1. Preface

With huge thanks to all the participants and organisations who took part in the workshops. Participants were invited if they had a particular Scotland-focus. With an additional thank you to Marie Curie for reviewing the draft report.

|

Workshop 1 |

Workshop 2 |

|

Carers Scotland |

Carers Scotland |

|

Carers Scotland |

Carers Trust |

|

Children’s Hospices Across Scotland (CHAS) |

Children’s Hospices Across Scotland |

|

Citizens Advice Scotland |

Coalition of Carers |

|

Coalition of Carers |

Two Disability Access Panels |

|

Disability Equality Scotland |

Energy Action Scotland |

|

Enable Scotland |

Macmillan Cancer Support |

|

Energy Action Scotland |

Marie Curie |

|

Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland |

MECOPP |

|

Inclusion Scotland |

One Parent Families Scotland |

|

Marie Curie |

RNIB Scotland |

|

Minority Ethnic Carers of People Project (MECOPP) |

|

|

Mental Health Foundation of Voices Experience (VOX) |

|

|

MND Scotland |

|

|

One Parent Families Scotland |

|

|

Research Institute for Disabled Consumers (RiDC) |

|

|

RNIB Scotland |

|

|

11 energy consumers who are disabled or living with a health condition or a carer |

|

2. Who we are

Consumer Scotland is the statutory body for consumers in Scotland. Established by the Consumer Scotland Act 2020, we are accountable to the Scottish Parliament. The Act defines consumers as individuals and small businesses that purchase, use or receive in Scotland goods or services supplied by a business, profession, not for profit enterprise, or public body.

Our purpose is to improve outcomes for current and future consumers, and our strategic objectives are:

- To enhance understanding and awareness of consumer issues by strengthening the evidence base

- To serve the needs and aspirations of current and future consumers by inspiring and influencing the public, private and third sectors

- To enable the active participation of consumers in a fairer economy by improving access to information and support

Consumer Scotland uses data, research and analysis to inform our work on the key issues facing consumers in Scotland. In conjunction with that evidence base we seek a consumer perspective through the application of the consumer principles of access, choice, safety, information, fairness, representation, sustainability and redress.

We work across the private, public and third sectors and have a particular focus on three consumer challenges: affordability, climate change mitigation and adaptation, and consumers in vulnerable circumstances.

3. Executive summary

Energy is an essential ‘for life’ service which every person depends upon. The energy crisis has highlighted that certain consumers are particularly exposed to high energy prices and price shocks. Consumer Scotland recently published a position paper on the future direction of targeted energy affordability policy. One of our core recommendations is that a future energy affordability policy should be targeted to households with high essential energy expenditure as well as those on a low income.

Disabled people and those with health conditions are groups of consumers who often have higher energy needs with the potential for significant detriment if they have to ration or cut back. This report considers different options for delivering additional support for disabled consumers.

High essential energy expenditure is an often overlooked component of affordability, and income-related support does not tend to account for energy need and the impact of this on expenditure[1][2][3]. High essential energy expenditure is energy usage which is necessary to meet needs that are essential to the health and wellbeing of the individual. For disabled people, this expenditure might include: medical equipment, mobility equipment, essential care needs and operating an appropriate heating regime.

The focus on disabled consumers is not at the exclusion of other groups Consumer Scotland has identified as having high energy expenditure or who need to be supported through future energy affordability policy. However, disabled consumers can have particular requirements as a result of the way that they use energy and may have specific preferences for how energy support is delivered and accessed.

There are significant benefits to targeted energy support for the health and wellbeing of disabled consumers and those with health conditions. Improved affordability and access to essential to life heat and power means that people are able to better maintain their health and wellbeing. The prevention of illness also reduces the burden on the National Health Service in relation to excess winter deaths and cold-related hospital admissions.

Improved affordability of energy bills would support the prevention of debt and arrears, self-disconnection from energy supplied by prepayment meters and improvement in debt-related mental health issues.

Consumer Scotland conducted workshops with both experts by experience (disabled people and those with health conditions) and organisations who represent them, to gather evidence and inform our understanding of the affordability challenges faced by disabled consumers and what interventions may support them.

Our approach was underpinned by the social model of disability and actively included disabled people within the discussions on affordability and support, reflecting the ‘nothing about us without us’ principle with the aim of embedding lived experience within policy design.

Across the workshops, there was evidence that disabled consumers are more likely to have high essential energy expenditure, supported by Consumer Scotland analysis of the Scottish Household Survey which has shown that disabled consumers whose activity limits them a lot have an associated £124 additional energy expenditure annually when controlling for other potentially explanatory characteristics[4]. It should be noted that the figure will vary considerably depending on disability and that it is based on actual expenditure rather than energy need so does not take account of self-rationing.

Additionally, between Consumer Scotland appraisal of existing policy, and participants insight, two important gaps in existing support were:

- Working age disabled people are amongst the consumer groups most likely to miss out on energy-related support when looking across all consumers and who receives support. This is due to low levels of targeting support at disabled people who are of working age, with support focussed on income (via passport benefits). Support is designed to offset the impacts of low income but does not account for higher levels of expenditure associated with a disability.

- The limited recognition given to the drivers, implications and impacts of high essential energy expenditure means that support often misses this key driver of affordability challenges for disabled people.

The final workshop examined different energy affordability support options. These included: an energy social tariff; changes to the Winter Fuel Payment; expansion of Warm Home Discount; expansion of Child Winter Heating Assistance; the Warm Home Prescription and rebates on medical equipment.

The energy social tariff was identified by participants as the most preferred option. The participants outlined key benefits and challenges for the options. There are opportunities in the immediate and longer-term to improve outcomes for disabled consumers:

- Targeted energy support which considers high essential energy expenditure offers an opportunity to reduce vulnerability and improve consumers’ experience of the energy market. This includes reducing energy debt and arrears.

- Broader interventions, such as energy efficiency programmes, more inclusive market design and improvements in signposting, also offer the opportunity improve the support available for disabled people and those with health conditions

Additional findings from the final workshop found that:

- The existing support landscape within the GB energy market is complex. A wider holistic review and better targeting of existing support could ensure future affordability support reaches everyone who needs it.

- Data matching and availability is the biggest barrier to effective support, with no perfect way currently existing to capture high essential energy expenditure amongst consumers.

Participants identified several features, therefore, that they would want to see in the design of targeted energy affordability support for disabled people. These are:

- A compassionate, person-centred approach

- Reducing the onus on the consumer to access support they are eligible for, particularly by automating access to support (e.g., through data matching)

- Trusted intermediaries are essential for linking consumers in vulnerable circumstances with support but participants also raised concerned about healthcare workers determining who can receive support without welfare training, or where relationships may already be strained

- Frontloaded support which ensures that people are provided with financial support before the cost is incurred, rather than having to claim it back afterwards

- Tapered or stepped support that avoids cliff edges. A cliff edge is where a slight increase in income may result in loss of access to specific benefits/support such as energy bill support

Additional findings from the workshops were that there is a potential solution to address the significant increased costs faced by terminally ill people. A proportion of this energy use is likely to be classed as medical dependency (e.g., hospice beds, ventilators, feeding pumps, nebulisers and oxygen saturation monitors)[5]. There is potential to use Benefits Assessment for Special Rules in Scotland (BASRiS) eligibility to identify those who are terminally ill. This group is proportionately much smaller and therefore, may be a more achievable policy for the Scottish Government to administer and fund.

Looking to the future of energy policy, energy pricing policies risk exacerbating inequality and further marginalizing a vulnerable group of consumers without active inclusion of disabled people’s needs.[6] Embedding the social model approach, and actively including the lived experience and expertise of disabled people, is critical to ensuring the principle of ‘nothing about us without us’. By incorporating these perspectives, energy policy can more effectively reflect the diverse experiences of disabled individuals and address the barriers they face, leading to a more inclusive and equitable energy market.

