1. Introduction

The consumer duty aims to put consumer interests at the heart of strategic decision-making across the public sector to deliver better policy outcomes for Scotland.

The consumer duty

The Consumer Scotland Act 2020 (‘the 2020 Act’) introduced a duty (“the consumer duty”) on ‘relevant public authorities’ in Scotland, when making decisions of a strategic nature about how to exercise their functions, to have regard to:

- the impact of those decisions on consumers in Scotland, and

- the desirability of reducing harm to consumers in Scotland

An outcomes based approach should be taken to meet the duty with a focus on providing better quality services and outcomes for consumers, as users of public services.

By taking an outcomes based approach to meeting the duty, Consumer Scotland recommends that public authorities consider how the consumer principles set out in chapter 2 can be applied to strategic decision making to improve outcomes for consumers.

Background

The Consumer Scotland Act 2020 (the 2020 Act) established Consumer Scotland as the independent statutory body for consumer advocacy and advice in Scotland.

Through consultation, stakeholders voiced the need for comprehensive change in how the interests of consumers are considered and integrated into public authority strategic policy and decision making to help achieve positive outcomes for consumers. This led to the introduction of a duty (“the consumer duty”) on ‘relevant public authorities’ in Scotland within the 2020 Act.

Public authorities subject to the duty

A ‘relevant public authority’ is a public authority which is specified in regulations by Scottish Ministers. A full list of authorities subject to the duty from 1 April 2024 can be found in the Scottish Statutory Instrument laid before the Scottish Parliament.

Who is a consumer?

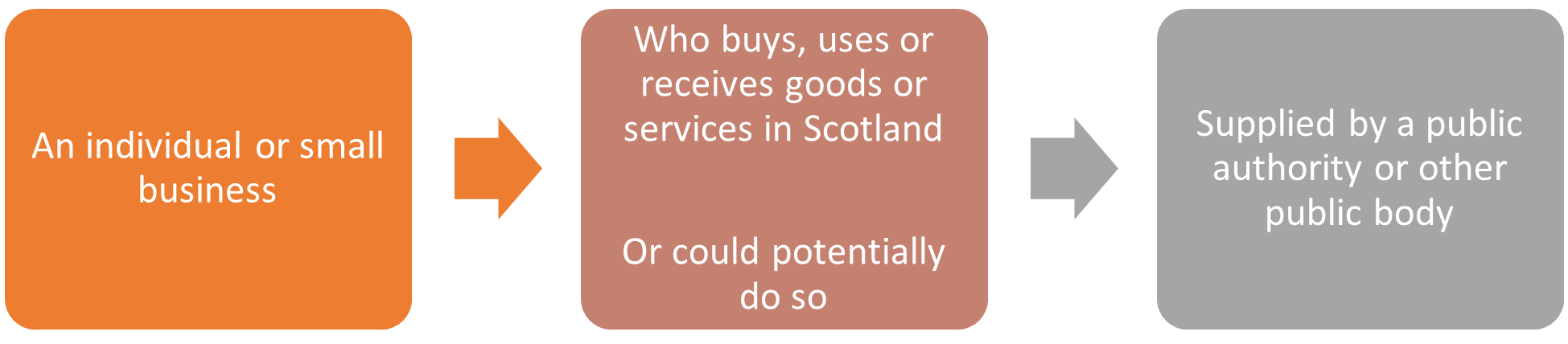

The 2020 Act includes a broad definition of a consumer including individuals, small businesses and future consumers. Crucially for public authorities, the definition of a business is broad enough to cover users of public services:

“business” includes a profession, a not for profit enterprise (within the meaning of section 252(1F) of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997) and the activities of any government department, local or public authority or other public body.[1]

A consumer therefore includes individuals or businesses who meet the following definition:

An individual or small business who buys, uses or receives goods or services in Scotland, or could potentially do so, supplied by a public authority or other public body.

Public service users who may not have been traditionally thought of as ‘consumers’ will therefore meet the definition of a consumer, regardless of whether or not they pay directly for that service. For example, this could include the provision of statutory services by a public authority where no alternative service provider exists, such as waste and recycling services provided by a local authority.

Annex A includes more information on the definition of a consumer.

What is a strategic decision?

It will be for each individual public authority to determine if a decision is of a strategic nature. However, it is expected that this type of decision will be made at an executive or board level rather than operational day-to-day decision making. It is important to note that the duty also applies to any changes to, or reviews of, these decisions. Further information relating to strategic decisions can be found at Annex A.

Requirements on relevant public authorities

The Act sets out four requirements on relevant public authorities:

- When making decisions of a strategic nature, to have regard to the impact those decisions have on consumers

- When making decisions of a strategic nature, to have regard to the desirability of reducing harm to consumers

- Publication of information about the steps taken to meet the duty

- Having regard to this guidance

While this guidance focuses mostly on meeting the first two requirements, chapter 3 and Annex D provide more information on how to meet the publication requirement. ‘Having regard to this guidance’ will also help relevant authorities meet the other three requirements.

Benefits to public authorities

Evidence shows that many people in Scotland are not satisfied with the quality of public services and that the level of satisfaction is reducing. For example, the Scottish Household Survey 2021 found that:

55% of adults were satisfied with all three of the main public services (local health services, schools and public transport). This is a combined measure of the three services and gives an indication on the 'quality of public services'.[2]

The survey also found that combined satisfaction in the three main public services had dropped from 61% the previous year.

At the same time, the public are becoming more aware of the impact they can have on public services and want to be more involved in local decision making: in 2021, 44% of adults wanted to be more involved in the decisions their council make that affect their local area, compared to 39% the previous year.

The duty should be applied in a proportionate and targeted way and not be an onerous task for public authorities.

Meeting the requirements of the duty set out above will not only improve outcomes for consumers, it will also provide value to the relevant public authorities and improve the services they provide. Benefits could include helping them to:

- Make improved strategic decisions and design better policies at every stage of the policy-making process

- Identify potential consumer detriment, understanding consumers’ behaviour and perspectives, and ensuring that policies and strategic decisions are designed around these points

- Work in partnership with consumers to achieve better outcomes for both consumers and public authorities

- Ensure better value for money and support them in producing evidence to demonstrate better value for money

- Make it easier for the public (consumers and service users) to relate to policies made in this way

- Over time, inspire greater levels of trust and confidence in public authorities

- Experience lower levels of consumer dissatisfaction and complaints about the services public authorities provide

2. Purpose of this guidance

This draft guidance document has been produced by Consumer Scotland in accordance with the powers provided by the 2020 Act.[3]

It has been developed to assist the relevant public authorities in meeting the requirements of the consumer duty per the 2020 Act. The guidance should help public authorities embed the consumer perspective into strategic decision making, provide better outcomes for consumers and consider how consumer harm can be reduced.

The 2020 Act states that public authorities must have regard to the guidance, including this draft version. The draft guidance has been published alongside a public consultation, findings from which will inform a final version. Following the consultation, an overview of our findings and conclusions will be published here within the final draft.

The guidance is made up of two key sections:

- Advice on the approach relevant public authorities should take to meeting the duty

- Advice on how to ensure the duty has been met

There is also a suite of annexes and resources included to assist public authorities in meeting the duty.

Dependent on their needs, users of this guidance might want to focus their attention on specific sections:

- Those looking for a brief introduction to the duty and explanation of what it is might want to refer to chapter 1

- Senior decision makers[4] of an equivalent governance body might be most interested in chapter 3 – meeting the duty, which includes a “Senior Decision Makers and the Duty” section. There is also a separate short guidance document aimed specifically at senior decision makers within relevant authorities[5] on the Consumer Scotland website

- While the overall guidance document is aimed at officials of relevant public authorities, chapters 2 and 3 might be of most use to these users given the focus on approaching and meeting the duty

A recommended approach to meeting the duty, along with real life examples, is provided throughout this document. However, authorities are encouraged to take a flexible, proportionate and targeted approach to meeting the duty that reflects their own organisational circumstances and priorities.

