1. Executive Summary

This report presents key messages and recommendations emerging from research, conducted on behalf of Consumer Scotland, on consumer behaviour and the transition to a circular economy. It builds on the findings of our report Consumer Perceptions of and Engagement with the Transition to Net Zero. This found that although levels of net zero awareness and concern are high, many consumers are unsure about what they can personally do to help Scotland meet net zero targets.[1]

Many consumers want to reduce their personal emissions with 80% of participants in our quantitative research agreeing that they would like to reduce the carbon emissions from the household items that they buy. However, this consumer concern about climate change is not translating into action that matches the pace and scale of change required. There is broad support for measures relating to reducing consumption, buying second hand, or increasing repair and re-use. However, consumers require more support to move beyond low impact changes and to enable levels of action to match those required to meet the challenge.

Transitioning to a circular economy is one of the significant challenges of our time. On average, people in Scotland consume more than double the sustainable level of material use which academics agree would still allow for a high quality of life: around 8 tonnes per person per year.[2] Supporting consumers to buy and waste less, extending the life of existing items and reusing resources will help to reduce the carbon footprint of people in Scotland.

Making sustainable choices more cost-effective and convenient for consumers is central to a successful transition to a circular economy. Purchasing decisions are influenced by a range of factors, including convenience, speed of purchasing, ingrained behaviours and price. Sustainability considerations compete with these factors and our research has shown that many consumers prioritise other factors such as cost and quality when making purchasing decisions. To support and encourage consumers to make changes to their purchasing decisions it will be important to highlight the wider benefits of changes to behaviours. Highlighting benefits such as economic growth, cost savings and health benefits will be central to encouraging more sustainable purchasing behaviours by consumers.

There is a need for a systemic approach, backed by robust impact assessments of new measures in order to support effective consumer engagement with the transition to a circular economy. Where new market measures such as products bans or new process requirements are introduced, it is important that wider consumer protections, regulations and incentives are in place from the outset. Clear leadership will be needed to develop infrastructure and systems needed to facilitate sustainable behaviour change. Policymakers must ensure that all consumers are able to adopt more sustainable behaviours, carefully balancing the current, and future, costs to individuals and society and prioritising a just transition.

In 2016 the Scottish Government published ‘Making Things Last: A Circular Economy for Scotland’, which set out the Scottish Government’s priorities for moving towards a more circular economy.

2. Who we are

Consumer Scotland is the statutory body for consumers in Scotland. Established by the Consumer Scotland Act 2020, we are accountable to the Scottish Parliament. Consumer Scotland’s purpose is to improve outcomes for current and future consumers and our strategic objectives are:

- to enhance understanding and awareness of consumer issues by strengthening the evidence base

- to serve the needs and aspirations of current and future consumers by inspiring and influencing the public, private and third sectors

- to enable the active participation of consumers in a fairer economy by improving access to information and support

Consumer Scotland uses data, research and analysis to inform our work on the key issues facing consumers in Scotland. In conjunction with that evidence base we seek a consumer perspective through the application of the consumer principles of access, choice, safety, information, fairness, representation, sustainability and redress.

Our general function is to provide consumer advocacy and advice with a view to achieving more positive consumer outcomes. We also have a role in a promoting sustainable consumption of natural resources, and other environmentally sustainable practices in relation to the acquisition, use and disposal of goods by current, and future, consumers in Scotland.

Consumer Scotland’s Strategic Plan for 2023-2027 sets out three cross-cutting themes which inform our focus and priorities across this period.[3] Understanding and influencing Scotland’s approach to climate change to ensure that this delivers effectively for consumers is one of these key themes.

Our 2024-25 Work Programme commits us to identifying how consumers can play a role in reducing consumption and getting the maximum use from our natural resources, contributing to the development of a circular economy.[4]

3. Introduction

A circular economy is part of the solution to the global climate emergency, ensuring that nothing goes to waste and that everything has value. Zero Waste Scotland describes it as 'make, use, remake' rather than 'make, use, dispose'.[5]

The transition to a circular economy can create a wide range of positive impacts, including reducing waste and pollution, conserving resources, creating jobs and fostering economic growth, lowering greenhouse gas emissions, improving social outcomes and fostering innovation.[6]

Transitioning to a circular economy is one of the significant challenges of our time. Scotland's per capita material footprint is nearly double the global average, with Scotland’s population consuming 21.7 tonnes of virgin resources per person, per year.[7] On average, people in Scotland consume more than double the sustainable level of material use which academics agree would still allow for a high quality of life: around 8 tonnes per person per year.[8] Supporting consumers to buy and waste less will help to reduce the carbon footprint of people in Scotland.

The Circularity Gap Report suggests that Scotland is currently only 1.3% 'circular', with more than 98% of materials extracted from virgin resources.[9] Increasing circularity could help to reduce emissions in Scotland by up to 43%.[10] Achieving this will require action at a number of levels, from Government, businesses, communities and individuals.

All sectors in the Scottish economy will need to play their part in the transition to a more circular economy. Governments, industries and regulators will need to support households, businesses and communities to make changes to their lifestyles, business practices, and consumption habits. Technological and design solutions will also be needed to enable innovation and support the removal of environmentally harmful products from the supply chain.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC) has estimated that over 60% of the emissions reductions that will be needed to meet net zero will be predicated on some kind of individual or societal behavioural change.[11] Supporting individual consumers to understand the changes that are required and putting the right mechanisms in place to enable them to make more sustainable choices, and change their consumption habits, will be critical to the transition to a circular economy.