Recommendations

To address the challenges for consumers set out in this report, Consumer Scotland recommends:

1. The Scottish and UK governments and Ofgem should clearly recognise in relevant policy documents and activities, the significance of ‘high essential energy expenditure’ as an important driver of energy affordability challenges for disabled consumers. For disabled people, this is primarily related to those essential for health and wellbeing needs which are additional to those of a non-disabled consumer.

Recognition of this affordability driver should be applied to consideration of any reform to existing market structures (e.g., standing charges or levy rebalancing) and to future market design (i.e., changes needed for increased electrification and development of a future social tariff).

2. The Scottish and UK Government should undertake a holistic review of existing energy affordability interventions and examine the options for developing interventions which are targeted at disabled people and those with health conditions who have higher essential energy needs. This could be done through:

- Better targeting of existing fuel poverty and energy affordability schemes to include disabled people (for example, Winter Fuel Payment) AND

- Inclusion of disabled people within the design of future targeted energy affordability support

3. The Scottish Government should consider opportunities to provide additional energy affordability support targeted at those who are terminally ill. This may be primarily based on those receiving Personal Independence Payment/Adult Disability Payment[*] under the Special Rules for Terminal Illness (i.e., SR-1 or BASRIS)[†]. There may be options to design this support to specifically reach those who are end-of-life via Adult Disability Payment.

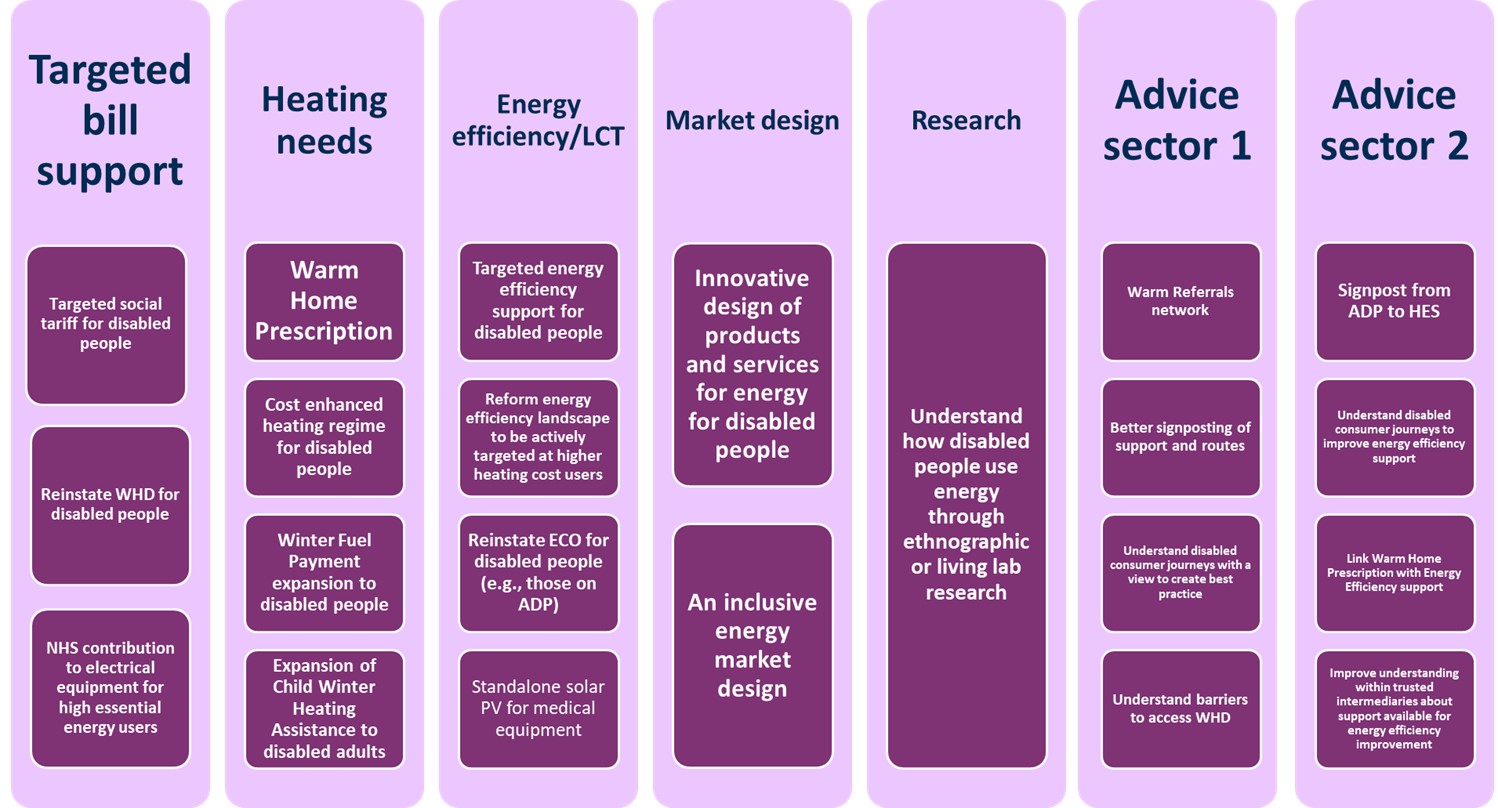

4. A cross-industry approach, (e.g., UK and Scottish governments, regulator, energy suppliers and networks) to proactively consider how disabled consumers’ needs may be better met in the energy market (including areas such as energy efficiency and low carbon technology). This includes increased access to energy efficiency and low carbon technology (See figure 1 on page 32 for overview of policy suggestions from the workshops).

4. Introduction

Rationale and scope

Energy is an essential ‘for life’ service which every person depends upon. The energy crisis has highlighted that certain consumers are particularly exposed to high energy prices and price shocks. The resulting impacts of high energy prices can include significant risks to the health and safety of some disabled people and those with health conditions. Consumer Scotland’s Energy Affordability Tracker has highlighted the consistently disproportionate impact of high and volatile energy bills on disabled consumers – especially those who are limited a lot by their disability.

Consumer Scotland uses the term ‘targeted energy support’ to refer to any financial support aimed at alleviating energy affordability challenges, but not including energy efficiency programmes. Our recent policy paper[7] determined that future energy affordability policy should target consumers with low income and certain groups of consumers with high essential energy expenditure. Disabled consumers are a group who often have higher energy needs with the potential for significant detriment if they have to ration or cut back on their energy use.

Consumers who face an intersection of different social (e.g., age, disability, young children or single parents, rurality) and technological factors (e.g., prepayment users, metering types, poor energy efficiency or access to tariffs) that increase their energy expenditure are likely to face even more acute impacts. Ofgem already has a statutory duty to consider the needs of disabled people, those who are chronically sick, of pensionable age, living in rural areas and on a low income.[8]

|

“We need to look at what’s the cost of not supporting because we are talking about exacerbating impairments, more GP time, more NHS time.” – workshop 1 participant |

There have been a number of useful recent studies which have examined the opportunities and challenges involved in designing an energy social tariff, or other forms of targeted energy support, which can reach low-income consumers[9][10][11][12][13]. Proposals for how such support should be designed and delivered have varied between different organisations and the term ‘social tariff’ has been used and defined differently across different studies. Examples have included unit rate discounts (taken off price per unit of energy) and flat rate discounts (set amount taken off overall bill). These can be funded either through taxation or levies on consumers’ energy bills.[14][15][16][17][18]

Consumer Scotland advocates for targeted financial support for energy consumers on a low income[19]. Proposed interventions to date have largely relied on some form of income-related-measure which uses either benefits or income data to identify eligible consumers.

