1. Introduction

Consumer Scotland has been invited by the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero to respond to the UK Government’s consultation on the proposed amendments to Sizewell C Limited’s (SZC’s) electricity generation licence.

2. Background

Consumer Scotland is the statutory body for consumers in Scotland. Established by the Consumer Scotland Act 2020,[1] our Purpose is to improve outcomes for current and future consumers. We are independent of the Scottish Government and accountable to the Scottish Parliament. Our core funding is provided by the Scottish Government, but we also receive funding for research and advocacy activity in the electricity, gas, post, and water sectors via industry levies which are derived from consumers’ bills.

Our responsibilities relate to consumer advocacy. In our 2023-2027 Strategic Plan,[2] we have identified three cross-cutting consumer challenges, which guide our work during this period. They are:

- Affordability

- Climate change mitigation and adaption

- Consumers in vulnerable circumstances

Consumer Scotland welcomes the opportunity to contribute to this consultation. We are pleased to provide one part of the necessary input on the interests and protections on behalf of consumers.

This is the first response by Consumer Scotland on the UK Government’s proposals for the use of a Regulated Asset Base (RAB) model to support the financing of new-build nuclear power generation in Great Britain. Recognising the broad experience of economic regulation in the UK, Consumer Scotland acknowledges and shares the view of Ofgem that “RAB models can be an efficient way to finance large scale infrastructure projects such as water and electricity networks”.[3] Nevertheless, this will only be achieved if the incentive structure of the RAB model is designed and implemented effectively.

We recognise in full that the UK Government has made a clear commitment to proceed with this approach, subject to appropriate decision making processes under the terms of the Nuclear Energy (Financing) Act 2022.[4] Our comments are – in principle – neither in favour nor opposed to nuclear power, or to the use of a RAB model to support nuclear investment. Consumer Scotland has no statutory role in the decision making on nuclear projects in Great Britain. We note the Scottish Government is opposed in principle to new build nuclear power generation in Scotland “using current technologies”.[5]

To guide our response to this consultation, we have utilised our Consumer Principles. These are based on frameworks that have been developed over time by both UK and international consumer organisations. Reviewing policy against these principles enables the development of more consumer-focused policy and practice, and ultimately the delivery of better consumer outcomes.[6] The Consumer Principles are:

- Access – can people get the goods or services they need or want?

- Choice – is there any meaningful choice?

- Safety – are consumers adequately protected from risks of harm?

- Information – is it accessible, accurate, and useful?

- Fairness – are goods and services detrimental or inequitable to individuals or groups of consumers?

- Representation – do consumers have a meaningful role in shaping how goods and services are designed and provided?

- Redress – if things go wrong, is there an accessible and simple way to put them right?

- Sustainability – are consumers enabled to make sustainable choices?

Our response therefore focuses on the design, efficiency, and effectiveness of the economic regulation of SZC, as established through the proposed Generation Licence[7] – taking into account the statutory objectives in the legislation.[8] Our concerns relate to the risk allocation between taxpayers, investors, and consumers; and to ensuring that the protections for consumers are as robust as possible.

Dr. Simon Gill of The Energy Landscape provided expert advice on the development of this response.

3. Consultation Process

On 6th November 2023, the UK Government published an open consultation on “Modifications to the Sizewell C Regulated Asset Base licence”.[9] On the same day, we received a formal letter of invitation to respond to the consultation from the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero. This included a copy of the Price Control Financial Model (PCFM), which gives effect to the proposed licence conditions. As requested in the letter, we have considered the consultation document in conjunction with the PCFM, the “draft electricity generation licence: special conditions for nuclear generator”,[10] and the “Guidance on our approach to the Economic Regulation of Sizewell C”,[11] published by Ofgem.

The consultation document sets out the scope of the consultation process and explains the particular role requested of Consumer Scotland. Overall, the consultation is part of the statutory process set out in the Nuclear Energy (Financing) Act 2022.[12] In particular, it seeks to fulfil the requirement on the Secretary of State to consult on the modifications to the Generation Licence of the designated nuclear generator (in this case, SZC), which in turn provide the framework to ensure value for money and an acceptable risk allocation between consumers, taxpayers, and investors.

The consultation sought views on the consumer and public interest from Citizens Advice for England and Wales and Consumer Scotland for Scotland. As outlined in the consultation document:

“the Secretary of State has decided not to consult with the general public. Instead, consumer groups will be consulted allowing expert input that will reflect the interests of the public. This decision was based on the highly technical nature of the modifications”[13]

Consumer Scotland would like to see the UK Government move beyond this “highly focussed”[14] approach. Notwithstanding the important contribution that Consumer Scotland and Citizens Advice can make, there is significant scope for engagement by and for consumers in this process. We acknowledge the UK Government has undertaken previous consultations on the RAB model, and that the parliamentary process leading to the Nuclear Energy (Financing) Act 2022 has provided opportunities for public comment. Moreover, we readily acknowledge the highly technical nature of the licence modifications. However, a sufficient consumer voice cannot be provided by our two organisations alone.

The importance of safeguards for consumer interests is important in all areas of economic regulation, but is especially important in the nuclear RAB model. This approach is substantively different to the Contracts for Difference (CfD) type approach employed for projects such as Hinkley Point C, and changes the allocation of risk between taxpayers, investors, and consumers. The CfD approach seeks to “price-in” future risks and provide a degree of protection that future consumers will not be required to fund cost overruns beyond those which have been priced-in. However, given the nature of nuclear investment risk, it is recognised that the level and complexity of assurance required by investors is such that a CfD type approach may not represent good value for consumers; alternatively, that investors may be dissuaded from investing in the project at all. The RAB model therefore shifts some of this investment risk onto future consumers by establishing a regulatory mechanism to require future consumers to fund a share of increased costs, which under the CfD model would have been entirely faced by investors. It is argued that this approach could reduce the overall cost to consumers (particularly through a lower cost of capital), and importantly provide sufficient reassurance to investors to enable them to invest.

When compared with the well-established mechanisms for the protection of taxpayer and investor interests, the mechanisms for protection of consumer interests under a RAB model appear more limited. For example, the interests of taxpayers will be protected through the multi-layered internal processes of government, including the internal scrutiny in Departments; by the UK Treasury; and importantly, by the well-established process of Accounting Officer assessments. Likewise, the interests of SZC and its investors will be served by their advisers and due diligence processes. At present however, the consumer appears to be facing significantly greater risk, with limited assurance around governance, scrutiny, and visibility of decision making on their behalf.

We therefore strongly recommend that before making final decisions on the licence modifications, the UK Government broadens and deepens the range of contributions from consumers and from consumer organisations. Given the special characteristics of the nuclear RAB process, it should be the responsibility of the UK Government, the licensee, and the economic regulator to nurture an informed and technically literate engagement with this process.

In the immediate future, this engagement would be required to enable the Secretary of State to have due regard to the interests of current and future consumers when determining the final modifications to SZC’s Generation Licence, including in the setting of important regulatory parameters. More widely, the licence modifications and the economic regulation of SZC would benefit from greater engagement with consumer interests.

As an example, the regulatory Guidance issued by Ofgem[15] increases our confidence that Ofgem will discharge its duty to represent consumer interests. The Guidance highlights Ofgem’s statutory duties and typical regulatory processes – for example, referencing the RIIO-ED2 process used for setting the electricity distribution price control between 2019 and 2022.

Given that the Secretary of State, not Ofgem, is responsible for much of the regulatory process between now and the Final Investment Decision (FID), and throughout the pre-Post Construction Review (pre-PCR) phase of the project, we would like to see similar principles and processes laid out by the Secretary of State.

