1. Our Response

Key Recommendation

The Government should not move the cost of the Warm Home Discount from the standing charge to the unit rate. Any changes to how costs are passed through to consumers should be considered in a holistic manner as part of Ofgem’s Cost Allocation and Recovery Review. This will ensure all costs are passed through to consumers efficiently and fairly.

Summary

Consumer Scotland welcomes the opportunity to respond to the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero’s (DESNZ) consultation on Warm Home Discount (WHD) cost recovery. We acknowledge the Government’s commitment to supporting low-income households with their energy costs and the need for appropriate bill structures.

Consumer Scotland recommends that DESNZ does not proceed with the measure set out in its consultation. The change would force households with higher energy use to bear more of the cost of the WHD, increasing their bills. It is unclear what justification there is for this.

While there is some correlation between higher energy use and financial means, it is not universal. Many less well-off households have unavoidably high energy use. This includes the terminally ill, those with essential medical equipment in their homes, the elderly or those with young children, or those living in poorly insulated homes. Many of these households would be worse off as a result of the change proposed.

Consumer Scotland acknowledges consumer’s legitimate concerns about standing charges, especially electricity standing charges. However, we believe piecemeal reforms to address these concerns risks unintended consequences for the very consumers that the WHD is designed to protect.

We would prefer a more rounded approach to be taken to reforms to bill structures. Ofgem have already kicked off their Cost Allocation and Recovery Review (CARR) which is looking at how all energy system, environmental and social scheme costs are passed through to consumers. This piece of the work is the best vehicle for considering changes like the one proposed here by DESNZ in a holistic way. In doing so, we can ensure that costs are passed through efficiently and fairly, and minimise the risk of creating unintended losers.

Question 1: Considering the impacts across all consumers, including impacts on protected groups, do you support moving WHD costs to the unit rate? (yes/no) Please explain your reasoning and provide any supporting evidence

No, we do not support moving WHD costs to the unit rate. The change proposed would mean that households with higher than median consumption would bear more of the cost of the WHD. And, in the event that suppliers have to be compensated for the additional risk of under-recovery from low users, it would mean that more than half of all households are worse off as a result of the change.

While there is some correlation between higher energy use and financial means, it is not universal. Many less well-off households have unavoidably high energy use. This includes the terminally ill, those with essential medical equipment in their homes, the elderly or those with young children, or those living in poorly insulated homes. Many of these households would be worse off as a result of the change proposed. By way of example, research by Marie Curie has found that a terminally ill person’s energy bill can rise by as much as 75% after their diagnosis. Instead of an individual paying £39 a year towards the WHD as at present, they could be paying £68 if DESNZ proceeds as proposed.

We acknowledge that many consumers hold a strong negative opinion of the standing charge. However, we know that once its rationale is explained the strength of negative feeling diminishes. Given the high risk of creating unintended losers out of this policy we would recommend a more comprehensive approach to reform is taken.

CARR as the appropriate vehicle for cost recovery reform

Consumer Scotland is concerned that the change proposed by DESNZ is a narrow, piecemeal one. It will likely create unintended losers, and there are no related proposals within the consultation for how to prevent this from happening.

Ofgem’s CARR, on the other hand, is explicitly designed to examine how system-wide costs, including policy costs like WHD, should be allocated and recovered across energy bills. By giving rounded consideration to the efficiency and fairness of all costs, there is the opportunity to avoid the type of unintended outcome set out above. This could include, for example, improving the link between financial means and energy use to ensure proportionate support for those that need it.

Consumer Scotland’s response to Ofgem’s CARR consultation set out our preferred process:

-

- Efficiency First: A bottom-up analysis of current cost allocation and identification of efficiency improvements;

- Outcomes-Based Adjustments: A top-down consideration of whether current or alternative allocation principles (such as ability-to-pay or fairness should be applied).

On policy costs like WHD, Consumer Scotland recommends that they are clearly identified and recovered in line with cost reflectivity principles. Firstly, this ensures both that different costs are recovered in the most efficient manner, benefitting what consumers ultimately pay on their bills. Secondly, this ensures transparency about which costs are fixed (and are appropriate for standing charges), and which are variable (and are appropriate for unit rates), and provides consumers with appropriate knowledge to react to price signals.

