited existing research base examining the experiences of individuals who have more than one characteristic that may increase the risk of consumer vulnerability, in a Scottish context.[9] Existing research tends to examine disability and rurality individually in isolation and does not examine the cumulative and combined impact of being both disabled and living in rural areas in Scotland.

This has consequences for policy, regulatory and legislative responses in Scotland. These interventions may require to be strengthened to better address the compound impact that consumers encountering multiple inequalities can experience.

To help address this issue, Consumer Scotland commissioned qualitative research, undertook analysis of relevant Scottish Household Survey data and engaged with stakeholders to establish an improved evidence base on the specific experiences of consumers in Scotland who are both disabled and living in a rural area.

Our scoping review highlighted a number of markets as presenting a range of challenges both for disabled consumers and for consumers living in rural areas. Our research partner, Thinks Insight and Strategy, worked closely with a small group of stakeholders and disabled consumers living in rural areas to identify three particular markets which are priority areas for them. These are:

- Transport

- Health and Social Care and

- Leisure Activities

This report sets out the key findings from the research and analysis and makes a number of recommendations for interventions that can contribute to improving outcomes for disabled consumers in rural Scotland.

In reaching our conclusions we note that that what is right for one disabled consumer may not be right for another. Similarly, what works in one area of rural Scotland may not in another. Person centred, place-based and community led approaches will be required to meet the needs of disabled consumers in rural Scotland.

We also note that addressing some of the challenges our report identifies may require financial investment, at a time where public and private resources are limited. Some potential solutions are less costly to implement but may instead require the implementation of a different approach or the capacity and willingness to think creatively. Whichever category a solution falls within, interventions will only be effective if disabled, rural consumers are involved from the start and included in their planning, design and delivery. Adopting an inclusive approach improves outcomes for all consumers.

Note on language and other key definitions

Consumers

Consumers are defined in Section 24 of the Consumer Scotland Act 2020 as individuals who purchase, use or receive in Scotland goods or services which are supplied in the course of a business. The definition of consumers in the Act includes small businesses, although for the purpose of this report our focus is primarily on consumers as individuals.

Disabled consumers

In this report we have chosen to primarily use identity first language and we refer to disabled consumers rather than consumers with a disability.[10] This identity first language reflects the social model of disability which recognises that people are disabled by their environment.[11] Where participants or stakeholders have a preferred terminology then we have used the terms they wish to use.

It is also worth noting that any reference to ‘disabled consumers’ includes consumers with a health condition. This includes consumers with physical and / or mental health conditions or illnesses that limit an individual’s ability to carry out day-to-day activities.[12] The Scottish Household Survey defines disability as a physical condition or illness lasting longer than 12 months. [13] Our analysis of the Scottish Household Survey 2022 data suggests that 26% (1,176,500) of adults in Scotland are disabled. It should be noted that this figure can vary depending on the design of the survey and the definition of disability used. The 2022 census found that that the percentage of people in Scotland reporting a long-term illness, disease or condition that has lasted or is expected to last at least 12 months was 21.4%.[14]

Rurality

This report uses the Scottish Government definition of rural areas as settlements with fewer than 3,000 people.[15] In 2021, 17% of Scotland’s population lived in rural Scotland, while rural areas accounts for 98% of Scotland’s landmass.[16] The Scottish Government’s ‘Urban Rural Classification 2020’ defines areas using an ‘8-fold’ classification system that ranges from ‘large urban areas’ to ‘very remote rural areas’. The relevant definitions of ‘rural’ for this report are the following:

- ‘Accessible Rural Areas’ – population less than 3,000 and within a 30-minute drive to a ‘Settlement’ of 10,000+

- ‘Remote Rural Areas’ – population less than 3,000 and drive time to a ‘Settlement’ of 10,000+ is over 30 minutes but less than or equal to 60 minutes

- ‘Very Remote Rural Areas’ – population of less than 3,000 and drive time to a ‘Settlement’ of 10,000+ is over 60 minutes

We refer to rural and island communities as ‘remote’ when using these definitions but not otherwise, noting that understanding and referring to rural areas as remote fails to take account of the fact that remoteness is relative and there are better ways to understand and describe rurality.[17]

Rural Disabled consumers

As shown in figure 1, our analysis of the Scottish Household Survey 2022 indicates that 228,900 (5%) Scottish adults live in a rural area and are disabled.

Figure 1

The proportion of adults in Scotland who are disabled and live in a rural location is 5%

Figure 1 Consumer Scotland Analysis of SHS 2022 data. Weighted proportions of Scottish Adults. Using the two-fold urban rural Classification (2020). Disability defined as a physical or mental health condition or illness lasting longer than 12 months.

5. The current evidence

In this chapter we summarise the existing evidence base on the experiences of disabled consumers living in rural Scotland in accessing transport, health and social care and leisure activities. We focus on recent evidence that relates specifically to Scotland and concentrate on issues relating to affordability, choice and accessibility. Where we have been unable to identify Scottish specific research, we have drawn on evidence at a UK level.

Overall, the evidence base provides a range of research on the experiences of disabled consumers or on rural consumers, but very little, if any, literature that explores both.