4. Consultation on the Generation Licence Modifications

The consultation initiated on 6 November 2023 seeks input from consultees on the five areas set out below, but is not limited to these questions:

- Do consultees consider that the licence modifications outlined within the consultation strike a reasonable balance between the need to support the financeability of the licensee and safeguarding consumer interests?

- Do consultees consider that the incentives and penalties placed on the project through the modifications will support the efficient and timely delivery of the project, ensuring greater value for money for consumers?

- Do consultees consider that the operational performance incentives included in the proposed modifications encourage the right behaviours?

- Do the modifications set sufficiently clear expectations and boundaries for how the project company should operate in the market over time, and do the modifications contain sufficient flexibilities to account for future uncertainties in the energy market?

- Do consultees think that the modifications provide Ofgem sufficient oversight in its capacity as economic regulator of the licensee?[16]

As far as possible our response takes into account the previous consultation processes on the nuclear RAB model, and in particular the Guidance published by Ofgem as noted above. It also acknowledges that the UK Government has given commitments that further information will be made available when the final licence modifications are published and the FID is made. This will include an assessment of value for money prepared by the UK Government.

Overall, our initial assessment is that the proposed licence modifications and related documentation do not provide sufficient institutional and regulatory safeguards on consumer interests.

In this response we have identified some suggested modifications to the draft licence and some high level principles that we would like the UK Government to consider to address some of our concerns.

However, it is beyond our remit as a consumer advocacy organisation to make specific counterproposals or to seek to draft suggested replacement text. Moreover, our concerns are not limited to these specific areas. The breadth of our concerns is also likely to require further modifications to the licence and in the procedures of decision making by the UK Government and Ofgem in particular.

Scotland specific considerations

Scotland forms part of the wider electricity system in Great Britain, and responsibilities for legislation and regulation of the sector are reserved to the UK Government and Ofgem. As such Scotland is treated in the same way as any other part of Great Britain. However, there are a number of characteristics of consumers in Scotland that are relevant to any assessment of the distributional impacts of introducing a RAB model for new-build nuclear power generation in Great Britain.

Typical energy consumption values, calculated by Ofgem, suggest that an average household in Great Britain uses 2,700 kWh of electricity and 11,500 kWh of gas.[17] In households that use electric heating, the majority of this gas use is transferred to electricity.[18] Average electricity use in homes with dual-rate metering (typical of those with storage heating) is 44% higher than in households with single-rate metering.[19]

Due in part to its climate, Scotland has a higher median level of domestic heat demand[20] despite dwellings which are, on average, more thermally efficient than a typical property in either England or Wales.[21],[22] The population of Scotland is also older,[23] and in less good health,[24] than the Great Britain average – both of which are markers of enhanced heating need.[25] Scotland also has a greater prevalence of traditional forms of electric heating than the Great Britain average.[26]

Taken together, these attributes mean that consumers in Scotland will, on average, use more electricity and will make a larger contribution to costs levied on bills on a per-unit basis than their equivalents elsewhere in Great Britain.

Under current market arrangements, electric heating users are considerably more likely to be fuel poor in Scotland compared to users of other heating fuels.[27] Additional levies on electricity bills would serve to increase detriment amongst an already financially vulnerable consumer group. Consumer Scotland’s energy tracker survey has repeatedly shown that electric heating users are more likely to report struggling to keep up with their energy bills when compared to other households – 37% of electric heating users reported struggling compared to a 30% average in the tracker’s autumn wave in 2023.[28]

5. Question 1: Do consultees consider that the licence modifications outlined within the consultation strike a reasonable balance between the need to support the financeability of the licensee and safeguarding consumer interests?

The nuclear RAB model offers the prospect that by introducing an explicit risk sharing formula, and by allowing investors to start realising a return on their investment from day one, the return on capital required by investors in new-build nuclear power generation in Great Britain will be lower, and funding will be more likely. The UK Government has assessed that the nuclear RAB model will therefore make it more likely that a nuclear project will proceed, and that this lower return on capital will deliver savings for consumers (when compared to the funding model used to support Hinkley Point C).

Consumer Scotland acknowledge that a RAB type model could provide an efficient and effective way to take forward complex and risky infrastructure projects. There is potential to create a risk sharing framework that finds a “reasonable balance” between the interests of consumers, taxpayers, and investors. But a RAB type approach will only be successful if the design of the regulatory framework is sufficiently robust to match the scale and complexity of the project, and there is sufficient information to make that judgement.

As currently proposed, we have significant concerns that consumer interests will not be sufficiently protected – particularly in the setting of important regulatory parameters which will only be determined alongside the FID. Overall, our initial assessment is that as they stand today, the proposed licence modifications and related documentation do not provide sufficient institutional and regulatory safeguards on consumer interests.

The proposed licence modifications create a bespoke framework of economic regulation for SZC, including a project-specific framework for the allocation of risk between investors, taxpayers, and consumers. Through the licence, SZC will be provided with unique privileges as an electricity generator and substantial recourse to future consumers in the event of cost overruns, delays in the project timetable, lower performance, etc. This differs from other electricity generators (and from Hinkley Point C), where these categories of risk are faced by investors.

As published, the draft licence modifications provide important safeguards and a comprehensive set of special conditions. They appear to provide extensive safeguards to protect the interests of taxpayers and investors, which may make the FID more likely. But we are concerned that this will be achieved by shifting risk too far onto the shoulders of future consumers, with inadequate transparency and institutional safeguards of their interests.

Our view is that any RAB model which places a greater burden of risk onto future consumers should in turn include greater transparency, scrutiny, and institutional safeguards to protect consumer interests. Taken together, the draft licence modifications do not yet provide us with the necessary assurance that the interests of consumers will be sufficiently protected.

In particular, the initial regulatory parameters set by the Secretary of State will be the single most important component of the “reasonable balance” between the respective interests of consumers, taxpayers, and investors. The most important of these parameters will be set when the final licence modifications are published and the FID is made. Consumer Scotland is concerned that the pressures to set these parameters at a level which meets the interests of investors and taxpayers will be such to produce a questionable outcome for consumers.

It is imperative that the process and principles by which these parameters will be set is transparent. There are many examples of good regulatory practice, where decision makers set out principles and guidance on how decisions will be made and how decisions have been taken. The Guidance prepared by Ofgem alongside this consultation[29] is one such example.

We recommend that, through the licence conditions themselves and through separate publications, the Secretary of State lays out the specifics of how consumer interests will be considered and reported on, including a process of reporting how those principles impact on the setting of key regulatory parameters.

Introduction

Our response sets out our understanding of how the financial aspects of the regulatory framework will work in practice, including the implications for current and future consumers.

The RAB model significantly reduces risk for investors in the Sizewell C nuclear power station project, and for SZC as the developer / operator. It passes much of that risk to consumers and taxpayers:

- Risks associated with relatively likely contingencies, such as construction cost overruns and future electricity price variations, are passed to consumers

- Risks associated with low probability-high impact events, such as more extreme cost overruns or a significant future ‘change of law’ banning nuclear power, are passed to taxpayers through the Government Support Package that sits alongside the RAB framework

The UK Government has argued that this is necessary to realise the stated policy objective to enable further nuclear power developments to take place in Great Britain. Specifically, it has been stated that:

“it is clear that if any model is to attract private financing it will likely require:

- A variable £/MWh price allowing for the revenue stream to be adjusted by the Regulator as circumstances change

- An Allowed Revenue during construction to reduce the scale and cost of financing, increasing deliverability and reducing total cost to suppliers and consumers

- Some level of risk sharing between investors and consumers / taxpayers”[30]

The UK Government has determined that a CfD model is no longer suitable for new-build nuclear power generation facilities in Great Britain. It has argued that the financing costs (i.e. the cost of capital) required to entice investors would be very high, and/or that funding would be unavailable at the scale required. It has also highlighted that in the case of Hinkley Point C, which was developed on a CfD type approach (albeit without a competitive auction), the level of the strike price doubled between the start of negotiations in 2012 and the point at which the CfD contract was signed in 2016.

