1. Summary

Consumer Scotland welcomes this UK Government consultation on the non-domestic smart meter rollout. We broadly agree with the proposals set out and recognise this is a step-change in approach. We understand that mandating installations with a certain section of consumers could help accelerate progress and is an approach which has driven near 100% coverage in other countries such as Italy and Spain. However, attention must be given to the potential associated negative impacts and trade-offs, particularly for the smallest businesses and most vulnerable consumers. In developing this policy framework further, we would like to see an approach that:

-

- Better reflects the fact that some domestic consumers/households will be impacted as part of the non-domestic smart-meter rollout.

- Ensures small and microbusinesses that are struggling with persistently high energy costs and to negotiate fair and affordable energy contracts are provided adequate support and incentives around the installation of smart meters.

- Drives much-needed data improvements on the different groups of consumers impacted by the non-domestic smart meter rollout that can inform policy decision-making in this area and others going forward.

- Learns lessons from the domestic smart meter rollout and the phasing out of the Radio Teleswitch Service (RTS), including in targeting those living and/or doing business in rural and remote locations.

- Incorporates clear targets that measure contracts and installations in locations or amongst groups identified as hard-to-reach, and overall consumer experiences of the rollout.

- Coordinates with related policy areas and mechanisms including the regulation of Third-Party Intermediaries (TPI), the Maximum Resale Price (MRP) arrangements, reform of electricity pricing and grid and large-scale storage upgrades.

Non-domestic consumers have a significant role to play in achieving the potential 10-12 GW of consumer-led flexibility capacity that DESNZ and NESO project is possible by 2030 and essential to realising the clean power 2030 mission. [1] [2] If done right, the non-domestic smart meter rollout could help reduce bills and energy demand for small businesses, microbusinesses and domestic end-users of non-domestic contracts in Scotland and across the UK and boost economic growth. It can also help reduce constraint and network build needs, lowering all UK consumers’ energy bills.

Consumer-led demand flexibility is a key area of focus for Consumer Scotland’s energy work. We previously responded to the UK Government’s consultations on the smart metering policy framework post 2025 [3] and on Consumer-Led Flexibility. We also have new research on domestic consumer flexibility due to be published later in 2026.

2. Our response

Question 1. Do you agree with the proposed policy package with respect to non-domestic smart-contingent contracts set out in Section One? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

Overall, the proposed policy package appears reasonable, and the provision of universal implementation and communications requirements in relation to smart-contingent contracts alongside a legally binding code could improve outcomes for non-domestic consumers.

As set out in our response to the UK Government’s consultation on a smart metering policy framework post 2025, [4] the following principles are key and apply to both non-domestic and domestic smart meter rollouts, particularly where a more mandatory approach is to be adopted:

-

- Considering how best to target harder-to-serve and vulnerable consumers.

- Ensuring a high-quality customer journey to support consumer confidence.

- Setting regional targets and obligations.

With these principles in mind, we would raise the following challenges that need to be considered by DESNZ, the regulator Ofgem and other relevant stakeholders, in refining and implementing the non-domestic smart meter rollout proposals.

The impact of smart-contingent non-domestic contracts on domestic end-users

Consumer Scotland believes that these policy proposals will have an impact on households, despite the accompanying analytical evidence to the consultation documentation stating they will not. Indeed, elsewhere in the documentation, in relation to fairness and proportionality, DESNZ highlights that suppliers should “Pay particular attention to the needs & circumstances of…residents at non-domestic premises.” As of 2023 and according to Age UK and DESNZ figures, 900,000 households were on non-domestic contracts.[5] DESNZ has also previously estimated that between 375,000 and 450,000 households are resold electricity by an intermediary, which could potentially be on a non-domestic contract. Ofgem has highlighted that this figure is likely to be higher given data limitations.[6] Previous Ofgem research also found that some suppliers believed that the numbers of domestic consumers on non-domestic contracts would increase with developers and landlords choosing to build on-site renewables and consolidating demand.[7]

Domestic consumers on non-domestic contracts are already potentially at a disadvantage as they do not enjoy the same protections as those on domestic contracts. This includes the price cap, access to additional support such as the Priority Services Register (PSR) vital to vulnerable consumers and routes to redress e.g., via the Energy Ombudsman. The risk is that without proper consideration and assessment they could be further disadvantaged by this set of policy proposals. Not least because their ability to define their contract terms, including smart meter installation requests, may be restricted, in turn limiting their power to lower bills and reduce and/or use energy more sustainably. The challenge is further compounded by the lack of data on these consumers and those reselling energy. Given the usefulness of this data to multiple energy policy frameworks including the non-domestic smart meter rollout, DESNZ should consider coordinating this activity.