Developing the guidance

This document has been developed with input from an advisory group with representation from the Scottish Government, public authorities, and other key stakeholders.

The advisory group has supported the development of the guidance while providing advice and expertise on how to ensure the guidance meets the needs of public authorities and helps to ensure that the duty improves outcomes for consumers. The membership of the group included representatives from:

- Scottish Public Service Ombudsman

- Improvement Service

- COSLA

- Scottish Government

- Home Energy Scotland

- Food Standards Scotland

- Transport Scotland

- Scottish Rail Holdings

- Carolyn Hirst (consultant)

Update here on work to finalise the guidance when available.

3. Approach to the consumer duty

This section introduces the outcomes-based approach to the consumer duty that we recommend public authorities should take to deliver improved polices and achieve the best outcomes for users of their services and consumers more generally.

Aims of the duty

The duty puts improving outcomes for consumers at the forefront of public authorities’ decision making given the importance consumers in Scotland attach to the accessibility and affordability of public services.

In its response to the Christie Commission report on the future of delivery of public services, the Scottish Government stated:

“The people of Scotland attach the highest value to their public services. The quality of those services is part of the bedrock on which our society and future prosperity depends, and is crucial in shaping a flourishing, productive and equitable Scotland.”[6]

At a time of greater demand for public services and when public finances are under increasing pressure, it is more important than ever that public services are focused on the needs of their users and their local communities.

Recent research found that just under half (48%) of respondents said that healthcare and the NHS was one of the top three issues facing Scotland.[7] This was slightly ahead of the cost of living crisis and concern for social care and housing issues. Spending on public services was also seen as being among the top three issues facing the economy by one-quarter of respondents.

In its consultation paper on the consumer duty[8], the Scottish Government set out the main aims of the duty as follows:

- To embed the consumer perspective into strategic decision-making processes across the public sector, to deliver better policy outcomes for Scotland.

- To challenge relevant public authorities to be more robust and methodical in their evaluation of the impact of strategic decisions on consumer groups.

- To steer relevant public authorities towards a solution orientated approach to managing the risk of consumer detriment where identified.

- To encourage relevant public authorities to be proactive in their engagement and consideration of consumer behaviour as a driver to achieve policy objectives.

More information on how to meet these aims can be found in chapter 3.

Principles of better regulation

The Scottish Government intends that the duty should be applied in a proportionate and targeted way, in line with the better regulation principles. It recognises that “the consumer duty must be carefully developed so that it has a meaningful impact without becoming a burden on public authorities”.[9]

Public authorities should however take care to not treat the requirements of the duty as a tick box exercise. The focus should be on demonstrating where positive outcomes have been achieved for, and reducing harm to, consumers.

Consumer principles and outcomes-based approach

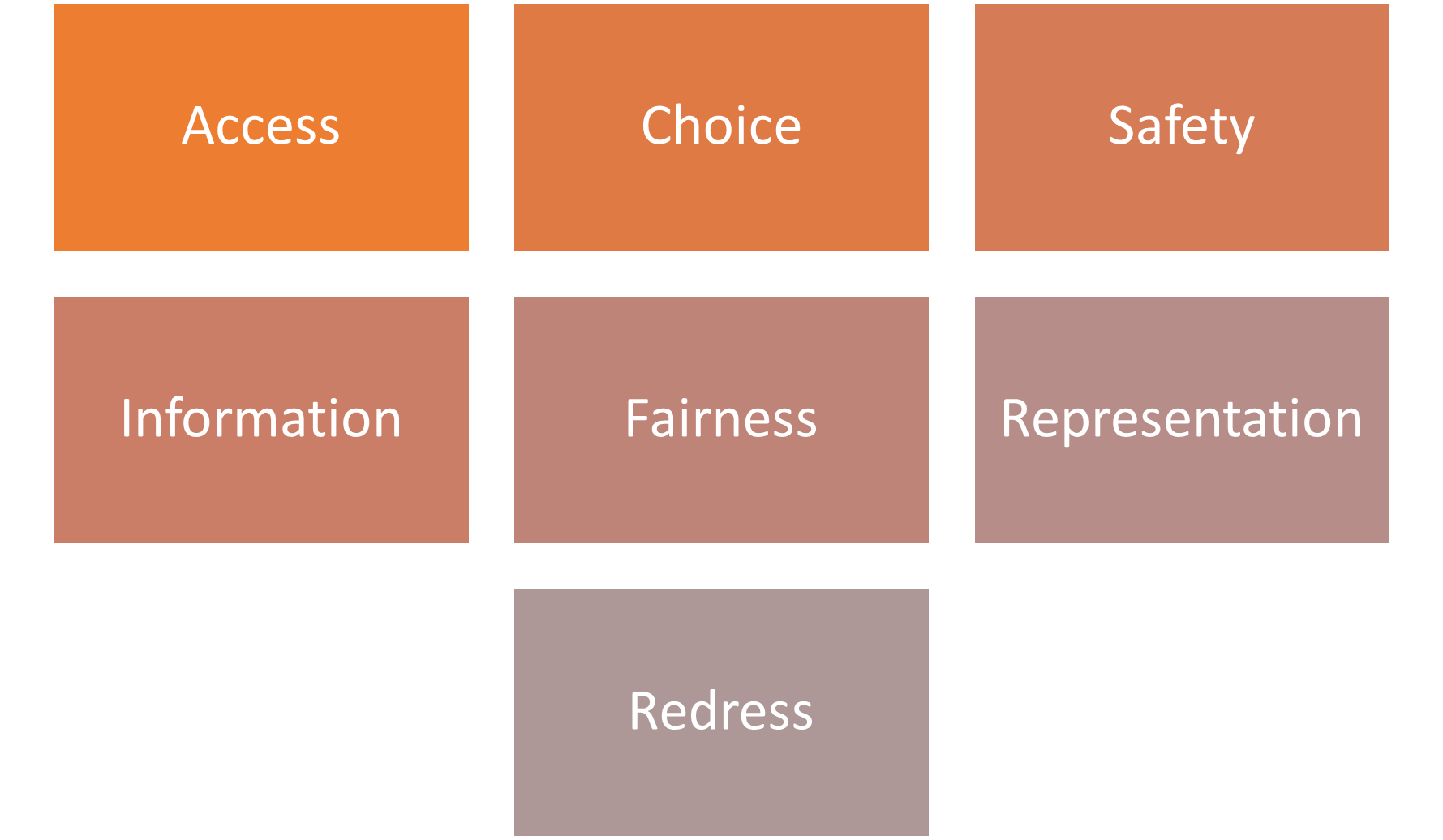

Consumer Scotland has adopted a set of consumer principles, drawing on the internationally recognised principles adopted by the UN General Assembly.[10] These principles underpin our policy analysis and development and help assess the consumer interest. Public authorities should consider these principles and how they can be used when making strategic decisions.

The consumer principles provide a framework to understand consumer needs and outcomes and how to minimise harm and maximise value and benefits to consumers. Considering the seven principles below should help public authorities meet their consumer duty requirements to have regard to the impact on consumers and to the desirability of reducing harm to consumers when making strategic decisions.

It is suggested that the principles should be considered throughout all stages of the impact assessment process. Questions should be asked throughout the process to ensure relevant consumer principles are met. Example questions have been provided for officials to ensure their strategic decision making meets the principles in Annex B.