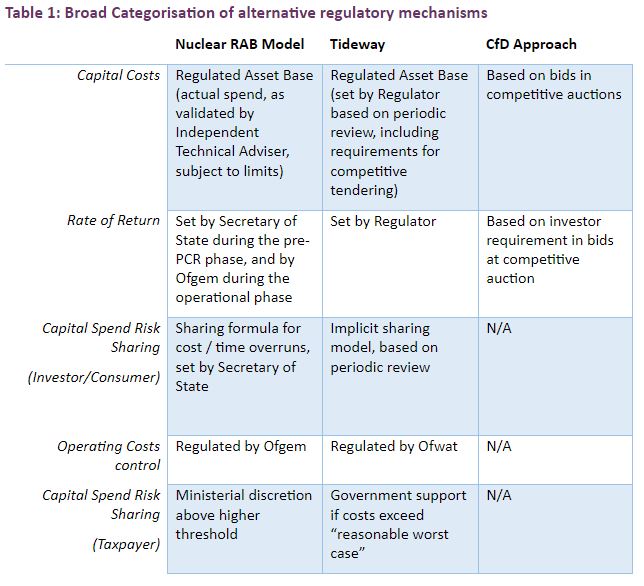

The UK Government has set out some of the similarities between the nuclear RAB model and the model utilised to develop the Thames Tideway Tunnel. Table 1 provides a summary of these different regulatory arrangements for risk sharing. Although there are similarities, Consumer Scotland notes that there are some important differences between the Thames Tideway Tunnel model and the nuclear RAB model being proposed.

The essence of the UK Government’s case for using this approach is that the special characteristics of nuclear investment make it unlikely that private investment will be secured under a CfD type approach. By way of comparison, under a CfD type model there is no regulatory mechanism to share the risk of cost overruns, and therefore no lower or higher cost thresholds to which investors are exposed. Consumers are therefore protected from cost overruns, and cost risks lie entirely with investors. However, in negotiating the CfD strike price, investors are likely to “price-in” some cost overruns and demand larger returns on their investment due to the significant risks they are taking on. While CfD type models therefore have considerable attractions in reducing risk to future consumers, this is achieved with an increase in the rate of return for investors.

Consumer Scotland acknowledges that a different risk allocation model for new-build nuclear power generation in Great Britain could – in principle and in theory – deliver positive outcomes for current and future consumers. The arguments have been set out in previous consultations; in particular, in the Impact Assessment[31] prepared by the then Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy during the passage of the Nuclear Energy (Financing) Bill in 2021, and in the Secretary of State’s designation of SZC in November 2022.[32] We also note the arguments laid out by Professor David Newbery on the cost of capital under various regulatory models,[33] and the contributions of Professor Dieter Helm on the cost of capital[34] and in his Cost of Energy Review in 2017.[35]

We welcome the UK Government’s publication of analysis to underpin its decision making, including the Impact Assessment published in 2021 as part of the parliamentary process.[36] We also note and welcome the publication of the Accounting Officer’s Assessment of the Sizewell C decisions, published in June 2023.[37]

However, we would like to see these documents updated and enhanced. In particular, we are concerned that the economic assessment remains limited in scope and based on illustrative costs and forecasts, rather than actuals. The Impact Assessment which underpinned the legislation, the Accounting Officer’s Assessment, and the designation decision by the Secretary of State were all based on a counterfactual where alternative options to proceeding with a nuclear project were utilised, rather than a full economic appraisal which included an assessment of the value for money of proceeding with a nuclear option at all. We note that recent increases in interest rates, which many expect to represent a longer-term change, may impact on the most cost effective means of achieving a just transition to Net Zero.

We are concerned that there is very limited publicly available information on the likely costs of the Sizewell C development. The UK Government’s latest published assessment of levelized costs of electricity generating sources was published in November 2023.[38] It notes that:

“Nuclear costs are revealed through bilateral negotiations which relate to specific projects. Project-specific analysis is used to inform the Government’s approach to these negotiations. Because the information and analysis used for this purpose is commercially confidential, it is not available to be used to update our generic cost assumptions”.

Given the importance of protecting consumer interests, the level of visibility of these cost assessments should be improved. There is an opportunity and need for the UK Government to make a full assessment available alongside the final licence modifications.

The importance of the initial Regulatory parameters

The final generation licence will include certain parameters (which will be agreed between the UK Government and SZC) which will establish the overall sharing of risk between investors, taxpayers, and consumers:

Regulated Asset Base (RAB). During construction, the actual, out-turn capital spend on allowed expenditure will be measured and validated, and added to the RAB. SZC will be able to earn a return on this RAB during the pre-PCR phase and recoup any remaining allowable costs during the operational phase based on a formula set out in its licence. The level of the RAB will be set at the PCR by Ofgem three years after operations at the plant have commenced and will then be depreciated across the operating lifetime of the project, allowing SZC to recoup its investment from consumers.

The Initial Weighted Cost of Capital (IWACC). This is the rate of return that will be set by the Secretary of State in the final licence modifications and will be applied throughout the pre-PCR phase. It will be replaced with the Real WACC (RWACC), set by Ofgem, during the operational phase.

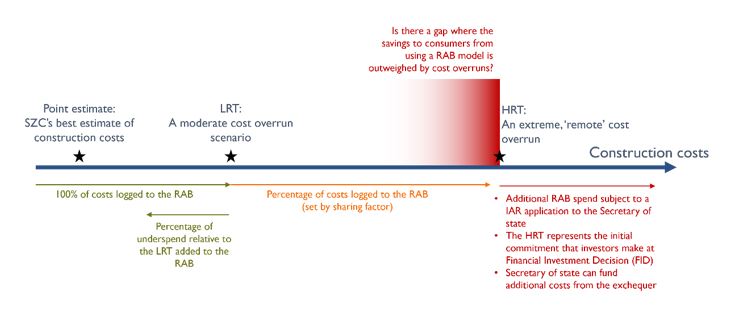

Lower Regulatory Threshold (LRT). This will be an initial estimate of the capital cost of the project, including an allowance for “moderate cost overruns”, set by the Secretary of State in the final licence modifications at the point of the FID. The company will be able to earn a return (and recoup costs from consumers) on 100% of the RAB incurred up to this level. If the actual capital spend exceeds the LRT, SZC will be able to add half of the further spend to the RAB up to the HRT (see below). If total construction costs are less than the LRT at the end of the pre-PCR phase, 50% of the underspend relative to the LRT is added to the RAB. This mechanism establishes a risk sharing mechanism between investors and consumers.

Higher Regulatory Threshold (HRT). This is an estimate of the upper end of the project’s capital costs and is set by the Secretary of State in the final licence modifications at the point of the FID. It will be set at a level reflecting “a significantly remote scenario above the licensee’s view of an extreme outturn cost.”[39] In the event that the RAB substantially exceeds the LRT, this higher threshold sets an upper limit on the risk sharing arrangements for the RAB. It therefore places a cap on the risks facing consumers. The licence modifications set out mechanisms for the Secretary of State to take steps to approve further increases in the RAB and/or introduce further taxpayer funding to moderate the financial pressures on investors and consumers through the Government Support Scheme.

