1. About Consumer Scotland

Consumer Scotland is the statutory advocacy body for consumers in Scotland. Established by the Consumer Scotland Act 2020, we are independent of government and accountable to the Scottish Parliament. The Act defines consumers as individuals and small businesses that purchase, use or receive products or services. Our purpose is to ensure that markets meet consumers’ needs without causing them unnecessary harm.

2. Key Messages

The world that consumers engage in is evolving rapidly as a result of global economic and political developments, technological change, and broader policy aspirations. This evolution can create positive outcomes and opportunities for consumers where new products, services and markets broaden choice and enhance accessibility.

But it can also create new challenges for consumers where they have to navigate rapidly changing market conditions in established markets, and where they have to navigate uncertainties and unfairness, particularly in new and emerging markets. This provides the backdrop to a challenging agenda for policymakers.

This report

Everyone is a consumer – a user or purchaser of goods and services – in a variety of markets. Taking a consumer perspective is important because it can provide insights into how well markets are working for the consumers who engage in those markets – and the barriers to those who cannot.

This report considers key issues facing consumers in 2024 and beyond, the scale and significance of those issues, and some of the big consumer-related policy questions. The purpose of the report is to help inform wider debate on key consumer issues.

Consumer issues in 2024/25

A broad range of issues affect consumer well-being and their experience of engaging in different markets. These include:

- Price changes during the cost-of-living period have driven changes in patterns of consumer spending and consumption, particularly in relation to essential goods and services. Spending on food and drink across UK consumers for example increased 17% between the first quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2024, but consumption fell by 10%.

- Big rises in energy prices in 2022 and 2023 drove large increases in energy poverty – which now affected around one third of Scottish households. Over one quarter (26%) of households in Scotland in 2024 reported they found it difficult to keep up with their energy bills.

- Around ten percent of Scottish households are in ‘water poverty’ in 2024/25. This is slightly below typical historic rates, as a result of below inflationary increases in the water charge during the cost of living period. But there is a flipside in terms of lower revenues and potentially lower investment in water and sewerage infrastructure.

- One impact of price inflation during the cost-of-living period has been a rise in the number of consumers falling into arrears to their utilities providers. The average amount of arrears for indebted GB household gas accounts almost doubled between 2021 and 2024 for example, whilst around 9% of Scottish households were in energy debt in winter 2024.

- The cost-of-living period was associated with unprecedented inflation inequality – higher inflation experienced by low income households relative to higher income households. This was driven by higher rates of inflation for essential goods and services, and ‘cheapflation’ – higher rates of price increases for poorer quality products than higher quality products, even within narrowly defined product categories.

- Consumer detriment – problems associated with buying or using goods and services which cause consumers stress, cost them money and take up their time – is widespread. The majority (72%) of consumers in Scotland experienced at least one incidence of detriment between April 2020 and April 2021. Detriment incidents problems resulted in a ‘net monetised cost’ to consumers in Scotland of £4.7 billion.

- Poor customer service and complaints handling can create and exacerbate detriment. Consumers dissatisfaction with how complaints are handled is common in telecoms services, whilst being unable to reach their provider is the biggest cause of detriment for consumers in financial services.

- Consumers are more likely to experience detriment when purchasing goods, services and subscriptions online. Practices such as drip-pricing, dynamic-pricing, subscription traps and fake reviews risk causing detriment to consumers.

- Commitments to reach net zero have major implications for consumers. The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) has estimated that over 60% of the required emissions reductions to meet net zero will be “predicated on some kind of individual or societal behavioural change”.

- The majority of consumers (around three quarters) are concerned about climate change. However, they are often unsure what they can do to support the transition to net zero, and would like to see more leadership from governments, regulators and business.

- Policy aspirations to decarbonise homes and transition away from petrol and diesel cars in favour of electric vehicles have the potential to bring benefits to consumers and wider society, but also bring significant risks and potential costs for consumers. For example, home charging for electric vehicles is associated with cheaper costs and higher convenience, but around half of all households in Scotland live in circumstances where charging at home is not likely to be an option. This situation risks seriously curtailing the uptake and use of EVs, and creating inequalities in the use of this technology, unless substantial enhancements to the public charging network are made.

Supporting consumers in a changing world

Policy has to develop proactively in order to create and maintain a framework to support consumers to navigate complex markets, mitigate consumer detriment and unfair outcomes, and ensure consumers can play an active role in supporting the transition to net zero.

These issues provide a challenging agenda for governments, regulators and policymakers. Key policy challenges include:

- Designing tariff structures – and targeted affordability support – for essential services in order that the substantial investment requirements to sustain those services is shared fairly across consumers.

- Updating regulation and enforcement in relation to new products, platforms and services to protect consumers from the risks of new harms as they emerge.

- Ensuring consumers have access to adequate information and advice to engage confidently in markets.

- Playing a more proactive leadership role in supporting consumers to be able to play an active part in the transition to a net zero society, through a mixture of advice and information, financial incentives, and protection against harms.

3. Consumer Outlook 2024

Introduction

2024 is a time of opportunity and challenge for consumers. Inflation has fallen as dramatically as it rose, but it leaves a legacy of higher prices. In many markets consumers have abundant choice but they can be exposed to detriment from poor quality goods and services and lack of transparency around prices and terms. New products and technologies create new opportunities but also risks for consumers where markets are developing.

The word ‘consumer’ can mean different things to different people. For Consumer Scotland, people and small businesses are consumers whenever they purchase or use any goods or services, whether provided by private or public sectors (Box 1).

The consumer perspective matters because it can provide important insights into how well markets are working for the consumers who engage in those markets, and the barriers to engagement for those who cannot. It also gives insight into how markets can be made to work better and services delivered more effectively.

This report considers key issues facing consumers in 2024, and the big consumer-related policy issues facing policymakers. These include:

- How should we distribute the costs of essential services fairly, not just between consumers today but between current and future consumers?

- How can consumers be supported to make the changes to their lives that will be necessary to realise ambitious net zero targets?

- How can consumers most effectively be protected from detriment, including from detriment associated with new technologies and platforms?

The purpose of this report is to set out the scale and significance of some of these big consumer-related policy challenges. It aims to bring focus to the key issues, in order to help inform debate amongst the, public, media, government, regulators, other public bodies, politicians and business. The report is not intended to be definitive of all consumer issues in all markets, but to highlight some of the most significant consumer issues at the forefront of current policy debate.

Who are consumers? |

|

The word ‘consumer’ can mean different things to different people. For Consumer Scotland, the word ‘consumer’ is interpreted broadly. Our founding legislation defines a consumer as being any individual or small business who purchases, uses or receives goods or services.[1] In this sense, everyone in Scotland is a consumer in a wide variety of contexts. We are consumers not just when we go shopping to buy physical things, but also when we use private and publicly provided services. Passengers, tenants, internet users, energy users, students and patients are all consumers. People might not label themselves as a consumer in these contexts. But the benefit of viewing such a wide range of people as consumers is that it helps to recognise that, when people use goods and services, they are in a particular kind of relationship with those who provide those goods and services. Our legislation also defines consumers to include potential consumers. This includes- those who don’t use a service at present but might need to use it in the future, or who should have access to it, but for some reason do not. Potential consumers also include future generations of consumers. The Consumer Scotland Act also defines consumers to include small businesses (those employing fewer than 50 people) when those businesses are purchasing or using goods or services. Taking a consumer perspective can influence the nature of how we think of the relationship with organisations that provide those goods and services. It recognises the potential for power imbalances and conflicting interests between providers and consumers. And by including potential future users of a service as consumers, it enables us to consider whether there are barriers that unfairly exclude some people from those services. |

Households are spending more on essentials, but getting less in return

Measured purely in terms of inflation, the ‘cost of living’ crisis of 2022 and 2023 appears largely to be over. The CPI measure of price inflation had fallen to 3.1% in the year to July 2024, having declined from 11.1% in October 2022. But it would be wrong to assume that cost of living challenges have gone away simply because inflation has fallen. Whilst inflation has fallen, price levels of most essential goods and services remain well above pre-crisis levels.

Take groceries for example. The price of a typical basket of food and non-alcoholic beverages in March 2024 was 31% higher than it was in March 2021. Energy prices were 42% higher in March 2024 than in March 2021, comfortably outstripping earnings growth.[2]

Consumers respond to these price changes in a variety of different ways. They may change how much they consume, and their pattern of consumption across different categories of goods and services.