4. Legislative and policy background

[12] The strategy set out ambitions in relation to waste prevention, the desire for products to be designed for longer lifespans and the importance of repair, reuse, recycling and producer responsibility.[13]

The Scottish Government consulted on proposals for a Circular Economy Bill in mid-2022 and subsequently published an analysis of consultation responses.[14] This followed on from a previous Scottish Government consultation on proposals for a Circular Economy Bill in 2019. [15] In tandem with the 2022 Bill consultation, the Scottish Government also consulted on ‘Delivering Scotland's circular economy: A Route Map to 2025 and beyond’ which aimed to complement the Bill consultation and provide wider context for the Bill.[16]

The Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill was introduced on 13 June 2023 and became an Act on 8 August 2024. It established the legislative framework to support Scotland’s transition to a zero waste and circular economy.[17] The Act requires Scottish Ministers to introduce measures to help develop a circular economy. These measures include:

- publishing a circular economy strategy

- developing circular economy targets

- reducing waste

- increasing penalties for littering from vehicles

- making sure individual householders and businesses get rid of waste in the right way

- improving waste monitoring[18]

In early 2024 the Scottish Government consulted on a draft Circular Economy and Waste Route Map to 2030, seeking views on various actions to accelerate more sustainable use of resources in Scotland, supporting the delivery of a circular economy to 2030 and reducing the emissions associated with resources and waste.[19]

5. About this report

In 2023/2024 Consumer Scotland significantly expanded our net zero and climate change evidence base by commissioning six research projects across a range of consumer markets. These projects used a range of research methods to examine in detail consumers’ attitudes, experiences, beliefs, behaviours and perceptions related to the transition to net zero and wider climate change adaptation and mitigation.

This report draws primarily on the findings from two of these projects:

- A quantitative survey of consumers’ general attitudes to net zero

- A qualitative project which explored consumers participation in the transition to net zero

The report presents our key messages and recommendations emerging from these projects as they specifically relate to consumer behaviour and the transition to a circular economy. It begins by summarising the key findings from these projects, as previously set out in more detail in our report Consumer Perceptions of and Engagement with the Transition to Net Zero.[20] It is important to consider these findings in this context, as consumer views on net zero more broadly inform attitudes and willingness to change in relation to circular economy measures. The report goes on to draw on aspects of the research which specifically address issues around the circular economy.

6. Key findings

Levels of net zero awareness and concern remain high, but consumers are less sure about what they can personally do to help Scotland meet net zero targets

Our survey research, conducted by YouGov, and undertaken between February and March 2024, demonstrated that consumers are generally concerned about climate change and the environment. Three in four (76%) respondents stated that they are either ‘very’ or ‘fairly’ concerned about climate change and the environment. Around one in four (23%) stated they are ‘not very’ or ‘not at all’ concerned.[21]

Despite being concerned about climate change, many consumers are unclear about how net zero will be achieved and how their actions can contribute to meeting emissions targets.[22] Our evidence indicates that many consumers have limited awareness of specific policies and terminologies surrounding net zero. Participants were not considering ‘net zero’ in their day-to-day lives nor viewing their everyday behaviours through this lens.[23]

While many consumers in Scotland say they are concerned about climate change, the majority are unsure about how they can personally contribute to the transition to net zero. Only 28% of our survey respondents said they know a lot/completely about what they need to do to help Scotland reach net zero by 2045.[24] Almost a third (31%) of respondents stated they know nothing/not much and 42% are in the middle on a 5-point scale of self-reported knowledge.[25]

Many consumers want to reduce the carbon emissions from their everyday activities but cost and convenience still drive purchasing decisions

Eighty per cent of participants in our quantitative research agreed that they would like to reduce the carbon emissions from the household items that they buy.[26] Those who agreed this was the case were asked to rank the top three reasons why they are not currently taking more action to do so. The most frequently selected reasons were:

- the cost of products which have lower environmental impact (63% of respondents ranking this as one of their top three reasons)

- lack of sufficient choice of products with lower environmental impact (62% of respondents ranking this)

- lack of clear labelling on the environmental impact of products allowing consumers to compare product choices (62% of respondents ranking this)[27]

Our research found that cost and convenience remain key factors in driving consumer purchasing decisions and can be barriers to behaviour change. Where consumers do take sustainable actions, these are often more influenced by ease and cost than by environmental benefits.[28]

Our qualitative research, conducted by Thinks Insight & Strategy during March 2024, found that consumers are motivated both by behaving in what they perceive as being a more ethical and responsible way, and by benefitting more materially, for example by saving money.[29] Where participants are consciously engaging in sustainable behaviours, this is usually motivated by factors such as saving money.[30]

Our quantitative research asked respondents if they thought they considered the environmental impact of purchases more, less or the same as other people in Scotland. Over a third (37%) of respondents stated that they thought they considered the environmental impact of purchases more than other people in Scotland, including 6% who thought they considered the impact much more.[31]

Current levels of consumer concern about climate change are not resulting in action that matches the pace and scale of change required

Our quantitative research found that, in relation to general purchasing behaviours, while around half (52%) say that they are likely to change their purchasing habits in the next year as a result of environmental concerns, only one in ten (10%) say they are ‘very likely’ to do so.[32] However, even among those consumers who say they are very/fairly concerned about climate change, this only rises to 13%, highlighting that concern about climate change is not currently translating into widespread change in purchasing habits.[33]