The central argument for utilising the nuclear RAB model for new-build nuclear power generation in Great Britain is that consumers (and taxpayers) will benefit overall from the use of a risk allocation formula set out in the generation licence rather than pricing-in risk at financial close, as is the case in a CfD type model; it is argued that the overall benefits of a significantly lower cost of capital will more than offset the very significant and uncertain “contingent liabilities” that the formula imposes on future consumers. As outlined above, we acknowledge this argument in principle, but we are not assured that there are sufficient safeguards for consumers in practice.

Assessment of “Reasonable balance”?

A RAB framework appears to be broadly appropriate in principle and could work well in practice. It puts in place the structures to provide cost and risk sharing: incentives, caps, longstop dates on construction, etc. However, the ultimate balance of risk and reward between investors, taxpayers, and consumers is heavily dependent on key parameters that have not yet been set.

Therefore, at this stage, Consumer Scotland’s view is that there is significant risk that the final package does not deliver good value to consumers. This is because critical parameters are still under negotiation between the Secretary of State and investors, and because that process does not include a clear route to ensure consumer interests are appropriately represented.

The main parameters will only be set at the point of the FID, and our assumption is that at that point will be contractually set in stone. Notwithstanding the current consultation process on the terms of the licence modifications, we are concerned that there will be insufficient public scrutiny of the process of decision making on the setting of these parameters.

Information asymmetry has long been identified as a significant challenge for economic regulation. It refers to the fact that the developer or operator of a regulated asset has significantly better understanding of the costs, risks, and other factors than the regulator. In reference to energy networks for example, information asymmetry is known to incentivise network owners to push for higher than required investment costs ahead of an ex-ante regulatory settlement, to maximise the return received as they outperform the settlement during the price control period.[40]

The most important point at which information asymmetry could be seen in the case of Sizewell C is in the setting of regulatory thresholds ahead of the pre-PCR phase. There is a strong incentive on SZC and investors to inflate their estimate of construction costs where this has the potential to impact on some of the Regulatory parameters:

The LRT is defined in the consultation document as including “moderate cost overruns”. If outturn capital costs are below the LRT, any underspend – subject to the finally agreed sharing factor – can be added to the RAB. Therefore there is a strong incentive on SCZ to push up the level of the LRT.

The IWACC sets the rate of return on the RAB throughout the pre-PCR phase. There is a strong incentive on SZC to push up the IWACC.

It is less clear what the incentive is in terms of setting the level of the HRT: there could be an incentive on SCZ to push up the HRT if investors still see the sharing factor as favourable, given the low level of risk provided by the RAB model and the fact that they may need to continue funding the project above the HRT with zero investment added to the RAB. This would be the case if:

a)the Secretary of State were unwilling to approve an Additional Allowable Spend application; and

b)the Secretary of State did not decide to use taxpayer funding to continue the project; and

c)SZC and its investors wanted to complete the project in order to continue realising a return on their initial investment.

The current consultation defines the framework for the RAB, including the CAPEX incentive and return on capital building blocks. However it does not set key regulatory parameters: the LRT, HRT, sharing factors, or the IWACC. These are critical parameters in deciding whether the proposal represents a good deal for consumers.

The consultation document states that the “IWACC is determined by the Secretary of State prior to license modification” and that “the LRT and HRT are set by the Secretary of State at FID in real terms”.[41]

However, it is unclear:

a)how this decision will be reached, or what information will be used to set the IWACC and the LRT; and

b)the degree of scrutiny that will be applied to the setting of the IWACC and the LRT – for example, whether it will be consulted on or whether there will be other opportunities for consumer representatives to comment.

Concerns about the process for setting the regulatory parameters

The relatively limited information which is emerging about the setting of the main parameters increases rather than decreases our concerns. The decision making by the Secretary of State on these key parameters will have to find a “reasonable balance” between the interests of consumers and the interests of investors. The role of Ofgem and the Secretary of State in setting and managing the RAB framework has the potential for significant tensions. The aim is to balance the interests of both investors and consumers. In common with many regulatory frameworks, this puts Ofgem and the Secretary of State in the dual role of both consumer representative and arbitrator between investors and consumers.

In energy network regulation this is managed by setting up a detailed regulatory framework based on a clear set of principles and a strategic narrative or strategy. Decisions are made through a clear, predefined, and transparent process in which decisions are justified through reference to the principles and strategic narrative. Examples include Ofgem’s regulatory stances[42] and strategic narrative,[43] which supplement Ofgem’s strategic duties. Similarly, in the water sector in England and Wales, Ofwat regulates according to a set of principles[44] and a regulatory strategy.[45]

In the current draft licence conditions it is clear that there is an important decision making role for Ofgem in the operational stage of the RAB model, beginning with the PCR. We strongly welcome the publication by Ofgem of its “Guidance on our approach to the Economic Regulation of Sizewell C”.[46]

The incentives facing SZC and its investors will be to seek to maximise the LRT, the costs of capital, and the Sharing Factor as far as possible. The interests of consumers are likely to be best served by lower levels of these parameters.

The interests of consumers and investors are more complex with regard to the setting of the HRT. Depending on decisions by the future Secretary of State, taxpayers may be exposed to the risks of cost overruns once the HRT is reached. The interests of taxpayers may be best protected by setting this threshold as high as possible.

The licence modification provides some evidence of the current thinking in setting these levels. The consultation document states that the Secretary of State will set these parameters utilising information made available by SZC:

“The Secretary of State is expected to set the LRT at a point above the target outturn cost, and the HRT at a significantly remote scenario above the licensee’s view of an extreme outturn cost”.[47]

This statement carries important implications:

a)Firstly, we are concerned with the incentive structure implicit in setting the LRT above the target outturn cost. This will mean that the full amount of any capital spend over and above SZC’s own ex-ante assessment of its target outturn will be eligible for addition to the RAB.

b)Secondly, we are concerned with the statement that the HRT will be set at an even higher level than SZC’s own assessment of an extreme outturn cost. This means that the point at which the Secretary of State is asked to review cost-sharing arrangements and to consider taxpayer contribution will be beyond what SZC regards as a remote and extreme cost overrun. We think, in terms of governance, that a control point – allowing for Government intervention or adjustment, or regulation of further spending – would be required well before this threshold is met.

c)Thirdly, in terms of exposure of consumers to higher bills, setting the HRT at a very high level locks in consumers to fund a potentially significant proportion of allowable cost overruns.

We would like to see the UK Government publish some illustrative examples of how cost overruns would impact on consumer costs. This will help stakeholders understand the possible outcomes and impacts of changes to the RAB parameters.

On 23 January 2024, EDF announced an increase in costs and a further delay at Hinkley Point C.[48] Prior to that announcement, Hinkley Point C was due to begin operating in 2027, eleven years after the CfD contract was signed and at a cost of £25 billion – £26 billion (in 2015 prices).

The cost of Hinkley Point C is now expected to outturn between £31 billion and £34 billion, and operations are now not expected to commence until at least 2029. If similar cost overruns and delays were to arise under a RAB model, consumers would be liable to fund several billion pounds of further pre-operational costs as well as a proportion of the cost increases over the operational life of the station.

We note the concerns about intergenerational fairness that were raised by Citizens Advice in response to the UK Government’s 2019 consultation on introducing a RAB model for new-build nuclear power in Great Britain.[49]

We therefore recommend that the UK Government publishes examples for Sizewell C to support wider engagement with informed but non-expert stakeholders. These types of examples can demonstrate how far the regulatory parameters will find a “reasonable balance” between the interests of consumers, taxpayers, and investors. In our view, the UK Government should place a much higher priority on explaining and illustrating the choices being made which impact directly on consumers.

