1. Overview

As we enter the coldest months of the year, the scheduled increase to the energy price cap from 1st October[i] underlines the need for action to support households struggling with energy costs. Short-term action is needed to ensure support is in place before this winter. Therefore, any affordability intervention this winter will need to make use of existing mechanisms (such as the Warm Home Discount scheme) to deliver within this timeframe.

In addition to the consumer groups who disproportionately report energy affordability challenges (see Section 3), recent changes to winter support arrangements[ii] mean that people who do not claim benefits that they are eligible for will also be particularly impacted. A package of short-term support, though existing schemes this winter, should therefore be complimented by efforts to encourage uptake of passport benefits, such as Pension Credit.

Thinking beyond this winter, this paper focuses on the need for better designed and targeted energy affordability policy to be delivered in the longer-term. The current range of affordability interventions have been developed gradually, often in response to specific challenges at a given time. They do not represent a joined-up, structured set of policies, based on a systematic understanding of consumer need and how it can best be addressed. For example, the current proposal to shift the recovery of some operational costs from standing charges onto the unit rate risks increasing the cost burden on consumers who have a high essential energy expenditure (see Section 3 for the consumer groups this includes) and is therefore not an effective response to energy affordability challenges.

Households with above median consumption would also lose out from any rebalancing of costs from standing charge to the unit rate, and this is likely to disproportionately include consumers in Scotland. Due to the cold and wet climate, and households’ exposure to the elements in rural areas, consumers in Scotland are likely to have increased energy requirements for longer over the course of the year.[iii]

The development of energy affordability policy which maximises value, and ensures that support reaches those who need it most, requires:

- better data, to improve targeting and to overcome data-matching issues

- a holistic review of existing support arrangements

- that any redesign be based on clear consumer-focussed actions (see Section 4)

2. Context

Energy is an essential for life service, which all consumers require in order to heat and power their homes. Households are placed at risk of significant harm when they are unable to afford their energy bills and access satisfactory levels of heat or other energy uses in their home.[iv] This harm may include:

- a range of adverse health effects (such as increased stroke risk, respiratory issues or pain management)

- rationing and its related impacts

- the mental health impact of both underheating and energy debt

- the educational attainment gap which results from children living in cold homes[v][vi][vii]

Energy affordability is a significant social policy issue across Great Britain, with responsibility for energy affordability policy straddling reserved and devolved competency. These interventions include:

- Energy Price Cap: although not intended as an affordability intervention, the price cap limits the standing charge and unit rate on suppliers’ standard variable (default) tariff for gas and electricity.

- Winter Fuel Payment: a payment of between £200 and £300 made via bank transfer. The intervention was previously available to all pensioners born before the date of birth for eligibility. The change of eligibility means recipients must be in receipt of Pension Credit or other qualifying benefits. The total cost of policy is: £180m a year in Scotland, though the eligibility change will significantly reduce this cost.[viii] This payment is due to be devolved in Winter 2025-26 to Scottish Government’s Pension Age Winter Heating Payment.

- Winter Heating Payment: a Scottish Government benefit which provides £58.75[ix] per year to those in receipt of qualifying benefits to help with heating costs. The Winter Heating Payment replaced the Cold Weather Payment. Total cost of policy is £19.7m per year in Scotland.[x]

- Child Winter Heating Payment: a Scottish Government benefit which provides £251.50 per year to disabled children and young people and their families to help with heating costs. Total cost of policy is £5.7m per year in Scotland.[xi]

- Warm Home Discount: a GB-level scheme which provides a one-off £150 discount to consumers’ energy bills. In Scotland, eligibility related to qualifying benefits for the Broader Group is applications-based which means that not all qualifying customers will receive the discount.[xii] Total cost of policy is approximately £50 million per year in Scotland levied on consumers’ energy bills.[xiii]

- Other crisis funding: available through the Scottish Welfare Fund and previously the Fuel Insecurity Fund – a Scottish Government programme which ended in 2024.[xiv]