Ultimately, there is a risk of incoherent policy development between DESNZ and Ofgem should a decision be made on where WHD should sit before CARR concludes. If WHD costs are moved to unit rates before CARR concludes, Government will have made a judgment about policy cost recovery that CARR's final framework may contradict. This risks Ofgem having to revisit the issue or, conversely, anchoring bill structures around a decision made outside the comprehensive review process.

Obscuring Cost Drivers

A core principle of fair and transparent energy bills is cost reflectivity. Charges should reflect the nature of the underlying costs being recovered. Costs that vary with consumption (e.g., wholesale, distribution network usage) are arguably more efficiently recovered through unit rates, where consumers can vary their usage through unit rates. Costs that are fixed regardless of consumption (e.g., policy support schemes with a fixed recipient population) are more efficiently recovered through fixed charges like standing charges.

The Warm Home Discount is fundamentally a fixed policy cost. It is not based on how much energy eligible households consume. It is, currently, based on the number of households eligible for means-tested benefits in any given year in England and Wales, with Scotland receiving a proportional fixed percentage share of the overall WHD budget (adjusted each year). The cost per eligible household is determined by DESNZ (equating to £39 for the average dual fuel household according to this consultation).

Ofgem's consumer research on standing charges provides important evidence. Ofgem found that consumer sentiment toward standing charges improved when consumers were provided with information about what standing charges were for, how they were calculated, and presented with the trade-offs with other costs. This indicates that consumer concerns about standing charges are partly driven by a lack of understanding, and not by inherent unfairness in the mechanism itself.

Consumer Scotland recommends that rather than moving fixed costs to unit rates, that risks obscuring policy costs further, the Government and Ofgem should invest in consumer communication and energy literacy. Explaining what makes up standing charges, and which costs are fixed and which are variable, can strengthen understanding of billing structures.

Technical Risks in Cost Recovery Mechanism

The consultation proposes to recover the WHD through unit rates and to reconcile the actual spend against the forecast spend annually. This involves an adjustment to cost recovery should there be an under or over recovery from the previous price cap period.

There are clear risks to both consumers and suppliers if under recovery occurs, increasing the cost of energy over time. This is caused by the fixed cost of the WHD being recovered through a non-fixed cost recovery mechanism (unit rates). Suppliers may apply a risk premium to unit rates to minimise any shortfall and reduce their operational costs and protect margins, increasing the cost of energy for all consumers. A number of difficult external factors may introduce greater risks of under recovery, e.g. mild winters. This is a similar problem as seen in potential zero or low standing charge reforms discussed over the last 12 months, and highlights the structural risk that a volumetric recovery of a fixed policy cost may cause.

A specific concern arises for consumers on multi-rate tariffs (e.g. economy 7, 10, etc.). The consultation notes: “There is no way to mandate how suppliers allocate WHD across unit rates” within multi-rate tariff structures. The lack of ability to mandate how suppliers allocated WHD costs presents problems for multi-rate tariff consumers. There is a risk that supplier discretion, in an effort to protect their margins and manage under recovery risk, means that WHD costs could be further shifted between consumer groups on multi-rate tariffs. For example, if costs are solely allocated to peak usage unit rates, this may disadvantage particular groups (e.g. unavoidable high usage households, as discussed below) in unpredictable ways. There is a significantly higher number of Scottish households with restricted meters compared to the rest of Great Britain. Further, consumers in Scotland on multi-rate meters are often linked to electric heating, and many live in rural areas, both factors that make them more likely to be at risk of or in fuel poverty.

Consumer Scotland is concerned that this technical risk is underestimated in the consultation. While the proposals acknowledge the risk, it is unclear how consumers will not ultimately face higher unit rates above the recovery cost of the WHD. Further, Consumer Scotland does not think the proposals provide adequate consumer protection for consumers on multi-rate tariffs, many of whom suffer from fuel poverty and are meant to be the target of the WHD. Consumer Scotland recommends the Government consider these impacts to consumers further, and provides clear consideration for how multi-rate tariff consumers may be affected.

Assumptions on Higher Usage Households and Distributional Impacts

Consumer Scotland is concerned with assumptions made in the WHD consultation that moving to unit-rate recovery is more progressive because higher-consuming households (assumed to be wealthier) will pay more. Further, there is a risk that the minimal benefit for lower usage households may perversely benefit financially better off households that can avoid volumetric charges through the use of low carbon technology (LCT) such as solar and batteries, and lower income households who have been unable to make this investment are left paying higher unit rates to make up any WHD cost short-fall.