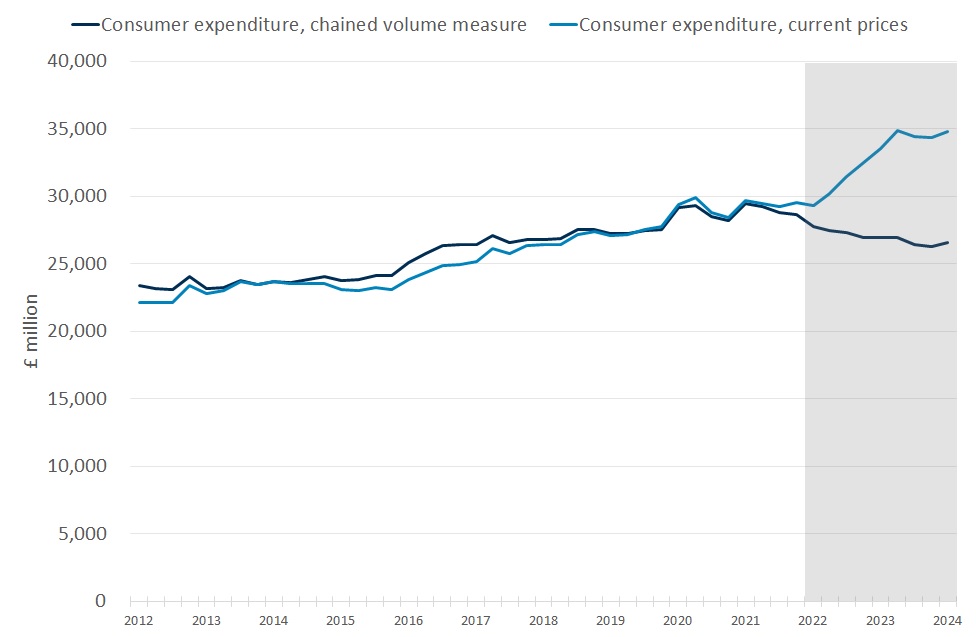

An example of these changes can be seen by looking at changes in spending on, and consumption of, food and (non-alcoholic) drink. Chart 1 compares two measures of aggregate consumer expenditure:

- Price measures of spending, i.e. total value of spending on particular goods and services; and

- Volume measures of spending, which measure the amount of a good or service that is purchased, having controlled for changes in the price or quality of that item.

On the price measure of expenditure, UK household food spending increased by 17% between Q1 2021 and Q1 2024. In contrast, the volume measure of expenditure (known as Chained Volume Measure, or CVM) on food fell by 10% over the same period. The implication is that households are consuming less food or switching to food of lower quality, while spending more in cash terms.[3]

A similar picture emerges when looking at patterns of consumer expenditure on energy. Over the same period, household expenditure on energy in price terms rose 47%, but it declined by 6% on a Chained Volume Measure.

Chart 1: Household spending on food has increased substantially, whilst food consumption has fallen

Household expenditure on food and non-alcoholic beverages, UK

Source: Consumer trends from the Office for National Statistics Consumer trends, UK - Office for National Statistics

More consumers are falling behind with utility bills

As well as changing their patterns of consumption across different goods and services, consumers might also respond to a cost of living crisis by increasing-their total spending by saving less or borrowing more.

However there is little evidence that households have responded to the cost-of-living crisis by saving less. The household saving ratio actually increased during the cost-of-living crisis, from 7.9% in Q1 2022 to 11.1% in Q1 2024.[4]

However, whilst aggregate savings may have increased, there is evidence that a growing number of households are falling behind on priority bills such as energy, water and council tax:

- Across Great Britain as a whole, the number of households in arrears with their energy bills increased significantly during the cost of living crisis, whilst at the same time the average amount by which those households were in arrears also increased. The number of electricity and gas accounts in arrears reached 964,000 and 749,000 respectively in Q1 2024, a reduction from the peak of the crisis period, but well above pre-crisis records. The average amount of arrears increased between Q1 2022 and Q1 2024 from £687 – £1,264 per household for gas and from £852 - £1,452 electricity.[5]

- Consumer Scotland’s own energy tracker found that 9% of Scottish households were in energy debt in winter 2023/24.[6] This figure includes people who have borrowed from friends or family or taken out loans to pay for their energy bills, as well as those in arrears with their energy supplier.

- Scottish Water data indicates that the number of households behind with water bills exceeded 350,000 in 2021/22, a record high, with average debt of £140 per household.[7]

- In telecoms, arrears appear to be a somewhat less significant problem. Across the UK, just over 2% of fixed and mobile telecoms users had missed at least one payment in 2023, with little evidence that the prevalence of arrears increased during the cost of living crisis.[8] However, telecoms users are increasingly likely to cancel or reduce their use of services, and reduce spend elsewhere, due to affordability issues.[9]

Increases in consumers’ debt and arrears with utilities providers raises important policy questions. These include:

- How consumers can be supported to repay debt and arrears; where debts cannot be recovered

- How those costs are ‘socialised’ across other existing and future consumers; and

- How charges and tariffs – together with affordability support – can be more effectively designed to limit the risks of consumers falling behind with their payments.

Some of these issues are picked up in subsequent sections of this report.

The cost of living crisis has disproportionately affected low-income households

The data presented so far on prices, consumption and debt has been at an aggregate (economy-wide) level. But the cost-of-living crisis is unlikely to have been experienced equally by different groups of consumers.

One reason for this is that households consume different baskets of goods and services. Because price rises varied significantly across different categories of goods and services, some groups of households were exposed to faster rates of inflation than others.

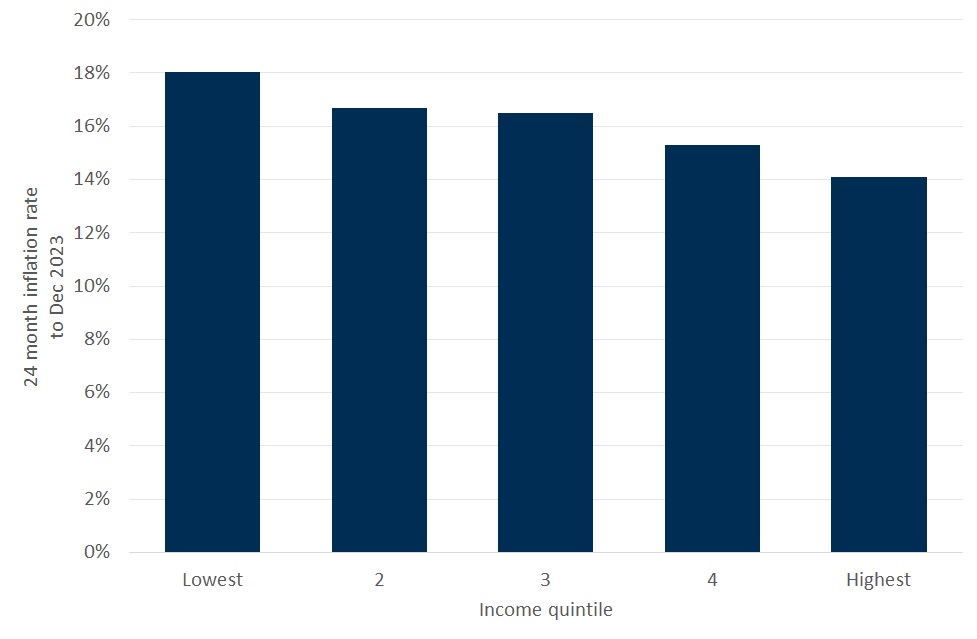

In particular, the rapid price rises associated with ‘essential’ categories of spending such as energy and food exposed low income households to a faster rate of inflation than other households, given that a larger proportion of their total spending is on these categories. Chart 2 shows that, for much of the cost-of-living crisis period, the lowest income households in Scotland faced a higher rate of effective inflation than higher income households.

In fact, there are grounds for saying that Chart 2 is likely to underestimate the extent to which low-income households were disproportionately affected by the cost-of-living crisis. This is because it only considers patterns of spending across broad categories of goods and services – but not different patterns of spending within specific product categories.

Research by the IFS shows that, within individual categories of groceries, lower quality products (where quality is inferred by the unit price) experienced systematically larger price increases from 2021 to 2023 than higher quality products.[10] The IFS argues that this so-called ‘cheapflation’ results in ‘inflation inequality’ which in turn drove inequality in the cost of maintaining a fixed standard of living during the cost-of-living period.