The seven consumer principles are access, choice, safety, information, fairness, representation and redress.

Outcomes from applying the consumer principles will vary for each organisation but some examples are included below with example questions officials can ask to help meet these principles included at Annex B.

Example outcomes from applying the consumer principles

Access – can people get the goods or services they need or want?

- Access to goods and services is available in a way that makes them easy and simple to use and encourages take up

- Legislation and regulation support ease of access to goods and services

- Access to essential services is adequately protected and mitigation measures are available to ensure continued services where there are known problems

Choice - is there any meaningful choice? While there might not be choice of service provider or what service is provided, choice might sometimes mean how a service is provided.

- Consumers can choose from a range of goods and services that best meets their needs and wants

- Choice is authentic with the intention of providing consumers with transparent offerings

Safety - are consumers adequately protected from risks of harm?

- Adequate measures are in place to protect consumers from harm

- Where there is evidence of harm to consumers, action is being taken to adequately address issues and eliminate them

Information - is it accessible, accurate and useful?

- Available information provides consumers with what they need to know to allow them to make good choices or to undertake action

- Information is easy to find and presented in a way that is easily understood

Fairness - are all consumers treated fairly?

- Goods and services are inclusive

- Goods and services are delivered or sold in a fair way that does not discriminate between individuals or groups of consumers [11,12]

Representation - do consumers have a meaningful role in shaping how goods and services are designed and provided?

- Consumers views, needs and experiences are informing the design and delivery of current and future goods and services

- Public authorities can demonstrate where consumers have influenced outcomes

Redress - if things go wrong, is there an accessible and straightforward way to put them right?

- Consumers are clearly signposted to redress support services and procedures

- Redress procedures are clear and simple to engage with.

- There is a clear commitment to resolve consumer issues where a complaint has been raised or where a customer has raised an informal concern

Financial Conduct Authority consumer duty example

An example of an outcomes-based approach to a consumer duty can be seen in the consumer duty introduced for financial services firms by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in July 2023. The consumer duty has been implemented as one of the FCA’s overarching principles, ‘the fundamental obligations of firms and the other persons to whom they apply under the regulatory system’ with the express goal of delivering good outcomes for retail customers.

The FCA consumer duty is not a prescriptive set of processes firms must follow. Instead, the duty focuses on achieving positive outcomes for consumers in four areas: products and services, price and value, consumer understanding and consumer support. Firms are encouraged to adopt a suitable approach that achieves these goals.

It is recommended that public authorities subject to the consumer duty should adopt a similar outcomes-based approach to meeting the duty.

Financial Conduct Authority consumer duty example

A firm must act to deliver good outcomes for consumers.” (Principle 2)

Rules:

Firms must act in good faith towards retail customers.

Firms must avoid causing foreseeable harm to retail customers.

Firms must enable and support retail customers to pursue their financial objectives

Outcomes:

Products and services - these must be fit for purpose and designed to meet the needs, characteristics, and objectives of consumers in the identified market

Price and value - firms must consider whether products and services represent fair value

Consumer understanding - communication to customers must be such that they are able to make informed decisions

Consumer support - firms are expected to provide support that meets the needs of customers

Impact Assessment Approach

Public authorities are advised to adopt a flexible, proportionate and targeted approach to meeting the duty and we recommend that public authorities adopt the impact assessment approach set out below. This approach is intended to provide a consistent method to meeting the duty and the requirement on public authorities to report on how they have done so.

There are a number of existing impact assessments that public authorities are subject to in Scotland and more information on these can be found on the Scottish Government website. By adopting a proportionate approach to meeting the consumer duty, consideration should be given to how to adopt an integrated approach to meeting the requirements of the applicable impact assessments.

Some public authorities already have their own guidance on integrated impact assessments[13] and it may be appropriate to incorporate the consumer duty into that process. The Improvement Service has also produced a Policy Development Framework[14] which provides guidance and sets out a suggested integrated impact assessment approach for local authorities. This aims to ensure that:

- they take a clear and consistent approach to the development, implementation, and management of policy, and

- those developing policies are clear as to what they must take into consideration when developing or reviewing a policy.

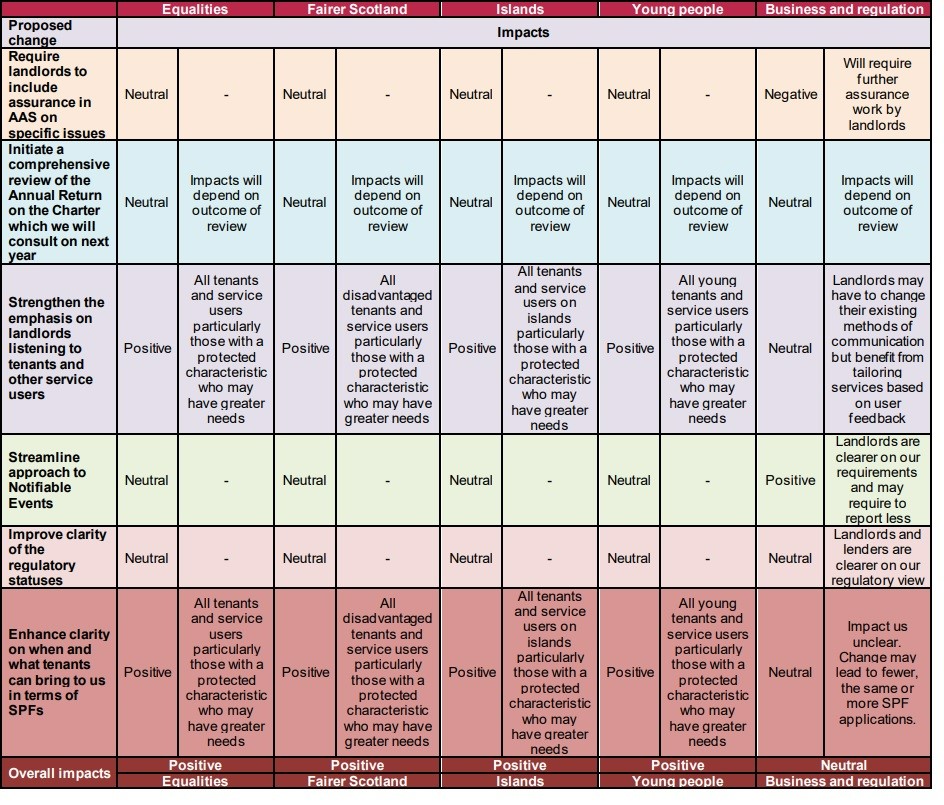

The chart below is an example of an integrated impact assessment approach taken by the Scottish Housing Regulator for its consultation on the future regulation of social housing in Scotland which included proposed changes to its regulatory framework and statutory guidance.[15]

As part of this process, they conducted a combined impact assessment that presents findings relevant to the Equalities Impact Assessment, Fairer Scotland Duty Assessment, Island Communities Impact Assessment, Children’s Rights and Wellbeing Impact Assessment and the Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment. The findings are presented below as an example of how an integrated approach to impact assessments can be taken and presented.

The most appropriate approach however to meeting the duty will be for individual public authorities to decide, while also ensuring that the legal requirements of the duty are still met.

Further information on taking an impact assessment approach can be found in the next chapter: Meeting the duty.

Scottish Housing Regulator integrated impact assessment approach example

4. Meeting the Duty

It is recommended that public authorities adopt an outcomes-based approach to meeting the duty. They should engage with consumers throughout the process and apply the consumer principles to strategic decision making to improve outcomes and consider how to reduce harm to consumers.