The impact of smart-contingent non-domestic contracts on small and microbusinesses

As forthcoming research from Consumer Scotland will highlight small businesses and microbusinesses are already struggling to secure fair and affordable energy contracts.[8] This is supported by recent research from the Federation of Small Businesses (FSB) which reports a significant drop in small business confidence, particularly in Scotland, with Scottish small businesses experiencing increased running costs, and utility costs cited as one of the biggest drivers.[9] It is important that this set of policy proposals helps reduce rather than exacerbate the cost-of-doing-business pressures small businesses and microbusinesses are currently experiencing. Especially given that they do not enjoy the same protections as domestic consumers in relation to the price cap, contractual cooling-off periods and around the resale of energy under the Maximum Resale Price (MRP) arrangements, which Consumer Scotland has argued Ofgem should consider extending to these businesses.[10]

According to 2025 FSB research 39% of small businesses have a meter installed. However, importantly, it also indicates that a significant proportion of small businesses, 45%, do not choose their supplier or contract. [11] Moreover, FSB research highlights that there is a discrepancy between small businesses renting their property and those who own their premises in terms of levels of smart meter installation. 31% of small businesses in rented premises have smart meters installed compared to 46% in owned premises. [12] As a result, putting in place the right incentives to encourage landlords to install smart meters and make other upgrades to their properties is vital in supporting more affordable and sustainable energy for small businesses and allowing them to flourish and contribute to economic growth. What is included in these policy proposals can certainly make a positive contribution but needs to be in done in tandem with efforts to strengthen consumer protections for small businesses and microbusinesses, further empower them to understand and secure the best energy deals and ensure that the right financial and other support is available regarding smart meter installations.

Third-party intermediaries (TPI) can play an important role in helping small businesses and microbusinesses secure affordable and sustainable energy. Therefore, it is essential that the design of new TPI regulation reflects changes in these policy proposals and facilitates effective communication by TPIs with their customers around smart-contingent fixed-term contracts. We welcome DESNZ’s commitment to engage with TPIs directly around these proposals.

The lessons from the domestic smart meter rollout and RTS switch off in Scotland

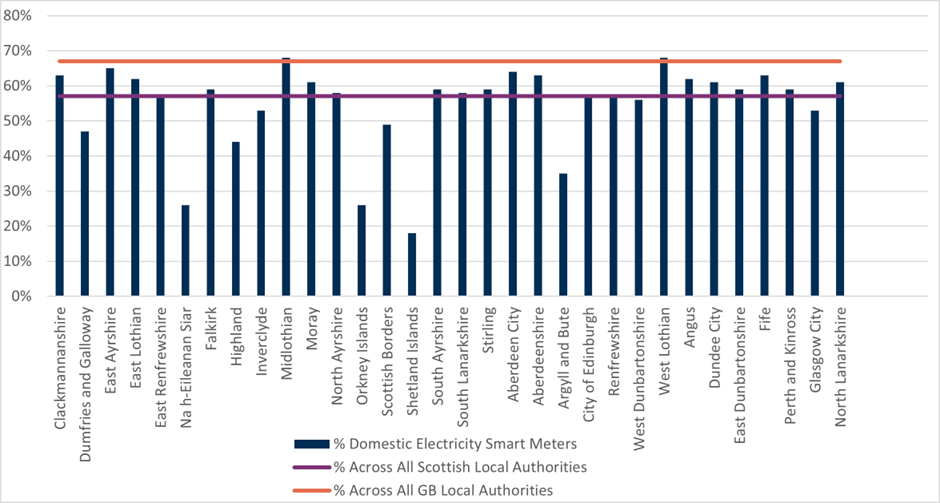

As of March 2025, and as shown in Figure 1., the penetration of smart meters in Scotland (57%) was lower than the rest of UK (67%), with rates significantly lower in particular local authorities[13].