Chart 2: Lower income households have experienced a higher level of overall inflation than higher income households over the last two years

Estimated inflation by income quintile for the 24 months to December 2023 – Scotland

Source: Consumer Scotland analysis of the Living Costs and Food Survey (ONS)

Note: Figures are based on data from 2019-20 and 2021-22, missing out 2020-21 due to the impact of the response to the coronavirus pandemic.

Charges and tariff structures for essential services have to balance investment needs with bill affordability

The cost of living crisis refocussed attention on the affordability of essential services, like energy, water, telecommunications and housing.

The big picture in many of these markets is how to strike the right balance between, on the one hand, the need to raise sufficient revenue from consumer charges to invest in critical infrastructure, and on the other hand, the need to ensure that those charges are fairly distributed and are affordable for consumers – particularly those on low incomes and/ those in vulnerable circumstances (see Box 2 for a discussion of the interpretation of consumers in vulnerable circumstances).

Getting this balance right is becoming increasingly challenging in several markets – notably energy and water – where increasing levels of investment are required to fund the upgrading of infrastructure needed to support the transition to net zero.

Getting the balance right is partly a question of the level at which consumer prices and charges are set. But it’s also a question of tariff policy more generally – whether consumers are charged according to how much of a service they use, and the extent to which affordability interventions provide tailored support for consumers in particular circumstances.

What are the characteristics of consumers in vulnerable circumstances? |

|

The Consumer Scotland Act defines vulnerable consumers as consumers who, by reason of their circumstances or characteristics—

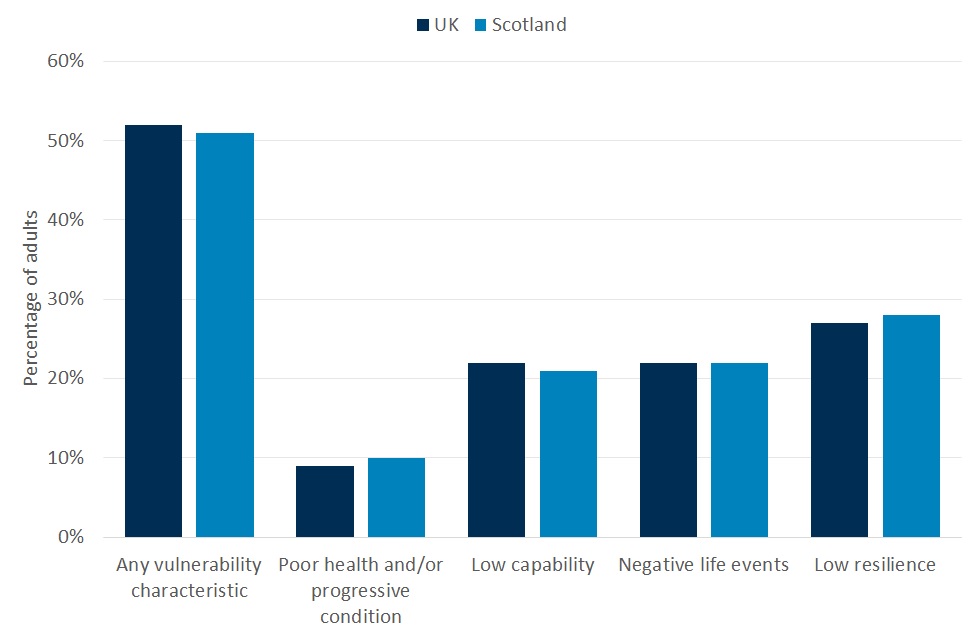

Consumer vulnerability is not a binary outcome that can be defined by one or more characteristics. A consumer can be at greater or lesser risk of vulnerability in different markets at any one time. Because vulnerability is conceptualised as a spectrum of risk, rather than a binary outcome, it isn’t sensible to try to quantify the number of consumers in vulnerable circumstances. But it is possible to consider the number of consumers who have experienced one or more of the drivers of vulnerability. For example, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has undertaken work to quantify the prevalence of the drivers of vulnerability. It identifies four main drivers of vulnerability.[11] A consumer is deemed to be at greater risk of vulnerability the greater the number of risk factors they have experienced during the past 12 months in relation to:

FCA analysis from 2022 indicates that 10% of adults in Scotland have health related vulnerability characteristics, one fifth have low capability or have experienced negative life events in the past year; and around a quarter have low financial resilience (Chart 3). The same analysis shows that, in 2022, half of adults in Scotland displayed one or more characteristic of vulnerability, with 15% showing risk factors in at least two domains, and 5% showing vulnerability characteristics in at least three domains. Findings for 2024 will be published later this year. The proportion of adults showing different vulnerability risk factors was consistently very similar in Scotland as in the UK as a whole. |

Chart 3: The prevalence of the characteristics of vulnerability is similar in Scotland to the UK

Proportion of adults in Scotland showing various characteristics of vulnerability

Source: Consumer Scotland analysis of FCA’s Financial Lives Survey 2022 Financial Lives 2022 survey | FCA.

Balancing affordability, fairness and investment needs in energy tariffs

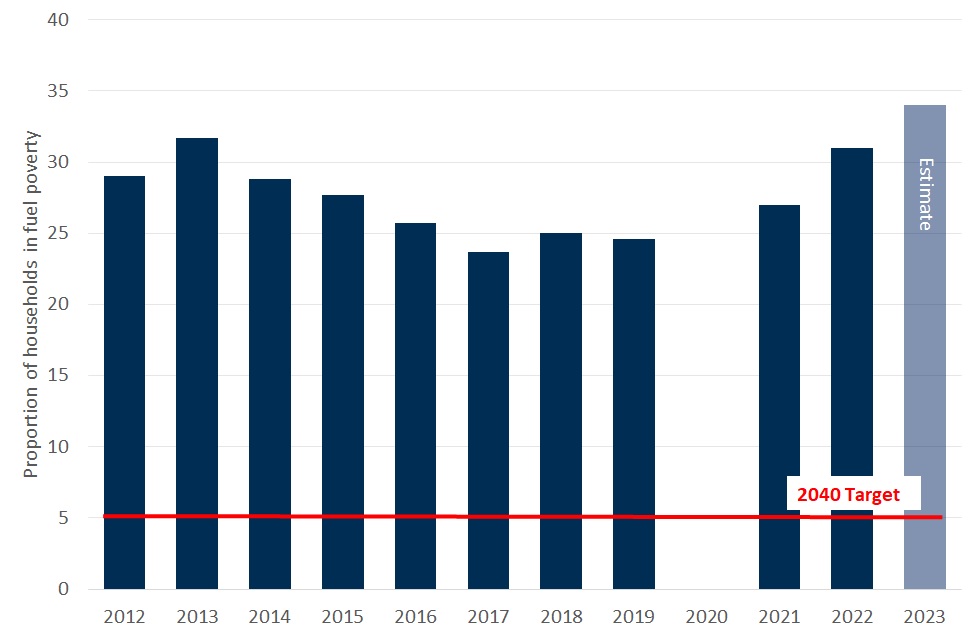

The substantial energy price increases during 2022 and 2023 brought the question of energy affordability to the forefront of public debate. Substantial temporary measures were put in place to mitigate the impacts of price increases on households. Nonetheless, fuel poverty rates increased (Chart 4), and levels of energy debt surged. Consumer Scotland research found that 26% of households found it difficult to keep up with their energy bills in winter 2024, with almost one in ten (9%) in energy debt.[12]

Chart 4: The proportion of households in fuel poverty increased in 2022

Proportion of households in Scotland in Fuel Poverty

Source: Scottish House Conditions Survey, various years; 2023 estimate is from the Fuel Poverty Advisory Panel.

Affordability support in the energy market has now largely returned to the pre-crisis policy. But whilst energy prices have fallen from their peak, they remain substantially elevated on pre-crisis levels.

In structuring energy tariffs and the design of energy affordability policy, the underlying issue is how to adequately balance the need to support the investment required to ensure the energy system remains resilient, whilst ensuring that energy charges are affordable for consumers.

There is an ongoing debate around how to get this balance right. Part of that debate has focussed on whether or not there should be a redistribution of charges from the standing (or daily) charge to the volumetric charge (or unit rate).[13] Recent large increases in the standing charge, particularly for electricity (the standing charge doubled between 2022 and 2023) are often perceived to be unfair. They limit the extent to which consumers can influence their bills by reducing their energy use, and they implicitly levy a higher average price per unit of energy on lower rather than higher users.