There are many reasons why high-consumption does not correlate in all cases with wealth or income, including high essential expenditure for households due to factors beyond their control, including:

-

- Electrically heated households often consumer significantly more energy than equivalent gas-heated households, as illustrated in the Scottish Housing Condition Survey 2023 found that 52% of households using electricity as their primary heating fuel were fuel poor, higher than households using gas (32%), and oil (26%).

- Medical equipment users require high consumption due to life-sustaining devices (oxygen concentrators, powered beds, dialysis machines, etc.)

- Rural and island households in Scotland have higher heating needs due to climate and lower energy efficiency, not necessarily wealth.

- Households with vulnerable members (e.g. young children, elderly, disabled people) who may need enhanced heating regimes.

Shifting additional costs in a way that may disproportionately affect these households raises fairness concerns, and affordability and debt risks. The challenges facing these households have been repeatedly reflected in Consumer Scotland’s Energy Affordability Tracker, finding that low-income households, those receiving means-tested benefits, and those with a long-term disability or health condition are most likely to report energy affordability challenges.

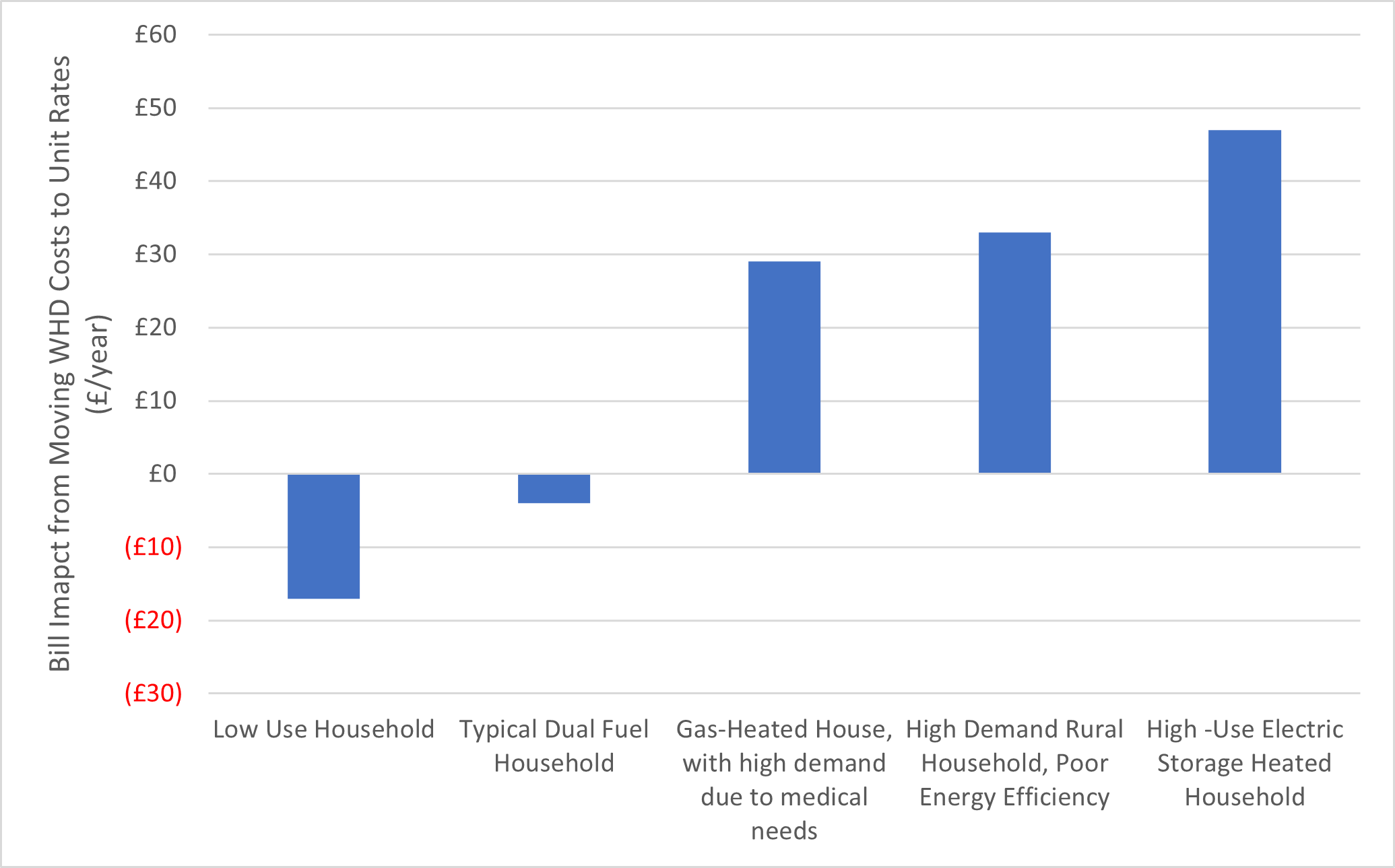

The consultation document makes an argument that some of these consumers will be better off overall due to energy bill measures announced at the UK Budget 2025. However, other policy proposals should not detract from the effect of this policy proposal. The analysis in the consultation highlights that these proposals will have a negative impact on all high essential or inflexible demand users archetypes included in the analysis, as illustrated in Table 2 of the consultation and in figure 1 below:

Figure 1 - Bill Impact from Moving WHD Costs to Unit Rates (£/year)

(DESNZ (2025), Consultation on Warm Home Discount (WHD) Cost Recovery, Table 2 – Illustrative Impacts of moving WHD costs to the unit rate on specific household archetypes in 2026/27 (nominal, inc. VAT))

While bill measures announced in the 2025 Budget are predicted to provide a net benefit to all households archetype analysed above, the WHD measures proposed in this consultation will still disproportionately affect higher essential usage and inflexible demand households, with minimal predicted benefit for low usage households (savings of £17 per year) and typical dual fuel households (savings of £4 per year).

Further, a low usage household may not necessarily be a household in a lower income bracket, but may instead have LCT resources, using solar PV and batteries to draw less from the energy grid. If high-income users with more LCT can sharply cut import costs and pay mainly the standing charge, those unable to invest in LCT (including many low-income consumers) are left paying higher bills via higher unit rates to make up the difference.