Affordability

Disabled people are more likely to have lower incomes and face additional costs

There is a significant existing body of evidence highlighting the substantial negative financial impact of being disabled. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2024) noted that in Scotland children and working age adults in a family where someone is disabled were three times more likely to experience combined low income and material deprivation and as a result are less able to access goods and services.[18] A rapid health impact assessment by Public Health Scotland (2022) also found that disabled adults in Scotland are more likely to be living in poverty and to have a higher cost of living than people living without a disability.[19] Similarly, analysis of the Family Resources Survey by the Equality and Human Rights Commission (2023) found that disabled adults in Scotland were more likely to experience worse living standards than non-disabled adults and were also:[20]

- Less likely to own property [21]

- Less likely to be in employment

- More likely to be in low paid or insecure employment

- More likely to earn a lower hourly wage

- Less likely to be in high paid occupations

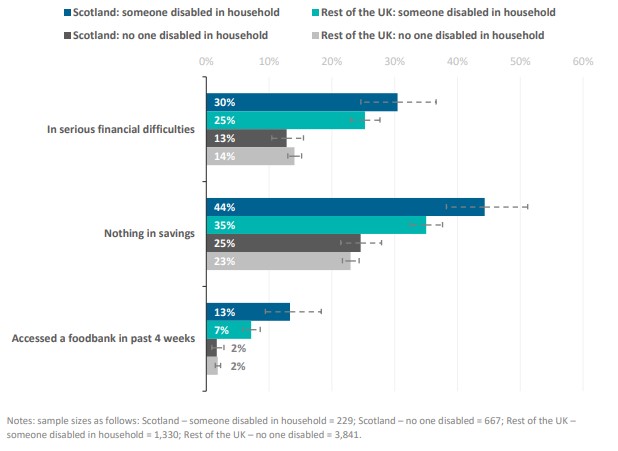

Recent research from abrdn Financial Fairness Trust (2024) also found that households including members who were disabled in Scotland fare significantly worse financially than households where no one is disabled (30% were in financial difficulty compared to 13%).[22] As shown in the figure below the same research also found that Scottish disabled households were “more likely to have nothing in savings (44%, cf. 35%) and to have accessed a foodbank (13%, cf. 7%) in the past four weeks than disabled households in the rest of the UK”.[23]

Figure 2

Percentage of households with poor financial wellbeing by disability status and nation (abrdn Financial Fairness Trust 2024 (p.18)

The literature highlights that despite being more likely to have a low income, disabled consumers often face additional costs. Disability Equality Scotland (2025) note that the additional costs experienced will vary from person to person and the impairments or health condition that they live with.[24] Some disabled people’s organisations, health charities and academics have attempted to quantify some of the additional costs faced by disabled consumers in the UK.[25] For example Scope’s (2025) Disability Price Tag report calculates that in 2024/2025 the additional amount of money a disabled household in the UK would, on average, require to reach the same standard of living as a non-disabled household is £1,095 a month. [26]

Consumer Scotland has previously highlighted how the increase in energy costs in recent years has disproportionately impacted disabled consumers who have high essential energy usage.[27] Our research found that disabled people are more likely to report a range of energy-related issues – including issues around energy affordability, debt, customer service and access to guidance from their supplier.[28] Evidence from other bodies also notes the disproportionate impact of high energy costs on disabled people.[29] Public Health Scotland’s review of evidence has highlighted how disabled people are more likely to live in homes with low energy efficiency and to be exposed to cold.

Consumers living in rural areas face a rural premium

The evidence base establishes that people who live in rural areas face a ‘rural premium.’ Affordability measures based on income often fail to take account of the higher cost of living in rural areas (Improvement Service 2024), while the average earnings of people who live in rural areas are likely to be lower (RSE 2023).[30] This is important to note because other evidence such as the tracker from abrdn Financial Fairness Trust (2024) suggests that households in rural areas perform better on indicators relating to financial wellbeing than those in urban areas.[31]

The Scottish Government has developed a Rural Scotland Data Dashboard and a Scottish Islands Data Dashboard which provide data on a range of issues that impact people living and working in rural Scotland and the islands. The dashboard includes data on how different costs impact consumers in these areas.

The most recent update (2025) to the Scottish Government’s research on the minimum socially acceptable budget for living in remote rural and island communities in Scotland calculated that the minimum financial uplifts households require to achieve a socially acceptable budget is between 14 and 30%, as shown below. The research highlights how additional costs vary depending on the type of goods and services, household composition and whether it is a remote rural or an island location.

Table 1 shows remote rural Scotland minimum budget uplifts from Scottish Government figures.[32]

Table 1

2023 Remote rural Scotland minimum budget uplifts by household category

| Household categories | Mainland | Island |

|---|---|---|

| Family with children, rounded uplift based on couple with two children | 14% | 14% |

| Working age rounded uplift based on average of single and couple | 26% | 30% |

| Pensioner rounded uplift based on average of single and couple | 23% | 24% |

Notably the largest additional costs faced by rural communities are additional motoring costs. The rural Scotland data dashboard (2023) highlights that the costs of both private or public transport are generally higher in rural areas, particularly for working age households and pensioners.[33] This is due to longer journey distances, greater reliance on cars, lower availability of public transport and higher fuel costs.[34] A Scottish Parliament Cross Party Group inquiry also noted that “for people living in rural Scotland, transport is the most significant additional cost compared to people living in urban areas, amounting to an additional £50 per week”.[35]

Public Health Scotland (2024) has highlighted that both those living in rural communities and disabled people are more likely to be impacted by ‘transport poverty’ defined as, “the lack of transport options that are available, reliable, affordable, accessible or safe that allow people to meet their daily needs and achieve a reasonable quality of life.”[36]

Travel is by far the greatest contributor to additional costs for consumers living in rural Scotland, compared to urban consumers. Public Health Scotland also highlight how around 50% of rural residents spend over £100 a month on fuel compared with 39% of people in the rest of Scotland and that a similar pattern is observed for public transport costs. They also estimate that weekly travel costs are up to 251% higher for pensioners living in remote rural areas on the mainland.