Despite these measures, energy costs remain unaffordable for a significant number of consumers in Scotland. Consumer Scotland’s most recent Tracker survey, in Winter 2023-24, found that 26% of consumers reported that it was difficult to keep up with energy bills.[xv] Similarly, fuel poverty rates in Scotland rose from 24.6% in 2019 to 31% in 2022.[xvi]

Prices rose to historic highs during the energy crisis and exposed the extent to which certain groups of consumers are impacted by energy costs. The government implemented an emergency response to the crisis to shield consumers from the extent of the price increases, such as the Energy Price Guarantee and the Energy Bill Support Scheme.[xvii]

However the enduring absence of an overarching and detailed view of consumer needs and lack of holistic data sets meant that neither suppliers, Ofgem or government had an appropriately detailed picture of the consumers most at risk from the energy crisis, or the level of support required to effectively mitigate its effects. This led to a need for broad interventions with insufficient focus on the needs of vulnerable groups, and a reliance on crude and imperfect proxies to aid with targeting.

3. Distributional impacts of energy affordability challenges

Evidence from Consumer Scotland’s Energy Affordability Tracker and engagement with frontline agencies in Scotland[xviii] has shown that the following groups of consumers are particularly at risk of energy affordability challenges, including energy debt:

- Disabled people – particularly those limited a lot by disability

- Those on a low income

- Those with children under 5

- Those on prepayment meters

- Those using traditional electric-only heating or heating oil

The energy crisis not only highlighted which groups of consumers were vulnerable to increased energy costs, it also exposed the gaps in existing support measures. Our Energy Tracker survey repeatedly shows that a substantial minority of consumers in Scotland struggle to afford their energy bills, which suggests that the current framework of support does not provide a sufficient package of measures and that those which are in place are too narrowly designed to provide help to all who may need it[xix].

Furthermore, levels of energy debt amongst consumers have risen considerably during the past three years. Ofgem’s most recent GB-wide figure of £3.7bn owed to energy suppliers demonstrates the scale of the domestic energy debt challenge.[xx] Our Tracker survey found that nearly 1 in 10 consumers self-reported being in energy debt, including indirect energy debt (such as using a credit card or borrowing money from a friend to meet energy costs). This poses additional challenges to the affordability of energy for these consumers, who will be required to pay back their debts while simultaneously paying for their ongoing energy use.

4. The need for a new approach

The current range of affordability interventions have been developed gradually, over a period of time, responding to particular pressures and opportunities. They do not represent a joined-up, structured set of policies, based on a systematic understanding of consumer need and how it can be best addressed. Therefore, a holistic review of existing support arrangements would ensure funding is targeted effectively to those that need it most.

Consumer Scotland has identified five key actions to underpin future policy:

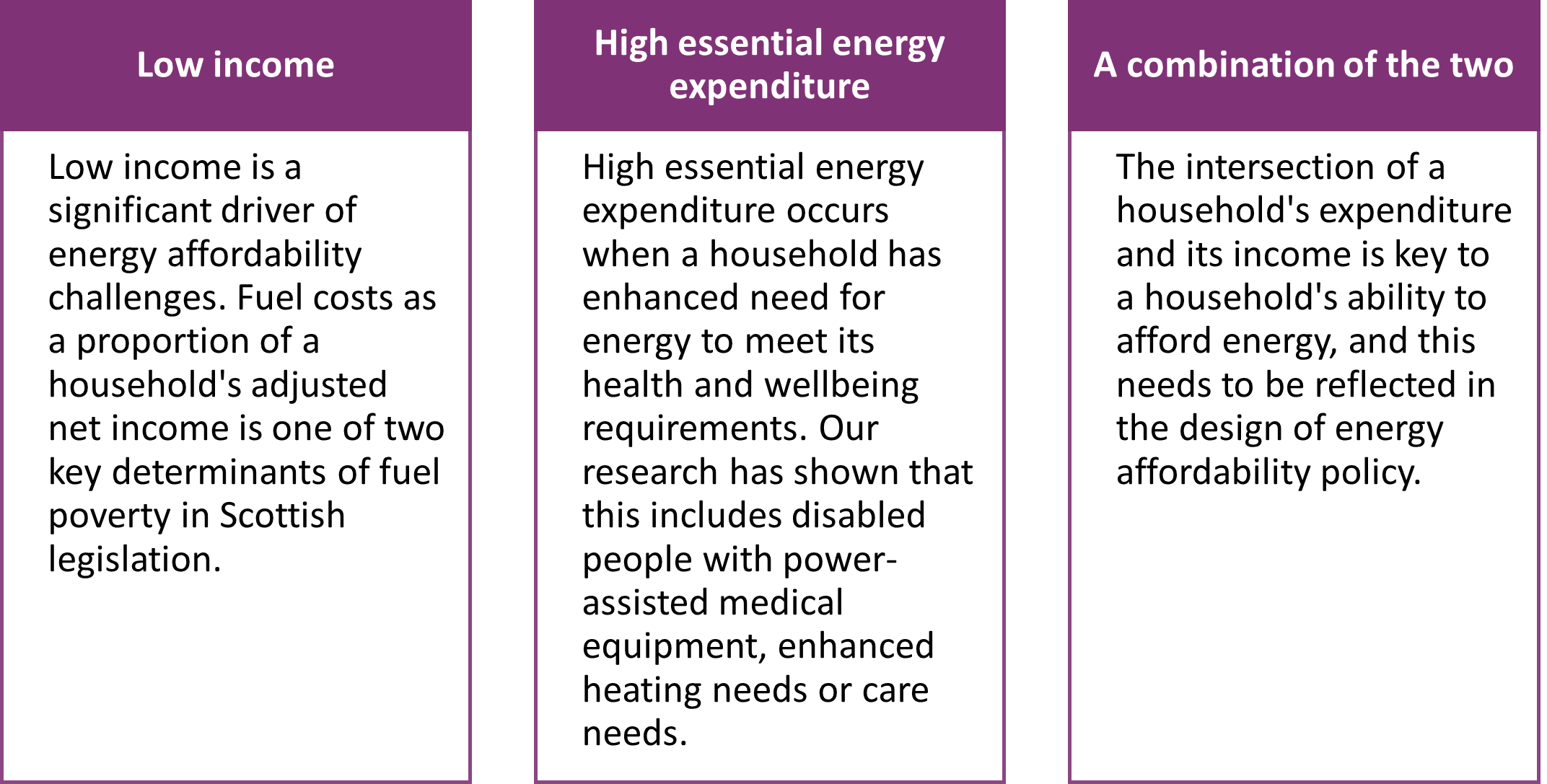

1. Targeted interventions for consumers should be designed around an understanding of low income alongside high essential energy expenditure

Energy affordability policy should consider both income and high essential energy expenditure as indicators to ensure that targeting is able to effectively mitigate affordability challenges for key consumer groups – see Figure 1. [xxi]

Figure 1: Considerations for income and energy expenditure in determining energy affordability

2. A holistic review of existing support should inform the design of future affordability policy

A holistic review of existing energy affordability policy will be a key step in determining the best use of funding to ensure that all consumers who need support are able to receive it. There are various schemes across reserved and devolved competencies which are aimed at alleviating fuel poverty and/or tackling energy affordability challenges, including energy bill support and social security. The scheduled end of the Warm Home Discount scheme in March 2026 presents an opportunity to review the bill levy-funded support offered to consumers in vulnerable circumstances and how to ensure that funding delivers maximum impact in terms of improving consumer outcomes.

3. Design of energy affordability support must be futured-proofed

Tariffs of the future are likely to be increasingly complex as suppliers innovate to provide competitive offers tailored for different technologies and heating systems. Therefore, energy affordability policy needs to be future-proofed to ensure that it is compatible with future tariff design such as dynamic time/type of use. There may be complexities that need to be worked through when, for e.g., applying a unit rate discount to complex tariffs.