However, prior to that it is the Secretary of State that will make the key decisions on regulatory parameters during the lead up to the FID. We would like to see the UK Government articulate how it will consider consumer interests, by including principles and guidance on how it will balance the interests of investors, taxpayers, and consumers. The Ofgem Guidance is a helpful example of how this can be done. It is imperative that a clear articulation of regulatory principles is published, ahead of setting the final regulatory parameters.

We recommend:

Recommendation 1.1: The Secretary of State should publish a clear framework and set of principles defining how consumer interests will be considered during final negotiations, and publish comprehensive information on how these principles were implemented at FID.

Recommendation 1.2: The Secretary of State should give consideration to whether it is possible to implement a period of scrutiny of the final licence modifications, including the values chosen for key parameters, before the final licence modifications are set.

Recommendation 1.3: The Secretary of State should publish a comprehensive Economic Appraisal and Impact Assessment alongside the final licence modifications. This should:

be based on actual project information and the UK Government’s latest assessment of the future electricity market, rather than illustrative information as in previous assessments; and

include an economic justification of a nuclear investment compared to other options to achieve a just transition to net zero; and

include an economic appraisal of the final licence as a whole, including the values chosen for key regulatory parameters which demonstrates the value for consumers compared against appropriate counterfactuals; and

include a full proposal on monitoring and evaluation of the UK Government’s decision, as suggested in the Impact Assessment published during the parliamentary stages of the legislation.[50]

Recommendation 1.4: The LRT should be set as low as possible, whilst having regard to financeability and the agreed value of the IWACC. The HRT should be set with greater clarity of what risks future consumers may be required to take. The decision on the final values chosen for these parameters should be made using published, regulatory principles (see recommendation 1.1).

6. Question 2. Do consultees consider that the incentives and penalties placed on the project through the modifications will support the efficient and timely delivery of the project, ensuring greater value for money for consumers?

From the information available Consumer Scotland does not have sufficient assurance that the modifications will ensure efficient and timely delivery, or value for money for consumers.

There is significant evidence from existing nuclear power generation plants and ongoing nuclear power generation construction projects that show the majority overrun in terms of cost and time – often significantly. Whilst Sizewell C is expected to benefit from the learning acquired during the planning, authorisation, and construction Hinkley Point C, Hinkley Point C was not the first European Pressurised Reactor (EPR) to begin construction; similar projects are underway in both Finland and France, and all three have faced significant cost and time overruns.

We are concerned that the CAPEX incentive scheme rewards SZC for moderate cost overruns (i.e. those below the level of the LRT), rather than aiming to penalise all cost overruns. We are also concerned that there could be a gap between the cap on SZC’s costs (i.e. the HRT) and the point at which cost overruns outweigh the benefit to consumers of using a RAB mechanism.

We are concerned that the penalties for delay will not be set sufficiently high. We note that for commercial projects, and for those supported by CfD, there is no revenue until commercial operations begin. This provides a very strong incentive on the developer to minimise delays. Under the draft RAB licence we understand that in the event of a delay, consumers will continue to pay a return on investment however that return will be reduced relative to the IWACC. It is important that a meaningful penalty is applied so that it is both fair to consumers and provides a sufficiently sharp incentive to deliver on time. We are also concerned that the licence does not place limits on continued additions to the RAB in the case of an extreme time-overrun beyond the longstop date.

Introduction

Time and cost overruns will both lead to significant consumer detriment: cost overruns will lead to consumers paying more than expected through levies on their bills, while time overruns will leave consumers facing higher than expected electricity prices and without the benefit of a major component of the low-carbon electricity system. It is therefore critical that an appropriate incentive framework is put in place for the pre-PCR of Sizewell C. The framework must ensure clear motivation for SZC and its investors to manage costs and minimise delays. This is particularly important because, whilst construction risks are complex and large, SZC is the only organisation able to control and mitigate most of those risks.

There is the potential for significant cost overruns in relation to the construction of Sizewell C. This is clear from the recent global history of constructing new nuclear power stations and specifically projects related to the EPR design on which Sizewell C is based.

Cost efficient delivery

Reviews suggest the cost overruns for nuclear power stations have reached more than 100% of the initial estimates for a number of projects in the recent past.[51]

The cost estimate for Hinkley Point C, which has a very similar design to that expected to be used at Sizewell C, has risen from £16 billion in 2012, to £18 billion in 2016 (at the point of signing the CfD contract),[52] to between £25 billion and £26 billion in 2022, and to between £31 billion and £34 billion in 2024[53] (all in 2015 values). Recent projects using the same design in Finland and France have experienced cost overruns of three- and four-times initial estimates, respectively.[54]

The argument for RAB funding is predicated on the assumption that consumer savings due to reduced financing costs will offset even significant cost overruns. Analysis by the National Audit Office suggests that a reduction in the cost of capital from 9% to 6% could offset a cost overrun in the range 75% - 100% of the initial estimate.[55]

The HRT represents the upper limit on cost overruns that can be incurred without submission and approval by the Secretary of State of an “Increased Allowed Revenue” (IAR) application. The HRT plays a number of important roles. Firstly it places a limit on expenditure that can be added to the RAB under the licence; therefore it is an upper bound on consumer costs. Secondly, it provides a limit on investors’ commitments – investment at FID stage involves a commitment to spend only up to the HRT. Thirdly it allows the Secretary of State a number of options for continuing the project:

- by encouraging investors to continue funding the project but without additional spend being added to the RAB, in order to realise the value of their investment to that point; or

- by allowing further capital spend from investors to be added to the RAB (subject to investors submitting an IAR application); or

- by funding further work via Government (i.e. taxpayer) spending, funded from the Government Support Package

The consultation describes the HRT as a limit that is “at a significantly remote scenario above the licensee’s view of an extreme outturn cost.”

Consumer Scotland is concerned that setting a high HRT could mean that if construction costs do overrun to this level, the benefit to consumers of using a RAB mechanism to keep down the cost of capital could be outweighed by the costs faced by consumers from high cost overruns.

This point is illustrated in Figure 1: Relationship between cost estimates, RAB and regulatory thresholds

Figure 1: Relationship between cost estimates, RAB and regulatory thresholds

Penalties for time overruns

Overruns in time are likely to be intimately linked to overruns in cost. However, there will be additional consumer detriment. For the duration of the delay, consumers will receive less secure, higher carbon, more expensive electricity than would otherwise be the case.

For most electricity generators, no revenue is received before generation begins. A delay to commissioning a project therefore means a delay in the point when investors begin to see a return on their investment. One of the mechanisms by which a RAB approach brings down costs is by providing a return on investment ahead of the start of operation. However, this significantly reduces the incentive to deliver on time in comparison with a fully commercial or CfD funded project.

The RAB framework includes a penalty for delays beyond the scheduled commercial operations date (COD). The penalty is a reduction on the IWACC, applied from the target COD to the date at which COD is achieved. The mechanism also provides for a yield cap which limits the distribution of returns to investors for the four years after the target COD and a full “distribution lock up” for the remainder of any delay.

Whilst the yield cap and distribution lock up is important, it does not reduce the costs levied on consumers. The key parameter is therefore the penalty on the IWACC.

We are concerned that paying any return on investment during a period of delay represents a softening of the incentive that would apply to a commercial project or one supported by CfD mechanisms. We acknowledge the fact that the RAB model, including providing a revenue stream to investors ahead of the start of commercial operations, is an important part in keeping costs down; however, we recommend that UK government ensures that a sufficiently strong penalty for delay is applied.