This section sets out an example process of how public authorities can meet the duty. The impact assessment approach has been developed to provide a comprehensive approach to achieving the goals of the duty which is consistent with meeting other statutory requirements such as the Equality Impact Assessment (EQUIA) and the Fairer Scotland Duty.

As stated in chapter 2, the 2020 Act placed four requirements on public authorities subject to the duty. The consumer principles set out above should be kept in mind when meeting these requirements:

- When making decisions of a strategic nature, have regard to the impact those decisions have on consumers

- When making decisions of a strategic nature, have regard to the desirability of reducing harm to consumers

- Publication of information about the steps taken to meet the duty

- Have regard to this guidance

Public authorities subject to the duty will perform a wide variety of functions and the frequency in taking strategic decisions will vary for each authority. This means that there may be times when an alternative approach to the impact assessment approach set out in this guidance might work better for some public authorities.

It is also worth noting that the functions of public authorities can change over time – for example, when given new responsibilities by government. Any change to the functions of a public body should be reflected in its engagement with the duty but remain a proportionate, targeted and flexible approach that focuses on achieving the best outcomes for consumers.

Preparing to meet the duty

Public authorities should take sufficient steps to prepare for the duty. This could include measures such as:

- Ensuring leadership are on-board with the objectives of the duty

- Awareness raising throughout the organisation

- Engaging with consumers

What if you’re already meeting the duty?

You may feel that your organisation is already meeting the requirements of the consumer duty for some strategic decisions, and that you are already giving sufficient regard to the impact those decisions have on consumers and to the desirability of reducing harm to them. In this circumstance, undertaking the full impact assessment process might not be necessary and it may be sufficient to ensure a record is kept of how you have met the duty for this strategic decision.

Regardless of how you have met the consumer duty, the two remaining requirements of the 2020 Act still apply:

- Publication of information about the steps taken to meet the duty

- Having regard to this guidance

When deciding whether or not to complete the full impact assessment, consideration should be given to whether you have met the aim of the duty by putting consumers at the centre of your decision making and improving outcomes for them.

Senior decision makers’ engagement with the duty

Responsibility for meeting the duty should lie with an organisation’s board or equivalent group of senior decision makers and these decision makers should also play a role in scrutinising efforts to meet the duty. There is a separate guidance document for ‘senior decision makers[16] of relevant public authorities, which focuses on the specific responsibilities of senior leaders to meet the duty.

Who constitutes a senior decision maker will vary across the public sector. This role will often be undertaken by board members at public authorities but also includes elected officials within local authorities. Senior leaders looking for further information on how to perform their role in meeting the duty should refer to the guidance for senior decision makers.

Scrutiny is “the process of holding ‘others’ to account through monitoring, examination and questioning of decisions, actions and performance”[17] to achieve improvement. The example questions below have been broken down according to the five stages of the impact assessment process to help identify relevant questions that will support the improvement of outcomes for consumers.

A list of example scrutiny questions

Planning stage questions:

- Do you consider this to be a 'strategic decision' in line with the consumer duty guidance? (if not, why not?)

- Is this decision likely to have an impact on any/all consumers?

- Have you considered/reviewed the consumer duty guidance before planning this proposal?

- Has an outcomes-based approach been taken to planning this project?

- Have you considered how this proposal meets the consumer duty requirements?

- How do you plan to meet the consumer duty with respect to this project/proposal/plan?

- What plans are in place to ensure that the three requirements of the consumer duty are met?

- What consumer engagement plans have been made?

- What plans do you have for ensuring appropriate consumer engagement is undertaken throughout the entire process?

- What approach are you taking to ensure we meet the requirements of the consumer duty? E.g., impact assessment?

Evidence gathering stage questions:

- Has sufficient evidence been gathered to evaluate the outcomes of this project and meet the consumer duty?

- What consumer engagement has been undertaken?

- Have any evidence gaps been identified? Could these be filled with further consumer engagement?

Assessment and improvement of proposal questions:

- Have you assessed the impact of the proposal on consumers?

- Have you identified alternative options that would improve outcomes for consumers?

Decision stage questions:

- How does the final decision impact on consumers?

- Why were alternative options not chosen and what would have been the outcomes for consumers in these scenarios?

- Was the best option for consumers chosen? If not, why not?

Publication stage questions:

- How will you publish the steps taken to meet the duty?

Evaluation of the approach taken to meet the duty:

- Did you meet the four statutory duty requirements of the consumer duty?

- Did your approach to meeting the duty help improve outcomes for consumers? If not, how could this be improved in the future?

- Is there anything that could be changed to improve the approach to meeting the duty in future?

Consumer duty champion

Authorities are also encouraged to adopt awareness raising measures to ensure leadership are on board with the approach to meeting the duty and appoint a “champion” at board or equivalent level. The champion should then work to ensure the duty is being considered as part of the strategic decision-making process and that it is embedded within the authority’s decision-making culture and not treated a tick-box exercise. Further guidance for senior decision makers on how to challenge whether their organisation is meeting the duty is provided in a separate guidance document.[18]

Training may be required to ensure that senior management at an operational level, including the Accountable Officer understand the purpose of the duty and their responsibilities under the 2020 Act.

Engaging with consumers

Most public authorities should already be aware of the importance of engaging consumers in their decision-making as the Scottish Government already expects public service providers to “work with… communities to deliver services which recognise the importance of people, prevention, performance and partnership”.[19]

There are however practical guides to assist with selecting the correct level of participation. IAP2's Spectrum of Public Participation[20] was designed to assist with the selection of the level of participation that defines the public's role in any public participation process.

The consumer principles, as discussed above, can be used as an effective framework for consumer engagement to achieve improved outcomes for consumers.

Consumer engagement can be undertaken throughout the impact assessment process. It can help a public authority to understand the aims and outcomes of a proposal (planning), it is a method of data gathering (gathering evidence), it can be used to assess the impact of a proposal on consumers (assessment and improvement of proposals), and it can be used to agree changes to a proposal (decision).

A practical example of effective consumer engagement from Scottish Water:

Scottish Water Strategic Plan

Scottish Water is publicly owned, commercially managed and ultimately answerable to the people of Scotland through Scottish Ministers and the Scottish Parliament for the services it delivers.

They provide services to all consumers in Scotland and understanding the views and needs of consumers is therefore an important part of their long term planning process. An extensive consumer engagement programme[21] was therefore undertaken as part of the process to develop their Strategic Plan.[22]

Setting up a Customer Forum was a key part of this process. The forum then worked in partnership with Scottish Water to commission in depth research on how to provide the best service to consumers and ensure Scottish Water meets the needs of both current and future customers.

This research sought the views of thousands of consumers across Scotland through a range of different projects. Importantly, the findings from the consumer engagement have been given prominence in the Scottish Water Strategic plan, with achieving positive consumer outcomes outlined as the key goal upfront in the Plan:

‘This plan is focused on how we will meet our customers’ current and future expectations’

Consumer engagement did not end with the publication of the Strategic Plan and the Independent Customer Group[23] was established to help ensure the objectives set out in the Plan are achieved.

Consumers in vulnerable circumstances

Although the consumer duty applies to all consumers, public authorities are encouraged to consider the impact of strategic decisions on consumers in vulnerable circumstances, and the desirability of avoiding harm to these groups of consumers where appropriate.

This work should be undertaken with due regard to existing public sector equality duty[24], and Scottish specific duties[25], requirements.

Engagement with consumers in vulnerable circumstances about the impact strategic decisions can have on them is strongly encouraged. This work should be prioritised but should also be proportionate and targeted. Some strategic decisions are more likely to impact vulnerable consumers or, have a more significant impact on them than others.