However, in addition to income alone, there is a need for any targeted intervention to be designed to also take into account the particular circumstances of consumers with high essential energy expenditure[20]. Essential energy expenditure refers to the costs resulting from energy usage which is necessary for the health and wellbeing of the individual (Box 2). Whilst poor energy efficiency can contribute to higher levels of energy use, other drivers of high essential energy needs, that are specific to disabled consumers or those with limiting conditions, are less well accounted for. These can include: power-related medical equipment, mobility equipment, essential care needs enhanced heating requirements).

There has been less work done on how targeted financial support may be expanded to better include those with high essential energy expenditure, such as disabled consumers. The devolved nature of particular social security benefits, along with strategy related to fuel poverty in Scotland, opens up alternative options for energy-related support in Scotland, alongside opportunities within the GB energy market or at a UK level.

This report considers different options for delivering additional support for disabled energy consumers. This specific focus on disabled consumers is not at the exclusion of other groups of consumers that Consumer Scotland has identified as having high energy expenditure, or who need to be considered in the design of future energy affordability policy. However, disabled consumers have particular requirements as a result of the way that they use energy and may have specific preferences for how energy support is delivered and accessed.

Now is an opportune moment to consider how future affordability policy could be better designed to meet the needs of the disabled consumers in Scotland. Particularly, there is an opportunity due to some key disability benefits being devolved (e.g. Child and Adult Disability Payment) and the wider policy developments around targeted energy support (sometimes referred to as a ‘social tariff’).

The purpose of the report is to examine how the needs and preferences of disabled consumers can be better designed into energy affordability policy. The report considers both the scope to target support for energy bills, and how future retail market reform more generally can be the catalyst for improved outcomes for those with high essential energy expenditure. The report does not seek to propose a specific ‘social tariff’ but to consider how a variety of approaches to providing energy bill support or making wider market reforms would meet the needs of disabled consumers.

The report’s findings have been informed by workshops and meetings with disabled people and disabled people’s representative organisations. These engagements have been supplemented with policy appraisal analysis by Consumer Scotland.

Box 2: High essential energy expenditure

The costs resulting from energy usage which is necessary for the health and wellbeing of the individual. For disabled people, there may be costs additional to those typically accrued by non-disabled people, including, but not limited to:

- Medical equipment (e.g., oxygen concentrators, at home dialysis, hoists, hospice beds) which are also likely to reflect power-related medical dependency

- Mobility equipment (e.g., electric wheelchairs, scooters)

- Essential care needs (e.g., increased washing needs, increased bathing needs, cost of carers in home such as heating requirements)

- Operating an appropriate heating regime (e.g., enhanced temperatures or heating hours) which includes the need for heat to manage medical conditions including pain, respiratory risk, fatigue

|

46% of disabled people (limited a lot by disability) reported it was difficult to keep up with energy bills compared with 21% of non-disabled people |

Social Model of Disability

Consumer Scotland has adopted the social model of disability, in keeping with best practice outlined by disability organisations, and a model driven by disabled people.[21] The social model of disability views people as disabled by the barriers that they face in society. By contrast, a medical model of disability would view people as disabled by their impairments or differences.[22] For example, a building can be designed in a way that is inaccessible and exclusionary if it does not have a suitable ramp or accessible toilets.

The social model recognises that disabled people across the world are marginalised in their attempts to access services and gain social protection.[23] An energy market which does not account for the needs and experiences of disabled consumers risks further entrenching these disadvantages or missing the opportunity to improve outcomes for disabled consumers.[24]

"My major worry [...] is that it then medicalises disability when a lot of us have spent a lot of time trying to move away from that" - workshop 1 participant

5. What we did

Consumer Scotland conducted a series of workshops to gather evidence to inform its understanding of affordability challenges faced by disabled energy consumers and what interventions may support them.

Our approach

Our approach was underpinned by the social model of disability and actively included disabled people within the discussions on affordability and support, reflecting the ‘nothing about us without us’ principle with the aim of embedding lived experience within policy design..

Research timeline

The research followed two phases:

Phase 1: Initial evidence gathering:

- Gathered input from the Scottish Energy Insights Coordination (SEIC) group and other key stakeholders[25]

- Consumer Scotland included explicit questions on disability and the impact on health within our Energy Affordability Tracker

- Engaged with an established third sector working group

- Carried out analysis of Scottish Household Survey data to try and establish the extent of the issue

Phase 2: Collaborative workshops:

Consumer Scotland commissioned Collaborate UK to undertake workshops with disabled people, and organisations representing disabled people, within Scotland. These workshops included experts by experience (see box 2).

|

Box 2: Defining Experts by Experience Consumer Scotland aim to ensure that our work is informed by the lived experience of consumers. When referring to consumers who participate in these activities we use the term ‘Experts by Experience’ recognising their knowledge, skills and expertise. A number of measures were applied to ensure the workshop was conducted in an accessible, inclusive and ethical way. For example, participants were asked to identify their individual accessibility needs at the recruitment stage so the facilitators could respond to them in the organisation and running of the research. On the day, the break-out groups were arranged so that most people with lived experience of disability, having a health condition or caring responsibilities were together in order that they would feel comfortable to share their experiences. We also applied the social model of disability to how the discussions were framed, which is based on identifying and addressing the structural barriers and additional detriment faced by those with disabilities and long-term health conditions due to the way society is organised. Participation was recognised financially via shopping vouchers and we also covered travel costs. The report was shared with participants for agreement prior to final publication and we are planning to continue to update our Experts by Experience on how we have acted on the research. |

Phase 3: Appraisal and analysis:

Building on the outcomes and input of the workshops, Consumer Scotland undertook internal work to appraise the merits and costs of proposed policies.

6. Findings

Disabled consumers are more likely to have high essential energy expenditure

The research identified a clear need to include those with high essential energy expenditure in targeted energy support. This includes disabled people and those with a health condition. Consumer Scotland’s analysis of the Scottish Household Survey has shown that disabled consumers whose activity limits them a lot have an associated £124 additional energy expenditure annually when controlling for other potentially explanatory characteristics[26]. However, it is important to note that this figure will vary considerably depending on disability and because it is based on actual expenditure, and not need, it does not account for circumstances where people have cut back on their energy use to detrimental effect.

High essential energy expenditure is an often-overlooked component of energy affordability challenges, as income-related support interventions do not tend to account for energy need and the impact that this has on expenditure.[27][28][29] This means that the value of support provided to a disabled consumer with high energy costs is the same as for those with lower energy requirements. At the same time, some disabled consumers who fall above the threshold for low income, and therefore are not eligible for some types of support, may also face significant affordability challenges driven primarily by high essential energy usage. A participant from workshop 1 reflected:

"It's not a singular, homogenous experience that people have, it changes depending on where you live and whether you've got gas for your heating or you've got electricity will make a huge difference financially, but it's the same level of financial support. And it's not based on net income so even if your expenditure [on energy] is considerably higher, because of the consequences of your condition, it's not looked at. It's not proportionate, the support has been provided does not recognise that differentiation despite knowing it to be true."

A finding from the workshop was a preference amongst participants for focussing on combined additional energy costs rather than a split between heating and electricity. Participants highlighted that many consumers do not make a distinction between these categories when considering energy need. Furthermore, some people may be on electric-only heating.

From the first workshop with disabled people and organisations that represent them, participants identified energy support which targeted both income and usage to reach those most in need, as being a favourable policy approach.

Participants also highlighted that there was complexity to considering different dimensions of high essential energy expenditure. One participant in workshop 1 noted that:

“Those that make decisions don’t actually see all the components. They just see heat, light and that’s it. That they don’t think about the washer and dryer and the other bit of equipment, and also the actual energy efficiency of the home’

|

Research by Marie Curie has shown bills can rise by as much as 75% after a terminal diagnosis due to essential energy use (Marie Curie (2024) One charge too many |

Working age disabled people are most likely to miss out on energy support

There are currently four sources of energy bill support potentially available to consumers in Scotland. These are:

- Winter Fuel Payment

- Warm Home Discount

- Winter Heating Payment

- Child Winter Heating Payment

Table 1 provides summary information on the eligibility criteria and number of recipients in Scotland.