The draft licence appears to apply a single penalty, in the form of a reduction to the IWACC, for any length of delay. However, longer delays could have larger impacts on consumers as wider developments across the energy system would increasingly have been planned on the expectation that Sizewell C was operational. Therefore, we think it is worth considering a tiered approach to delay penalties, with a higher penalty applied for longer delays.

Delays beyond the longstop date

The license indicates that SZC must achieve commercial operations ahead of the longstop date. However, the license does not include special conditions defining what would happen if commercial operation were not achieved ahead of the longstop date.

Instead, Consumer Scotland understands that SZC would be in breach of the licence and penalties would come from enforcement action by Ofgem under the Electricity Act 1989.[56] This action would follow Ofgem’s Enforcement Guidelines,[57] which include a series of steps that could ultimately result in a fine of up to 10% of annual turnover if Ofgem is satisfied the infringement was committed intentionally or negligently.

Consumer Scotland’s view is that consumer interests are likely to be better served by placing an explicit time limit on additions to the RAB; and by providing the Secretary of State with a “control point” with options to change the conditions for the addition of further spending to the RAB, or to consider the value in using Government funding for further investment. The longstop date should carry similar weight and lead to similar consequences as cost overruns that reach the HRT.

Consumer Scotland recommends adding an additional licence condition which applies a similar status to the longstop date as is currently applied to the HRT: if the longstop date is reached, the terms of the licence should set out that no further spend can be added to the RAB unless SZC submits an “increase in allowed time” application. This would play a similar role as the IAR does in relation to the HRT.

We recommend:

Recommendation 2.1: As part of the comprehensive Economic Appraisal and Impact Assessment (see Recommendation 1.2), the Secretary of State should prepare an analysis of the value to consumers that the RAB model delivers relative to a CfD model at a number of “cost overrun” scenarios. This should include delivery at the LRT, at the HRT and, if applicable, at the point between the two in which the benefit to consumers of the RAB model falls to zero.

Recommendation 2.2: The penalty for delay needs to be set sufficiently high to ensure both a strong incentive to SCZ to deliver on time and a fair outcome for consumers. This should take account of the fact that commercial and CfD supported projects would receive zero revenue ahead of the start of commercial operations, including throughout a delay. By contrast SCZ will continue to receive a return on investment from customer levies, reduced by the penalty applied. In order to reflect the increasing impact that an extended delay is expected to deliver, we also recommend considering a tiered approach where the penalty increases with longer delays.

Recommendation 2.3: The licence should disallow the addition of capital spend to the RAB after the longstop date. Allowed revenue on spending incurred after this date would only be authorised where an application to the Secretary of State was made and approved. This process would mirror the existing arrangements for cost overruns that reach the HRT.

7. Question 3: Do consultees consider that the operational performance incentives included in the proposed modifications encourage the right behaviours?

The operational performance framework laid out in the licence will not be implemented for more than a decade. For this reason, whilst the licence lays out the framework and sets some parameters to initial values, decisions on many of the regulatory parameters are deferred until the PCR and subsequent five-yearly periodic reviews. Consumer Scotland feels that this approach and framework is appropriate given that Ofgem intends to apply a rigorous regulatory process to determining the value of parameters and retains the right – if required – to adapt the framework.

In carrying out this role, we would expect Ofgem to apply its wider regulatory principles, narratives, and statutory duties to ensure that determinations are made in a clear, evidenced, and transparent way, following the best practice it currently uses in its network regulation.

We are concerned that the market performance incentives, whilst potentially sufficient to incentivise efficient trading of the output from SZC alone, could be insufficient when considering the impact on a wider trading portfolio. For this reason we recommend that the licence includes a formal requirement to ringfence trading of SZC’s output from trading of the output of other assets owned by EDF or other investors.

Operational incentive mechanisms and periodic review

It is reasonable for consumers to expect the highest standards of operational performance throughout the lifetime of Sizewell C in return for the substantial investment they are making in the project. In terms of performance, the license includes frameworks to incentivise availability and through-life capacity. It also chooses to apply an incentive to reduce TOTEX (total expenditure), rather than apply separate CAPEX and OPEX incentives.

These frameworks are linked to determinations that Ofgem will make at the PCR and subsequent periodic reviews. During these reviews Ofgem will set new values for regulatory parameters including the real WACC, target unit capacity factors (UCF) and TOTEX sharing factors. The full details of the parameters that will be set in the PCR are listed in Special Condition 43, and for the periodic reviews in Special Condition 58.

Ofgem has issued draft Guidance explaining how they will approach the regulation of SZC.[58] This includes references to its existing legislative framework, consultation policy, and good practice taken from its network regulation.

Consumer Scotland agrees that the broad framework for operational performance incentives can protect consumers, and that it is appropriate to defer decisions on key operational phase parameters until the operational phase itself.

We expect Ofgem to take a similar approach to determining the PCR and periodic reviews as it does for its current network price regulation. This includes setting out a clear process with draft and final determinations, and opportunities for a wide range of stakeholders – including consumer representatives – to engage, comment, and provide evidence to assist Ofgem in its decision making.

Whilst the framework appears appropriate, we would note that representing the consumer effectively in an area as technically complex as nuclear power is challenging. We are concerned that it may be difficult for consumer groups to challenge justifications made by SZC for underperformance and which may affect the determination of future price control periods. During the operational phase, there is no Independent Technical Adviser (ITA), and we suggest that the UK Government consider carefully how it will ensure sufficient technical understanding and resource is available to consumer representatives.

The risk of market power within the electricity market

Sizewell C is expected to be operated by EDF Ltd., who are also expected to partially own and operate Hinkley Point C along with a growing fleet of wind farms, solar farms, and short duration electricity storage projects in Great Britain. EDF is also a large electricity supplier in Great Britain.

In 2022 EDF had an 18%[59] market share in the electricity generation market as well as a 14% share of the domestic electricity supply market. Although all of EDF’s existing nuclear stations are currently expected to close by the early 2030s, from the late 2030s the combination of Hinkley Point C and Sizewell C could be as much as 14%[60] of current annual electricity demand. There has also been a recent suggestion from EDF that they could look to extend the lifetime of their existing nuclear fleet.[61]

The inclusion of a large RAB funded power station in EDF’s trading portfolio has the potential to influence the way that portfolio is traded in the wholesale electricity and wider energy markets.

The draft license includes a market price adjustment which delivers an incentive to trade power efficiently. The sharing factor for this mechanism will be initially set at the point of the FID and will be reviewed by Ofgem during the PCR and at subsequent periodic reviews.

This mechanism should provide sufficient incentive on SZC to achieve and, if possible, exceed the baseload market reference price (BMRP) – assuming that trading is optimised for SZC alone. However, there is a risk that, if traded as part of a wider portfolio, losses from underachieving the BMRP at SZC are offset by greater gains elsewhere in the portfolio.

Revenue streams for CfD renewables provide an example of a situation where complex interactions within a portfolio could lead to a misalignment of incentives. During periods of low market price it makes a significant difference to the revenue of CfD generators if the price is just below or just above zero. Since CfD allocation round 4 (AR4), no CfD difference payments are made to generators if the market reference price is less than zero. The operation of SZC, particularly in combination with onsite flexibility options such as hydrogen electrolysers and short duration electricity storage, could have the potential to influence the market price in a way that would have significant impact on revenues for EDF’s renewable fleet and outweigh any gains or losses from the SZC market price incentive.