However, the degree to which consumers state they are likely to change purchasing habits as a result of environmental concerns is much higher among those who are very/fairly concerned about climate change when compared to those who are not very/at all. Those expressing higher concern about climate change are also more likely to say they have either taken sustainable actions previously or are likely to change their purchasing habits in the next year as a result of concerns for the environment. Levels of self-reported knowledge also impact on this. Among those who say they know (either completely or a lot) about what they need to do to help Scotland reach net zero by 2045, 70% say they are likely to make a climate-related change to their purchasing behaviours in the next 12 months, twice as many as those who say they know not much or nothing (34%).[34]

Our quantitative research also asked consumers about the extent to which sustainability concerns influenced their purchasing decisions across five product categories: food, clothing, household appliances, electronics and travel. Across all five categories, the proportion of consumers who report being always/sometimes influenced by sustainability concerns is at a similar level, ranging from 38% for travel to 51% for food. However, for all of these categories, only around one in ten say that their choices are always influenced by sustainability concerns.[35]

Consumers are open to circular economy measures, but they require more support to move beyond low impact changes

Our research found that everyday behaviours, such as recycling, are considered accessible, low effort and unlikely to significantly alter routines. As a result of this, such behaviours have become embedded within participants’ routines and are frequently observed, regardless of participants’ personal views on sustainability.[36] Behaviours such as recycling are generally considered ‘the right thing to do’ and are motivated by social expectations and a sense of guilt about not meeting these expectations:[37]

“I don’t use single use plastic anymore, I walk or cycle whenever I can rather than using the car, I fully recycle. I honestly think I do these things to feel less guilty rather than thinking that they are making much of a difference.” (Female, Eco-Reactive, Urban, 26-35.)

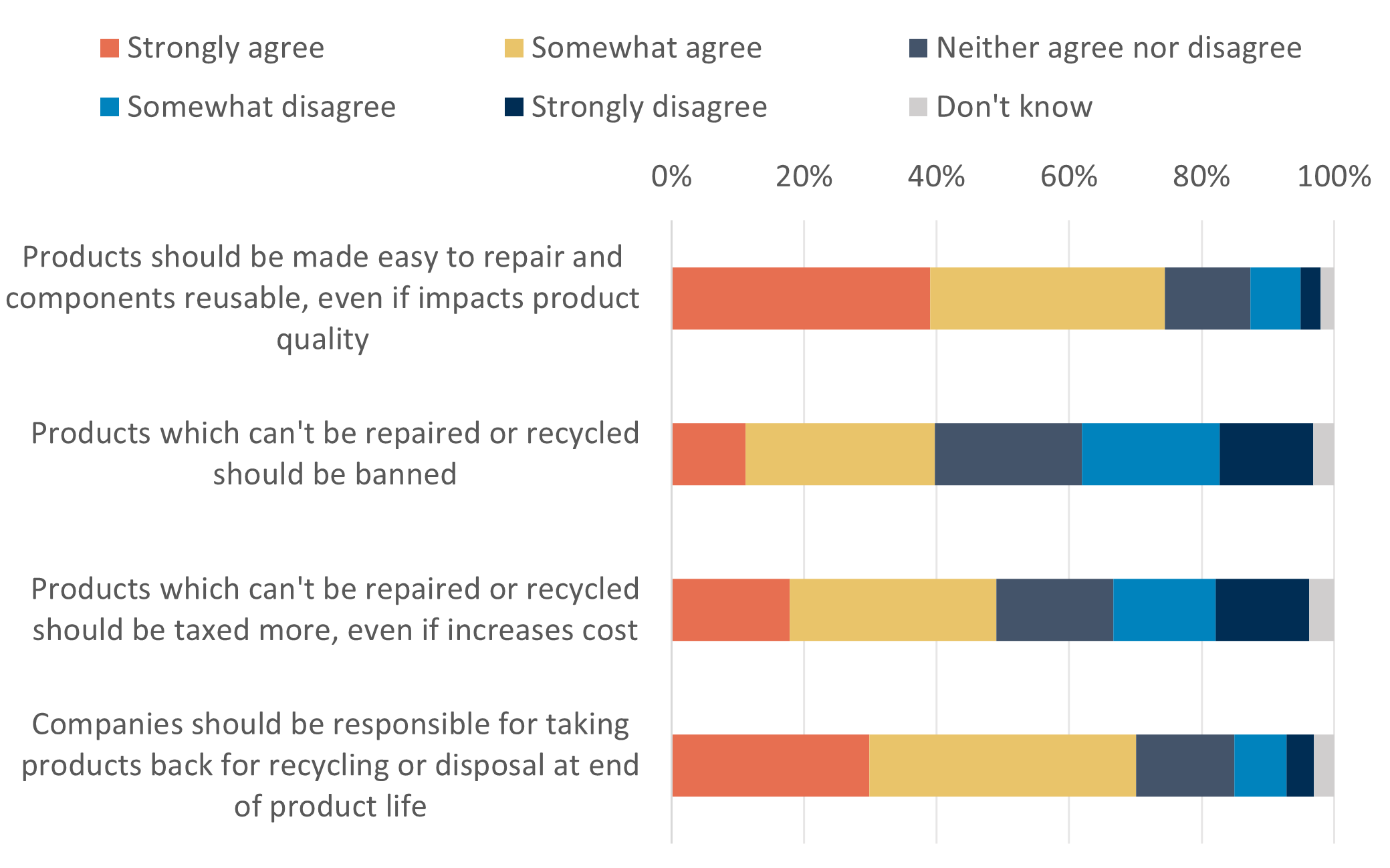

Our quantitative research showed broad consumer support for a range of circular economy measures. Respondents were asked to what extent they agreed with the following statements:

- ‘Products should be made so that they are easy to repair and their components can be re-used, even if this impacts product quality’ (74% agreed including 39% who strongly agreed)

- ‘Products which can't be repaired or recycled should be banned’ (40% agreed including 11% who strongly agreed)

- ‘Products which can't be repaired or recycled should be taxed more than those that can be, even if this increases their cost’ (49% agreed including 18% who strongly agreed

- ‘Companies that sell products should be responsible for taking them back for recycling or disposal at end of product life, even if the consumer is responsible for sending the product back to them’ (70% agreed including 30% who strongly agreed)[38]

Chart 1: There is broad consumer support for a range of circular economy measures

Percentage of respondents agreeing or disagreeing with measures to promote a circular economy

Source: Consumer Scotland survey of consumers’ general attitudes to net zero (2024),

Question 8 (base = 2062)

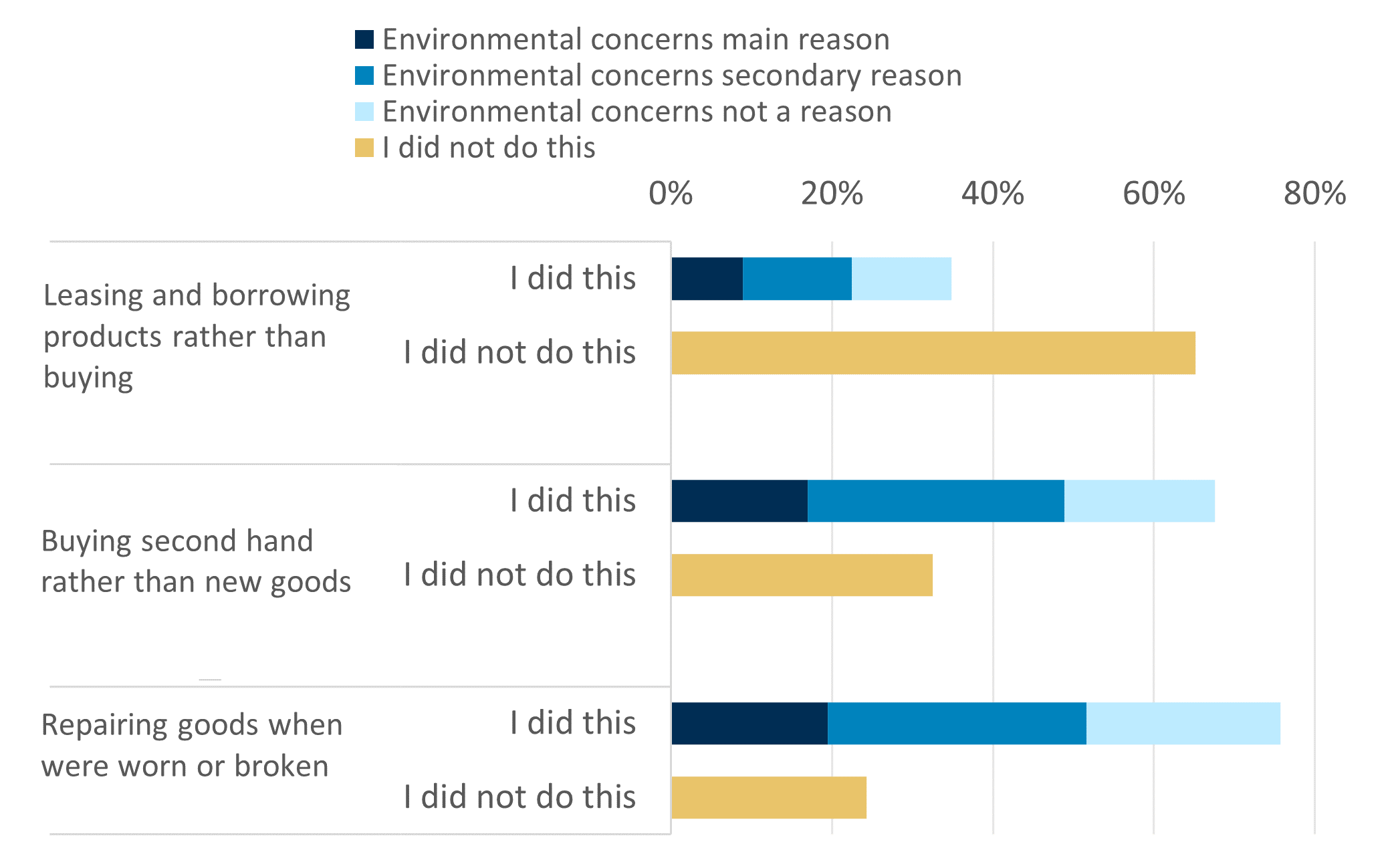

There is some consumer support for measures relating to reducing consumption, buying second hand, or increasing repair and re-use

We asked respondents if they had taken actions focused on reducing their consumption and re-using or recycling products in the past year, and if so, to what extent environmental concerns were a reason they did this. The purchasing behaviours asked about were: repairing goods when they were worn or broken, buying second hand rather than new goods, and repairing goods when they were worn or broken.