In relation to energy, rural and islands consumers also face higher costs. Many of Scotland’s rural areas are not connected to the gas network and rely on other types of heating (e.g. electricity, oil) which are more expensive (RSE 2023). Rural properties are also on average, both larger and less energy efficient than those in urban areas (Scottish Government 2023).[37] Fuel poverty levels therefore are higher in rural areas (Scottish Government 2025).[38] The Scottish Government estimates that 35% of households were fuel poor in rural areas in 2022 compared all Scottish households (31%) and urban households (30%). The rate of fuel poverty for remote rural households was even higher at 47%.

Choice

Fewer public transport options lead to greater reliance on cars

The geography of rural areas can result in a greater dependence on car use by rural consumers, as public transport or active travel provision does not meet their needs.[39] There are generally fewer public transport services than in urban areas, while services that are scheduled, particularly buses, are more likely to be susceptible to reliability issues.[40]

Satisfaction with public transport is much lower in accessible rural (46%) and remote rural (47%) areas compared to large urban areas (72%) (Scottish Government 2025).[41] As a result, consumers in rural areas are more likely to be dependent on private car ownership, lifts from friends and family or taxis. The costs associated with this can lead to significant affordability challenges.[42] These limitations in provision can also restrict consumers’ choices about when to access key services, such as in-person medical appointments, to times when public transport is running.[43]

These issues can disproportionately impact disabled consumers who may be more likely to require access to health appointments and other specialist support. Such services may be some distance from their homes, and local transport options may also have low service levels or accessibility barriers which can make the standard of services for disabled consumers “unacceptably low”. [44]

Health and social care is not always available in rural areas

The picture in relation to the availability of health and social care in rural areas is mixed. Some statistics suggest that healthy life expectancy is greater, waiting times to speak to a GP or nurse are lower and that the quality of care experience can be significantly higher in remote rural areas than the Scottish average (Scottish Government 2025).[45] Satisfaction levels with health and care services are broadly in line with those in urban areas. (Scottish Government 2023).[46]

However, a recent Scottish Human Rights Commission (2024) report relating to the Highlands and Islands said:

“Critical concerns over the lack of locally available services in certain areas of the Highlands and Islands. This often results in people having to travel great distances to access both basic and more complex health services. Some of the services where there are concerns about sufficient availability include: general practitioners, dentistry, orthodontic services for children, sexual and reproductive health services, mental health services, out-of-hours services, ambulance services, opticians, and drug and alcohol support.” (p.51)[47]

Given disabled consumers can be more likely to need to regularly access health and social care the impact is likely to be greater. The Equality and Human Rights Commission (2023) found that disabled people are more likely to have both unmet care and support needs and to be unpaid carers.[48] Disabled people in Scotland also experience lower collective wellbeing and mental health (Carnegie UK, 2024).[49] Carnegie UK (2023) also found that poor mental ill-health was significantly more common among disabled people than non-disabled people (31% compared to 6%).[50]

Leisure opportunities are more limited in rural areas

Access to leisure for disabled people is crucial for equality, inclusion, and wellbeing. Both the Scottish and UK Governments are signed up to the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). The UNCRPD sets out a number of rights that should be afforded to disabled people, including ‘living independently and being included in the community.’[51] The UK and Scotland have, however, been found to be failing to uphold these rights upon review.[52]

Previous studies have found that there are insufficient accessible leisure facilities in Scotland,[53] while the availability of leisure opportunities is especially lacking in rural areas.[54] Adults in rural Scotland reported lower levels of attendance at cultural events than those in the rest of Scotland (67% compared to 75%) in 2022. [55] A Scottish Parliament Cross Party Group report found that leisure opportunities were among the services that are most lacking in rural areas.[56] The report found this was in part due to a lack appropriate transport links, including for island residents who may have to travel by ferry to the mainland to engage in specific leisure activities.

In research commissioned by the Scottish Government (2024), some respondents from rural and island areas described having limited access to local cultural opportunities. The impact of weather on transport options and the additional costs of travel and accommodation were both highlighted as barriers. Rural respondents also flagged that the seasonal nature of provision can mean that in winter, there are fewer leisure opportunities. Limited digital connectivity was also an issue identified as impacting their ability to participate. [57]

Cultural attendance is also lower amongst disabled adults compared to non-disabled adults (56% compared to 80%)).[58] While attendance rates are much lower, the differences in participation in leisure activities between disabled adults and non-disabled adults is only slightly lower (72% compared to 76%).[59] Reading was the activity with the highest participation rates amongst disabled adults.