- Winter Fuel Payment is a payment of between £150 - £300 per household. It has until now been universally available to individuals above the State Pension Age, but from this winter will be restricted to those in receipt of Pension Credit, i.e. pensioners on a low income. The Winter Fuel Payment is being devolved from the UK to the Scottish Parliament in April 2024 (and renamed Pension Age Winter Heating Payment (PAWHP)), although the UK government will continue to administer the scheme in Scotland for a transitory year[30].

- Warm Home Discount is an energy bill discount of £150 to recipient households. It is paid automatically to pensioner households in receipt of Pension Credit. In Scotland, working-age households who may be eligible for Ware Home Discount need to apply to their energy supplier to receive it. Broadly speaking, eligible households are those in receipt of low-income benefits as well as having various other characteristics of vulnerability (such as young or disabled children).

- The Winter Heating Payment and Child Winter Heating Payment are administered by the Scottish Government. Eligible recipients are those in receipt of various (mainly low-income) qualifying benefits.

Disability tends not to feature as a qualifying criterion in the existing landscape of energy support. The exceptions are the Child Winter Heating Assistance, for which receipt of a disability benefit is a qualifying criterion, and the Warm Home Discount, where disability can also be a qualifying criterion, although only alongside receipt of a low-income benefit.

What this means in practice is that:

- For working age households with a disabled adult, energy support is only available to low-income households in receipt of qualifying benefits. That support is designed to offset the impacts of low-income but does not account for any higher levels of energy expenditure associated with disability.

- For those above the State Pension Age, Winter Fuel Payment does account for the likely higher energy expenditure of older people related to heating although it is not linked to disability specifically. The planned restriction of Winter Fuel Payment to those on Pension Credit means there will no longer be support provided to pensioner households other than those who do not qualify for the full state pension, as both Warm Home Discount and Winter Fuel Payment are targeted at those in receipt of Pension Credit.

Table 1: Disability tends not to be a qualifying criterion for energy support

Eligibility criteria and key statistics for energy-related benefits in Scotland

|

Energy support scheme |

Eligibility criteria |

Amount |

Recipients (Scotland) |

Total cost (Scotland) |

|

Warm Home Discount |

Low income consumers (in receipt of certain qualifying benefits) |

£150 (Bill discount) |

88,000 households (core group) 168,000 households (broader group) |

£38 million |

|

Winter Fuel Payment (existing) |

Those aged above State Pension Age |

£150-£300 (Cash benefit) |

770,000 households (1m individuals) |

£180 million |

|

Winter Fuel Payment (new) |

Over 65s who are in receipt of Pension Credit |

£150-£300 (Cash benefit) |

137,000 households |

£32 million |

|

Child Winter Heating Payment |

Disabled children and young people and their families |

£251.50 (in 2024-25) |

30,000 persons |

£7.2 million |

|

Winter Heating Payment |

Persons in receipt of certain qualifying benefits and further requirements |

£58.75 (in 2024-25) |

418,000 |

£23 million |

Sources: Figures for Warm Home Discount are from the 2022/23 Scheme evaluation and pertain to that year[31]. Figures for Winter Fuel Payment are forecasts for 2024/25 prepared by the Scottish Fiscal Commission in August 2024[32]. Figures for Child Winter Heating Payment and Winter Heating Payment are estimates by Social Security Scotland[33].

Ensuring disabled consumers can meet their essential energy needs will have significant benefits

There are numerous potential benefits that targeted energy support for disabled consumers and those with a health condition might deliver:

- Improved access to an essential for life service: many disabled people, and people with a health condition, rely on medical equipment or have enhanced heating requirements to meet their needs. Making energy more affordable would mean that people are better able to maintain their health and wellbeing.

- Dignity and comfort: a warm home and sufficient power to meet basic needs are fundamental to people’s dignity and comfort. A cold home or an inability to meet basic needs can result in people living in difficult circumstances or inhibit their ability to live a dignified life.[34]

"I get really cold, but I cannot afford to turn the heating on and if we ever do turn the heating on, I clock watch, you know, it's on for 30 minutes and then it's off. I'll sit there suffering from chronic pain, with my legs going stone cold and my back killing me."

- Health benefits: People exposed to the cold and/or who are cutting back on essential expenditures (e.g., washing, bathing, cooking, using medical or mobility equipment) are likely to suffer health-related impacts, such as:

- high blood pressure

- increased risk of respiratory illness such as flu or common cold

- increased risks of heart attacks and strokes

- pneumonia

- increased pain

- exacerbation of pre-existing medical conditions (such as asthma, mental health issues, arthritis and chemotherapy-related cold sensitivity)

- mental health impacts resulting from these physical health impacts, increases in energy debt or other related debts and stress around affording energy bills[35].

- Preventing hospital admissions and excess winter deaths: There is a strong evidence base that improved thermal efficiency of the housing stock would reduce excess winter deaths, along with preventable cold-related hospital admissions[36][37]. For example, a rapid health impact assessment for Public Health Scotland found that the health consequences of fuel poverty and cold homes were well recognised with ‘higher mortality, morbidity and worse mental health all likely’[38]. Fuel poverty and cold homes also contribute to excess winter mortality. Across the UK, the NHS spends up to £856 million treating illness related to conditions potentially made worse by living in cold environments.[39]

"We need to look at what's the cost of not supporting it because we're talking about exacerbating impairments, we're talking about more GP time, more NHS time. We shouldn't be looking at it purely from a financial view but there's a big, big argument about how much money we could save by supporting people to live comfortably.”

- Markets could deliver more for consumers: targeted energy bill support could prevent energy debt accruing (which our Energy Affordability Tracker highlighted is particularly prevalent amongst those limited a lot by disability) or self-disconnecting from energy supplies. Research by Ofgem and Citizens Advice (2024) found that fear and anxiety related to debt meant some consumers put off addressing debt for longer[40]. Therefore, reduced anxiety and financial hardship may also encourage people to engage with their energy supplier.

- Employment and education access: Living in fuel poverty can create inequalities and barriers to access education and employment.[41][42] It is likely that energy affordability challenges may intersect with wider structural barriers for disabled people around both employment and education.[43][44] A wider benefit of ensuring disabled people have access to sufficient energy for basic, but often overlooked, needs is improved access to employment and education. Examples of this are: the ability to maintain sufficient charge on mobility equipment for work and leisure or, making the conditions for home working as a reasonable adjustment affordable and feasible.

14% of households with a disability or health condition in household reported being in energy debt or arrears. (Consumer Scotland (2024) Insights from latest Energy Affordability Tracker: Causes and impact of energy debt)

The existing landscape for energy affordability support is complex and may benefit from simplification and better targeting

Across both a GB and Scottish context, there are multiple schemes designed to improve the affordability of energy for different consumers (see table 1 on page 22). There is a risk that these arrangements may be confusing for consumers to navigate and may not lead to the most effective and efficient use of funding.

Participants in our research expressed concern that the current landscape for energy affordability support is very complicated. Consumer Scotland’s Energy Affordability Tracker shows varying levels of awareness of different support schemes. In workshop 2, participants highlighted that it can be overwhelming for the consumer to have to submit multiple applications for different pots of money, as well as needing to be aware of the different schemes to apply to.

Consumer Scotland’s policy paper on wider energy affordability policy recommended that governments and Ofgem should undertake a holistic review of existing support interventions[45]. This would provide an opportunity to ensure that available funding delivers maximum impact for improving affordability and improving consumer outcomes. Such work should include a review of how all the different Scottish fuel poverty and energy-related benefits could be better aligned or consolidated.