Of the three purchasing behaviours asked about, repairing goods when they were broken is the most common action that consumers report having taken, with just over three in four (76%) saying they have done this in the last year. Just over half (52%) say that environmental concerns were a factor in their decision to do this, including one in five (19%) saying this was the main reason for repairing goods when they were broken.[39]

Around two-thirds (68%) of consumers in Scotland reported having purchased second hand rather than new goods in the past year. Almost half (49%) stated that environmental concerns were a factor in their decision to do this, including 17% stating that environmental concerns were the main reason for buying second hand rather than new goods.[40]

Leasing and borrowing products rather than buying is less common, with just over a third (35%) reporting having done this in the past year. Just over one in five (22%) stated that environmental concerns were a reason for doing this, including just under one in 10 (9%) stating that environmental reasons were the main reason for leasing and borrowing products rather than buying.[41]

Chart 2: There is varying participation in purchasing behaviours related to reducing consumption, buying second hand, or increasing repair and re-use

Percentage of respondents who took the listed actions, and whether environmental concerns were a reason for doing so

Source: Consumer Scotland survey of consumers’ general attitudes to net zero (2024), Question 9 (base = 2062).

It should be noted that the proportion of consumers reporting that they took these specified actions did not differ greatly across groups when compared against consumers reported levels of concerns about climate change, although the small differences are statistically significant. There was a far greater difference in the proportion of consumers who reported that they had taken such actions primarily for environmental reasons. Therefore, while there is a difference in the proportion of consumers who report being motivated to act by environmental reasons, concern about climate change is not a major driver of action.

When looking at demographics, our research found that women are more likely to report doing all three of these for environmental reasons. This was the case for repairing worn or broken goods (58% vs 45% of men), buying second hand rather than new (56% vs 41% of men) and leasing or borrowing (26% vs 19% of men). [42]

Younger respondents (aged under 35) are also more likely to report higher instances of undertaking these behaviours for environmental reasons. Those under 35 were more likely to report environmental concerns were a reason for buying second hand (65% vs. 49% of all respondents), repairing worn or broken goods (61% vs. 52% of all respondents) and leasing or borrowing rather than buying (34% vs. 22% of all respondents).[43] Consistent with our finding above, there were greater differences between groups in relation to the stated reason for taking action than the level of action actually taken by consumers.

Reasons for purchasing household goods

In our quantitative research, consumers were asked about their most recent incidence of purchasing items in four different categories (clothing, a piece of furniture, an electronic device and a home appliance), and whether they were replacing another item or adding something new to their belongings.

Table 1: Reasons for buying items vary depending on the category of item bought

Reason for buying last clothing, furniture, electronic or home appliance item

|

Action |

Clothing |

Furniture |

Electronic device |

Home appliance |

|

Replacing an item that was broken |

18% |

32% |

50% |

59% |

|

Replacing an item that was old or out of fashion |

18% |

16% |

17% |

8% |

|

Adding something new to my belongings |

39% |

22% |

17% |

14% |

|

Replacing an item that no longer fit (i.e. too small or too large) |

18% |

5% |

2% |

2% |

|

Net: Replacing an item |

54% |

53% |

70% |

69% |

Source: Consumer Scotland survey of consumers’ general attitudes to net zero (2024), Question 22 (base = 2062)

Over two-thirds (70%) of consumers reported that the last electronic device they bought was to replace another item, including 50% who said that this was specifically replacing a broken item.[44] Similar figures are seen for home appliances, with 69% saying the last one they bought was a replacement for another item, including 59% saying the previous item was broken.[45]

While consumers were also more likely to report that the last item of clothing they bought was to replace another piece of clothing (54%), this is the only category where a sizeable minority report that they were adding something new to their belongings (39%)[46]. Those who say they are very or somewhat concerned about climate change are slightly less likely to report that the last item of clothing they bought was adding something new to their belongings than those who are not very or not at all concerned about climate change (37% vs 44%). [47] Women are also more likely to say that their last clothing purchase was made to add something new to their belongings (43% vs 34% of men).[48]

Our quantitative research also asked respondents about the most common action taken when an item was broken or damaged. For each of the four product categories, the most common action taken was to take the item to the local authority’s recycling centre (clothing: 20%, furniture: 35%, electronic device: 37%, home appliance: 39%).[49] After this, the actions taken varied more depending on the category. However, aggregating the proportion who said they either repaired it, recycled it, sold it or gave it away for free shows that people are most likely to do this for furniture (86%), followed by home appliances (71%), electronic devices (66%), and clothing (65%).[50]

Use of single use plastics and reusable cups

As highlighted above, the proportion of consumers who report being always influenced by sustainability concerns is only around one in ten for each of the listed categories of food, clothing, household appliances, electronics and travel.[51] Although up to half of respondents report being always or sometimes influenced by sustainability concerns, these figures indicate that despite consumers making occasional efforts to make more sustainable choices, sustainability is not an integral factor in consumption decisions.

Our quantitative research asked consumers if their purchasing behaviours had been influenced by a product’s materials or packaging in the last year. Just over one third (36%) reported having avoided buying products containing non-recyclable/single-use packaging, while a similar proportion (35%) have chosen to buy a product based on whether its packaging was reusable and recyclable.[52] A slightly lower number of respondents reported having chosen whether to buy a product based on the environmental impact of the materials of the product itself (27%).[53] Overall, 54% report doing at least one of these in the last year.[54]

Our quantitative research asked consumers who had avoided buying products containing non-recyclable/single use plastics about their reasons for avoiding buying these. The top reasons for this were:[55]

- It ends up in landfill (65%)

- It takes a long time to decompose (55%)

- It contributes to ocean pollution (51%)

- It harms marine animals and birds (46%)

- It contributes to carbon emissions (30%)

- It contaminates our food chain (20%)