There are also reports which examine access to physical activity for disabled people in Scotland.[60] These show high numbers of disabled people in Scotland struggling to undertake physical activity, despite wanting to be more active, and note that many are reliant on family and friends to help them undertake activity when possible.[61]

Being digitally connected is increasingly essential for enabling choice

While digital participation will not be appropriate for all consumers, for many it is essential to access goods and services. Where health conditions impact on people’s ability to carry out everyday activities, this can lead to a reliance on the internet for accessing goods and services, as well as leisure and contact with friends and family (Ofcom / Blue Marble 2025).[62] Audit Scotland (2024) have highlighted how digital inclusion is vital for wellbeing and social inclusion.

“Being digitally connected can reduce social isolation for people already facing disadvantage, allowing them to be connected to family and friends, the wider community, and services. Examples of targeted support that enables digital inclusion are growing. Person-centred support can have a positive impact on people who are the most socially excluded. People with learning disabilities, older people and homeless people are all at greater risk of social isolation but can benefit when they are supported to use digital tools and technology” (p.26) [63]

Scotland is the most poorly connected of the UK’s four nations and rural communities are particularly affected by this (Ofcom 2024).[64] While progress is being made, rural consumers may experience lower connectivity speeds for broadband and mobile technologies, with 79 per cent coverage of superfast broadband in rural Scotland compared to 99 per cent in urban areas.[65]

Accessibility

Being able to access to transport is essential for rural and disabled consumers

Issues with the accessibility of public transport are an ongoing barrier for disabled consumers across Scotland.[66] Recent Consumer Scotland research reported that 38% of disabled people and those with long-term health issues found accessibility to be a barrier to choosing public transport.[67] These barriers can take physical forms, but other barriers also exist including poor information, a lack of onboard announcements, the poor levels of support from staff, and difficulty moving to and between stopping places, especially between different legs of journeys.[68]

There is also evidence of a range of challenges associated with transport services connecting people to healthcare locations, including issues around convenience, consistency, availability and affordability.[69] Poor information and a lack of support to identify and book travel can significantly affect the accessibility of transport to health options. The need to pay upfront for travel before being reimbursed, or a lack of ability to reimburse travel companions can lead to affordability barriers for some disabled people. The Scottish Government has committed to a number of measures to address issues in accessing transport to healthcare, though is not yet clear what impact these measures are having.[70]

As highlighted above the availability of digital services in rural areas is an issue for many consumers, but there are also specific issues around the accessibility of these services for disabled consumers. Levels of digital exclusion are high amongst disabled people, with Ofcom reporting that 51% of those who do not use the internet at home or elsewhere are disabled people.[71] A lack of appropriate support to access the internet and online services can make it harder and more time-consuming to complete tasks, leading to greater fatigue, anxiety and stress for disabled consumers.[72] For others, poorly-designed or confusing websites and forms can trigger anxiety and mental health problems. As a result, some prefer using face-to-face or telephone contact over digital services.[73]

Research has also highlighted a number of accessibility issues regarding attendance at cultural events. The Scottish Government’s (2024) research has highlighted a perception that “disabled people are excluded from many opportunities. This is because it is assumed too difficult and/or expensive to make certain activities or venues inclusive for different needs” (p. 30)[74]

Lack of evidence: Intersectionality

Our review suggests that there is a lack of evidence specifically on the experiences of disabled people who are also living in rural areas in Scotland. Inclusion Scotland (2023) have noted, “bespoke research in the standard of living of disabled people in rural locations and the specific challenges they face is lacking.[75]

One of the few examples where both rurality and disability have been considered in tandem is the Scottish Government’s analysis of the 2020 Scottish Health Survey which found that “the proportion of disabled people in urban and rural areas varies, but does not appear to vary consistently with the level of rurality in which individual lives” (p. 4).[76]

Few other examples exist where the relationship between these characteristics is examined in depth. The Equality and Human Rights Commission’s (2018) “Is Scotland Fairer” report highlighted that one of the reasons for this limited analysis of intersectionality is a lack of data relating to protected characteristics in administrative data sets, resulting in an incomplete picture.[77] Their most recent report (2023) again stressed that small sample sizes, different approaches to definitions or a lack of available data continues to limit the ability to examine how a combination of different characteristics may intersect.[78]

Summary

Our initial review of the evidence suggests that some of the challenges consumers living in rural Scotland face in relation to transport, health and social care and leisure are similar to those faced by many disabled consumers in different geographies. These include issues relating to affordability, choice and accessibility.

However, the way in which individual disabled consumers experience these issues is likely to vary depending on the nature of their disability or condition and their location, as well as multiple other factors. Detriment is also not necessarily experienced lineally and multiple disadvantage occurs in different ways. In the next chapter we set out our research approach to exploring these issues in more depth.

6. Methodology

In this chapter we describe our overall methodological approach to this work. We first commissioned qualitative research to ensure that the lived experience of disabled consumers living in rural Scotland was placed at the centre of this work. Our report draws on the voices of research participants throughout.

We have also undertaken in-house secondary analysis of large survey data sets to complement our qualitative research. This allows us to situate the in-depth lived experiences of consumers within in broader context, to facilitate a better overall understanding of the situation for disabled rural consumers. We have engaged with a number of key stakeholders including Disabled People’s Organisations and those representing consumers with health conditions throughout. We also consulted with Consumer Scotland’s Advisory Committee on Consumers in Vulnerable Circumstances. This chapter describes the approach taken to the qualitative research and the analysis we have undertaken. The key findings are set out in the next chapter.

In October 2024 we commissioned qualitative research from Thinks Insight and Strategy (Thinks) on how living in rural communities in Scotland can impact disabled consumers’ experiences in terms of their ability to access consumer goods and services and participate in everyday activities.