Potential consolidation or redesign of schemes is challenged by variations in the devolution of certain benefits. There are complexities working between the devolution of certain fuel poverty or energy affordability benefits (e.g., Winter Fuel Payment and Cold Weather Payment) and differences in scheme administration (Warm Home Discount). This would need consideration in the development of any future proposals around more effective targeting of existing funding.

Data matching and availability is the biggest barrier to effective support

There are numerous barriers to data-matching which create issues for the design of energy affordability support in GB, including in Scotland. While data sets can provide useful indications of certain characteristics of consumers (such as income), there are likely to be limited in their nature and unlikely to provide granular understanding of energy consumption, tariff structures or impact on expenditure amongst different consumers.

A range of practical challenges currently hinder more sophisticated targeting based on consumers’ needs:

- Usage patterns: lack of data to evidence different consumers usage patterns related to increased energy expenditure may mean it is more difficult to tailor support. Regarding medical equipment, data might be lacking, patchy or not held by a central agency regarding medical equipment which makes it difficult to access reliable and comprehensive data.

- Technology use: There is limited understanding across the energy sector of how disabled individuals use technology (such as smart meters) which may make the development of inclusive interventions more challenging. Citizens’ Advice (2023) undertook research to examine how flexibility (and related smart-related technology) might be more inclusive to consumers who are currently more likely to be excluded from the benefits[46]. Inclusive design could help to design future tariffs inclusively, such as time or type of use tariffs.

- Socio-economic factors: gaps in data which link income status of disabled people can mean there is no easy way to link income data with disability data, beyond passported benefits.

Targeting based on disability benefits

Addressing the above gaps requires targeted research and collaboration with disability advocacy groups to ensure that energy affordability interventions are inclusive and effective. However, many data gaps are likely to be enduring and, therefore, there would be merit in further consideration being given to ‘practical proxies’ to help identify those who should receive support. Long-term, there may be scope to explore whether there are existing datasets that can be made more widely available, or new datasets created, which may overcome some of these challenges. Additionally, where Scottish benefits data is used, there could be challenges regarding data sharing from Social Security Scotland which have not yet been fully explored.

There are specific challenges to designing energy support for disabled people in a Scottish context. The biggest challenge is the lack of available data to identify eligible people. Considering disability benefits alone, the options are more straightforward: Adult Disability Payment (working age), Child Disability Payment (under 16) and Attendance Allowance (over pension age).However, payment of this benefit does not take into account income.

Low income benefits are already included in the eligibility criteria for various energy affordability interventions and are likely to exclude many low income disabled people who are not in receipt passport benefits. This is further complicated by the fact that higher essential energy usage may be the primary driver of energy affordability challenges for disabled people. Therefore, the profile of a disabled consumer who may be in need of affordability support is different to that of a low income consumer.

With certain energy affordability options, such as the creation of a social tariff, the devolution of specific benefits (ADP/CDP) may also create challenges for designing a social tariff at GB level. If a future social tariff were to follow the design of Warm Home Discount, then broadening eligibility to include disabled people at a GB level will add complications to an already problematic scheme design.

Maintaining the current approach would involve data matching DWP benefits (such as Universal Credit) at a UK level and disability benefits at a Scotland level. Annex 1 provides more detail on both matched data and number of eligible consumers, where possible. This may also incur additional data sharing agreements between Social Security Scotland and energy suppliers or management of data through a third-party. In Scotland, redesign of the scheme to enable automatic data matching then data matching against energy expenditure will be complicated by multilevel administrations and existing data sharing regulations.

|

“It would be good to have a better tie up […] When someone is diagnosed with a particular illness, there should be an automatic route to ‘this is how you get help” – workshop 1 participant |

7. Policy options analysis

Exploring options

During both workshops with disabled people and their representative organisations, participants were asked to propose a range of potential policy options in response to the objective to provide targeted energy support to disabled consumers.

The options fell into the three distinct categories:

- Additional support based on social security status: Some suggestions focussed on expanding the eligibility of existing energy support schemes – such as the Warm Home Discount, Winter Fuel Payment or Child Winter Heating Assistance – to include disabled adults more explicitly. In essence, the suggestions involve expanding support to those in receipt of social security payments targeted at disabled people.

- Additional support based on health status: Some suggestions were to base eligibility not on social security status, but more narrowly on health criteria. These policies included the Warm Home Prescription – where people who struggle to afford energy and have health conditions made worse by cold can be ‘prescribed’ energy support by a health professional – and also an option to target support specifically at those who are terminally ill.

- Broader reforms: a range of broader support and reforms, potentially including interventions to improve energy efficiency, broader market reforms, and improved advice and signposting.

In addition to these categories of options, participants also considered the potential to introduce an energy social tariff. Whilst this option was in principle viewed very positively by participants, it was not possible to scope the design of a social tariff in detail as part of this work.

Participants considered the benefits and challenges to each of the policy options in an online workshop. Options were developed from the initial in-person workshop and limited to options which related to the findings of the workshop.

Table 3 summarises the key features and advantages and disadvantages of the identified policies. In the rest of this chapter, we elucidate those policy suggestions in further detail. Before that however, we set out the broader principles that the participants in our workshops identified to guide how the design of targeted energy support for disabled people should be approached.

Figure 1 (below) shows the longlist of potential interventions which workshop participant identified may improve affordability options for disabled consumers.

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows an overview of all interventions either suggested during workshop one (with disabled people and organisations) or in response to their input

Key features for designing targeted energy support for disabled consumers

Following our workshops, participants identified several features which should targeted energy support for disabled consumers:

- Compassionate, person-centred approach: there was a desire to see targeting which was done with kindness and ensuring it does not feel like an unwelcoming process.

"The benefits system makes you feel like you're not supposed to receive something so people are worried that if they get something they might have to pay it back and get into more financial trouble. A lot of people say that they don't have the time or the energy to fight for what they're entitled to."

- Reduce onus on consumer, ideally through automatic qualification and receipt of support: for example, by simplifying application processes. This would involve a transition towards either (a) a referrals-based approach in line with the ‘tell us once’ principle; or, more likely, (b) an automatic process which would reduce the onus on consumers of having to manually apply for support. Automatic, rather than applications-based, support relies heavily on data-matching. For example, Warm Home Discount in England and Wales matches Valuation Office Agency data on property characteristics is matched with data from the Department for Work and Pensions on the benefit receipt of households to identify households most in need of energy support; and this is then shared with energy suppliers who provide energy bill rebates to identified customers

- Trusted intermediaries are essential for linking consumers in vulnerable circumstances with support but participants also raised concerned about healthcare workers determining who can receive support without welfare training, or where relationships may already be strained: feedback from disability organisations at the workshops suggested that gatekeepers can result in a more difficult journey for disabled people. A gatekeeper is a person that controls access to something (e.g., a benefit). Trusted intermediaries are essential for linking consumers in vulnerable circumstances with support. There is also an extent to which assessment professionals are needed to ensure support is reaching those who need it. In an example given in the workshop, a healthcare professional could be perceived as a gatekeeper if they decide who can or cannot access support. The concern raised in the workshop focussed on the impact of ‘gatekeepers’ without sufficient welfare training or where the relationship may already be strained.

- Frontloaded support: one commonly reported problem with existing support is that it is often delivered later than consumers need it. For example, some energy suppliers issue the Warm Home Discount rebate to customers as late as March[47], which is after the peak winter period for high heating expenditure. This is especially challenging for prepayment meter users for whom it is less straightforward to smooth out seasonal spikes across the year.

- Tapered/stepped support (no cliff edges): a cliff edge is where a slight increase in income may result in loss of access to specific benefits/support such as energy bill support. Different eligibility criteria according to need would allow for ‘tapering’ of support: providing different levels of support in line with different requirements. However, effective tapering of support is difficult to implement due to data gaps.