Reducing the level of consumption of single use items will be a core element of the transition to a more circular economy. As part of this, the Scottish Government is currently consulting on the approach to implementing a charge for single-use disposable beverage cups. When asked about habits relating to reusable cups, 62% of respondents to our survey stated that they bring a reusable cup with them when away from home.[56] Of this, just under a third (31%) stated that environmental concerns were a reason for doing this, including 17% stating that environmental concerns were the main reason for doing this.[57] Women were more likely than men to report doing this (70% vs. 54%) along with those in the younger age category (78% of those aged 16-34 vs 62% of all respondents).[58]

When considering reasons for not bringing a reusable cup with them when away from home, the most frequently cited reason was ‘I haven’t thought about it’, with around a third (36%) selecting this response.[59] ‘Too much hassle’ (19%) and doesn’t appeal to me (15%) were the next most frequently selected options.[60]

7. Key messages for policy and decision makers

A systemic approach, backed by robust impact assessments of new measures, is needed to support effective consumer engagement with the transition to a circular economy

To support consumers to change their behaviours in a real, impactful and long-term way, there is an urgent need for systemic action at all levels of government and industry. Clear leadership will be needed in developing infrastructure and systems to facilitate sustainable behaviours. Policymakers must ensure that all consumers can adopt more sustainable behaviours, carefully balancing the current, and future, costs to individuals and society and prioritising a just transition.

Government policies, regulatory arrangements and infrastructural changes are required to create the conditions for an enabling environment. They will act as vital cornerstones and will drive tangible and sustainable consumer shifts towards net zero. Making and communicating strategic decisions about investments and priorities will also be key to obtaining effective consumer engagement.

There is a need for a system-level design which fully considers the need for regulation, including the design of incentives, and the banning or taxing of problematic products, where appropriate, as part of the solution. This is consistent with the findings of the Climate Change Committee, who have called for more support for people to make sustainable choices, including through providing regulation and incentives, where powers are devolved.[61]

The Scottish and UK Governments should undertake robust modelling, analysis and assessment of the consumer impact of the changes required. Our definition of consumer includes small businesses and we note the importance of assessing the impacts on small businesses along with individual consumers. This is especially necessary where high volumes of consumers are likely to be impacted by changes and where multiple measures will be implemented, in order to assess the cumulative impacts and the interactions between these measures.

Such analysis and modelling of proposed measures will be essential to guide both provision of targeted financial support and the implementation of regulation where required. There is a need to understand the costs of proposals and identify when and where these costs are likely to fall. Clear oversight of this will help to avoid any unintended consequences and minimise detriment for consumers, particularly those in vulnerable circumstances.

The timely publication of clear, robust and well communicated plans and strategies, such as the Climate Change Plan, Circular Economy Strategy and Circular Economy and Waste Routemap, will be essential for consumers to understand and engage with the changes that they are being asked to make. It is important that consumers can understand both the impact that these changes will have on their lives along with contribution of these changes in helping to move to a more circular economy across Scotland.

Making sustainable choices more cost-effective and convenient for consumers is central to a successful transition to a circular economy

The findings of our research show that the main barriers to consumers undertaking more sustainable behaviours relate to cost, convenience and accessibility. Purchasing decisions are influenced by a range of factors, including convenience, speed of purchasing, ingrained behaviours and price. Sustainability considerations compete with these factors and our research has shown that sustainability concerns do not currently appear to drive consumer purchasing decisions, with many consumers prioritising other factors such as cost and quality.

More should be done to highlight the potential for economic growth and community development that can come from the transition to a circular economy. The draft Circular Economy and Waste Routemap highlights the range of areas that can be positively impacted by the transition to a circular economy, including our economy and our society. The Routemap notes the economic benefits including opening up new market opportunities, improving productivity, and increasing self-sufficiency and resilience by reducing reliance on international supply chains and global shocks.[62] The Routemap also highlights benefits to our society including providing local employment opportunities and lower cost options to access goods.[63]

Given that many consumer purchasing decisions are more influenced by factors such as cost and convenience rather than sustainability, it will be important to highlight the wider benefits of changes to behaviours to encourage buy in and engagement. Highlighting benefits such as economic growth, cost savings and health benefits will be central to encouraging more sustainable action by consumers. By highlighting these benefits, government and other stakeholders can maximise the opportunity to engage consumers, particularly those who are less motivated by sustainability concerns. Greater levels of consumer behaviour change may also be facilitated by supporting consumers to understand the combined impact of smaller individual changes.

Our qualitative research found that concern about climate change at an individual level wasn’t always necessary for change to take place. Social factors, such as norms, networks and relationships along with material factors, such as infrastructure accessibility, can have a substantial impact on consumer behaviour change.

Governments and other key stakeholders should ensure that any changes to policy should include clear, specific and targeted information for consumers about how the changes will impact them. This should be given particular consideration where there will be a range of policies relevant in an area, such as the charge for single use cups and the deposit return scheme.

Consumers need more support to move their actions higher up the waste hierarchy

The waste hierarchy is a framework that guides the overall approach to managing Scotland's waste. It identifies the prevention of waste as the highest priority, followed by reuse, recycling, recovery of other value such as energy, with disposal as the least desirable option.[64]

If a transition to a circular economy is to be achieved, there must be a system in place that properly supports consumers to make meaningful behaviour changes which move beyond the lower impact solutions. Our research has shown that more ‘low effort’ behaviours such as recycling have become established norms regardless of views of sustainability. However, in order to make the changes that are required, efforts will need to focus more on reducing consumption, product re-use, and extracting maximum value from existing resources.

In order to support consumers to make meaningful behaviour changes which move beyond lower impact solutions, the Circular Economy Strategy should keep consumers at the centre of the process, making it as clear and straightforward as possible for them to make the informed and impactful choices that are required to support the transition to a circular economy.