Further information on what is meant by ‘consumers in vulnerable circumstances’ can be found in the Annex A.

An example of engaging with consumers in vulnerable circumstances can be seen in the work by Fair By Design on ‘inclusive design’. Inclusive design is the practice of designing products and services so that everyone can use them and it aims to include people with lived experience of an issue in the design process.[26]

An example of engaging with consumer in vulnerable circumstances is outlined in the fair transition to net zero for low-income consumers report by Toynbee Hall in partnership with Fair by Design and Ofgem[27]

The Toynbee Hall report on a fair transition to net zero for low-income consumers used a Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach to explore what a fair transition to net zero for low-income consumers could look like. PAR involves professional researchers and people with lived experience of an issue (peer researchers) working as equal partners. PAR is founded on the premise that systems, services, and policies are more effective when designed with those with direct experience of the problem to be solved.

The report, stating that inclusive design means “essential services should be designed so all consumers are able to access and use the products and services they need, at a fair price”, found that “The findings from the PAR show how important it is to have inclusive design at the forefront of policy. Including people with lived experience of an issue within policy creation and decision-making is the best way to deliver a market that works for all consumers.”

The Impact Assessment

The impact assessment process includes five stages:

- Planning

- Gathering Evidence

- Assessment and improvement of proposal

- Decision

- Publication

Considering how to meet the duty should begin at the start of the decision-making process. This means the planning stage and appropriate consumer engagement should be undertaken per the Scottish Government’s aims for the duty:

“To encourage relevant public authorities to be proactive in their engagement and consideration of consumer behaviour as a driver to achieve policy objectives”

Performing the impact assessment

This section sets out an example process of how public authorities can meet the duty and a recommended impact assessment template with completed examples is included at Annex F. These have been developed to provide a comprehensive approach to achieving the goals of the duty which is consistent with meeting other statutory requirements.

In 2021, the Scottish Government conducted a literature review of impact assessment in governments[28] which identified preconditions that should be present for conducting an effective impact assessment. These conditions included:

- High-level commitment and supportive organisations

- Policymakers’ willingness to learn and change in response to the assessment findings

- Oversight and quality review of the assessments

- Fitting the assessment to the decision in terms of timing, types of alternatives considered, recommendations etc.

- Involvement of the public/stakeholders

- Starting the impact assessment early in the policy-making process

- Adequate funding

- Adequate data and expertise

- Collaboration and information sharing between assessors and government departments

- Follow up to check whether the policy incorporated the assessment recommendations, whether the assessment adequately identified impacts, and how the assessment process can be improved

Ensuring these conditions exist when completing your impact assessment will increase the chances of the impact assessment process being as effective as possible.

The impact assessment has five stages which are discussed below and a tool to evaluate your approach is included in Annex G.

Five Stages of the Impact Assessment

Stage 1 - Planning

Public authorities should first decide whether the duty applies and, if the conclusion is that it does then they should begin at the planning stage.

Key tasks at this stage:

- Decide if this is a strategic decision or not. If not, then no action is required

- Decide if the strategic decision is likely to have an impact on any or all consumers. If not, then proceed to stage 5.

- Decide if you have already met the consumer duty for this strategic decision, if you have then proceed to stage 5.

- If this is a strategic decision, and this will have an impact on consumers, then develop a plan for how to complete stages 2-5, including required consumer engagement.

- Understand the aims and outcomes of the proposal and identify alternative options.

Achieving the best outcome for consumers and reducing harm to them should form an integral part of the whole strategic decision-making process. How to meet the duty should be considered from the planning stage of a proposal, it should not be treated as a tick box exercise at the end of the process.

The key questions at the planning stage are whether the proposal is a strategic decision and if it will have an impact on consumers (including small businesses) as defined by the 2020 Act. If it is not a strategic decision, or it will not have an impact on consumers, then there is no requirement to meet the duty.

However, public authorities are still encouraged to consider how to achieve the best outcome for consumers when making any decisions, for all the reasons set out in this guidance.

If there is no strategic decision then you can proceed to stage 5: publication. Annex E provides a pro forma ‘assessment not required’ template to record the decision that the consumer duty does not apply. Recording these decisions will help with stage 5 of the process (publication) and demonstrate how you have taken steps to meet the duty.

If there is a strategic decision, then authorities should develop a plan for completing stages 2-5, including identifying what consumer engagement is required. Part of this process will involve understanding the aims and outcomes of the proposal and identifying alternative options.

Officials should refer to the consumer principles when designing aims and outcomes for a proposal to maximise the positive impact on consumers. Taking this approach will help public authorities develop policies that better meet consumers’ needs, inspire greater trust and confidence in public authorities and lower levels of consumer dissatisfaction and complaints.

Stage 2 – Evidence gathering

Following the planning stage, authorities should undertake evidence gathering. This stage is used to gather data that will help a public body to demonstrate that they have met the requirements of the duty.

Following the planning stage authorities should undertake evidence gathering. This stage is used to gather data that will help a public body meet the requirements of the duty.

Authorities should make full use of the data already available to them where possible before to minimise workload. Any evidence that needs to be gathered should, at a minimum, answer the questions below:

- What is the proposal trying to achieve?

- What are the impacts on consumers?

- Is it likely that harm will be experienced by consumers as a result of this proposal?

- What alternative proposals are there that can improve outcomes for consumers and/or reduce harm to consumers?

- How do these alternative proposals compare to the original proposal?

If there is a gap in the required evidence, consideration should be given to the appropriate level of consumer engagement needed to obtain this evidence.

Stage 3 - Assessment and improvement of proposal

At this stage, officials will use the evidence gathered to answer the questions above to show that the public body has met the duty and had regard to:

- The impact of a strategic decision on consumers in Scotland

- The desirability of reducing harm to consumers in Scotland

The answers to the questions set out at stage 2 should be used to assess the impact of the strategic decision on consumers and consideration given to improving the proposal to achieve a better outcome for consumers.

Whether there is a need for any additional consumer engagement should also be considered at this stage, especially if significant changes have been made to original proposals.

Stage 4 - Decision

The decision stage should be used to consider the results of the previous stages, agree any changes to the proposal and set out clearly how the public authority has met the consumer duty for this particular strategic decision.

It may be necessary to weigh up competing interests and potential harm to different groups of consumers. Consideration of the impact on consumers in vulnerable circumstances may also carry significant weight. In these circumstances, the impact on the majority of consumers may be a persuasive factor in the decision making but the final decision is for individual public authorities to make, and to demonstrate why they have done so.

Meeting the duty should mean that:

- The impact of the strategic decision on consumers and the desirability of reducing harm to consumers have been considered throughout the process

- That an outcomes-based approach has been taken to achieve the best outcomes for consumers

Documenting how the authority has met the duty will help with completing stage 5 – Publication.

Stage 5 - Publication

Section 23 of the 2020 Act requires public authorities to publish information about the steps which they have taken to meet the duty.[29]

The authority must publish the information no later than 12 months after the end of period to which it relates.

Documentation from the decision-making stage will help authorities to meet this requirement.

It is up to individual authorities to decide on the most appropriate way to meet this requirement. This guidance does provide some examples, but possible approaches could include:

- A statement in an annual report

- Publishing the consumer duty impact assessment alongside the relevant proposal

A suggested pro forma template for an annual report statement can be accessed in Annex D.

Once the impact assessment process has been completed, public authorities are encouraged to review how effective their approach to meeting the duty was. This will help them to reflect on what went well and what might be improved in the future. It will also help you to monitor whether you are meeting the duty effectively and will assist you in reporting on this. An evaluation tool to help you do this is included in Annex G.