Initial analysis of the various policy options suggests that no individual policy can perfectly meet all these features simultaneously. Some of the features are clearly in tension, such as requirements for ‘personalisation’ alongside the aspiration to be ‘automatic.’ However, the aspirational principles act as a useful framework for considering the relative merits of the various policy options subsequently discussed by participants.

Targeting on the basis of existing social security receipt provides broad but not very well targeted support

One set of options discussed by participants in our workshop were policies to provide additional energy bill support to people who are in receipt of disability payments, but who do not currently receive any support with their energy bills. The specific potential policies identified were:

- Making the Winter Fuel Payment available to working aged people in receipt of disability benefits

- Extending eligibility criteria for the Warm Home Discount to explicitly include consumers who are in receipt of a disability benefit

- Extending the Child Winter Heating Payment to working age adults with a disability.

The advantage of these policies is that the payments could take advantage of existing infrastructure, namely the existing disability payments in the social security system – with these existing payments becoming the qualifying criteria for the extended energy support. We have provided a breakdown of size of eligible groups in Annex 1. In principle it would be possible for these existing disability payments to ‘passport’ recipients directly to any extended energy support schemes. As such, these policies could score quite well on the identified criteria in relation to being automatic, without additional onus on recipients and without need for additional or separate assessment.

A disadvantage is that these schemes would potentially be targeted fairly widely, and hence be costly to deliver. There are currently around 430,000 adults in Scotland in receipt of either the Personal Independence Payment, or its replacement Adult Disability Payment.[48] Extending the Winter Fuel Payment to all of these individuals would cost around £65 million; and these costs would be higher still by around £15 million if Winter Fuel Payment was extended to the 150,000 adults above the State Pension Age who are in receipt of the Pension Age Disability Payment (the replacement for Attendance Allowance in Scotland).[49] However, financial savings may be made in prevention of cold-related (or power-related medical dependencies) hospitalisation and impact on healthcare costs. Therefore, a cost benefit analysis may strengthen the case for a higher cost intervention such as:

- Extending the Warm Home Discount to explicitly include disability as a qualifying criteria would have similar implications to Winter Fuel Payment in terms of eligible numbers and costs (the costs of extending the Warm Home Discount would be somewhat lower than the costs of extending the Winter Fuel Payment, since some working age households with a disability already receive Warm Home Discount. However, the number of disabled households already in receipt of Warm Home Discount is likely to be fairly small – a few tens of thousands – in the context of the numbers of additional recipients who might be brought into eligibility.

- Extending the Child Winter Heating Payment to adults would affect the 430,000 working age adults in receipt of disability payments, and if paid at the same rates as the Child Payment would be associated with costs of over £100 million.

A detailed assessment would be required as to whether providing energy support to all disabled people at equivalent rates would achieve an appropriate level of effective targeting, given the very different personal circumstances and experiences of consumers in this group and what this might mean in terms of their essential energy needs. Further research on the essential energy needs associated with different health conditions would be required to support an intervention of this type, to ensure that support was appropriately targeted.

Determining energy support on the basis of high expenditure provides scope to better target energy support

The workshops considered using health conditions more explicitly to target energy support. One way of doing this would be for the NHS to have the ability to prescribe heating support to individuals who struggle to afford energy and have health conditions made worse by cold. Another route to achieving this would be for specific funding to be available for consumers for medical equipment which relies on power provided by NHS or government.

The advantage of this policy is that it may enable provision of more tailored support to those who need it most – in this respect scoring well in relation to criteria around personalisation. However, there is a risk that such an approach would ‘medicalise disability’ by focusing on ‘counting the costs’ of individual impairments. Some research participants regarded such an approach as problematic and not in-keeping with the social model of disability.

Furthermore, there would clearly not be a straightforward route to this type of support being provided on an ‘automatic’ basis and recipients would implicitly be required to go through an additional ‘assessment’ with a health professional, who might therefore be perceived as a ‘gatekeeper.’

Further details are discussed in Table 2. The costs of such a scheme are difficult to forecast since it would depend on health professionals’ determination of need, and any guidelines around the use of the policy.

There is potential to target support to people who are terminally ill

There is a case for additional energy support for people who are terminally ill because of the increased energy costs experienced living with terminal illness. Energy support could either be a bespoke intervention for those who are terminally ill, or there may be opportunities to adapt eligibility criteria for existing affordability interventions to better target those with a terminal illness. Research by Marie Curie has showed that terminally ill people’s bills can rise by as much as 75% after diagnosis with a terminal illness due to additional essential energy use[50]. A proportion of this energy use is likely to be classed as medical dependency (e.g., hospice beds, ventilators, feeding pumps, nebulisers and oxygen saturation monitors)[51].

Although participants in workshop 2 did not want to identify particular groups of disabled people who would be deemed more ‘in need’ of support, there was consensus that people who are terminally ill should be prioritised. There could be an opportunity to use Benefits Assessment for Special Rules in Scotland (BASRiS) eligibility to identify those who are terminally ill. BASRiS is a form to support Adult Disability Payment and Child Disability Payment[52]. Attendance Allowance is reserved and comes under an SR1 form for special rules although planned devolution next year could provide the opportunity to include those over pension age[53]. The form must be supported by the clinical judgement of registered medical practitioners or nurse.

Proportionately, the eligible group form a much smaller group of recipients than any broader targeted energy support. Therefore, an additional scheme for terminally ill children and adults may be a more achievable policy for the Scottish Government.

Specifically, data indicates that in summer 2024 there were some 6,200 adults and 155 children in Scotland who had a terminal illness under BARSiS eligibility.[54] The cost of any such energy affordability scheme to support this group would thus depend on its value. If for example the policy provided support equivalent to 20% of a typical energy bill (i.e. £500 annually), then the total cost would be just over £3 million. If the policy provided support worth 50% of a typical bill (typical bill at £1,568 so approx. £1,250[55]), the total cost would be in the region of £8 million.

The feasibility of a scheme offered by Scottish Government is particularly enabled by the devolution of Adult Disability Payment and Child Disability Payment. Given that some adults already receiving Adult Disability Payment and Child Disability Payment may become terminally ill, a further referrals process would be required. However, Attendance Allowance (using the SR1 form for special rules) would require discussions and data sharing with Department of Work and Pensions who administer it, adding complexity. Pension Age Disability Payment will eventually replace Attendance Allowance and is being piloted in Scotland, with a Scotland-wide rollout planned from 2025. Therefore, there is an opportunity for more straightforward targeting to those over pension age after the devolution of Pension Age Disability Payment[56].

The following section shows benefits and challenges of each policy option, primarily informed by participants in workshop 2

Policy option 1: Expansion of Warm Home Discount to disabled people by widening eligibility criteria to include disabled consumers. Funded through levy on energy bills. £150 flat rate discount

Amount:

- £150 per household

Cost:

- Up to £65 million

Benefits:

- Expansion of Warm Home Discount uses existing infrastructure

- Likely to be pre-existing consumer awareness of the measures

- May be possible to use existing data to passport eligible benefits to save people from having to apply

Challenges:

- Application-based nature means it is not accessed by all who need it

- In Scotland, consumers may miss the deadline for applications

- Warm Home Discount in Scotland would likely need a significant redesign to meet criteria for support

- Increases to eligibility will result in higher bills for all consumers

Policy option 2: Expansion of Winter Fuel Payment by widening eligibility to include disabled consumers. £200-£300 towards fuel bills for adults over 66 on Pension Credit or other eligible benefits. In process of devolution but has been paused after policy changes.