Consumers and businesses will need support and information to change current purchasing behaviours. This information must deliver clarity, consistency and certainty about why these changes are needed and the options available to meet consumer needs. There are a wide range of current and upcoming consumer facing policies in this space such as a deposit return scheme, the charge on single use cups and other secondary legislation coming from the Circular Economy Act, including bans on the destruction of unsold consumer goods and measures to improve disposal of household waste. It is essential that consumers are well informed about the impact of each of these.

It is also important that consideration is given to the overall choice architecture that consumers are faced with when making decisions. There is a need for the Scottish Government to carry out modelling and analysis of key change processes that consumers will be required to navigate. This should include mapping out the journey that consumers will take when implementing key changes to behaviours as a result of legislative and policy developments such as the introduction of charges for single use items and changes to household recycling provision.

To mitigate against harm being caused to consumers as a result of the implementation of charges for single use items, there must be accessible and affordable sustainable alternatives available to all consumers that fit their needs. This will form a key element of the enabling environment that will be required for consumers to make the changes that are being asked of them.

Charges for single-use items are only one part of the solution. Facilitating greater consumer awareness and engagement with reducing consumption of single-use items through a sustained behaviour change campaign will also be important. Work must also continue with product designers and manufacturers to develop more sustainable products, for example through more research into understanding alternative materials which can replace single-use items, providing incentives to manufacturers to find solutions and exploring technological advances.

8. Recommendations

The Scottish Government must ensure that any secondary legislation made under the Circular Economy Act focusses on moving action higher up the waste hierarchy and addresses the problems of overconsumption and unsustainable resource use.

The UK and Scottish Governments should work together and with regulators to ensure that where new market measures such as products bans or new process requirements are introduced, that wider consumer protections, regulations and incentives are in place.

The Scottish Government should carry out modelling and analysis of key change processes that consumers will be required to navigate. This should be part of the process of developing plans and strategies such as the Circular Economy Strategy and the final Circular Economy and Waste Routemap.

The Scottish Government should work with Zero Waste Scotland, business groups and enforcement bodies and the Regulatory Review Group to determine what incentives and regulations may be developed to remove less sustainable options from the market or restrict their usage over time, for example through secondary legislation implemented under the Circular Economy Act such as banning the destruction of unsold consumer goods.

9. Next steps

Consumer Scotland works to improve outcomes for current and future consumers in Scotland. As set out in our Strategic Plan, one of our three cross-cutting themes is climate change adaptation and mitigation. We will continue to build our wider evidence base in relation to climate change and sustainability. Our future work in this area will include:

- Continuing to use the findings of our research to advocate for consumers, engaging with the Scottish Government and other stakeholders to provide a consumer perspective on the changes that will be required for the transition to a circular economy.

- Continue to influence policy and practice, including the implementation of charges for single use cups, Deposit Return Scheme, packaging reform and the development of the Circular Economy Strategy and Routemap

- Continuing to work with stakeholders, using our insights to advocate for action by governments, regulators and businesses that delivers positive outcomes for consumers

- Publishing further research reports on net zero related issues such as transport, post decarbonisation and low carbon technology

10. Endnotes

[1] Consumer Scotland (2024) Consumer perceptions of and engagement with the transition to net zero. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/knjbr55y/xm24-02-consumer-perceptions-of-and-engagement-with-the-transition-to-net-zero-final-report.pdf

[2] Zero Waste Scotland - Circular Economy Bill: Continuing Scotland’s sustainable journey available at: https://assets.website-files.com/5e185aa4d27bcf348400ed82/6399cc007f63ad41fae0b240_CGR%20Scotland.pdf

[3] Consumer Scotland (2023) Strategic Plan 2023-2027. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/impact-assessment/2023/06/circular-economy-scotland-bill-equality-impact-assessment/documents/circular-economy-scotland-bill-equality-impact-assessment/circular-economy-scotland-bill-equality-impact-assessment/govscot%3Adocument/circular-economy-scotland-bill-equality-impact-assessment.pdf https://consumer.scot/publications/strategic-plan-2023-2027-html/#:~:text=Consumer%20Scotland%20seeks%20to%3A%201%20enhance%20understanding%20and,economy%20by%20improving%20access%20to%20information%20and%20support

[4] Consumer Scotland (2024) Work Programme 2024-25. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/t13bxnd2/consumer-scotland-work-programme-2024-2025.pdf

[5] Zero Waste Scotland (2023) What is a circular economy? Available at: https://www.zerowastescotland.org.uk/resources/about-circular-economy

[6] Zero Waste Scotland (no date) Circular economy. Available at: https://www.zerowastescotland.org.uk/topics/circular-economy

[7] Circle Economy (2022) The Circularity Gap Report: Scotland. Available at: https://assets-global.website-files.com/5e185aa4d27bcf348400ed82/6399cc007f63ad41fae0b240_CGR%20Scotland.pdf

[8] Zero Waste Scotland - Circular Economy Bill: Continuing Scotland’s sustainable journey available at: https://assets.website-files.com/5e185aa4d27bcf348400ed82/6399cc007f63ad41fae0b240_CGR%20Scotland.pdf

[9] Circle Economy (2022) The Circularity Gap Report: Scotland. Available at: https://assets-global.website-files.com/5e185aa4d27bcf348400ed82/6399cc007f63ad41fae0b240_CGR%20Scotland.pdf

[10] Circle Economy (2022) The Circularity Gap Report: Scotland. Available at: https://assets-global.website-files.com/5e185aa4d27bcf348400ed82/6399cc007f63ad41fae0b240_CGR%20Scotland.pdf