Figure 1: Proportion of Domestic Electricity Smart Meters Operated by All Energy Suppliers by Scottish Local Authority, up to 31 March 2025

Factors behind this low installation rate include:

-

- technical signal and network challenges (although these may be mitigated in the coming years with recent regulatory changes to allow the use of 4G comms hubs in Scotland, as well as the rollout of VWAN networks),

- older building stock, and

- insufficient engineering resource and supplier incentive, especially in remote and sparsely populated areas. [14]

Similar issues were pinpointed in relation to the RTS switch off in Scotland. Both expose weaknesses in supplier-led transitions. In other European countries such as Italy and France, now with complete or high coverage, rollouts were led by the distribution system operator. Consumer Scotland welcomes the intervention by UK Government to drive the non-domestic rollout rather than leaving it solely to suppliers. With future rollouts, e.g., in installing new generations of smart meters, Consumer Scotland would urge UK Government to consider how adopting similar approaches to coordination and intervention could support more effective distribution.

We would also highlight the importance of tailored engagement strategies informed by data and understanding of specific groups and places. For example, to reach those in rural and remote communities in Scotland and ensure fair access to innovations and tools that can support more affordable and sustainable energy. Critically, reducing cost-of-living and cost-of-doing-business pressures, which can be significantly higher for businesses and households in areas such as remote and rural Scotland. [15]

Question 2. Are there any specific elements of the policy package where you agree/disagree? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

The main aspect of the policy proposals where we have particular concern is in relation to the lack of full consideration of the impact on households/domestic consumers, as articulated in the response to Q1.

We would welcome the opportunity to engage further with DESNZ, Ofgem, consumer and advice bodies, suppliers and others on this issue to ensure the policy package, including the consumer protection code and licence requirements, adequately reflects the needs and priorities of domestic consumers directly supplied or resold energy via non-domestic contracts and uses the opportunity to build much needed understanding and data in this area. Data that could be useful in informing multiple policy frameworks including targeting of support with bills and energy resale.

3. Do you have comments or views on the proposed consumer protection code of practice provisions, including:

a) whether they achieve the right balance between protecting consumers from the risks of inconsistent treatment from the market whilst minimising risks of misuse by stakeholders that may wish to avoid smart metering installations for other reasons, and

b) their alignment with other consumer protections? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

The consumer protection code of practice provisions offer a good starting point, but there is room for further refinement and development, and consideration of how these provisions will be implemented in practice. Particularly in relation to reflecting the impacts on, and needs of, domestic consumers supplied their energy via non-domestic contracts directly and domestic and non-domestic consumers resold energy via non-domestic contracts.

In the case of resale, consideration will need to be given to what responsibilities intermediaries such as landlords and site owners who manage the contract have (alongside suppliers) to ensure that both they themselves and those they are reselling energy to are ‘adequately informed about smart-contingent contracts and understand their implications’. In evidence provided to Ofgem around the review of MRP arrangements, Consumer Scotland highlighted that transparency and understanding around contractual arrangements in cases where energy is being resold is already problematic. To address this, we recommended that data on end-use consumers and resellers needs to be improved, the responsibilities of those managing energy contracts for others (e.g., landlords) need to be clearly articulated in relevant policy documents, and enforcement action and routes to redress strengthened. We believe these actions are relevant to, and would benefit, the implementation of this set of policy proposals.[16]

Groups with protected characteristics, such as those living with disabilities, are particularly at risk of energy affordability challenges, including energy debt according to Consumer Scotland’s Energy Affordability Tracker [17] and efforts need to be targeted at ensuring these policies do not further exacerbate these challenges, but support their access to more affordable and sustainable energy. We welcome the focus in the provisions in this regard but would argue they need to explicitly include domestic as well as non-domestic consumers. Data must be strengthened on this group of consumers if this provision is to be meaningfully implemented.

We agree with the provision to ensure timely smart meter appointments, also reinforced by Ofgem in their consultation on new Guaranteed Standards of Performance (GSOP) for specific elements of the smart meter consumer experience.[18] Ofgem highlight the importance of the six-week timeframe for installations irrespective of geographical location, citing the lower installation rates in Scotland.[19] Clearly, the code of conduct provisions and the GSOP smart meter standards of performance will need to align and be mutually reinforcing. We would welcome DESNZ and Ofgem considering including small businesses, and not just microbusinesses, within the scope of the GSOP smart meter standards. This could be important in achieving DESNZ’s aim of the rollout to ‘to reach the highest levels of uptake in small businesses’ and would help support small businesses, which as we have highlighted previously, continue to struggle with high energy costs and negotiating fair and affordable contracts.

4. Do you have comments or views on the proposed governance arrangements for the consumer protection code? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

Overall, the policy proposals seem reasonable, with responsibility for monitoring and evidencing supplier compliance primarily falling to the Retail Energy Code Company (RECCo) and performance assurance and enforcement action relating to that evidence falling to Ofgem.