Amount:

- £200-300 per person

Cost:

- Up to around £80 million

Benefits:

- Expansion of Winter Fuel Payments makes use of existing infrastructure

- Likely to be pre-existing consumer awareness of measure

- May be possible to passport benefits to make process automatic

Challenges:

- Changes to Winter Fuel Payment by UKG may prevent viability of expansion to include additional consumers

Policy option 3: Expansion of Child Winter Heating Assistance to disabled adults. £235.70 payment to household with eligible disabled people

Amount:

- £235.70

Cost:

- Up to around £110 million

Benefits:

- General support for NHS contribution to medical equipment

- Current focus on electrical equipment contribution may be too narrow so there is a clear case for expansion to different additional types of medical and mobility equipment

Challenges:

- Data gaps on medical equipment by NHS or private purchase

- Rebates would need to be upfront rather than in arrears to have the most benefit

- Uncertainty about NHS’s current capacity to deliver this due to fiscal constraints

Policy option 4: Warm Home Prescription. Trialled across England and Scotland to help people who struggle to afford energy and have health conditions made worse by cold. Offered warm home prescription

Amount:

- Variable

Cost:

- N/A

Benefits:

- Energy Systems Catapult have undertaken successful pilots on this policy option

- Offers potential for tailored intervention based on individual need

- Health is devolved so there may be an opportunity to advocate for and design a Warm Home Prescription at a Scottish level

- Successfully trialled with positive feedback and outcomes[57]

- Warm Home Prescription contributes to other targets such as the Scottish Governments 3 missions (from workshops participants)[58]

- May be scope to coordinate with Home Energy Scotland to expand the scheme

- Since the workshop, ESC had announced it is teaming up with Scottish Power to expand and deliver WHP

Challenges:

- If scaled up from current pilot areas, the scheme would need to applied consistently and with an appeals process

- Uncertainties on funding for a scaled up scheme

- Not clear what the best funding mechanisms would be or whether it is scalable to a universal level

Policy option 5: Targeted energy support for those living with terminal illness. NB: this policy option was developed after workshop 2 and in response to input and wider engagement.

Amount:

- To be determined. Indicatively £500 per annum

Cost:

- Approx £3million (based on assumption of support equivalent to £500 per annum)

Benefits:

- There are a much smaller number of people claiming under special rules which would mean there is scope to create a smaller, targeted scheme

- Participants felt that those who were terminally ill or end-of-life were an important group to prioritise for energy-related support

- ADP/PIP claimed under Special Rules could be a clear route to reach those who are eligible and distributed through Social Security Scotland

Challenges:

- Difficult to capture those who are already on ADP/PIP and are later diagnosed with terminal illness. A secondary referrals process would be needed.

Policy option 6: Energy 'social tariff'. Flat rate or unit rate discount. Funded through energy bills or taxation

Amount:

- Unknown

Cost:

- Unknown

Benefits:

- Could take into account volumetric usage through unit cost discount

- Especially if social tariff were targeted a low income, a unit rate discount would link to energy usage

- Less vulnerable to change if it is raised through bills

- Easier for consumers to access compared to some measures

- Represent a positive change to how the energy market works

Challenges:

- There has not been clarity about whether it forms UK Government priorities (noting that the workshop was conducted under the previous Conservative government).

- Likely to increase bills for other consumers including some disabled people who may fall just outside eligibility

- Fairness and proportionality issue in wider market

- Risk of cliff edges for those who are not eligible but in need

- Challenging to put system in place unless use existing schemes such as Warm Home Discount

- Expensive when combining low income and disabled consumers

- Discount on bills prioritises subsidising consumption rather than incentivising energy efficiency

There are opportunities for intervention in the broader energy market to improve outcomes for disabled consumers

Beyond targeted energy support, there is an additional need to consider how disability and health conditions can be considered within the broader landscape of potential interventions across the energy market. Consumer Scotland has identified the following additional areas where consideration of this issue will be required:

- Energy efficiency and low carbon technology: energy efficiency improvements are critical to disabled people having access to safe and healthy temperature at home in the longer term[lix]. Warm Home Prescription provides a direct payment (in the first instance) and later access to energy efficiency support once people are engaged. Warm Home Prescription and previous schemes, such as the Warm Home Oldham scheme, have illustrated the potential for energy efficiency upgrades focussed, in part, on the disability or health status of consumers[lx].

Additionally, there may be a role for access to battery storage and solar technologies for people who are reliant on medical equipment to reduce their bills through either (1) using solar power (when available) and battery storage or (2) using battery storage to allow those with medical equipment to benefit from flexible tariffs (see point 2 below). This may also improve resilience of households with disabled people during emergency situations[lxi]. However, there is a research gap on the use of battery storage and solar for those dependent on medical equipment.

Key enablers of improving access to energy efficiency interventions and low carbon technology for disabled people include:

- reinstating Personal Independence Payment (and Adult Independence Payment) as eligibility criteria for Energy Company Obligation funding

- improving signposting to Home Energy Scotland from Social Security Scotland

- An inclusive energy market design: Inclusive design of essential-for-life services such as energy means designing markets in such a way that all consumers can access services which work for them[lxii]. Existing retail energy market design is unlikely to result in a fair and inclusive energy market for future consumers, or to support the widespread changes needed to enable the transition to Net Zero.[lxiii] For the benefits of a decarbonised energy system to be shared fairly with consumers, innovative approaches are likely to be required to ensure all consumers have fair access to the benefits of opportunities such as savings from low carbon technologies and flexibility.[lxiv][lxv] Fair by Design have undertaken work in using inclusive design to model a fair transition to net zero[lxvi] and provide an example of how the future energy market may be inclusively designed.

- Innovative design of products and services for energy for disabled people: there are opportunities for the energy industry to innovatively design products and services that specifically meet the needs of disabled people and those with health conditions. With the right incentives for suppliers, technology providers and networks, there may be an unexplored market for products and services which are specifically designed for disabled people (such as battery/solar as explored above). Unlocking this market may produce co-benefits in the design of services which are more affordable and tailored to disabled consumers and their diverse needs.

- Ethnographic and person-centric research to understand how different disabled people use energy in the home (inclusive of transport): there are still large evidence gaps in terms of how disabled people, and those with health conditions, use energy in the home (and transport, particularly around EV charging). Future research should focus on deepening understanding of how different disabled consumers use energy in the home. Ethnographic or living lab approaches would avoid medicalising disabled people and ‘counting’ their energy costs but rather gain a richer and more person-centred evidence base from which to design future energy policy and regulation. There may be a role of UK and Scottish governments or Ofgem in funding research which provides an ethnographic lens to energy use and expenditure.

- Advice sector and signposting: there are opportunities for the existing landscape to improve the support for disabled consumers. Within workshop 1, participants discussed the possibility of a Warm Referrals Network which improves signposting for disabled people:

‘I feel like a warm referrals network between organisations, where you’re not expecting individuals to go to all of the different places but instead the local organisations get together to say ‘who are these people that we are constantly seeing in our services?’ and actually deal with the underlying issues.’

Further ideas put forward to improve the advice landscape are shown in figure 1 and include understanding barriers to accessing financial support, better signposting and improved understanding of disabled consumers’ journeys to create best practice.

8. Conclusion

There is an urgent need for more targeted and expanded support for disabled individuals with high essential energy expenditure. Access to affordable energy is crucial for maintaining the health, dignity, and wellbeing of disabled people and those with health conditions. In turn, improvements in energy affordability could help to prevent hospital admissions resulting financial impacts on health services. However, current energy affordability policies, including emerging proposals for a future social tariff, have not adequately addressed the needs of those who require higher energy usage due to their health conditions, leaving consumers in this situation vulnerable to increased hardship.

To address this gap, energy support schemes need to be better designed to meet the specific needs of disabled consumers who rely on higher volumes of energy. While a new social tariff was the most favoured policy solution identified by participants in the workshops, there was also notable support for rebates for medical equipment. Data availability and matching remain significant challenges in implementing such targeted support, though creating a data infrastructure for this purpose could be a valuable long-term solution.