[11] Committee on Climate Change (2019) Net Zero – the UK’s contribution to stopping global warming. Available at: https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Net-Zero-The-UKs-contribution-to-stopping-global-warming.pdf

[12] The Scottish Government (2016) Making Things Last: A Circular Economy Strategy for Scotland. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2016/02/making-things-last-circular-economy-strategy-scotland/documents/00494471-pdf/00494471-pdf/govscot%3Adocument/00494471.pdf

[13] The Scottish Government (2016) Making Things Last: A Circular Economy Strategy for Scotland. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2016/02/making-things-last-circular-economy-strategy-scotland/documents/00494471-pdf/00494471-pdf/govscot%3Adocument/00494471.pdf

[14] Scottish Government (2022) Delivering Scotland's circular economy: Proposed Circular Economy Bill - Consultation analysis. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/delivering-scotlands-circular-economy-proposed-circular-economy-bill-consultation-analysis/

[15] SPICe (2023) Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill briefing. Available at: https://bprcdn.parliament.scot/published/2023/9/22/69d34394-cbf1-4310-ad5e-0e4c804a1e9b/SB%2023-36.pdf

[16] SPICe (2023) Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill briefing. Available at: https://bprcdn.parliament.scot/published/2023/9/22/69d34394-cbf1-4310-ad5e-0e4c804a1e9b/SB%2023-36.pdf

[17] Scottish Government (2023) Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill Equality Impact Assessment. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2016/02/making-things-last-circular-economy-strategy-scotland/documents/00494471-pdf/00494471-pdf/govscot%3Adocument/00494471.pdf

[18] Scottish Parliament (2024) Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill. Available at: https://www.parliament.scot/bills-and-laws/bills/s6/circular-economy-scotland-bill

[19] Scottish Government (2024) Scotland's draft Circular Economy and Waste Route Map to 2030 – consultation. Available at: https://consult.gov.scot/zero-waste-delivery/draft-circular-economy-and-waste-route-map/

[20] Consumer Scotland (2024) Consumer perceptions of and engagement with the transition to net zero. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/knjbr55y/xm24-02-consumer-perceptions-of-and-engagement-with-the-transition-to-net-zero-final-report.pdf

[21] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 1). Available at:

[22] Consumer Scotland (2024) Consumer perceptions of and engagement with the transition to net zero. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/knjbr55y/xm24-02-consumer-perceptions-of-and-engagement-with-the-transition-to-net-zero-final-report.pdf

[23] Consumer Scotland (2024) Consumer perceptions of and engagement with the transition to net zero. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/knjbr55y/xm24-02-consumer-perceptions-of-and-engagement-with-the-transition-to-net-zero-final-report.pdf

[24] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 2). Available at:

[25] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 2). Available at:

[26] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 12) Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[27] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 13) Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[28] Consumer Scotland (2024) Consumer perceptions of and engagement with the transition to net zero. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/knjbr55y/xm24-02-consumer-perceptions-of-and-engagement-with-the-transition-to-net-zero-final-report.pdf

[29] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[30] Consumer Scotland (2024) Consumer perceptions of and engagement with the transition to net zero. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/knjbr55y/xm24-02-consumer-perceptions-of-and-engagement-with-the-transition-to-net-zero-final-report.pdf

[31] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 4). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[32] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 5). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[33] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 5). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[34] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 5). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[35] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 24). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[36] Consumer Scotland (2024) Consumer perceptions of and engagement with the transition to net zero. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/knjbr55y/xm24-02-consumer-perceptions-of-and-engagement-with-the-transition-to-net-zero-final-report.pdf

[37] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[38] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 8). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[39] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 9). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[40] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 9). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[41] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 9). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[42] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 9). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[43] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 9). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[44] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 22). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[45] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 22). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[46] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 22). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[47] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 22). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[48] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 22). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[49] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 23). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[50] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 23). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[51] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 24). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[52] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 10). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[53] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 10). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[54] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 10). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[55] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 11). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[56] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 31). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[57] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 31). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[58] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 31). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[59] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 32). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[60] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 32). Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-survey-yougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[61] Climate Change Committee (2024) 2024 Progress Report to Parliament. Available at: https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/progress-in-reducing-emissions-2024-report-to-parliament/#publication-downloads

[62] Scottish Government (2024) Scotland’s Circular Economy and Waste Route Map to 2030 Consultation. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/consultation-paper/2024/01/scotlands-circular-economy-waste-route-map-2030-consultation/documents/scotlands-circular-economy-waste-route-map-2030-consultation/scotlands-circular-economy-waste-route-map-2030-consultation/govscot%3Adocument/scotlands-circular-economy-waste-route-map-2030-consultation.pdf

[63] Scottish Government (2024) Scotland’s Circular Economy and Waste Route Map to 2030 Consultation. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/consultation-paper/2024/01/scotlands-circular-economy-waste-route-map-2030-consultation/documents/scotlands-circular-economy-waste-route-map-2030-consultation/scotlands-circular-economy-waste-route-map-2030-consultation/govscot%3Adocument/scotlands-circular-economy-waste-route-map-2030-consultation.pdf

[64] Scottish Government (2024) Scotland’s Circular Economy and Waste Route Map to 2030 Consultation. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/consultation-paper/2024/01/scotlands-circular-economy-waste-route-map-2030-consultation/documents/scotlands-circular-economy-waste-route-map-2030-consultation/scotlands-circular-economy-waste-route-map-2030-consultation/govscot%3Adocument/scotlands-circular-economy-waste-route-map-2030-consultation.pdf