More generally, Consumer Scotland suggests that the overall governance of the Retail Energy Code (REC) is reviewed and consideration is given to inviting representatives from statutory advocacy bodies to join the board to ensure the views of household and small business consumers are adequately represented in the development, monitoring and evaluation of smart-meter and other policy proposals. This would reflect the governance model of the Smart Energy Code which has consumer representation at the highest levels of decision-making.

5. Do you agree that the code of practice best sits within the Retail Energy Code? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

We believe that it makes sense to situate the code of practice within the REC. However, linked to the point above related to broader governance and consumer representation, Consumer Scotland would be keen to have a role through input and/or feedback, along with other relevant stakeholders, into the quantitative and qualitative measures that are developed and used by the REC code manger to monitor performance. On initial review these measures seem reasonable, however we believe they could be extended and refined.

On quantitative KPIs Consumer Scotland would recommend that as well as the number of contracts, installation appointments and actual installations, these also include measures of contracts and installations in locations or groups identified as hard-to-reach. This could help avoid slow and inequitable distribution, for example, as has occurred in the domestic smart meter rollout and with the RTS switch off in remote and rural Scotland.

On qualitative KPIs we would like to see some measure of consumers’ experience (perhaps disaggregated by consumer type) of contract terms, conditions and how they are being communicated developed.

6. Do you have views on the interactions between the policy proposals in Section One and commercial tenants’ rights to arrange for the installation of smart meters in their premises? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

We welcome the focus in the proposals to help incentivise and make the process easier for both commercial landlords and tenants to seek and/or accept smart meter installations. This is important, especially for smaller businesses, where earlier evidence referenced in response to question 2 suggests that those in rented premises have lower rates of smart meter installations compared to business-owned premises. The signposting and consideration of financing options for remedial works is also important and welcome, particularly for small businesses who continue to struggle with high energy costs. Boilerplate letters, as currently drafted, could also help facilitate the process.

However, we would urge DESNZ to consider the needs of domestic consumers who could be impacted by these proposals. It is important that they can benefit from the cheapest deals and the bill and energy savings that a smart-contingent contract could potentially bring them, particularly where a domestic contract is not available to them. For example, those with protected characteristics and potentially more at risk of energy debt [20] and who are more likely to live in flats and rented accommodation, and being supplied energy via a non-domestic contract arranged by their landlord. [21]

We would like to see these proposals provide additional clarity for commercial and domestic tenants and landlords, both with respect to what is expected of them under contracts and in terms of how they can engage constructively to facilitate the smart meter installation. This could be reflected in the wording of the policy and in adapting the boilerplate letters from landlord to tenant accordingly.

Overall, this is an area in which potential disputes could arise, and it is important that clear pathways to redress are articulated and understood by different types of consumers, landlords and suppliers. Consumer Scotland would welcome the opportunity to work with DESNZ and others to ensure that these are in place.

7. Do you agree with the proposals to publish a DESNZ policy statement regarding interactions between the policy and commercial tenants’ requests, alongside boilerplate letters for commercial landlords and tenants to support each other with the smart meter installation process? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

Yes, we would welcome the publication of a DESNZ policy statement in this regard, noting concerns around domestic consumers raised in response to Question 6.

In addition, consideration needs to be given to how differences in commercial leasing law between Scotland and other UK jurisdictions might have implications for these proposals. For example, in relation to responsibility for remedial costs (and which is explored further in the response to Question 9), landlord’s consent, or how other Scots laws and procedures may impact the proposals.

8. Do you have comments or views on the draft DESNZ policy statement and boilerplate commercial landlord/tenant letters included in Section Two? How could they be adapted or utilised to maximise smart meter uptake in the commercial private rented sector? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

Please see response to Question 6 in relation to reflecting the needs and rights of domestic consumers being supplied energy via non-domestic contracts in this regard.

Please also see responses to Questions 7 and 9 in relation to changes that may need to be made as a result of differences in commercial leasing law between Scotland and other UK jurisdictions.

9. Do you have views on the ideas for managing the interaction between these policy proposals and cases of remedial works needed in non-domestic premises? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

As highlighted previously differences in commercial leasing law between Scotland and other UK jurisdictions could have implications regarding responsibility for remedial works, dilapidations, improvements and landlord’s consent. In England, responsibility for remedial works would usually fall to tenants but in Scotland there is the potential for it to fall to the landlord (dependent on the exact terms of any repairing clause in the lease). This is something DESNZ will want to consider in the wording of the policy and the boilerplate letters provided.