However, eliminating the standing charge and reallocating it to the variable rate may not in itself represent an equitable way of sharing the substantial, system wide costs associated with maintaining and developing the network across consumers. The system-wide fixed costs are likely to become more significant, as renewables become a larger part of the energy mix. Thus whilst shifting part of standing charges to the unit rate would be somewhat progressive (benefit low income consumers proportionately more than high income consumers), and provide consumers with more control over their bills, it would also create significant numbers of ‘losers’ – groups whose bills would increase. Significantly, this group would include those with high essential energy needs, including in particular some disabled consumers.

The debate about energy affordability needs to move beyond the standing charge issue to identify meaningful and implementable affordability policy, to address the underpinning principle of fairness. Current approaches to energy affordability are complex, and not targeted as well as they could be . None of the energy affordability policies available in Scotland take into account households energy needs, and the only policy that provides bill discounts is subject to complex qualification criteria and an onus on consumers to apply to the suppliers to access (Box 3).

Developing a more adequate energy affordability policy won’t necessarily be easy. Many of the challenges are practical, in that there are limited sources of data simultaneously on households financial circumstances and their energy need that can form the basis for targeting affordability support. But there are also conceptual challenges to consider too. For example, the consideration of how affordability policy should work alongside the emergence of new tariffs that allow energy prices to become more sensitive to demand at different times of day.

These challenges notwithstanding, a focus for policy makers should be to modernise energy affordability policy as a matter of priority.

Energy affordability policy in Scotland |

|

A number of different energy affordability policies currently operate in Scotland. By energy affordability policies, we mean policies that provide a discount on energy bills, or social security payments explicitly labelled as being to support payment of energy bills (even if no strings are attached to how those are used). These policies include:

|

Water charges increased less rapidly than they might have done, helping keep bills affordable but reducing revenue for investment

Under the arrangements for setting domestic water charges in Scotland, the large and unexpected increases in inflation that occurred in 2022 and 2023 might have been expected to result in large increases in those charges. However, the response of Scottish Water was to increase charges by less than technically would have been permissible.

Specifically, charges were increased by 4.2% and 5% in April 2022 and April 2023, when they could have been increased by 6.2% and 13.1% in those years if Scottish Water had implemented the CPI+2% basis for annual charge increases that it is permitted to. There was some ‘catch-up’ in April 2024, when charges increased by 8.8%, significantly more than the relevant inflation figure of 4.6%.

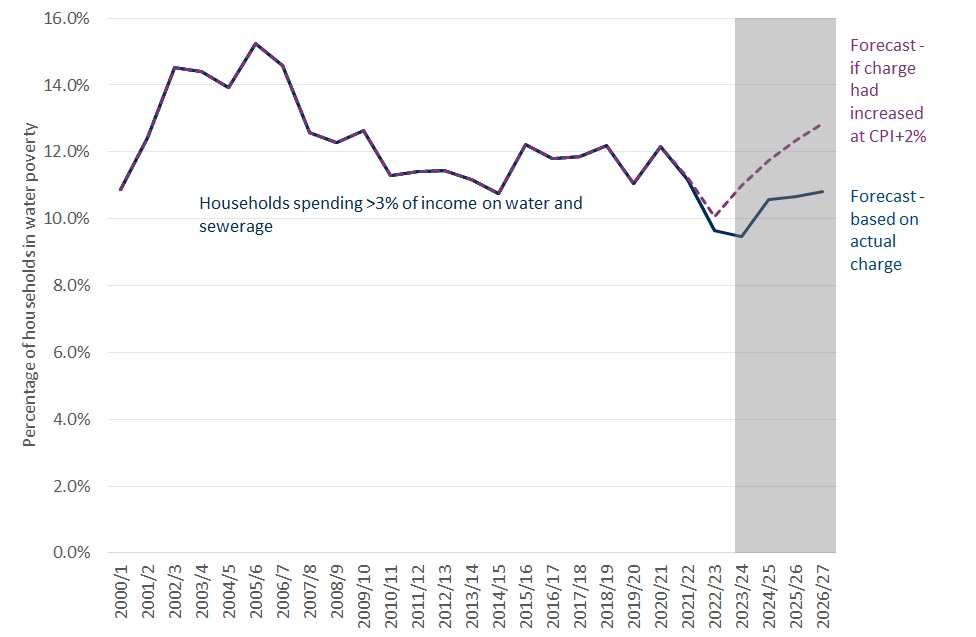

The lower than anticipated increase in charges has helped those charges remain affordable for many consumers. Consumer Scotland’s analysis indicates that there has been no significant increase in water poverty – a key measure of the affordability of water charges – during the cost of living crisis itself. Had water charges increased by CPI+2% during the cost of living crisis, an additional 40,000 households in Scotland would be in water poverty (Chart 5).

But the flipside to lower than permissible increases in the water charge is that Scottish Water has raised less revenue than it otherwise would have done to fund investment in the water and sewerage network. Our analysis suggests that the lower than permitted increases in the charge will reduce Scottish Water revenues by around £90m in both 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 and will continue to have an impact on revenues in future years.

As planning begins for the next Strategic Review of Charges period, which will cover 2027/2028 – 2032/2033, serious consideration needs to be given to the balance between investment and consumer charges.

Chart 5: Lower than permissible increases in water charges have resulted in lower rates of water poverty, but reduced levels of charges for investment

Proportion of households in Scotland spending more than 3% of net AHC equivalised income under two scenarios for the water charge

Source: Consumer Scotland analysis of DWP’s Households Below Average Income dataset, using the IPPR tax-benefit model.

Most purchases do not cause consumers problems; but the value of consumer detriment is nonetheless substantial

So far, this report has largely considered the prices and charges paid for goods and services. But the set of issues that consumers face is much wider than this. In particular, the quality and safety of goods and services matters, as does the response of the providers of those goods and services when things go wrong.

Sometimes, goods or services don’t live up to consumers’ expectations. They might be of lower quality than expected, unsuited to the purpose intended, or associated with unclear or misleading prices, terms or conditions. In some circumstances, goods can be unsafe, in breach of consumer law, or supplied fraudulently. And sometimes, it can be difficult to change or cancel services, or make complaints.

Problems like this can cause detriment to consumers. This detriment can cause consumers stress, cost them money and take up their time.

The UK-wide Consumer Protection Study (CPS) 2022 found that most purchases did not result in problems, and most problems were resolved to the satisfaction of consumers.[14] It also found that most detriment incidences were associated with relatively small cost.

At the same time however, detriment is commonly experienced by consumers. The CPS estimated that 72% of consumers in Scotland experienced at least one incidence of detriment between April 2020 and April 2021. In total, there were 18.6 million detriment incidents in Scotland in that year, and these problems resulted in a ‘net monetised cost’[15] to consumers in Scotland of £4.7 billion. The median ‘net monetised detriment’ per individual incident of detriment was £28 in Scotland, which was broadly similar to other parts of the UK.

The 2024 iteration of the Consumer Protection Survey is due to be published by the CMA later this year.

