1. About us

Consumer Scotland is the statutory body for consumers in Scotland. Established by the Consumer Scotland Act 2020, we are accountable to the Scottish Parliament. The Act defines consumers as individuals and small businesses that purchase, use or receive in Scotland goods or services supplied by a business, profession, not for profit enterprise, or public body.

Our purpose is to improve outcomes for current and future consumers, and our strategic objectives are:

- to enhance understanding and awareness of consumer issues by strengthening the evidence base

- to serve the needs and aspirations of current and future consumers by inspiring and influencing the public, private and third sectors

- to enable the active participation of consumers in a fairer economy by improving access to information and support

Consumer Scotland uses data, research and analysis to inform our work on the key issues facing consumers in Scotland. In conjunction with that evidence base we seek a consumer perspective through the application of the consumer principles of access, choice, safety, information, fairness, representation, sustainability and redress.

Consumer principles

The Consumer Principles are a set of principles developed by consumer organisations in the UK and overseas.

Consumer Scotland uses the Consumer Principles as a framework through which to analyse the evidence on markets and related issues from a consumer perspective.

The Consumer Principles are:

- Access: Can people get the goods or services they need or want?

- Choice: Is there any?

- Safety: Are the goods or services dangerous to health or welfare?

- Information: Is it available, accurate and useful?

- Fairness: Are some or all consumers unfairly discriminated against?

- Representation: Do consumers have a say in how goods or services are provided?

- Redress: If things go wrong, is there a system for making things right?

- Sustainability: Are consumers enabled to make sustainable choices?

We have identified access, information and fairness as being particularly relevant to the consultation proposal that we are responding to.

2. Our response

Consumer Scotland welcomes Ofgem’s efforts to introduce a Debt Relief Scheme (DRS). Done right, it has the potential to provide much-needed support to those in precarious financial situations, while also benefiting the market more broadly by reducing the level of bad debt, the cost of which is borne by all consumers. There is clearly a balance to be struck between maximising the relief provided to debt-affected customers and minimising the costs to wider consumers. We consider that Ofgem’s proposals will, in general, help to strike this balance.

Consumer Scotland broadly supports the proposed DRS eligibility criteria. The scheme provides a straightforward and in many cases automated means of writing off historic energy debt for consumers on means-tested benefits. We welcome Ofgem’s proposal to use DWP-held benefits data to avoid any barriers to access to debt relief that the previously proposed supplier-held Warm Home Discount (WHD) may have presented for consumers in Scotland.

For disengaged consumers, we welcome Ofgem’s proposal to provide a range of pathways to access debt relief. Findings from our research suggest that indebted consumers are often not going to their energy supplier for advice. The DRS therefore presents an opportunity to have meaningful discussions with consumers in debt about ways to effectively manage their circumstances and to ensure they are aware of other organisations that may be able to provide additional support. We think the proposals could be enhanced in certain respects, particularly by encouraging smart meter take-up, which we discuss in further detail in the sections that follow.

Since the initial policy consultation for the DRS, Consumer Scotland has carried out research on energy affordability that provides valuable insight into the prevalence and impact of energy debt in Scotland.[1] Key findings within our research included:

Although current monthly bills are now more affordable (albeit still higher than two years ago) for some households, debt and arrears accumulated during periods of unaffordable bills have become the main source of concern.

The proportion of households that reported they are in energy debt or arrears was 15% (equivalent to 383,000 households in Scotland), an increase from 9% over the last 12 months.

There continue to be particular groups who are more likely to be in energy debt, such as households who receive means-tested benefits, lower household incomes (under £20,000), younger age groups (25-34), households where a member has a disability or health condition, and households with children under 5.