The overall objectives of the research were to:

- Identify what key issues disabled consumers living in rural Scotland experience and how this impacts on their ability to participate effectively in everyday activities and consumer markets

- Understand what the key priority issues are for disabled people living in rural Scotland in relation to improving their ability to participate in everyday activities and consumer markets

- Provide opportunities for disabled consumers to contribute to how these issues could be addressed by policy makers and organisations

Qualitative research methods facilitate an in-depth exploration of issues, generating rich insights to help inform understanding. We wanted to ensure that the research reflected the lived experience of disabled consumers living in rural Scotland. We worked collaboratively with Thinks, stakeholders and disabled consumers using an approach based on the ‘Social Model of Disability’.

It is important to note that the experiences of disabled people living in rural areas will vary considerably depending on the nature of their condition and where they live. An individual’s experiences will be driven by their specific needs and beliefs and can be highly individualised in terms of how it is experienced and its impact. Our purpose was to increase the existing evidence base on the range of different experiences, opinions and perspectives and provide recommendations to policy makers in Scotland to support action on the identified issues.

The Social Model of Disability

Consistent with the social model of disability of “nothing about us without us” the lived experience of disabled consumers living in rural Scotland was essential. We worked closely with Thinks to ensure that lived experience was central to the research design. Using the social model means that we identify challenges as arising from societal barriers not from an individual’s impairment or disability.

Research design: Qualitative research

The qualitative research was designed using the approach set out below:

A case study approach was taken focusing on two different local authority areas - Dumfries and Galloway and the Highlands. These areas were carefully selected to represent distinct areas of Scotland (the Southwest and the North of Scotland), as well as the inclusion of an island community (Skye). Both locations encompass a spread of accessible rural, remote rural and very remote rural areas using the Scottish Government classifications.[79] Selecting two different areas ensured we could explore a broad range of consumer experiences and draw comparisons about how these might be similar or different to one another where appropriate.

Whilst many of the learnings of this research could be applied for consumers across rural communities in Scotland, we have also noted that individual communities will have distinct features which may impact the needs of consumers living there. For example, the bridge connecting Skye to the mainland provides a convenient transport link – which is not the case for other island communities.

Our initial review of the evidence base identified a range of sectors and markets that could be examined in depth. Thinks worked with four stakeholder organisations and four disabled consumers in the case study areas to identify three priority markets that these participants felt were most important to the research. This is either because these were regarded as having a particularly significant impact on disabled people’s lives in Scotland or are under-researched. The areas agreed are set out below and informed the focus of Phase 2 of the research:

- Transport

- Health and social care

- Leisure activities

Phase 2 consisted of:

- A one-week diary exercise where the 34 participants reflected on their experience as consumers in the three priority sectors and

- Either a one-to-one online interview or an in-person focus group in Dumfries and Galloway or Skye

Phase 3 followed the analysis of the interviews and focus groups. In this phase we provided the initial key findings to participants and invited comments and feedback to ensure that our conclusions and recommendations resonated with their experiences.

The sample

Overall, 34 disabled participants were interviewed as part of this research, as well as four stakeholder organisations. Individual participants were recruited to ensure representation of consumers living with a variety of disabilities and their specific experiences, including participants with long-term health conditions, sensory impairments, learning disabilities, mobility issues and mental health conditions. While some participants received support from carers (at home and in the community) this was a minority of the sample. It is important to note that the majority of participants shared that they have multiple conditions, and research by the World Health Organisation (2023) shows that disabled people are doubly at risk of having or developing further physical or mental health conditions.[80] Carnegie UK (2023) also found that poor mental ill-health was significantly more common among disabled people than non-disabled people.[81] The total sample number in the ‘disability’ category in the table below is, therefore, more than 34, reflecting the fact that disabled people often have overlapping conditions.

Table 2

Sample overview

| Sample by location, rurality and disability | ||

| Location | Dumfries and Galloway | 13 |

|---|---|---|

| Highlands | 11 | |

| Skye | 10 | |

| Rurality | Accessible rural | 7 |

| Remote rural | 7 | |

| Very remote rural | 20 | |

| Disability | Mobility impairment | 10 |

| Sensory impairment | 7 | |

| Mental health condition | 19 | |

| Learning disability | 6 | |

| Long term health condition | ||

The sample was intended to represent the diversity of experience of disabled consumers living in rural Scotland. The research also sought to achieve a spread of gender, age and type of disability in the sample. Our review of the existing evidence in Chapter 2 highlights how disabled people are often on lower incomes. It is notable that while the inclusion criteria did not exclude those on higher incomes, none were recruited.[82]

A key part of the research design was ensuring that all participants could take part in a way that suited them. Thinks made the following arrangements to support this:

- To ensure the research was inclusive of those who are digitally excluded or live in areas with poor internet coverage, they offered a choice of online or telephone interview for the virtual interviews. For those living in Dumfries & Galloway and Skye, they also offered the opportunity to take part in an in-person focus group.

- Participants were given the option to complete their one-week diary exercise either online, through a paper version sent to their address or through sending a voice note via WhatsApp, according to their needs or preferences.

- An Easy Read version of the diary task and ‘check in’ task was created for participants with learning disabilities.