Consumer detriment is more likely to be experienced in some sectors than others

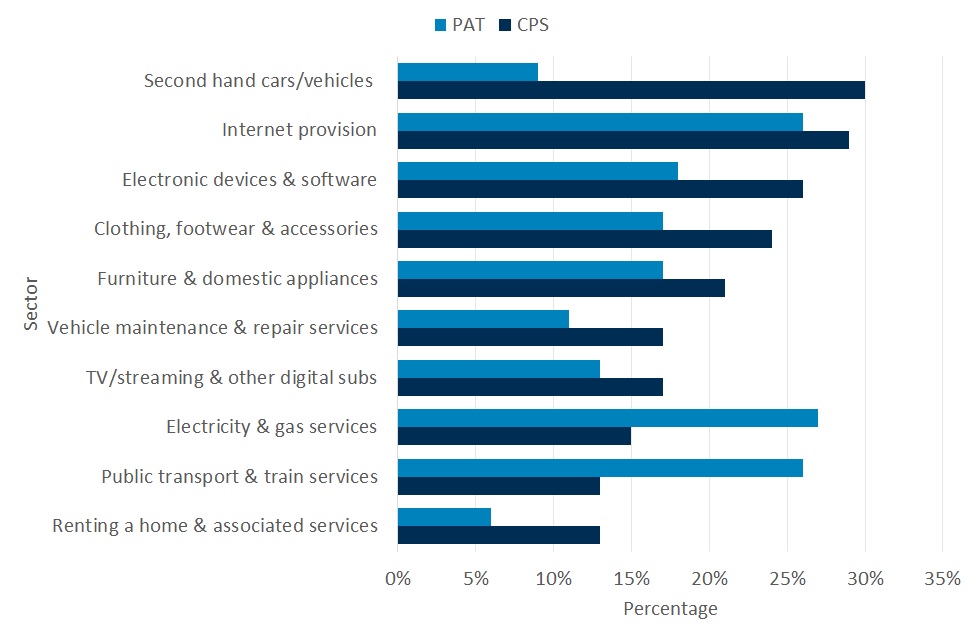

Evidence suggests that detriment varies by sector, changes over time and is shaped by the wider economic/social context.[16]

- The 2022 CPS suggested that ‘second hand cars/vehicles’ was the leading sector in both the UK as a whole (30%) and Scotland (35%) in terms of the proportion of consumers who purchased a product in this sector and experienced detriment (Chart 6). This sector was followed by ‘internet provision’ services (27% in Scotland and 29% in the UK) and ‘electronic devices and software’ (26% in both Scotland and the UK).

- A separate study, the 2023 Public Attitudes Tracker found high levels of detriment associated with ‘electricity and gas services’ and ‘public transport and train services’. This could have been driven by the cost-of-living crisis, which saw rail strikes and rapidly rising energy costs. The latter resulted in a rapid rise in customer engagements with their energy suppliers, which suppliers were, initially at least, not always well prepared to respond to.[17]

It is worth noting that there is substantial variance in the ‘cost’ of detriment between sectors. For example, the CPS estimated that for the UK as a whole, the median ‘net monetised detriment’ was £463 for individual detriment incidents in the ‘second hand cars and vehicles’ sector but £55 in the ‘internet provision’ services sector and £28 for ‘electricity and gas’ services. The rented housing sector accounted for the highest level of net monetised detriment (£7.4 billion UK-wide), with 17% of rental agreements resulting in some form of consumer detriment.

Chart 6: detriment occurs in a variety of different sectors and varies over time and between different surveys

The 10 leading detriment sectors in terms of the proportion of CPS participants who purchased goods or services/subscriptions in certain sectors and experienced detriment, compared with results from the PAT.

Sources: Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy – Consumer Protection Study 2022; Department for Energy Security & Net Zero - Public Attitudes Tracker: Consumer Issues - Spring 2023

Note - chart strips out sectors from the CPS (e.g. ‘airline services’, ‘package holidays/tours’) in which detriment incidents were thought to be significantly skewed by COVID lockdowns/restrictions

Poor customer service can create and exacerbate detriment. Complaints handling is consistently one of the three key drivers of complaints relating to both broadband services and monthly mobile phone contracts. This is also underlined in the financial sector, where the number one issue relating to detriment amongst adults with financial products was being unable to reach their provider (14%).[18]

The July 2024 UK Customer Satisfaction Index by the Institute of Customer Service found that satisfaction levels are at their lowest level since 2010, with consumers reporting particularly low levels of satisfaction in relation to complaints handling.[19] One potential explanation for a decline in customer satisfaction – with how complaints are handled in particular – is that there has been an increase in the number and complexity of complaints during the cost-of-living crisis. However, declining customer satisfaction is a longer term trend, reflecting in part the way that some businesses have increasingly introduced barriers to customers being able to contact them with issues or complaints.

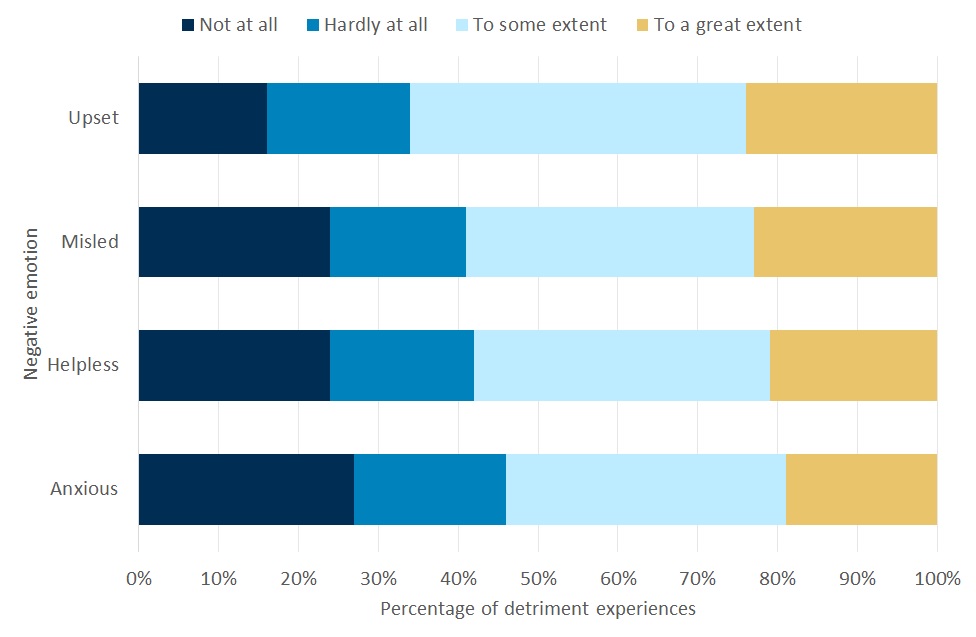

Detriment causes financial and emotional harm to consumers

Detriment can affect consumers financially. But detriment incidents can also have a negative impact on emotional wellbeing and physical/mental health. Chart 7 shows the proportion of detriment incidents that led to survey respondents feeling ‘anxious’, ‘helpless’, ‘misled’ or ‘upset’. Over half of the detriment incidents were associated with one of these feelings or emotions.

The CPS found that a number of consumer characteristics were associated with an increased risk of experiencing detriment. These included:

- Worse self-assessed financial condition

- Being younger

- Being of an ethnicity other than white British

These groups may be more likely to experience detriment either because their resource constraints mean they have less choice or because they more frequently need to compromise quality for price.

Concerningly, the groups most likely to experience detriment are often the same groups that experience the worst impacts from detriment, both in terms of monetised detriment and wellbeing. They are also the least likely to take action in response, compounding the initial harm experienced.

Chart 7: detriment can have a negative impact on the emotional wellbeing of many consumers

Proportion of detriment incidents that led to CPS participants experiencing negative emotions

Source: Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy – Consumer Protection Study 2022

Online platforms bring benefits to consumers but might also expose them to greater detriment

The CPS found that consumers are somewhat more likely to experience detriment when purchasing goods, services and subscriptions online.

There is a risk that the shift to online purchases and developments in use of Artificial Intelligence – which potentially allow firms to adopt more sophisticated pricing, signposting and influencing methods – might expose consumers to the risk of experiencing higher detriment.

Practices that could become more prevalent as online purchases and use of artificial intelligence become more ubiquitous, and which could pose risks to consumers, include:

- Drip pricing. This occurs when consumers are shown an initial price for a product and additional fees are introduced (or “dripped”) as consumers proceed with a purchase or transaction. Drip pricing can undermine price transparency and make it difficult for consumers to make informed purchase decisions based on price and/or the characteristics of the product.

- Dynamic pricing is the process whereby businesses flex their prices for a service over time in response to changes in supply and demand. Dynamic pricing has been fairly ubiquitous in the travel industry for some time, and consumers are used to seeing the prices of flight tickets or hotel bookings change from one day (or even hour) to the next.

- Fake reviews which exploit consumers understandable desire to learn from the experiences of others.

- Subscription traps use a free or discounted trial period for a product or service as a way of luring consumers to sign-up to a longer, higher-cost subscription. Unclear terms mean that consumers can often be unaware that they have started paying a higher charge for the service, and even once they do become aware, can often find that the process of unsubscribing from the service is much more onerous than the process of signing up in the first place.

Some of these practices are not necessarily always bad news for consumers. Dynamic pricing may enable firms to offer greater discounts during period of low demand, providing greater choice and making some products and services available to consumers who wouldn’t have been able to afford them if a flat price was offered. The risk is that this potential benefit will be offset by a loss of consumer welfare in aggregate terms, with consumers on balance paying more, and businesses benefiting from increased turnover. A majority of consumers say that they are opposed to the principle of dynamic pricing[20].