4. Affordability interventions should be fully costed with fair distribution of costs for consumers

Support has tended to be energy bill or taxpayer funded. There is a need to ensure that energy affordability policy costs are not burdensome to particular groups of consumers. Therefore, any future affordability support needs to be fully costed, with analysis of impacts on consumer bills, including distributional analysis for different consumer profiles. For example, an increase in policy costs on energy bills is likely to increase energy bills for all consumers and potentially result in affordability challenges for those who are currently ‘just managing’.

5. Interventions must be practical and implementable

Future energy affordability policy needs to be practical and implementable and work through challenges for delivering support in Scotland. There is a need to first identify the key barriers and how to overcome them across GB.

Data-matching is one of the biggest challenges to implementing affordability policy in Scotland. Data-matching involves comparing computer records held by one organisation against other records held by the same or another organisation.[xxii] For example, in Scotland, data-matching challenges currently affect the delivery of the Warm Home Discount rebate to customers not in the Core Group.[xxiii] There needs to be concerted action to overcome these challenges if energy affordability policy is to be implemented effectively. Barriers to implementation could be overcome by a codesign approach with industry, or by convening an expert working group.

5. Recommendations

1. Governments and Ofgem to undertake a holistic review of existing energy support arrangements and implement energy affordability policy which maximises value and ensures that support reaches those who need it most. This should target consumers on a low income and certain groups of consumers with high essential energy expenditure.

2. Scottish Government to commit to data improvements, through a new data strategy, to improve its ability to target support and to overcome data-matching challenges. There are likely to be consumer benefits in joining-up approaches across essential services, including the water industry.

3. Governments and Ofgem to ensure that energy affordability policy is fully costed and underpinned by distributional analysis of the costs and benefits of proposed changes on different consumer groups.

4. Governments and Ofgem to test energy affordability policy with cross-industry stakeholders to ensure that proposals are practical and implementable.

5. UK Government to ensure that energy affordability policy is consistent with the objectives of retail market reform.

6. Endnotes

[i] £1,717 for a typical household, an increase of 10% from the previous review period

[ii] Changes to Winter Fuel Payment eligibility rules - House of Commons Library (parliament.uk)

[iii] National Energy Efficiency Data (NEED) shows that the median gas consumption for dwellings in Scotland has been consistently higher than in England and Wales over the last decade, and 7.8% higher in 2021.

[iv] The Cost of Keeping Warm: Lived Experience of Energy and Vulnerability in Scotland Pilot | Citizens Advice Scotland (cas.org.uk)

[v] read-the-report.pdf (instituteofhealthequity.org)

[vi] Health, Disability and the Energy Crisis | Consumer Scotland

[vii] Final version - Fixing the foundations - August 2024 v3 (ctfassets.net)

[viii] consumer-scotland-response-to-the-scottish-governments-consultation-on-pension-age-winter-heating-payment.pdf

[ix] Winter 2024-25 value; the Winter Heating Payment is adjusted in line with inflation

[xii] From 2022 (WHD Scheme Year 12), a data-matched Core Group 2 replaced the applications-based Broader Group in England and Wales

[xiii] Warm Home Discount Scotland: Guidance for Suppliers 2022 – 2026 V1 (ofgem.gov.uk)

[xiv] Budget: Sector hits out at ‘hammer-blow’ affordable housing cuts | Scottish Housing News

[xv] Insights from latest Energy Affordability Tracker: Causes and impact of energy debt | Consumer Scotland

[xvi] Scottish House Condition Survey 2021 (www.gov.scot)

[xvii] [Withdrawn] Energy Price Guarantee up to 30 June 2023 - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[xviii] Scottish Energy Insights Coordination Group Report (HTML) | Consumer Scotland

[xix] Insights from latest Energy Affordability Tracker: Causes and impact of energy debt | Consumer Scotland

[xx] https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/publications/debt-and-arrears-indicators

[xxi] Disabled people facing serious negative impacts from high energy bills | Consumer Scotland

[xxii] Draft_Code_of_Data_Matching_Practice.pdf (publishing.service.gov.uk)

[xxiii] Consumers in the Broader Group of the Warm Home Discount Scotland scheme still need to apply for a rebate, whereas the scheme in England and Wales is fully data-matched