Ofgem have existing powers to guard against wholesale market manipulation. However, the regulatory burden of proving instances of manipulation is high. For this reason, it could be of benefit to consumers – and helpful to Ofgem – to provide further protection beyond existing powers.

One approach to managing these risks is to ringfence the trading of power generation at SZC within EDF, or to require that an independent entity is put in place to trade the output from SZC. This would provide consumers with confidence that market power was not exercised and ensure that the incentives on SZC operate as designed, without interaction with wider “portfolio” effects.

We recommend:

Recommendation 3.1: The UK Government should consider carefully how it will ensure sufficient technical expertise and resource is available to consumer representatives.

Recommendation 3.2: The trading of SZCs energy market activity should be ringfenced. Ringfencing could be within EDF’s wider trading functions with a requirement to report on how independence is achieved, or by requiring the trading function to be delivered by an independent third party.

8. Question 4: Do the modifications set sufficiently clear expectations and boundaries for how the project company should operate in the market over time, and do the modifications contain sufficient flexibilities to account for future uncertainties in the energy market?

Over the coming decade there will be significant changes in the structure of the energy system and associated markets. Whilst the operation of nuclear power stations provides a useful baseload supply of electricity in today’s system, the value of doing so in a high-renewable, low-carbon electricity system in future could be much lower. As such, there is likely to be value in SZC being incentivised to be as flexible as possible in terms of its ability to generate electricity, its co-optimisation with other forms of flexibility such as short duration electricity storage, and its exploration of non-electricity energy markets.

Ofgem’s Guidance document[62] highlights the potential for the electricity market structure to change, and that the licence may need to be adapted to reflect those changes. As an example, the Guidance notes that the definition of the market reference price may need to change, or even that the concept of using a reference price at all may need to be replaced by an alternative approach.

Whilst the Guidance appears to be aware of the potential for changes to the electricity market, Consumer Scotland are concerned that the licence and Guidance give insufficient attention to the potential for non-electricity energy outputs to become a significant part of SZC’s revenue. This could be driven by reduced need for baseload electricity generation and/or the growing opportunities and scale of markets for low carbon hydrogen and/or heat. Consumer Scotland recommend that greater consideration is given to ensuring the licence is sufficiently flexible to deal with non-electricity revenue streams.

The value of flexibility

Nuclear power stations derive their revenue almost exclusively from the sale of electricity within the wholesale market. Traditionally they have operated as baseload, with a flat generation profile as close to maximum output as is technically feasible. There is some optimisation associated with the timing of maintenance and other outages, although this flexibility is somewhat limited by the regulatory requirements imposed by the Office of Nuclear Regulation (ONR) and in order to manage nuclear safety issues and carry out regular inspections.

The need for baseload electricity generation is reducing and it is expected that by the 2030s there will be significant periods of the year during which there is an excess of renewable generation available over and above that which can be used to meet demand, charge storage, or export over interconnectors. For example, a recent analytical illustration of a summer day in 2035 shows up to 19 GW of renewable generation required to turn off whilst baseload generation – nuclear in the example used in the illustration – must continue to operate.[63] National Grid ESO’s most recent Future Energy Scenarios suggest renewable curtailment purely due to an excess of renewables and baseload generation of between 38 TWh and 67 TWh in 2040 for net-zero compliant scenarios.[64]

During periods of excess supply from renewables the need for, and value of, baseload electricity will be minimal and potentially negative.

There are a number of options for how Sizewell C as a project can deliver flexibility:

a)the stations could be development alongside flexible technologies such as batteries and hydrogen electrolysis which are then operated to adjust the export of power from SZC to the grid.

b)flexibility in the project’s operational business model.

c)the design of the power station itself.

Interaction between the electricity market and wider energy market

By the time operations begin at Sizewell C there are likely to be alternative revenue streams available to electricity generators. For example, SZC’s generation could be used to produce heat and/or hydrogen rather than being exported to the grid.

The size of these alternative markets could be large, and there is the potential that, at least in some scenarios, a significant fraction of SZC’s revenue comes from non-electricity sources. For example, in National Grid ESO’s 2023 Future Energy Scenarios, hydrogen electrolysis capacity rises to 42 GW in the System Transformation scenario in 2040. This scenario includes production of 12 TWh of hydrogen specifically from nuclear-connected electrolysers in 2030, from a total hydrogen supply of 269 TWh.

The draft license does acknowledge the potential for multiple revenue streams, for example defining “Supplemental Revenue” as well as “Actual [electricity] market revenue”. However, the structure of the operational phase license conditions focuses primarily on the sale of electricity. For example, the “market price incentive mechanism” provides an adjustment relating to the difference between the actual electricity revenue compared with the expected electricity revenue.

A more flexible incentive would be one that compared actual and expected energy market revenue (which includes both electricity revenue and supplemental revenue) and would incentivize SZC to find any way to outperform the market reference price, but not just in ways that relate to trading electrical energy.

An alternative approach could be to continue to focus on electricity market revenues in terms of the core licence, reflecting the fact that difference payments are levied on electricity consumers (rather than consumers of hydrogen or heat), but to introduce an incentive mechanism which shares the revenue from non-electricity energy markets between SZC and electricity consumers.

The need for a pre-operational review

The points above highlight some of the significant uncertainties over the future electricity market and wider energy markets. This is crystallised in the current UK Government review of electricity market arrangements (REMA), which has the potential to significantly change the way electrical energy is traded in Great Britain. Options under consideration through REMA include a move towards locational prices, centrally dispatched wholesale markets, and loss of firm access rights for generators. This would significantly change the market structure in which SZC will operate.

Ofgem have noted the potential for major reform of the market and its impact on SZC’s licence. For example, they highlight that should the BMPR become unfit for purpose, they anticipate considering whether to amend the calculation of the BMPR, replace it with a different reference price, or replace the concept of a reference price with a different methodology.[65]

Ofgem goes on to say that the review of the reference price methodology will happen as part of the PCR. However, this is only due to take place three years after commercial operations begin. Whilst part of the period between the start of commercial operations and the PCR will be taken up with commissioning, there is significant potential for consumer value to be lost if the licence does not match the structure of the energy market during that period.

There are a range of other changes to the structure electricity and wider energy markets which could require alterations to the licence frameworks. The most obvious example is the potential, discussed above, for SZC to derive a significant fraction of its revenue from non-electricity energy markets.

In order to avoid a three year period where the licence does not fit with the prevailing energy market structure, we recommend that consideration is given to adding a “pre-operational” review, with the scope to adjust the licence to better align with the prevailing electricity market design and wider options for using SZC’s output.

We recommend:

Recommendation 4.1: The licence should be adjusted to better incentivise flexibility. It is important that this is introduced ahead of the FID to ensure that the incentive can affect the design of the project – including, for example, the addition and integration of on-site flexibility with the nuclear station itself.

Recommendation 4.2: The licence should ensure that there is a clear and fair incentive on SZC to maximise revenue in all available energy markets, including non-electricity energy markets.

Recommendation 4.3: A pre-operational licence review should be introduced ahead of the COD, with the scope to adjust the licence to reflect the prevailing energy market structures – including relevant non-electricity energy markets.

9. Question 5. Do consultees think that the modifications provide Ofgem sufficient oversight in its capacity as economic regulator of the licensee?

We support the significant role for Ofgem to regulate SCZ during the operational phase of the project and strongly welcome the Guidance published by Ofgem alongside this consultation.[66] A role for an independent economic regulator remains a vital safeguard to provide assurance to existing and future consumers in the utility sector across the UK. Ofgem’s expertise and statutory duties, especially their principal objective to protect the interests of current and future electricity consumers, put them in a strong position to take on this role.