Fake reviews on the other hand are unambiguously negative. Reviews play an essential role in online shopping, providing valuable insights and social proof that can help consumers make more informed decisions. 9 out of 10 UK consumers report reading reviews[21], so reviews that are misleading can contribute to significant detriment.

Consumers are generally antagonised by dripped pricing, although they are becoming grudgingly used to it. UK-wide research in 2023 found that drip pricing is a common strategy used by online traders in the transport and communication, hospitality, and entertainment sectors[22].

An element of ‘dripping’ is arguably inevitable – and not necessarily harmful – where it reflects genuine consumer options for the nature of the service offered. But dripped fees are more likely to cause detriment to consumers if some or all of the following conditions hold: the dripped fee is for a mandatory part of the service; the value of the dripped fee is high relative to the base price; dripped fees are presented as ‘optional’ but are automatically added to the checkout; they are dripped more than halfway through the checkout process; and where the checkout process identifies more than three dripped fees.

Research by Alma Economics found that the use of harmful dripped fees was particularly prevalent in the transport and entertainment sectors, where 32% and 37% of providers respectively used three or more harmful forms of drip pricing (Chart 8). The research found that dripped fees cause UK consumers to spend between £595 million to £3.5 billion extra online each year than they would have done without dripped fees.

Online platforms are one example of the ways that new products or technologies can create risk of detriment to consumers, but there are other examples. The transition from traditional analogue phone lines to Voice Over Internet Protocol (VOIP) technologies creates risk of harm to a minority of (mainly older, rurally based) consumers.[23]

Chart 8: A significant proportion of providers make use of drip-pricing, including harmful drip-pricing techniques

Proportion of sampled providers in each sector using dripped fees, and percentage of providers with three or more instances of harmful dripped fees

Source: Alma Economics (2023) Estimating the prevalence and impact of online drip pricing (publishing.service.gov.uk)

Consumer law and regulation plays an important role in protecting consumers from detriment and helping them to resolve problems

A strong legal and regulatory framework is critical for protecting consumers from harm and ensuring markets work well for consumers. Consumer law and regulation can protect consumers from unjustified or unclear product claims, for example in relation to products’ environmental credentials (greenwashing), or from unsafe products.

Consumer law and regulation can also protect consumers from unfair practices. For example, the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers (DMCC) Act 2024 introduces protections against various online practices and should enable the CMA to take swifter enforcement action in certain cases (Box 4). Another example is the prohibiting of telecoms companies from including inflation-linked or percentage-based price rise terms in new contracts. [24]

The regulatory framework that applies in a market also influences wider questions about how markets work for consumers, in particular in relation to what happens when consumers feel that they have received unsatisfactory services from a particular firm – who can they complain to and what confidence can they have that those complaints are taken seriously.

The form and structure of regulation is a live question in several markets. In legal services for example, the Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill is currently being considered by the Scottish Parliament.[25] The Bill sets out a new regulatory system and will impact on the way legal services are provided to consumers, and the way in which they can complain if they are unhappy with the services they receive. It aims to make complaints processes simpler and more consumer friendly. During the passage of the Bill, Consumer Scotland has recommended improvements to monitoring, accountability, governance and transparency in order to increase consumer confidence in the legal system. We specifically advocated for improved oversight arrangements, informed by consumer views, to determine whether the regulatory system was meeting its objectives or not.[26]

Good regulation should be based on a genuine understanding of consumers’ experiences and behaviours. And it needs to adapt continually in response to the evolution of technologies, products and practices to ensure that consumers are adequately protected from detriment and that markets work effectively and fairly for consumers.

Protecting consumers from harm – the DMCC Act 2024 |

|

Changes introduced as part of the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024 will provide the CMA with new direct consumer enforcement powers. When these powers come into effect, for the first time the CMA will be able to decide whether key consumer laws have been broken rather than taking a case to court. If it finds a consumer law breach, the CMA will be able to impose remedies, which may include requiring firms to offer compensation or other redress for consumers. These changes don’t change consumer law, but should enhance the ability of the CMA to take swift action, enhancing consumer outcomes at a strategic level. Additionally, changes introduced as part of the DMCC Act will strengthen existing UK consumer law to mitigate the risk of consumer detriment arising from some of the online platforms and practices noted above. Specifically, it introduces a number of new provisions to mitigate consumer detriment in relation to fake reviews, drip pricing and subscription traps.

|

Consumers are at the heart of the transition to net zero

It is not just new technologies that create opportunities and risks for consumers – broader political and societal goals can also accelerate the development of new markets and products, associated with different choices and uncertainties. The Scottish Government’s commitment to achieving net zero emissions by 2045 in Scotland is a key realisation of this.

The transition to net zero will be the defining policy challenge of the next two decades. The public, in their role as consumers, have a critical part to play in ensuring that targets are met. The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) has estimated that over 60% of the required emissions reductions to meet net zero will be “predicated on some kind of individual or societal behavioural change”. [27]

What we consume, how we consume, when and where we consume – these are all decisions that influence progress towards targets. The requirement for behavioural change is seen across a range of markets, including:

- Home heating – including measures to improve the energy efficiency of homes, and to adopt low or zero carbon heating systems, such as heat pumps or renewable technology.

- Transport – through the adoption of electric vehicles, combined with greater use of active travel and public transport.

- Water – using less water and appropriately disposing of household waste to help mitigate the impacts of climate change on issues relating to drought, scarcity, quality and flooding.

- More sustainable consumption practices in a range of consumer markets including food, leisure and clothing.

Consumer Scotland research shows that the majority of consumers (around three quarters) are concerned about climate change, a finding that is consistent with other surveys[28]. However, consumers are not always sure what they can or should do to support the transition to net zero, and want to see more leadership from governments, regulators and industry.

Even where consumers are concerned about climate issues – and make ‘sustainable’ consumption choices – forthcoming Consumer Scotland research shows that their purchasing behaviours are often driven by considerations of cost, convenience and choice as much as by underlying environmental attitudes. This observation has implications for the design of policy to support the transition.

For example, whilst the Scottish Government’s Circular Economy Strategy, and the Circular Economy Bill currently before the Scottish Parliament, aim to promote the re-use and repair of goods already purchased, consumers are likely to need more support to change their behaviour. This may include changing the design of goods, expanding the market for second-hand goods and providing better information to consumers.[29]

There is a significant onus on consumers to decarbonise their home heating

Some of the most significant challenges to consumers as a result of the transition to net zero will come in relation to changes to the way that we heat our homes and places of work.

The Scottish Government’s consultation on a draft Heat in Buildings Bill proposes the establishment of new minimum standards of energy efficiency to be met in every home that uses fossil fuel heating by 1 January 2034, and that all homes and businesses in Scotland will be required to discontinue their use of fossil fuel heating systems no later than 1 January 2046.

These targets, if enacted, put a significant onus on consumers to better insulate their homes, and adopt low carbon technologies such as solar panels and heat pumps.

This is a big ask of most consumers. It will imply significant upfront costs and potentially disruption for a large number of households in upgrading insultation and adopting low carbon technologies such as heat pumps and solar panels (with potential for longer term benefits). It also requires consumers to engage in relatively nascent markets, where lack of information, underdeveloped standards and certification schemes, and the potential for poor quality installation are real risks.

Barriers to consumer engagement in the market for home energy efficiency products are likely to include:

- Limited capacity of advice organisations to provide appropriately tailored advice about which low carbon technologies are necessary and/or appropriate for their homes – and limited current knowledge about the role that heat networks might play for some households[30].

- Significant upfront costs of many energy efficiency projects, combined with longer term and uncertain financial payback periods.

- A confusing array of standards and certification bodies.

- Substantial disruption to homes during the installation of some energy efficiency technologies.

- The risk of experiencing poor quality work or being exposed to scams – with significant resource constraints of enforcement bodies such as trading standards in being able to clamp down on scams and rogue traders[31].