The fact that DESNZ is working with energy suppliers to improve data on the types and costs of remedial works in smaller non-domestic premises is welcome and can support efforts to explore long-term financing options. We would agree that provisions in the consumer protection code to protect and minimise the cost of remedial works on organisations, particularly small and microbusinesses, is vital. Suppliers could support efforts to signpost current financing options and information could also be made within and/or alongside the boilerplate letters.

10. Do you have views on whether the policy proposals should apply only with respect to designated premises, or all non-domestic premises? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

Beyond a more general view that applying proposals to all non-domestic premises could have the potential to support wider efforts to change/flex energy demand, as well as reduce existing pressures on the network/grid, which in turn could lower bills for everyone, Consumer Scotland does not have any specific views on this matter.

13. Do you have views on whether the proposals in this consultation could be suitable for other specialist forms of energy contracts available in the non-domestic market? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

Just under a third of businesses in the UK are not on a fixed-term contract.[22] Many of those businesses, particularly small and microbusinesses, are likely to be on evergreen contracts or deemed/out-of-contract rates.[23] These are likely to be more expensive. This is not ideal for the smallest businesses already struggling to negotiate fair and affordable contracts, and more likely to be in debt [24] without the ability to switch, as the Debt Assignment Protocol (DAP) that allows customers to switch supplier even when in debt of up to £500 per fuel type only applies to domestic consumers. Although Ofgem regulation does state that microbusinesses cannot remain on a rollover contract for more than 12 months, disengaged businesses may simply be rolling from one poor-value deal to another.

DESNZ could initially consider requiring that suppliers more regularly set out options for microbusinesses and small businesses to move on to smart-contingent fixed-term contracts. This could be done at specific intervals and/or alongside auto renewal notices and would be in line with current supplier licence conditions that require suppliers to take all reasonable steps to ensure the terms of deemed contracts are not unduly onerous.

Over time, this could be reviewed, and ultimately all non-domestic contracts could become smart-contingent, including evergreen and deemed contracts. Making evergreen and deemed contracts smart-contingent could:

-

- Incentivise greater engagement between suppliers and small business and microbusiness consumers.

- Help prevent disengaged small and microbusinesses simply rolling from one poor-value deal to another.

- Increase awareness and monitoring by small business and microbusiness consumers of energy costs and lead them to negotiate more favourable rates and contracts, as well as flex demand.

16. Do you have views on, or suggestions to inform, the policy engagement strategy set out in Section Four? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

We welcome the proposed role for Smart Energy GB who already have expertise in communicating with microbusinesses around the benefits of smart meters. We believe there could be value in DESNZ and Smart Energy GB considering whether this role could be extended to include small businesses. Smart Energy GB can also draw on their experience of engaging with domestic consumers as part of the domestic rollout in communicating with those domestic consumers impacted by the non-domestic smart meter rollout.

Given the impact on some domestic consumers, the scope of engagement should encompass relevant stakeholders such as residential landlords’ organisations, tenants’ rights groups, park home site owners and residents’ associations, as well business representatives, commercial landlords’ organisations, trade associations, third party intermediaries and membership organisations. Together with representatives from suppliers, government (national and devolved), Smart Energy GB, local authorities, consumer bodies and advice organisations, these stakeholders can play a valuable role in effectively refining, targeting and delivering messages for different consumer groups. DESNZ could consider a working group bringing these representatives together to coordinate this activity, and which Consumer Scotland would welcome the opportunity to be part of. More broadly, engagement needs to link and align with the consumer engagement approaches developed to enhance wider consumer-led flexibility.

17. Do you have views on the proposals in relation to maintaining industry flexibility to manage the nuances of the 4G transition in the non-domestic sector, including with respect to installer capacity? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

We welcome DESNZ’ plans to consider how suppliers could be required to work together in installing meters in areas that are remote/rural. More collaborative effort to achieve installations in those areas could reduce the costs for all suppliers through more effective use of engineering resources. For public sector installations, there could be requirements on those public sector bodies to work together to arrange installations in groups in rural/remote areas, making more effective use of public resources.

18. Do you agree that the draft amendments to energy supplier licence conditions set out in Annex B implement the policy intentions proposed in Section One of this document? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

As highlighted throughout this response, DESNZ must consider how the language in the policy wording, the licence conditions and consumer protection provisions reflects the fact that this policy will impact both domestic and non-domestic consumers.