5. Annex A: Definitions

The Consumer Scotland Act 2020 (Relevant Public Authorities) Regulations 2024[30] (the 2024 Regulations) brought the duty into force. This annex clearly explains some of the terms used in the Consumer Scotland Act 2020 and the regulations, including:

- Relevant public authority

- Consumer

- Impact on consumers

- Harm to consumers

- Decisions of a strategic nature

- Have regard to

- Goods and services

The detailed explanations of how to interpret terms related to the duty included in this section may be helpful to officers within public authorities who are responsible for ensuring that their organisation meets the duty.

Relevant public authority

The 2020 Act defines a relevant public authority as: “a person with functions of a public nature who is specified (by name or description) in regulations made by the Scottish Ministers”.[31] A full list of relevant public authorities can be found in the 2024 Regulations.

Consumer

The definition of ‘consumer’ is taken from the 2020 Act[32] and includes both individuals and small businesses, as explained below:

Individual consumers

A ‘consumer’ is an individual:

- who purchases, uses, or receives, in Scotland, goods or services which are supplied in the course of a business carried on by the person supplying them, and

- who is not purchasing, using, or receiving the goods or services wholly or mainly in the course of a business carried on by the individual.

A consumer includes both an existing consumer and a potential consumer (including a future consumer).

Small business consumers

A ‘consumer’ includes a business

- which is no larger than a small business[33]

- a small business is a business with less than 50 employees and a turnover a turnover or balance sheet total less than or equal to the small business threshold.”

- which purchases, uses, or receives, in Scotland, goods or services which are supplied in the course of a business carried on by the person supplying them.

A ‘business’ (as in “in the course of a business”) is defined in the 2020 Act as including the activities of any government department, local or public authority or other public body. This means that users of the services provided by public authorities are included within the definition of consumers.

“Consumers” can therefore be summarised as:

- Individuals who buy, use, or receive goods or services (or who could potentially do so) in Scotland supplied by a business.

- Individuals who buy, use, or receive goods or services (or who could potentially do so) in Scotland which are provided by a public body.

- Small businesses who buy, use, or receive goods or services (or who could potentially do so) in Scotland supplied by a business.

- Small businesses who buy, use, or receive goods or services (or who could potentially do so) in Scotland which are provided by a public body.

The definition of "consumers" therefore is a very broad, in effect, everyone in Scotland is a consumer.

Public authorities should take care to ensure they understand that users of public services are considered to be consumers for the purposes of the consumer duty. This includes using statutory services such as waste and recycling, education, and health and social care services etc. provided by public authorities.

Example consumers:

|

Example service |

Example service provider |

Example consumers |

|

Waste and recycling services |

Local authority |

Local residents and small businesses making use of the services |

|

Education services provided by state school |

Local authority |

Pupils receiving education services Parents of pupils |

|

Healthcare at a hospital |

Local health board |

Patients |

|

Student loan repayment services e.g. online account, payment options, advice etc. |

Student Awards Agency Scotland |

Student loan recipients |

|

Businesses looking for advice on how to move to Net Zero |

Zero Waste Scotland |

Small businesses looking for advice on moving to less environmentally damaging practices e.g. reusable cups rather than single-use |

|

Users of water supply services |

Scottish Water |

Home users or small businesses |

|

Business looking for advice on food hygiene standards |

Food Standards Scotland |

Small business |

Harm to consumers

When making strategic decisions, public authorities must have regard to the desirability of reducing harm to consumers. Meeting the consumer duty will involve embedding the consideration of consumer outcomes in strategic decision making and this should involve identifying where harm can be reduced.

This does not mean that reducing harm to consumers must be an objective of policy decisions but the potential for reducing harm to consumers should be considered. As with all elements of the consumer duty, public authorities should take a proportionate and flexible approach to this requirement.

“Harm” to consumers can be interpreted in a wide variety of ways and public authorities are therefore encouraged to adopt a broad definition that encompasses a wide range of potential negative outcomes for consumers. Harm can:

- encompass situations that cause consumers stress

- cost them money or

- take up their time

Harm can include incidents that consumers consider worthy of complaint, it could be hidden to the consumer or be structural such as access to justice issues. For example, some consumers are unaware of the services they are entitled to due to lack of awareness, resilience, or knowledge of how to access them.

Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) market studies have identified specific examples of consumer harm. This includes some consumers being unable to access market benefits such as more affordable energy tariffs or ability to switch providers as easily as others and costing them more to heat their homes.

There are also issues that affect Scotland more than the rest of the UK. For example, consumers living in more remote areas of Scotland can incur much higher costs for parcel deliveries or find that some couriers will not deliver to their address[34]

Public authorities will understand their own operations best and the potential for reducing harm to consumers.

They should take the time to identify where they could reduce harm to consumers as part of the impact assessment approach described in this guidance. They should also take care to note the broad definition of consumers above, including individuals, small businesses, users of public services and potential consumers.

Decisions of a strategic nature

The duty applies to strategic decisions. While it is for public authorities themselves to determine whether a decision is strategic or not, strategic decisions tend to be key, high-level decisions taken by senior decision makers that fulfils the body’s intended purpose over a significant period.

This could include deciding priorities and setting objectives but can also be made over the short or medium-term, particularly when responding to urgent emerging circumstances.

Such decisions may also be coordinated with other strategic decisions as part of an overarching plan. These would normally include strategy documents, decisions about setting priorities, allocating resources, delivery or implementation and commissioning services. The duty also applies to any changes to, or reviews of, these decisions, not just the development of new strategic documents.

Strategic decisions will have a major impact on the way in which other tactical and day-to-day operational decisions are taken. Some public authorities may only take strategic decisions occasionally such as once a year however, others may do so more frequently.

While this guidance does not include an extensive list of decisions that are strategic in nature, some examples are included below but each organisation subject to the duty must identify for itself the strategic decisions it makes.

Examples of a strategic decision could include (but are not exclusive to):

- Implementing legislation

- Preparation of a corporate or strategic plan

- Agreeing an annual budget

- Major procurement exercises

- Developing strategies such as a housing strategy, a strategic framework or an education strategy

- Investment/disinvestment decisions

- Major projects such as restructuring, significant strategy decisions or other change management decisions

This guidance document is a draft version that will be used to inform a public consultation throughout the one-year implementation period for the consumer duty. It is Consumer Scotland’s intention to work with the relevant authorities who use this guidance to provide some worked specific examples of strategic decisions to be included in the final draft.

Have regard

A proportionate approach to meeting the duty should be adopted. This means public authorities are required to ‘have regard to’ the two elements of the duty when making strategic decisions. They do not have to go beyond that or give them overriding weight during the decision-making process, as long as they can demonstrate that they have done this.

Consumers in vulnerable circumstances

Although the consumer duty applies to all consumers (as defined above), public authorities are particularly encouraged to consider the impact of strategic decisions on vulnerable consumers and the desirability of avoiding harm to such consumers where appropriate.

The European Commission has identified five dimensions of consumer vulnerability. It defined a vulnerable consumer as: A consumer, who, as a result of socio-demographic characteristics, behavioural characteristics, personal situation, or market environment[35]:

- Is at higher risk of experiencing negative outcomes in the market

- Has limited ability to maximise their well-being

- Has difficulty in obtaining or assimilating information

- Is less able to buy, choose or access suitable products

- Is more susceptible to certain marketing practices.

"Vulnerable consumers” are defined in section 25 of the 2020 Act as consumers who, by reason of their circumstances or characteristics:

- May have significantly fewer or less favourable options as consumers than a typical consumer, or

- Are otherwise at a significantly greater risk of: (i) harm being caused to their interests as consumers, or (ii) harm caused to those interests being more substantial, than would be the case for a typical consumer.Vulnerability is not a static condition. Consumer Scotland and other organisations generally refer to ‘consumers in vulnerable circumstances rather than ‘vulnerable consumers’ for this reason. Consumers may move in and out of states of vulnerability and they may be vulnerable in some contexts but not others.