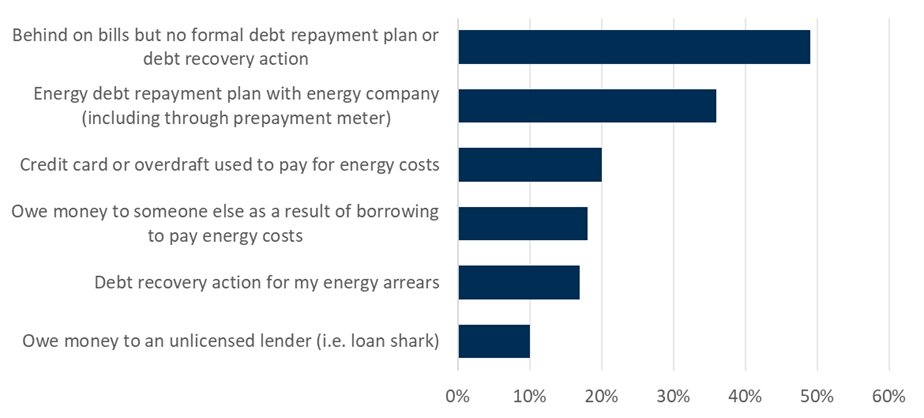

Almost half of customers in energy debt (49%) reported they do not have a formal debt repayment plan in place (see Chart 1 below).

Chart 1

Half of households that are in energy debt are behind on bills but do not have a formal debt repayment plan in place

Source: Consumer Scotland Energy tracker, AFF21: What is the nature of your energy debt or arrears?

These findings clearly illustrate the scale of the challenges that many households currently face. We would also observe that just as energy debt represents a significant challenge for individually affected households, so too has it grown in terms of its impact on consumers generally. Cost allowances under the price cap relating to debt have risen significantly in recent years. Continued growth in these allowances is unlikely to be sustainable. It is critical that, in introducing the DRS, we do not unduly increase the costs borne by consumers generally.

Against this backdrop, Ofgem’s proposals are welcome and timely.

DRS Eligibility

Consumer Scotland generally agrees with the eligibility criteria proposed for the DRS. We consider that these are sufficiently straightforward and clear to allow consumers to access support with relative ease, and for suppliers to readily implement for the first phase of the DRS. The focus on domestic consumers who have held energy crisis debt for multiple years, and who qualify for means-tested benefits, is reasonable in order to deliver some benefit to consumers as quickly as possible.

We also understand the rationale for the suggested phase one criteria that eligible households make some payment towards current usage in the billing period immediately prior to being enrolled on the DRS. We think the phase two criteria are better in this regard, as for some households with significant financial challenges even modest payments towards their energy may be unachievable. But as an expedient measure to enable some benefit to be delivered to some consumers are quickly as possible, we support the initial criteria.

As we expand on later in our response to the “disengaged consumer criteria”, we recommend Ofgem consider how such households can be supported, especially with the use of referrals for holistic debt advice, ensuring the root causes of their debt are tackled, and therefore maximising the opportunity, long-term impact and value of the DRS.

We would also encourage Ofgem to consider how heat network consumers might be supported through the Debt Relief Scheme or an equivalent mechanism. At present, heat network consumers could only access the currently proposed debt relief scheme for any debt accrued on their electricity account (if they are not part of a private wire network). However, this leaves heat network consumers unprotected for any debt accrued on their heating accounts.

This is particularly concerning given that heat network consumers are not protected by the Default Tariff Cap. During the energy crisis, some heat network consumers therefore faced unit rates for heating significantly above those paid by households supplied by a typical gas supplier.

As Ofgem assumes its statutory role as heat networks regulator in 2026, we would welcome further exploration of options to address the position of heat network consumers holding energy crisis related debt.

DWP Data Set

We welcome Ofgem’s decision to use DWP data sources to identify eligible means-tested benefit recipients. As Consumer Scotland highlighted in our previous response to the policy consultation, the initial proposals to use energy supplier-held Warm Home Discount (WHD) data risked otherwise eligible Scottish consumers potentially missing out on debt because of the unique application process for working-age “Broader Group” WHD recipients in Scotland.

We stressed in our response that some Scottish consumers would unfairly miss out on debt relief support because they either had not been advised to apply for WHD previously, or had applied after their energy supplier had used up allocated funds and therefore did not receive the WHD. This process would have contrasted with their counterparts elsewhere in Great Britain who receive WHD automatically and do not risk missing out on the benefit in this manner.

Ofgem’s decisions to now instead use a DWP-held dataset, that does not change the targeting of consumers on means-tested benefits but avoids any structural inequality between Scottish consumers and consumers elsewhere in Great Britain, will ensure the DRS is received equitably across Great Britain.