In addition, all participants were compensated for their participation in line with Scottish Government guidance.[83]

Note on analysis and the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

The data was analysed using thematic analysis. Researchers took notes during interviews and workshops, summarising key themes and noting down verbatim quotes. For completeness, the majority of interviews and workshops were also audio recorded. Following fieldwork taking place, data was inputted into a thematic ‘grid’ to allow for robust analysis of key themes, including similarities and differences between groups. This analysis grid was revisited regularly throughout the research and subsequent reporting phase to ensure findings reflected participant views and experiences.

The human analysis process was complemented by use of CoLoop, a specialist AI tool designed to support with analysis of qualitative research. All participants provided the appropriate consent for transferring a recording of their interview to CoLoop. The AI tool was used by Thinks as a complementary tool to sense-check key findings and themes and was not used as a replacement for manual, researcher-led analysis.

For this research, CoLoop was used for the following purposes:

- Delivering automatic transcriptions of recorded interviews and workshops. These transcriptions were quality checked by a member of the Thinks research team

- Supporting with the organisation of raw data into a qualitative analysis framework, e.g. providing an initial summary of key themes, linked back to source data to allow for quality assurance

For further information on the methodology see the final report from Thinks that is published alongside our report.[84]

Scottish Household Survey analysis

We undertook internal quantitative analysis using data from the Scottish Household survey. The aim was to identify how, if at all, the intersection of rurality and disability impacts the experiences of consumers when controlling for other inequality categories such as age, gender or socioeconomic status. Intersectional research has a history in the qualitative tradition but there is a growing body of research that attempts to quantify intersectionality using regression modelling techniques (e.g. Evans et al. 2018; Bell et al. 2019). The concept of intersectionality has had cross-disciplinary success and has been applied with multiple theoretical perspectives; however, there is no consensus about how it should be considered, conceptualised and applied. Our analysis is therefore exploratory and aims to complement the qualitative research.

We present stacked bar charts that illustrate a descriptive analysis of the proportions of respondents in each category by rurality and disability status. To test for statistical significance (p<0.05) we used order logistic regression for ordinal variables, logistic regression for binary variables, and OLS regression for continuous variables. For each outcome, we estimate four models:

- Model 1 included one independent variable with four groups (Disabled urban, Disabled rural -reference group, Nondisabled rural, Nondisabled urban)

- Model 2 added demographic controls: age, gender, income, number of children, number of adults, household head employment status, and off-grid status

- Model 3 used two variables - disability and rural residence - plus an interaction term, allowing the effect of disability to differ between urban and rural areas

- Model 4 replicates Model 3 and adds the same demographic controls as Model 2

This allowed us to consider the separate and combined impacts of being disabled and living in rural locations on outcomes net of other demographics.

7. Key Findings

Introduction

This section sets out the key findings from the qualitative research and data analysis of the Scottish Household Survey. It starts with a summary of the themes identified and then considers in more detail the barriers in relation to transport, health and social care and leisure in terms of availability (choice), cost (affordability) and inaccessibility. It concludes by considering how rurality and disability may compound to create disadvantage. A full report on the research findings by Thinks can be found here.

Figure 4

Key themes from qualitative research with disabled consumers in rural areas

Access to transport underpins many of the issues disabled consumers face in rural areas

Access to transport is essential to allow disabled consumers in rural areas to participate fully in their communities and to access goods and services. Participants highlighted how access to reliable, cost effective and accessible transport underpinned nearly all the challenges they experienced in accessing other goods and services. The knock-on effects of an inaccessible, unreliable, costly transport system were reflected by every participant.[85] Transport using private vehicles is the preferred option for many participants. The need for door-to-door travel, together with reliability and accessibility concerns, often prevented research participants from even attempting to use public transport.

Quote from participant in Dumfries & Galloway: “If you have a doctors’ appointment or whatever – you need to be there at a specific time. In the country you need wheels, it's not a luxury.”

Quote from participant in Participant in the Highlands: “Life would be impossible without [private] transport – my husband and I both drive. It’s a necessity for me, but it’s difficult and I can’t drive like I used to.”

Disabled consumers in rural areas experience constant and overwhelming anxiety about access to services

One of the most notable findings from the research was the psychological impact on disabled consumers in rural areas of dealing with issues relating to the unreliability, cost and inaccessibility of services. Many of the examples of lived experience cited throughout this report highlight the high levels of anxiety participants live with day to day due to their experiences of being disabled and living in a rural community when trying to access transport, health and social care and leisure.

The anxiety and stress caused by this unpredictability and the fear of potential adverse consequences often put participants off using public transport or accessing health or leisure activities at all. Many spoke about the anxiety of being left in a place that was unsafe for them or where they had no place to sit. They also worried about how they would be able to adapt their journey if something went wrong, particularly when, for many, active travel to reach a safe interim destination was difficult or impossible, due to the nature of their condition or the surrounding terrain.

Participants highlighted therefore the significant planning burden they faced as disabled people living in rural areas when seeking to simply access transport, leisure or health and social care. Life can lack spontaneity due to the need for planning, and reliance on family and friends.

Quote from participant in the Highlands: “Because my partner does so much for me, it often feels like I can't ask him to take me to do something fun, like to go and see a friend or to do something frivolous […] I don't have the ability to spontaneously do anything when I'm having a good day.” Participant in the Highlands

While accessibility can often be interpreted simply in terms of physical barriers, the research highlighted the mental health impacts caused by the constant and overwhelming anxiety and stress experienced by our participants. This impacted decision making whatever the nature of the disability or condition, compounding the challenges they faced.