However, it can also be important to recognise that various personal characteristics, such as a long-standing disability, can imply that vulnerability remains an enduring characteristic for particular groups of consumers.

Certain circumstances may also make some consumers more vulnerable than others. For example, consumers in a difficult financial situation are generally more likely to be vulnerable in some indicators compared to other consumers.

Goods and services

Goods

'Goods’ are not defined in the 2020 Act. They are defined in the Consumer Rights Act 2015 as “any tangible moveable items, but that includes water, gas and electricity if and only if they are put up for supply in a limited volume or set quantity.[36]

Services

‘Services’ are not defined in the 2020 Act or the Consumer Rights Act 2015. However, the consumer duty does apply in relation to consumers of services provided by public authorities covered by the duty. Per above, the definition of ‘business’ includes “the activities of any government, local or public authority or other public body.”

6. Annex B: Consumer Principles

The examples present the consumer principles and outcomes authorities can achieve by applying them to strategic decision making. This annex provides example questions which might be useful for officials when considering how to apply those principles.

Access - Can people get the goods or services they need or want?

Outcomes from applying the principle:

- Evidence that easy and simple access to goods, information or services has been adequately considered

- Evidence that access has been assessed by service users

- Access to goods and services is available in a way that is helpful and engaging

- Legislation and regulation support access to goods and services

- Access to essential services is adequately protected and mitigation measures are available to ensure continued services where there are known problems

Example Questions:

- Is ease of access sufficiently evidenced? Are assumptions being made that suggest that consumers can access offerings but no tangible evidence that this is the case?

- Has access improved as a result or affirmed that it is sufficient and effective?

- Are there barriers that make it difficult for service providers to improve offerings / approach? What are these and what causes them?

- Is there evidence of chronic disruption to essential services that is impacting consumers where contingency is inadequate?

Choice - Is there any meaningful choice?

Outcomes from applying the principle:

- Consumers can choose from a range of goods and services that best meets their needs and wants

- Choice is authentic with the intention of providing consumers with transparent offerings

Example Questions:

- Is there evidence that choice is being used to draw consumers to expensive or unhelpful purchases?

- Choice evidences a range of offerings for consumers, for example, least to most expensive or range of quality or opportunity to minimise inconvenience due to necessary works.

- Information around different options is clear and helpful. Do consumers clearly understand what they will get if they choose a particular option?

If choice is not always available or preferable, such as with a monopoly supplier or a public body’s services, then:

- Policies and practice around essential service provision, where there is no choice, can meet everybody’s needs.

- What more could a public service body do to ensure services meet peoples’ needs?

Safety - Are consumers adequately protected from risks of harm?

Outcomes from applying the principle:

- There is sufficient evidence that measures are in place to protect consumers from harm.

- There is sufficient evidence that where there is evidence of harm to consumers, action is being taken to adequately address issues and eliminate them.

Example Questions:

- Is there evidence of physical or mental harm from the provision of goods or services?

- Is there evidence of risk that is not being appropriately addressed?

- Is an identified harmful situation being communicated to those affected? If not, why? Should it be?

- If harm is being addressed, is it considering how to restore consumer trust and confidence?

Information - Is it accessible, accurate and useful?

Outcomes from applying the principle:

- Available information provides consumers with what they need to know to make good choices or to undertake action

- Information is easy to find and presented in a way that is easily understood

Example Questions:

- Where is information stored? Does this meet everyone’s needs?

- Is information up to date?

- Is information simple to read and understand? Has it been Plain English-ed (reading age of 9)?

- Does information adequately and appropriately signpost consumers to what they need to do next?

- Is information available in more than one language for those whose first language is not English?

- Is information available in more than one format?

- 'Is information set out in such a way as to support consumers to make good choices based on accurate, accessible and clear narrative.'

Fairness - Are all consumers treated equally, honestly and justly?

Outcomes from applying the principle:

- Goods and services are inclusive

- Goods and services are delivered or sold in a way that does not discriminate between individuals or groups of consumers

Example Questions:

- Is there evidence that any specific consumers or groups of consumers (people, households, or businesses) are excluded from qualifying to receive goods or services?

- Are exclusions from goods, services or support justified?

- Are consumers being impacted by a change in policy? Is this being managed to reduce or eliminate detriment? For example, low income or rural consumers.

- Is there a need to highlight concerns to government, beyond policy and decision making within a market?

- Are public services being prioritised over profits?

- Is policy and decision making adequately informed? Is it using robust consumer evidence or data or is it imbalanced in its conclusions?

- Are or will organisational or political agendas impact upon some individuals or groups of consumers?

- Are some groups of consumers being asked to pay more to support other groups of consumers, which is causing financial hardship?

- Are current consumers being asked to pay a fair share or will future consumers pay for legacy costs?

- Is what consumers are being asked to pay fair, proportionate and timely?

Representation - Do consumers have a meaningful role in shaping how goods and services are designed and provided?

Outcomes from applying the principle:

- There is evidence that consumers are informing the design and delivery of current and future goods and services

- Organisations can evidence where consumers have influenced outcomes

Example Questions:

- Are communities involved in the planning and delivery of services early enough in the process?

- To what degree are decisions being made that have been informed by consumer research, engagement, or data?

- Is customer or community engagement robust and meaningful, rather than tokenistic? How is this evidenced?[37]

- Can an organisation evidence where consumer input has influenced outcomes?

- Can customers or communities identify where their input has influenced decision making and final outcomes?[38]

- Is there evidence that better or more consumer input earlier in a process may have avoided consumer harm?

Redress - If things go wrong, is there an accessible and simple way to put them right?

Outcomes from applying the principle:

- Consumers are clearly signposted to redress support services and procedure.

- Redress procedures are clear and simple to engage with.

- There is clear commitment to resolve consumer issues where a complaint has been raised or where a customer has raised an informal concern.

Example Questions:

- Are redress commitments / service standards fair and clear?

- What commitment has been made by an organisation to resolve an issue where it accepts responsibility?

- Is there evidence that an organisation is not accepting responsibility where it is clearly their fault?

- Is there evidence that an organisation is not following its own redress process openly and fairly?

7. Annex C: Engaging with consumers

This annex includes examples of consumer engagement that public authorities subject to the duty can refer to when determining the best way to meet the duty.

It is not an exhaustive list and you are encouraged to seek out and share examples from relevant stakeholders you are engaged with.

It is also not a fixed list which will develop over time as more consumer engagement examples, especially those specific to meeting the duty, become available. You are encouraged to share these examples with Consumer Scotland, either through the consultation process[39] or directly.

Consideration should be given as to how a strategic decision affects individuals and communities as a whole and the difference between the two. Citizens Advice Scotland conducted work into engaging with communities[40] for example, it found that the engagement should:

- Be inclusive, accessible and representative

- Ensure communities are fully involved in engagement programmes as early as possible

- Establish communities’ trust and confidence in engagement programmes

- Tailor engagement methods to individual communities

- Flexible to respond to and incorporate community ideas and needs

Example 1 – The Scottish Approach to Service Design

The Scottish Government has developed a framework on how it designs ‘user-centred public services’, the “Scottish Approach to Service Design”[41] (SAtSD).

The SAtSD encourages engagement with users before a solution or service is decided upon. Consumers should be supported and empowered to actively participate in the design and delivery of their services.