Engagement Assessment – Smart Meters

By encouraging meaningful engagement, the DRS could play an important role in meeting Ofgem’s goal of improving the culture of debt management. It should help to ensure that consumers do not fall back into debt by tackling the underlying causes of their debt, and in doing so increasing the value for money of the DRS.

Consumer Scotland broadly supports the engagement assessment set out in the technical working paper, though we believe that the implementation of two of the pathways could be improved to ensure meaningful engagement is achieved.

The 3rd engagement criteria, “smart meter installation”, could be improved. Instead, using “agreement to a smart meter installation”, rather than merely a discussion on smart meter installations, would better align with the DRS’ objectives of preventing repeat indebtedness. A discussion alone is unlikely to provide indebted consumers with the help to manage affordability and debt that the installation of a smart meter can provide.

There is evidence that smart meters support affordability and better debt management. UK Government analysis recognises that there are both current consumer benefits, in terms of energy savings from access to up-to-date feedback on usage, and supplier benefits, in terms of savings on operational costs around meter readings, billing and switching,[2] which should also reduce price cap costs for all consumers. Citizens Advice research also found that prepayment customers were more likely to actively seek a smart meter installation because of the additional features they could access and improved support they could get from their supplier.[3] More accurate billing, remote top-ups, early identification of self-disconnection for prepay consumers, and early sight of debt build-up are all obvious consumer benefits of smart meters. These benefits can help those in debt to better manage their situation, and benefit consumers more broadly by reducing the costs of bad debt that have to be recovered through the price cap. Previous UK Government analysis estimated the total value benefit associated with better debt management at approximately £1.1bn.[4]

Encouraging smart meter installs advances both the aims of the DRS and wider smart meter policy goals. Reasonable exemptions should apply where the installation is not reasonably practicable (for example, technical or access constraints), and consumers should still be offered alternative pathways so eligible households that either do not want a smart meter, or are unable to get one, are not excluded.

Engagement Assessment – Signposting and Referrals to Accredited Charities

Ofgem should explore the cost and practicality of warm referrals (for example, live transfers or call backs), where proportionate and appropriate as an improvement to the 4th engagement pathway: “signpost to accredited Advice Charity”.

Warm referrals can provided indebted consumers with holistic advice about energy debt, other priority debts, income and entitlements, and general affordability challenges. This will reduce the risk of debt recurring and/or future affordability challenges, and support the long-term goals and cost-effectiveness of the DRS. We would recommend Ofgem investigate the established infrastructure that already exists between suppliers and select accredited charities for warm transfers and referrals that may be workable at scale.

Supplier Reimbursement Model

Consumer Scotland recognises that the choice of supplier reimbursement model will inevitably create some degree of competitive distortion, given that different approaches will favour suppliers with varying provisioning practices. Suppliers themselves are best placed to assess the detailed impacts, as they hold the necessary commercial data.

However, it remains essential that Ofgem’s decision is framed through a consumer-focused lens, ensuring that the chosen model delivers fair, efficient and proportionate outcomes for all bill payers, who will ultimately fund the DRS.

From a consumer perspective, any reimbursement model must prioritise efficient cost recovery and fairness. In practice this would mean setting safeguards or criteria that do not reward suppliers who adopted low provisioning rates, while ensuring that suppliers who managed debt responsibly are not penalised. This is particularly important as Ofgem has decided that it will undertake its exercise of “netting-off”, or ensuring that suppliers are not being compensated for the same debt twice, at a future point during a bad-debt true up. This makes it important that the DRS reimbursement methodology takes account of bad debt costs already recognised in the price cap. Without this alignment there is a danger that suppliers who did not provision adequately, or who operated with less efficient debt management practices, could be rewarded disproportionately. This would undermine the fairness and efficiency of the scheme, ultimately increase the cost of it to consumers.

3. Endnotes

[1] Consumer Scotland (2025) Insights from Latest Energy Affordability Tracker: Causes and Impact of Energy Debt

[2] Department for Energy and Net Zero (DESNZ) (2024) Smart Metering Implementation Programme Costs and Benefits Report

[3] Citizens Advice (2023) Get Smarter: Ensuring People Benefit from Smart Meters

[4] Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2019) Smart Meter Roll-Out: Cost Benefit-Analysis