The three key barriers of availability, cost and inaccessibility

The barriers to disabled consumers in rural areas accessing transport, health and social care broadly fell within the following three areas.

- Availability (Choice)

- Cost (Affordability)

- Inaccessibility

The separate and cumulative effects of these barriers mean that disabled participants face significant challenges when seeking to use transport, health and social care and leisure activities.

Availability – “it doesn’t work for people like me”

Participants reported that the availability of transport, health and social care and leisure activities differed, sometimes significantly, based on which parts of rural Scotland they lived in. There was a feeling that this amounted to a ‘postcode lottery.’ In some cases where consumers did not have access to appropriate transport links, they could find it difficult or impossible to access the services they wanted or required.

Quote from participant iin Dumfries & Galloway: “There's a little bus that comes on a Wednesday. It goes once a day at 9am and comes back at 3pm […] It doesn't work for people like me.”

Quote from participant in the Highlands: “Buses may not arrive, leaving me stranded, and I often have to rely on friends or taxis to get home, which can be costly and inconvenient.”

Participants perceive there to be fewer health and social care services than there used to be. Those requiring specialist care often struggled to access it without having to travel long distances. Many participants also reported difficulties in accessing dental services, in line with other research on this topic.[86] In relation to leisure activities, many participants reported that there were not many leisure opportunities. The relative lack of available transport options also exacerbates the availability of leisure options.

Quote from participant in Skye: “When we first moved here, the only dentist we could register with was in Kyle, which again is on the mainland… That's now closed, and I'm on a waiting list for the local dentist [so I’m unable to receive routine dental care at the moment].”

Quote from participant in Skye: “I have a friend who lives about four doors down from me who hasn't been able to come home from hospital because there are no care workers who do home visits. He's been stranded in Portree Hospital for months now because there are not enough carers in the community.”

Some services may not be available when consumers need them or want them, including being more restricted at certain times of the day or year. For example, some participants reported that, especially during peak tourism seasons, different services could be busier, more expensive, or less available.

Taxis, as well as being seen as expensive can be difficult to get at peak times in rural communities, particularly during the school run. Stakeholders made this point to us too. Participants who rely on taxis to travel discussed how they must plan ahead in order to avoid peak times.

Quote from participant in Dumfries & Galloway: “There aren’t many taxis in the area, and they mostly do the school runs.”

In relation to accessing health and social care and leisure activities, participants reported that it was often hard to line up different appointments with each other, or their travel arrangements. This could leave people either stranded in places for long periods of time, or unable to attend appointments or events later in the afternoon and into the evening.

Quote from participant in the Highlands: “There is public transport from my doorstep... but what it can't do is get me into town for a morning appointment and then back again in the afternoon. It would be a whole day activity to go to a one-hour appointment."

Quote from participant in Skye: “[The service] is 40 odd miles away and given the nature of the buses … that four-hour window is how long I'm stuck [there] regardless of when the appointment is. So, if I have to go for a 10, 15-minute appointment, it's four hours out of the house… What do I do with myself for the other three and a half hours?”

This would be inconvenient for any consumer, but for disabled consumers, this can have specific implications related to their health. Participants reported the longer waiting times or periods of inactivity can increase feelings of exhaustion and discomfort, and flare-ups of chronic pain. In some cases, this means increased distress for disabled consumers if the service they are accessing is essential. Some consumers may not feel able to access or attend certain services even if they would like to.

Quote from participant in Skye: “I don't want to be sitting in a car for six, seven hours a day going backwards and forwards to see my rheumatologist.”

Quote from participant in Dumfries & Galloway: "I haven't actually been able to go [to the dentist] for a year and a half now because patient transport won't take me and trying to get there is real hassle. My dentist is in Lockerbie, the only NHS dentist that will take me on… Now I've had dental pain since about 2016. I think they think that it's not that bad because I'm not making the effort to get there. But the effort to get there is actually more than the dental pain.”

Quote from participant in Syke: “I get very fatigued, and the cold can flare up my conditions. If I go in [to town] and miss the bus, then it’s an hour before the next bus comes.”

Cost “It's very stressful because you're having to budget”

Participants highlighted the financial impact that the cost of accessing transport, leisure and health and social care services was having them. In relation to transport, participants highlighted that public transport can be expensive, particularly when booked at the last minute. Rail travel is a particular example of this. Taxis are also considered to be very expensive, especially given their limited availability at certain times. For many participants, this effectively prices them out of being able to use taxis or means that they can only be used very sparingly.

Quote from participant in the Highlands: “The prices [of trains] are ridiculous if you don’t do it ahead of time. There are times where there are only two carriages, and they try and stuff everyone in, so booking a seat is a must.”

Quote from participant in Dumfries & Galloway: “It might be that you have to try and get a taxi from the hospital [if you don’t drive]. Dumfries [hospital] has a taxi stand, but that will cost you, 40, 50 quid or more.”