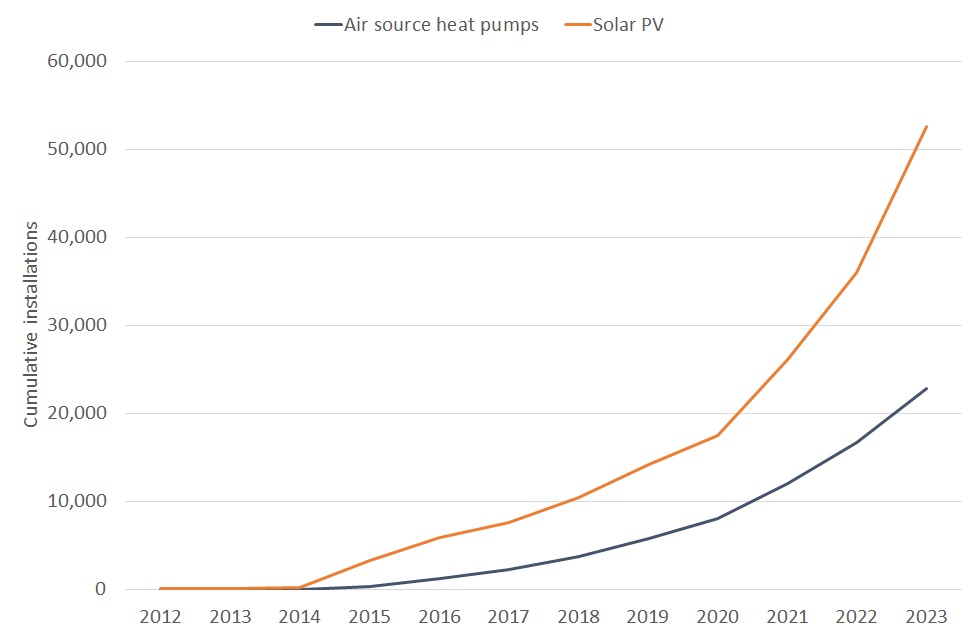

In this context – as is often the case in emerging markets – it is unsurprising that adoption of some low carbon technologies remains low. Taking air-source heat pumps and solar panels – as two examples of low carbon technologies that will need to see widespread adoption in coming years – chart 9 shows that the number of homes installing these technologies in Scotland remains low, albeit having shown a rapid increase in recent years.

The requirement to decarbonise homes undoubtedly has the potential to bring benefits to consumers and wider society, but it also brings significant risks and potential costs for consumers. Policymakers and regulators need to give careful consideration to how they can help consumers access the advice and support they will need to engage confidently in the market for low-carbon heating.[32]

Chart 9: Installations of renewable technologies are increasing

Number of cumulative MCS registered installations of Air Source Heat Pumps and Solar PV technologies in Scottish domestic properties

Source: Consumer Scotland analysis of MCS data dashboard. MCS Certified | Giving you confidence in home-grown energy

Underdeveloped charging infrastructure limits accessibility of electric vehicles to many consumers

As well as decarbonising their homes, there is an onus on drivers to replace, over time, their petrol or diesel fuelled cars with Electric Vehicles (EVs). The new UK Government has committed to bringing forward the ban on sale of new internal combustion engine (i.e. petrol and diesel) cars from 2035 to 2030.[33] Scottish Government policy commits to reducing transport carbon emissions by 56% by 2030 and decarbonising completely by 2045,[34] the same year in which it is estimated petrol and diesel cars will be almost removed from Scottish roads through natural turnover.

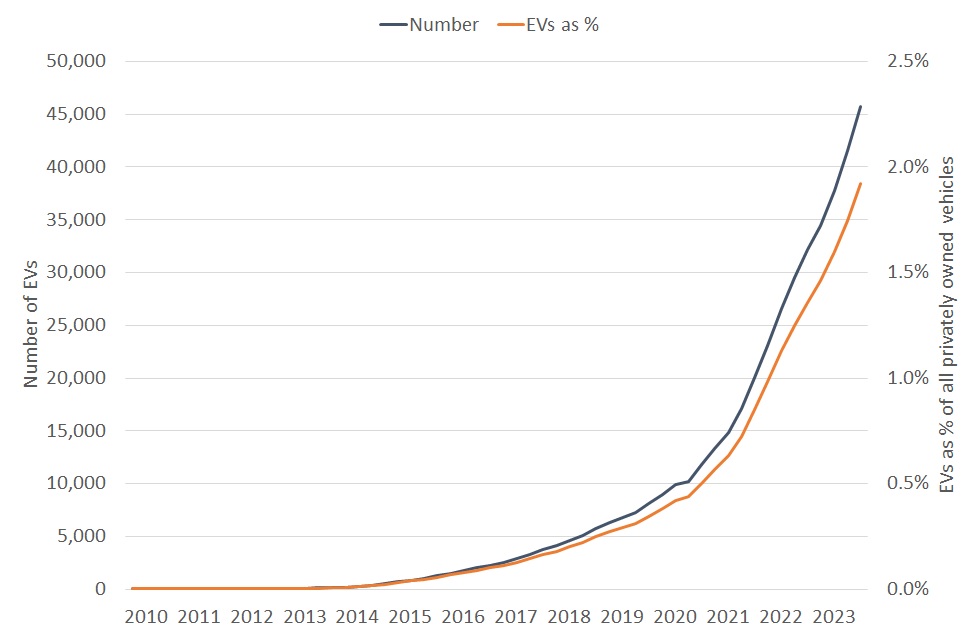

Despite strong growth in EVs over the last few years (Chart 10), numbers of privately owned EVs remain limited. Of the around 2.4m private cars in Scotland at the end of March 2024, only 34,254 were fully electric.[35]

EVs tend to be associated with higher upfront purchasing costs than conventional cars, but can be significantly cheaper to run, particularly where they can be charged whilst parked at people’s homes.

Recent Consumer Scotland research shows that the majority (three-quarters) of current EV owners in Scotland live in circumstances which allow them to charge their vehicles at home.[36] Having access to off-street parking allows EV users to charge their vehicles conveniently and at relatively low cost, especially when used in conjunction with energy tariffs that offer lower charges at off-peak periods, allowing EV users to charge their vehicles cheaply overnight.

Conversely, the costs of public network charging fees are at best comparable to, and can be more expensive than, fuelling petrol or diesel vehicles. There are also concerns around availability and reliability of the public charging network, with significant anxiety about being able to charge EVs when required. As a result, whilst current users of EVs are generally very positive about the EV driving experience, they often do not see EVs as being suitable for every journey. Some express scepticism about an EV-only future, highlighting the need for improvements in EV infrastructure.

One EV driver who participated in the research said:

“Charging is the big negative. We've had a full electric car for 5.5 years and it is still very difficult and inconvenient to take it on long journeys. We thought the amount of chargers and reliability would have improved much more in this time.”

Another said:

“If I had to rely on public charging I’d sell the car and get something else. Public charging is out of control for cost. It takes too long and is very inconvenient.”

Most importantly, limitations of the public charging network risk excluding those who do not have access to private charging from the benefits of EV ownership. Around half of all households in Scotland live in circumstances where charging at home is not likely to be an option, seriously curtailing the uptake and use of EVs, and creating inequalities in the use of this technology.

Improving the public charging infrastructure is critical to maintaining momentum in the adoption of EVs, and in ensuring equality of access to net zero transport.

Chart 10: The number of privately owned electric cars is growing rapidly from a small base

Number of privately owned electric cars registered in Scotland, number and as percentage of all privately owned cars.

Source: Department for Transport, tables VEH0105 and VEH0142. Vehicle licensing statistics data tables - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

All consumers must be able to participate in the transition to net zero

The previous section discussed how car-owners without private parking face substantially higher monetary costs and hassle in charging electric vehicles than those with private parking.

This is one example of the risk that some groups of consumers may be consistently less able to participate in the transition to net zero, undermining the likelihood of the policy aspiration being achieved and creating inequalities in access to new products and services.