We are however concerned that the role of Ofgem is circumscribed, and largely applicable only to the operational phase of the project. We would expect the independent economic regulator to play a larger role – as is the case with the RAB model used for the Thames Tideway Tunnel, which the UK Government has suggested is a relevant comparator. We think the circumscribed role for Ofgem in the initial phases of the project is not consistent with independent economic regulation of a RAB model.

The final licence modifications should include a much greater scrutiny role for Ofgem to enable them to have sufficient oversight over the whole lifecycle of the project. This would include providing some form of independent assessment of the setting of regulatory parameters and substantially greater role during the pre-PCR phase.

This enhancement of the role of Ofgem to provide sufficient scrutiny would require greater attention to the governance of, and transparency of the work of, the ITA. We recommend changes to the governance of the ITA, and mechanisms for greater transparency of decision making.

Introduction

There is and will be significant consumer and citizen interest in the development of the nuclear RAB model. The recourse to future consumers to help manage the risks of the project brings with it a greater need for transparency and visibility of decision making and the costs to consumers. This should be overseen by an independent economic regulator, and we support a significant role for Ofgem.

There are several people and entities whose role it is to represent consumer (and taxpayer) interests in the RAB process. These are:

- The Secretary of State for Energy, who is responsible for negotiating the support package which will deliver the investment needed. This includes both the RAB framework and the Government Support Package. In this role the Secretary of State will set the license conditions which form the basis of the current consultation.

- The Secretary of State for Energy will set a number of key parameters which will significantly affect the share of risk and reward between SZC and consumers. Several of these parameters are yet to be set, including the LRT, HRT, and the IWACC which sets the return on investment allowed throughout the pre-PCR phase.

- The Secretary of State for Energy is also responsible for deciding any applications for any IAR application which would enable SZC to log spending above the HRT to the RAB.

- Ofgem will be the economic regulator: working within their remit to represent the needs of consumers Ofgem will apply the license conditions, determine allowed revenues, and set the RWACC for the operational phase.

- The Independent Technical Adviser is a group of experts whose role is to provide independent scrutiny of SZC’s costs and make recommendations to Ofgem as to what costs should be logged to the RAB each year.

- The Low Carbon Contracts Company will be the Revenue Collection Counterparty; this is the organisation that holds the contract with SZC for the payment or recovery of difference payments. It will also calculate and collect levies from supply companies to fund the difference payments. It has a role in calculating difference payments based on forecasts of future electricity market prices and information provided to it by Ofgem, however its function is largely administrative.

Concerns about the circumscribed role for independent regulation

- In the draft modifications, the setting of initial regulatory parameters is entirely for the Secretary of State. We think that Ofgem should play a key role in the decision making process on the regulatory parameters and the UK Government’s endorsement of the project, and that this should be clearly set out in the licence. We are concerned that the Guidance published by Ofgem,[67] and its response to the UK Government’s consultation on the designation of SZC, confirm that Ofgem have “no formal role” in the assessment of value for money and no role to provide independent verification of the UK Government’s modelling. Ofgem’s response to the consultation on the designation of SZC made clear that:

“For the purposes of project designation and noting that we have no formal role in assessing whether the Sizewell C nuclear project presents value for money for consumers, Ofgem has not undertaken any assurance relating to BEIS’s modelling or analysis, nor otherwise sought to independently verify on behalf of BEIS whether project designation is likely to result in value for money for consumers.”[68]

We think Ofgem should have these roles, and that the role of Ofgem should be set out clearly in the licence modifications.

Ofgem should also have sufficient oversight of the pre-PCR of the project, in its role as an independent economic regulator. This is essential to provide assurance to consumers that the project is on track and that the regulatory thresholds are being effective during the pre-PCR to drive the right behaviours. Given the very significant risks that future consumers are being asked to take, we think it only right that consumers can look to a suitable role for independent regulatory oversight of the pre-PCR phase of the project.

We note the important role for Ofwat in the case of the Thames Tideway Tunnel. The UK Government has made clear that:

“in developing a potential nuclear RAB model, the Government has taken the model used for Thames Tideway Tunnel (TTT), as a starting point, whilst recognising that new nuclear projects are significantly greater in scale and cost, and face unique challenges, which are different from, and would not have been relevant to TTT”.[69]

Our view is that independent economic regulation of the pre-PCR is a fundamental requirement of a RAB model. We are concerned that the nuclear RAB model appears to limit the role of regulation too far in this phase, and instead relies almost wholly on the incentive mechanisms to ensure cost-effective construction.

There is not the provision in the licence modifications for a price control review before the PCR, which may well be 15 years after the project is initiated. Moreover, the Guidance published by Ofgem sets out its expectation that it will not make changes to the licence. It states that:

“Conditions we do not expect to change include the capacity targets, the Initial Weighted Average Cost of Capital (IWACC), the principles by which the nuclear licensee will be able to recover allowed revenue, the principles of the incentive mechanisms, and the protection against market movements in the cost of debt. There are also no Periodic Reviews prior to the PCR”.[70]

In effect, the risk-sharing mechanisms are set out in the licence modifications, with very limited scope for change to allow for appropriate scrutiny. We understand that these commitments to provide clarity and to limit the extent of regulatory intervention are likely to provide assurance to investors. But we are concerned that the licence modifications, and the scope for Ofgem to scrutinise their implementation, shifts the balance too far.

As an illustrative example, in the event that the project is subject to a substantial cost overrun, the licence modifications provide a secure mechanism for SZC to add further costs to the overall RAB and recoup these costs from consumers. So, if the capital costs of the project are £10 billion over the LRT, consumers will be liable to fund £5 billion of these costs. The draft licence modification does not include any additional mechanism for scrutiny and review of these costs, or assessment of whether they reflect unavoidable circumstances or managerial effectiveness.

In the event of such cost overruns, we would expect significant consumer and parliamentary interest in understanding the causes and explanations of the outturn. It does not seem credible that future Ministers would be able to rely on the licence modifications to argue that there is no role for the UK Government or Ofgem to scrutinise such an outcome. We therefore think it is in the interest of consumers – and indeed of taxpayers and investors – to consider how the operation of the licence would work under scrutiny in the future. This suggests further clarification of the role of Ofgem and the ITA.

In the draft licence, there is a clearly stated mechanism for the calculation and verification of the “allowable costs” incurred by SZC which can added in the calculation of the RAB. This is the key parameter against which the ultimate costs to consumers will be based. This number will be calculated and monitored by Ofgem, based on estimates provided to them by SZC and the ITA. The governance of this flow of information is set out in the licence.

We think this flow of information can and should be enhanced. At present, the formulaic mechanism to calculate the RAB is based on information provided by SZC and verified by the ITA. The consultation document describes this process as follows:

“The logging regime is designed to be mechanistic and operates so that all capital spend is logged to the RAB (i.e. “allowable” capital spend) with only a limited category of specific types of cost which are excluded”.[71]

Moreover, in their Guidance document, Ofgem indicate that:

“We expect to ordinarily accept the ITA’s recommendations during the pre-PCR phase. This includes their recommendation on the achievement of the commercial operations date as prescribed in the economic licence, and their recommendations on determining allowable and excluded expenditure during the pre-PCR phase”.[72]

Overall, the formulaic and mechanistic approach to the calculation of the RAB leaves limited scope for regulatory scrutiny and oversight of the construction costs of the project. In the event that the RAB exceeds the LRT, we would expect some provision for review, including greater scrutiny and visibility of the performance of SZC.

Concerns about the governance of the Independent Technical Adviser

The licence modifications also establish a critical role for the ITA.