Q19. Do you agree that the draft amendments to energy supplier licence conditions set out in Annex B reflect the policy options with respect to scope set out in Section Three? Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

As highlighted throughout this response, DESNZ must consider how the language in the policy wording, the licence conditions and consumer protection provisions reflects the fact that this policy will impact both domestic and non-domestic consumers.

Q20. Do you agree that the draft Retail Energy Code schedule set out in Annex C implements the policy intentions proposed in Section One of this document. Please provide rationale and evidence to support your answer.

As per our response to Question 18. DESNZ must consider how the language in the policy wording, the licence conditions and consumer protection provisions reflects the fact that this policy will impact both domestic and non-domestic consumers.

For example, point 2.1 (b) (ii) currently reads as follows in relation to the requirement on suppliers to:

‘pay particular attention to the needs and circumstances of…any persons who reside or are accommodated at the Relevant [Non-Domestic/Designated] Premises…’

To better reflect the impact of these policies on domestic consumers and the role of intermediaries such as landlords in managing contracts and relationships with suppliers 2.1 (b) (ii) could be re-written as follows:

‘pay particular attention to the needs and circumstances of…domestic end-users who reside or are accommodated at the Relevant [Non-Domestic/Designated] Premises, with both parties to the Relevant smart-contingent contract working together to address these needs’

3. About us

Consumer Scotland is the statutory body for consumers in Scotland. Established by the Consumer Scotland Act 2020, we are accountable to the Scottish Parliament. The Act defines consumers as individuals and small businesses that purchase, use or receive in Scotland goods or services supplied by a business, profession, not for profit enterprise, or public body.

Our purpose is to improve outcomes for current and future consumers, and our strategic objectives are:

-

- to enhance understanding and awareness of consumer issues by strengthening the evidence base

- to serve the needs and aspirations of current and future consumers by inspiring and influencing the public, private and third sectors

- to enable the active participation of consumers in a fairer economy by improving access to information and support

Consumer Scotland uses data, research and analysis to inform our work on the key issues facing consumers in Scotland. In conjunction with that evidence base we seek a consumer perspective through the application of the consumer principles of access, choice, safety, information, fairness, representation, sustainability and redress.

4. Consumer Principles

The Consumer Principles are a set of principles developed by consumer organisations in the UK and overseas.

Consumer Scotland uses the Consumer Principles as a framework through which to analyse the evidence on markets and related issues from a consumer perspective.

The Consumer Principles are:

-

- Access: Can people get the goods or services they need or want?

- Choice: Is there any?

- Safety: Are the goods or services dangerous to health or welfare?

- Information: Is it available, accurate and useful?

- Fairness: Are some or all consumers unfairly discriminated against?

- Representation: Do consumers have a say in how goods or services are provided?

- Redress: If things go wrong, is there a system for making things right?

- Sustainability: Are consumers enabled to make sustainable choices?

Our response has been framed by our Consumer Principles. Reviewing policy against these principles enables the development of more consumer-focused policy and practice, and ultimately the delivery of better consumer outcomes.

5. Endnotes

[1] UK Government (2024) Clean Power 2030 Action Plan

[2] UK Government (2025) Clean flexibility roadmap

[3] Consumer Scotland (2024) Response to DESNZ consultation on smart metering policy framework post 2025

[4] ibid

[6] Ofgem (2025) Call for input: Reselling Gas and Electricity (pg.4)

[8] Consumer Scotland (forthcoming) Small business survey

[9] Federation of Small Businesses (2025) FSB urges Budget help as 1 in 4 Scottish small firms expect to shrink

[10] Consumer Scotland (2025) Response to Ofgem call for input on reselling gas and electricity: maximum resale price direction

[11] Federation of Small Businesses (2025) FSB urges Budget help as 1 in 4 Scottish small firms expect to shrink

[12] ibid

[13] UK Government Smart meter statistics

[14] Changeworks (2023) A Perfect Storm: Fuel Poverty in Rural Scotland, (p.20)

[15] Scottish Government (2023) Rural Scotland Data Dashboard: Overview

[16] Consumer Scotland (2025) Response to Ofgem call for input on reselling gas and electricity: maximum resale price direction

[17] Consumer Scotland (2025) Insights from the 2025 Energy Affordability Tracker (HTML)

[19] ibid

[21] Cavillo, C. and Martiskainen, M. (2024) Understanding the barriers and impacts of green choices on people with protected characteristic. Energy Demand Research Centre

[22] Utility Bidder (2025) 46 Business Energy Statistics and Industry Trends

[23] Ofgem (2024) Non-domestic Research Report

[24] ibid