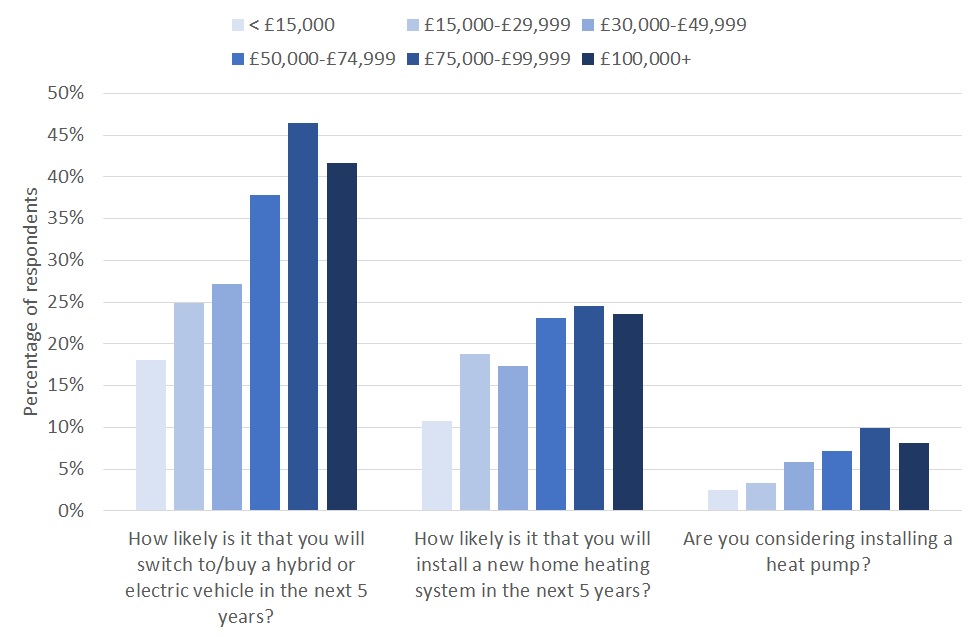

There are a range of reasons why some consumers might be excluded from particular technologies or behaviours, including for example disability, dwelling type, or geographical location. A key factor is financial resources. Consumer Scotland research reveals how consumers’ expectations about the likelihood of adopting net zero technologies are directly related to income.[37] Specifically, higher income households are around twice as likely as lower income households to:

- Think it likely that they will switch to a hybrid or electric vehicle in the next five years

- Install a new home heating system in the next five years

- Be considering installing a heat pump

Of course this doesn’t mean that income is the only factor influencing the adoption of net zero technologies. But it does illustrate the challenges that policy makers need to be cognisant of.

Chart 11: Higher income households are significantly more likely to be considering adopting low carbon technologies

Proportion of respondents in Scotland considering adopting new technologies or installing new heating systems, by household income band

Source: Analysis of Consumer Scotland’s survey of consumer attitudes to the net zero transition, 2023

Conclusions: a rapidly evolving consumer context reiterates the importance of strong consumer advocacy

The world that consumers engage in is evolving rapidly. This evolution can create positive outcomes and new opportunities for consumers where new products, services and markets broaden choice and enhance accessibility.

But it can also create new challenges for consumers where they have to navigate rapidly changing market conditions in established markets, as well as uncertainties and unfairness, particularly in new and emerging markets.

These evolving consumer challenges are driven by a variety of factors. Global economic and political factors have recently underpinned rapid price changes. New and emerging digital technologies create opportunities for consumers but also risks of harm from new pricing and marketing techniques. Broader policy aspirations, notably around the transition to net zero, create new investment requirements and require consumers to engage in new markets.

These challenges are faced to varying extents by all consumers. But some consumers are at greater risk of harm than others. Consumers in vulnerable circumstances are more exposed, financially and emotionally, to the impact of price charges, and are at greater risk of experiencing detriment, partly as a result of less choice and reduced accessibility.

The evolving consumer landscape creates challenges for policy makers too. Policy has to develop proactively in order to create and maintain a framework to support consumers to navigate complex markets, mitigate consumer detriment and unfair outcomes, and ensure they can play an active role in supporting the transition to net zero.

The policy agenda in this respect is broad. It includes:

- Adapting tariff structures – and targeted affordability support – for essential services in order that the substantial investment requirements to sustain those services is shared fairly across consumers.

- Updating regulation and enforcement in relation to new products and services to protect consumers from the risks of new harms as they emerge.

- Ensuring consumers have access to adequate information and advice to engage confidently in markets.

- Supporting consumers to be able to play an active part in the transition to a net zero society, through a mixture of advice and information, financial incentives, and protection against harms.

These are important agendas both for consumers and for the wellbeing of society. Consumer Scotland is pleased to have a key role in these agendas, through our purpose to improve outcomes for current and future consumers.

4. Endnotes

[1] Strictly speaking, under the Act a consumer is an individual or small business who purchases, uses or receives, in Scotland, goods or services which are supplied in the course of a business carried on by the person supplying them. The significance of the italicised text is that consumer to consumer supplies, for example through sales of second-hand items, are not covered by the act.

[2] Consumer price inflation time series - Office for National Statistics

[3] Consumer trends, UK - Office for National Statistics

[4] The household savings ratio measures household savings as percentage of disposable income. Source: ONS Households (S.14): Households' saving ratio (per cent): Current price: £m: SA - Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk)

[5] Source: Ofgem debt and arrears statistics Debt and Arrears Indicators | Ofgem

[6] Consumer Scotland (2024) Insights from latest Energy Affordability Tracker: Causes and impact of energy debt | Consumer Scotland

[7] Scottish Water data, via email

[8]Ofcom (2023) Pricing trends for communications services - Ofcom

[9] Communications Affordability Tracker - Ofcom

[10] IFS (2024) Cheapflation and the rise of inflation inequality | Institute for Fiscal Studies (ifs.org.uk)

[11] Financial Conduct Authority (2022) Financial Lives 2022 survey | FCA

[12] See for example Consumer Scotland (2024) Insights from latest Energy Affordability Tracker: Causes and impact of energy debt | Consumer Scotland

[13] Ofgem’s latest discussion paper on this issue was launched in August 2024 Standing charges: domestic retail options - Ofgem - Citizen Space

[14] Consumer protection study 2022 - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[15] ‘Net monetised cost’ included the initial cost of the product (goods and services), costs incurred by consumers in replacing or fixing a product, and other direct or indirect costs such as loss of earnings and not being able to use another product as a result of the problem

[16] For further discussion, see Consumer detriment in Scotland: what we know | Consumer Scotland

[17] Ofgem Customer Service data shows that the proportion of customers who reported finding it difficult to contact their supplier increased to a record high during the cost-of-living period Customer service data | Ofgem

[18] Consumer Scotland (2024) Consumer detriment in Scotland: what we know | Consumer Scotland

[19] UK Customer Satisfaction Index (UKCSI) ⋆ Institute of Customer Service

[20] A 2023 YouGov survey for example finds that 71% of people surveyed were opposed to the use of dynamic pricing in the scale of concert tickets Half of Britons have been priced out of attending live music events in recent years | YouGov

[21] Government response to consultation on 'Smarter Regulation: Improving consumer price transparency and product information for consumers' - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[22] Source: Alma Economics (2023) Estimating the prevalence and impact of online drip pricing (publishing.service.gov.uk)

[23] National information campaign required to reduce risks to consumers as UK landlines go digital | Consumer Scotland

[24] Statement: Prohibiting inflation-linked price rises - Ofcom

[25] Consumer Scotland (2024) Using Legal Services in Scotland

[26] Consumer Scotland briefing on the Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill.

[27] Net Zero - The UK's contribution to stopping global warming - Climate Change Committee (theccc.org.uk)

[28] The Scottish Household Survey (2022) for example found that 74% of Scottish adults viewed climate change as an immediate and urgent problem. Scottish Household Survey 2022: Key Findings - gov.scot (www.gov.scot). Consumer Scotland research in 2023 found that 75% of consumers are concerned about climate change.

[29] See Consumer Scotland briefing on the Bill Briefing on the Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill - Stage 1 Debate | Consumer Scotland

[30] Many homes in Scotland face barriers to ‘retrofitting’ as a result of their age, construction or ownership (such as tenement flats). For some of these properties, heat networks - large systems of insulated pipes which connect multiple buildings (or multiple units within the same building) to one or more centralised heat sources – may help provide the answer to the question of how to decarbonise such properties. But they bring their own risks for consumers, not least by the creation of a monopoly energy supplier in any heat network zone.

[31] CMA consumer protection in green heating and insulation sector

[32] This issue is the subject of a current Consumer Scotland investigation. Converting Scotland's home heating | Consumer Scotland

[33] Labour manifesto 2024: 12 key policies analysed - BBC News

[34] Mission Zero for transport | Transport Scotland

[35] Vehicle licensing statistics: January to March 2024 - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[36] Consumer Scotland (2024) Consumer Experience of Electric Vehicles in Scotland | Consumer Scotland

[37] Consumer Scotland (2023) Consumers and the transition to net zero | Consumer Scotland