Without active inclusion of the needs and requirements of disabled people, energy pricing policies risk exacerbating inequality and further marginalizing a vulnerable group of consumers. The social model is crucial in ensuring that both current and future energy markets take into account the specific needs of disabled people and those with health conditions. An energy market that overlooks these needs risks further entrenching disadvantage and missing opportunities to improve outcomes for disabled consumers.[lxvii] Embedding the lived experience and expertise of disabled people is critical to ensuring the principle of ‘nothing about us without us. By incorporating these perspectives, energy policy can more effectively reflect the diverse experiences of disabled individuals and address the barriers they face, leading to a more inclusive and equitable energy market.

9. Recommendations

To address the challenges for consumers set out in this report, Consumer Scotland recommends:

1. The Scottish and UK governments and Ofgem should clearly recognise in relevant policy documents and activities, the significance of ‘high essential energy expenditure’ as an important driver of energy affordability challenges for disabled consumers. For disabled people, this is primarily related to those essential for health and wellbeing needs which are additional to those of a non-disabled consumer.

Recognition of this affordability driver should be applied to consideration of any reform to existing market structures (e.g., standing charges or levy rebalancing) and to future market design (i.e., changes needed for increased electrification and development of a future social tariff).

2. The Scottish and UK Government should undertake a holistic review of existing energy affordability interventions and examine the options for developing interventions which are targeted at disabled people and those with health conditions who have higher essential energy needs. This could be done through:

- Better targeting of existing fuel poverty and energy affordability schemes to include disabled people (for example, Winter Fuel Payment) AND

- Inclusion of disabled people within the design of future targeted energy affordability support

3. The Scottish Government should consider opportunities to provide additional energy affordability support targeted at those who are terminally ill. This may be primarily based on those receiving Personal Independence Payment/Adult Disability Payment[3] under the Special Rules for Terminal Illness (i.e., SR-1 or BASRIS)[4]. There may be options to design this support to specifically reach those who are end-of-life via Adult Disability Payment.

4. A cross-industry approach, (e.g., UK and Scottish governments, regulator, energy suppliers and networks) to proactively consider how disabled consumers’ needs may be better met in the energy market (including areas such as energy efficiency and low carbon technology). This includes increased access to energy efficiency and low carbon technology (See figure 1 on page 32 for overview of policy suggestions from the workshops).

10. Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Table 1 shows a breakdown of possible data sources and, where possible, the number of people who would be eligible.

|

Type of data

|

Data source |

Number of people |

|

Government databases |

Adult Disability Payment/Personal Independence Payment (higher rate only – either/both daily living/mobility)** |

At least 182,635 (likely under-representative due to transition from PIP to ADP) |

|

Adult Disability Payment (all) (and PIP transfer) |

Approx. 440,791[5] |

|

|

Adult Disability Payment under the Special Rules for Terminal Illness (i.e., SR-1 or BASRIS) |

||

|

Child Disability Payment |

84,750[lxix] |

|

|

Child Disability Payment under BASRiS[lxx] |

155[7] |

|

|

Attendance Allowance[lxxi] |

||

|

Attendance Allowance (Higher rate) |

91,912 |

|

|

Attendance Allowance where main disabling condition is terminally ill[lxxiii] |

4,185 |

|

|

Government/social security data sets |

UC or other income data[lxxiv] |

519,010 |

|

Data-matched |

UC or other income data combined with those receiving a disability benefit CDP, ADP and Attendance Allowance (and transitional benefits) |

Not possible due to devolution (transition) of benefit |

|

|

UC or other income data combined with those receiving adult disability benefits ADP or AA |

Not possible due to devolution (transition) of benefit |

|

|

UC combined with all receiving ADP |

Not possible due to devolution (transition) of benefit |

|

|

UC combined with those receiving a higher rate component of ADP |

Not possible due to devolution (transition) of benefit |

|

|

HMRC data on households earning under £20,000 and £40,000 (?) combined with those receiving a disability benefit CDP, ADP and Attendance Allowance |

Not possible due to data gaps |

|

|

HMRC data on households earning under £20,000 and £40,000 those receiving adult disability benefits ADP or AA |

Not possible due to data gaps |

|

|

receiving adult disability benefits ADP or AA |

Not possible due to data gaps |

|

|

all receiving ADP |

Not possible due to data gaps |

11. Endnotes

[*] Note, Scottish Government only has powers over Adult Disability Payment. PIP is referenced in relation to the transfer for PIP recipients to ADP.

[†] BASRiS stands for Benefits Assessment for Special Rules in Scotland, and is a form that can be used by terminally ill people to claim fast-tracked disability benefits under the Special Rules for Terminal Illness (SRTI). SRTI use a clinical judgement definition of terminal illness whereby a doctor or a nurse can declare someone is terminally ill without having to project how long they have to live.

[3] Note, Scottish Government only has powers over Adult Disability Payment. PIP is referenced in relation to the transfer for PIP recipients to ADP.

[4] BASRiS stands for Benefits Assessment for Special Rules in Scotland, and is a form that can be used by terminally ill people to claim fast-tracked disability benefits under the Special Rules for Terminal Illness (SRTI). SRTI use a clinical judgement definition of terminal illness whereby a doctor or a nurse can declare someone is terminally ill without having to project how long they have to live.

[5] Note, due to ongoing transition from Personal Independence Payment to Adult Disability Payment, figure has been calculated by adding July 2024 ADP total payments to PIP total payments for Scotland. Therefore, there may not be complete accuracy in the figure.

[6] As of July 2024

[7] As of June 2024

[8] As of February 2024 (most recent figure)

[1] Regen (2022) Why are disabled people more vulnerable to rising energy costs and what should be done about it?

[2] Gillard et al. (2017) Advancing an energy justice perspective of fuel poverty: Household vulnerability and domestic retrofit policy in the United Kingdom

[3] Scope (2023) Energy and cost of living crisis

[4] Consumer Scotland (2024) Disabled Consumers and Energy Cost – Interim findings

[5] UK Power Networks (n.d) Extra support for people reliant on electricity for medical reasons

[6] Griffiths (2020) Disability, In Ellison et al. (Eds) Handbook on Society and Social Policy Elgar (p. 123)

[7] Consumer Scotland (2024) Energy Affordability Policy

[8] Ofgem (2024) Consumer vulnerability strategy refresh

[9] NEA/Fair by Design (2022) Solving the cost of living crisis

[10] UCL/Aldersgate Group (2023) The Case for a Social Tariff: Reducing Bills and Emissions, and Delivering for the Fuel Poor

[11] Resolution Foundation (2022) A chilling crisis

[12] SMF (2023) Bare necessities: Towards an improved framework for social tariffs in the UK

[13] New Economics Foundation (2023) The National Energy Guarantee

[14] NEA/Fair by Design (2022) Solving the cost of living crisis

[15] UCL/Aldersgate Group (2023) The Case for a Social Tariff: Reducing Bills and Emissions, and Delivering for the Fuel Poor

[16] Resolution Foundation (2022) A chilling crisis

[17] SMF (2023) Bare necessities: Towards an improved framework for social tariffs in the UK

[18] New Economics Foundation (2023) The National Energy Guarantee

[20] Consumer Scotland (2024) Energy Affordability Policy - October 2024

[21] Scope (2023) The social model of disability for businesses

[22] Social model of disability | Disability charity Scope UK

[23] Griffiths (2020) Disability, In Ellison et al. (Eds) Handbook on Society and Social Policy Elgar (p. 123)

[24] Griffiths (2020) Disability, In Ellison et al. (Eds) Handbook on Society and Social Policy Elgar (p. 123)

[25] Consumer Scotland (2023) Scottish Energy Insights Coordination group: report to Scottish Government

[26] Consumer Scotland (2024) Disabled Consumers and Energy Cost – Interim findings