The founding principles of SAtSD emphasise designing services around people and citizen partnership:

- We explore and define the problem before we design the solution.

- We design service journeys around people and not around how the public sector is organised.

- We seek citizen participation in our projects from day one.

- We use inclusive and accessible research and design methods so citizens can participate fully and meaningfully.

- We use the core set of tools and methods of the Scottish Approach to Service Design.

- We share and reuse user research insights, service patterns, and components wherever possible.

- We contribute to continually building the Scottish Approach to Service Design methods, tools, and community.

These principles of service design are an example of how to ensure consumer engagement is at the heart of designing services for consumers. They can therefore help improve outcomes for consumers and help public authorities meet the consumer duty.

Example 2 – Post-Covid-19 Futures Commission

The Royal Society of Edinburgh’s Post-Covid-19 Futures Commission spent eighteen months exploring four themes of the coronavirus outbreak, one of which was ‘inclusive public service’. [42]

The inclusive public service working group asked the questions ‘what can we learn in terms of practices, approaches and outcomes of those delivering person-centred public service across Scotland?’ and ‘what change is possible in the near future?’.[43]

Some of the findings included:

- Urgent change is needed to Scotland’s public service to put people at the centre, giving everyone the help and support they need to live a full life.

- The Covid-19 crisis highlighted Scotland’s deep and longstanding inequalities.

- We are a rich country, but we spend too much public money on propping up old systems designed for a different time.

- We need to ask: ‘What matters to you?’ instead of: ‘What’s the matter with you?’

The Commission also called for more use of a ‘social prescribing’ approach to healthcare as a priority.[44] Social prescribing allows healthcare workers to encourage patients to try community based solutions, outside of traditional health services where it would better meet patients' needs.

This is an example of thinking outside of the box and securing the best outcome for consumers, rather than focusing on established systems and ways of doing things.

8. Annex D: Publication requirement

The 2020 Act requires relevant public authorities to publish information at least annually about the steps taken to meet the consumer duty. One of the suggested methods about how to do this is to make a statement in the authority’s annual report.

A suggested pro forma template for making this statement is included below. Public authorities subject to the duty will perform a wide variety of functions and be subject to various other duties and statutory requirements, it may therefore be necessary, and will be acceptable, to make changes to the approach below to make the final statement more relevant to you organisation.

Consumer duty annual report example

[your organisation] is considered a relevant public authority per the Consumer Scotland Act 2020 (relevant public authorities) regulations 2024.[45] This means that we must meet the four requirements of the Consumer Scotland Act 2020:

- When making decisions of a strategic nature, have regard to the impact those decisions have on consumers

- When making decisions of a strategic nature, have regard to the desirability of reducing harm to consumers

- Publication of information about the steps taken to meet the duty

- Having regard to the Consumer Scotland guidance on how to meet the consumer duty

We have met all of the requirements of the 2020 Act during this year/period. [information on how you have met the requirements e.g. following the impact assessment process in the guidance document, or a different approach, when making strategic decisions; and making this annual report statement].

This means that we have put consumer outcomes at the heart of our strategic decision making by having regard to the impact those decisions have on consumers and to the desirability of reducing harm to consumers. [you may wish to give examples of specific strategic decisions and the outcome on consumers].

Or

We have not met all of the requirements of the 2020 Act during this year/period. [information on what requirements have not been met and why].

[Information on the changes your organisation will make to meet the consumer duty in future].

9. Annex E: Assessment not required template

Consumer Scotland has provided an example template that could be used to record that a duty impact assessment is not required for a strategic decision.

The template should be authorised by an appropriately senior member of staff (Accountable Officer or equivalent), recognising that meeting the consumer duty and improving outcomes for consumers is a priority for the organisation.

A Word version of the assessment not required template can be downloaded from the Publications section of the Consumer Scotland website.

10. Annex F: Impact assessment

Consumer Scotland has provided an example impact assessment template for completing the impact assessment. The document includes examples of completed assessments. A Word version of the Consumer duty example impact assessment can be downloaded from the Publications section of the Consumer Scotland website.

11. Annex G: Evaluation tool

Consumer Scotland has provided an example evaluation template that could be used by a public authority to review their approach to the consumer duty and evaluate whether a different approach would be more effective in future.

A Word version of the example Consumer duty evaluation template can be downloaded from the Publications section of the Consumer Scotland website.

12. Endnotes

[1] Section 25 of the 2020 Act: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2020/11/pdfs/asp_20200011_en.pdf

[3] In accordance with section 22 of the Consumer Scotland Act 2020

[4] The person(s) or organisation(s) with responsibility for overseeing the strategic direction of the entity and obligations related to the accountability of the entity. Senior decision makers may include management personnel, for example, executive members of a governance board, or politically elected members of a government or local authority.

[5] How to meet the consumer duty: guidance for senior decision makers (draft)

[8] https://www.gov.scot/publications/consultation-consumer-duty-public-bodies/pages/6/

[9] Consumer Scotland Bill policy memorandum: https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/current-bills/consumer-scotland-bill/introduced/policy-memorandum-consumer-scotland-bill.pdf

[11] See also: the public sector equality duty in the Equality Act 2010 (https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents) and the Scottish Specific Duties (https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ssi/2012/162/contents/made). The public sector equality duty is a duty on public authorities to consider how their policies or decisions affect people who are protected under the Equality Act 2010

[12] See also: the Fairer Scotland Duty (https://www.improvementservice.org.uk/products-and-services/consultancy-and-support/fairer-scotland-duty) which places a legal responsibility on named public bodies in Scotland to actively consider (‘pay due regard’ to) how they can reduce inequalities of outcome caused by socio-economic disadvantage, when making strategic decisions

[13] See for example: https://www.eastlothian.gov.uk/downloads/download/12542/integrated_impact_assessment_guidance; https://www.aberdeenshire.gov.uk/council-and-democracy/equalities/equality-impact-assessments/

[16] The person(s) or organisation(s) with responsibility for overseeing the strategic direction of the entity and obligations related to the accountability of the entity. Those charged with governance may include management personnel, for example, executive members of a governance board, or elected members e.g. of a local authority

[18] How to meet the consumer duty: guidance for senior decision makers (draft)

[19] https://www.gov.scot/policies/improving-public-services/

[20]https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/pillars/Spectrum_8.5x11_Print.pdf

[21] 010420StrategicPlanCustomerInsightsDocV15.pdf (scottishwater.co.uk)-

[23] https://www.scottishwater.co.uk/About-Us/What-We-Do/Independent-Customer-Group

[24] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents

[25] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ssi/2012/162/contents/made

[26] https://fairbydesign.com/inclusive-design/

[29] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2020/11/section/23/enacted

[30] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/sdsi/2024/9780111058855

[31] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2020/11/section/21/enacted

[32] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2020/11/section/24/enacted

[33]“Small business” Is defined by section 38 of the Small Business, Enterprise, and Employment Act 2015

[34] https://www.gov.scot/publications/consultation-consumer-duty-public-bodies/pages/3/

[35] https://commission.europa.eu/publications/understanding-consumer-vulnerability-eus-key-markets_en

[36] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/15/section/2/enacted

[37] E.g. see the Community Empowerment Scotland Act 2015

[38] See Citizens Advice Scotland: https://www.cas.org.uk/publications/engaging-hearts-and-minds-study-conducting-successful-engagement-communities-and

[39] Consultation

[41] https://www.gov.scot/publications/the-scottish-approach-to-service-design/pages/about-this-resource

[42] https://www.rsecovidcommission.org.uk/working-group-summary-reports/

[45] The Consumer Scotland Act 2020 (Relevant Public Authorities) Regulations 2024 (legislation.gov.uk)