Again, there is a real risk that the Government’s current WHD proposals would benefit these potentially better-off households, putting more social policy costs on lower-income households that cannot otherwise avoid drawing energy from the grid.

Consumer Scotland disagrees with the Government’s proposals due to the disproportionate effect it will have on households least able to absorb additional costs. Higher-income households with solar and battery systems can reduce grid reliance and avoid much of the charge, while the fixed cost of WHD remains. This approach could therefore risk concentrating the burden on lower-income households and those least able to avoid higher essential expenditure. Such households can be in or near fuel poverty, undermining affordability and fairness and ultimately the aims of the WHD.

2. About us

Consumer Scotland is the statutory body for consumers in Scotland. Established by the Consumer Scotland Act 2020, we are accountable to the Scottish Parliament. The Act defines consumers as individuals and small businesses that purchase, use or receive in Scotland goods or services supplied by a business, profession, not for profit enterprise, or public body.

Our purpose is to improve outcomes for current and future consumers, and our strategic objectives are:

-

- to enhance understanding and awareness of consumer issues by strengthening the evidence base

- to serve the needs and aspirations of current and future consumers by inspiring and influencing the public, private and third sectors

- to enable the active participation of consumers in a fairer economy by improving access to information and support

Consumer Scotland uses data, research and analysis to inform our work on the key issues facing consumers in Scotland. In conjunction with that evidence base we seek a consumer perspective through the application of the consumer principles of access, choice, safety, information, fairness, representation, sustainability and redress.

3. Consumer Principles

The Consumer Principles are a set of principles developed by consumer organisations in the UK and overseas.

Consumer Scotland uses the Consumer Principles as a framework through which to analyse the evidence on markets and related issues from a consumer perspective.

The Consumer Principles are:

-

- Access: Can people get the goods or services they need or want?

- Choice: Is there any?

- Safety: Are the goods or services dangerous to health or welfare?

- Information: Is it available, accurate and useful?

- Fairness: Are some or all consumers unfairly discriminated against?

- Representation: Do consumers have a say in how goods or services are provided?

- Redress: If things go wrong, is there a system for making things right?

- Sustainability: Are consumers enabled to make sustainable choices?

Our response has been framed by our Consumer Principles. Reviewing policy against these principles enables the development of more consumer-focused policy and practice, and ultimately the delivery of better consumer outcomes.