Quote from participant in Dumfries & Galloway: “Going up to Lockerbie you have to get cabs, country roads aren't easy. You don't realise how remote we are. Taxis are really expensive – £25-30 a trip”

While transport via private vehicles was the preferred option for many participants, the upfront cost of purchasing a car as well as the costs of maintaining the car, insurance and fuel were all barriers to accessing this form of transport. Participants also describe saving several tasks to do in a single trip to avoid wasting fuel, which can require prior planning and mean there is a delay accessing the goods and services they need. Whilst this may reduce costs, spending a long day completing multiple errands and/or attending appointments can exacerbate health conditions or lead to flare-ups for those living with chronic pain and result in extreme fatigue for the following 24-48 hours.

Quote from participant in Dumfries & Galloway: “If we have to go somewhere, we’ll think about other things we can do at the same time […] We always do a few jobs [in one journey] rather than just one.”

Participants highlighted the variety of additional costs they were likely to incur when accessing health care services which were located at a significant distance from their homes. These include costs associated with the transport to get to health services, with having long wait times (since they may need to wait around for long times in cafes as the transport links are infrequent) and in some cases accommodation. Some participants reported being able to claim back travel or accommodation costs but noted that recovering this money was retrospective, impacting their day-to-day budgets.

Quote from participant in the Highlands: “It's very stressful because you're having to budget, you know, you might have to do without something so you can pay the £16 to go to the hospital and then have to wait to claim it back.”

Quote from participant in Skye: “I needed surgery three years ago and I had to go to Aberdeen for that. So, it's a whole day to get there, a whole day travelling back. And you need accommodation – and yes, you can claim your accommodation [back], but you need that outlay initially.”

There are limited leisure opportunities that are free or low-cost. Given the affordability challenges that disabled consumers are more likely to face, many feel the need to seek out free or low-cost activities to engage in. Participants reported that of the limited leisure options available to them, even fewer were available on affordable terms.

Quote from participant in Skye: “A lot of things that happen don’t happen in our village – it’s a small village […] Lots of events and things, the cinema, are in Portree, but the last bus is at 6 at night. So for evening things, we would need taxis which are expensive, or to go with someone who’s driving.”

Rigid booking and payment terms can make leisure activities financially unsustainable for disabled participants. Where there is a requirement for an up-front payment for a block of sessions, the cost can be unaffordable and can also unfairly impact on disabled consumers who are more likely to experience health-related flare ups and be unable to attend.

Quote from participant in the Highlands“It’s the cost of it – you commit to a 6-week class and you only manage to turn up for three […] So the cost of attending things when everything is far more difficult financially [is a challenge].”:

Affordability challenges can often make spending on leisure ‘the first thing to go.’ This can restrict people, and especially disabled people, to leisure activities they can do at home, such as watching TV or puzzling, which can have the effect of increasing isolation and loneliness. Disabled people in Scotland already report much higher levels of loneliness than the reported average, and so access to leisure opportunities can be important to their wellbeing.[87]

Inaccessibility “It’s really frustrating”

A number of different challenges relating to inaccessibility were highlighted. Wheelchair users continue to experience distinct challenges with private and public transport. Participants who use wheelchairs report using public transport infrequently, with some saying they actively avoid using it as wheelchair spaces and/or ramps to board and disembark may not be available. For some, this is based on personal experience, whilst others have heard about this from peers and have been dissuaded from even attempting to use public transport.

Quote from participant in Dumfries & Galloway: “[I’ve] given up using public transport. Very few are wheelchair accessible, and even then, they are very infrequent.”

Quote from disabled consumer in Dumfries & Galloway: “They [buses] will just drive by because they know that there’s no way you could get on them.”

For those who use private vehicles, challenges with blue badge parking can significantly impact their ability to get where they want to, when they want to.

The experience of disabled people in relation to inaccessibility varies depending on the nature of their condition, which may include chronic pain, respiratory difficulties, learning disability, mental health issues, or a combination of them. Examples highlighted by participants were the inability to access public transport services in the tourist season, being unable to sit with a carer on public transport, or the need to plan journeys to ensure access to toilet services.

Quote from participant in the Highlands: “I generally need to be driven to appointments. The bus ride's only an hour, so it's quite possible that I would cope with that, but having [limited] access to toilet facilities is kind of tricky.”

Even when public transport itself is accessible, living in a rural area can make it challenging for disabled participants to reach the bus stop or train station without getting a lift or a taxi there. Some participants report that even taxis won’t always take them ‘door-to-door’ if they live in a particularly rural location – for example, at the end of a long road, dirt track, or driveway. This can be especially problematic for those with mobility issues who can struggle to get to their door.

Quote from participant in Dumfries & Galloway: “Even if I did get a taxi, they would refuse to go up our track. [In the past] I’ve had to wait for my dad to drive down a rough track for a taxi to then pick us up, it's just not a reasonable option. It's really frustrating.”

Quote from participant in Dumfries & Galloway: “We live at least a mile away on a rough lane from the nearest bus stop. The buses are fairly infrequent, they’re just not practical to use.”

Participants were generally clear that the outdoor spaces in rural areas were something they valued, and the opportunity to get out in the fresh air is a really positive element of rural life. However, it is still the case that many outdoor rural spaces, including dedicated leisure spaces, are not accessible to many disabled consumers. Those with mobility issues, breathing problems (i.e. COPD) and chronic pain in particular report that they often aren’t able to take part in outdoor activities. Uneven terrain, a lack of paved pathways and a lack of places to sit and rest along a path make it challenging for participants with these types of conditions to engage in active travel and explore the outdoors in their area. Being unable to participate in outdoor activities also has an impact on mental health.