1. Executive Summary

Consumer Scotland is the statutory advocate for heat network consumers in Scotland. In this role, we work to ensure heat networks deliver fair, transparent and reliable services for consumers in Scotland.

Heat networks distribute heat from a central source to multiple properties. They are positioned as a vital technology in Scotland and the UK’s shift to low carbon heating. In fact, the Scottish Government’s Heat in Buildings Strategy identifies heat networks as a ‘near term’ priority. However, without robust regulation, they can present distinct challenges for consumers.

We conducted a review of recent evidence, mostly from grey literature, to identify the key issues facing consumers who are on heat networks in Scotland. These issues will need to be addressed for heat networks to become a fair and affordable solution for decarbonising heating in Scotland’s towns and cities. Before 27 January, 2026, the heat networks market has not had sufficient protections in place to protect consumers. Although the evidence in this area is limited, it indicates that there could be substantial and widespread levels of consumer harm.

This report arrives at a critical moment, just before new regulations take effect. By examining consumer issues now, we can identify key areas that will need close monitoring as regulation embeds and gaps that may require additional policy and advocacy interventions. We also identify priority topics for future research as this market continues to grow with the potential to connect many more consumers over the coming years.

Heat networks in Scotland and Great Britain

The Scottish Government estimates that there are 1090 heat networks that provide approximately 1.35 terawatt-hours (TWh) of heating in Scotland, which is just under 2% of all non-electrical heat consumption (Scottish Government, 2024a). They provide heating and hot water to 30,000 homes, about 1.1% of all Scottish homes (Scottish Government, 2024b), and 3,000 non-domestic properties.

The Scottish and UK Governments consider heat networks a major part of the transition to net zero because they can be built with or switched to low carbon heating sources. However, many heat networks across Great Britain currently rely on gas as their primary heating source (67%) (DESNZ, 2023a).

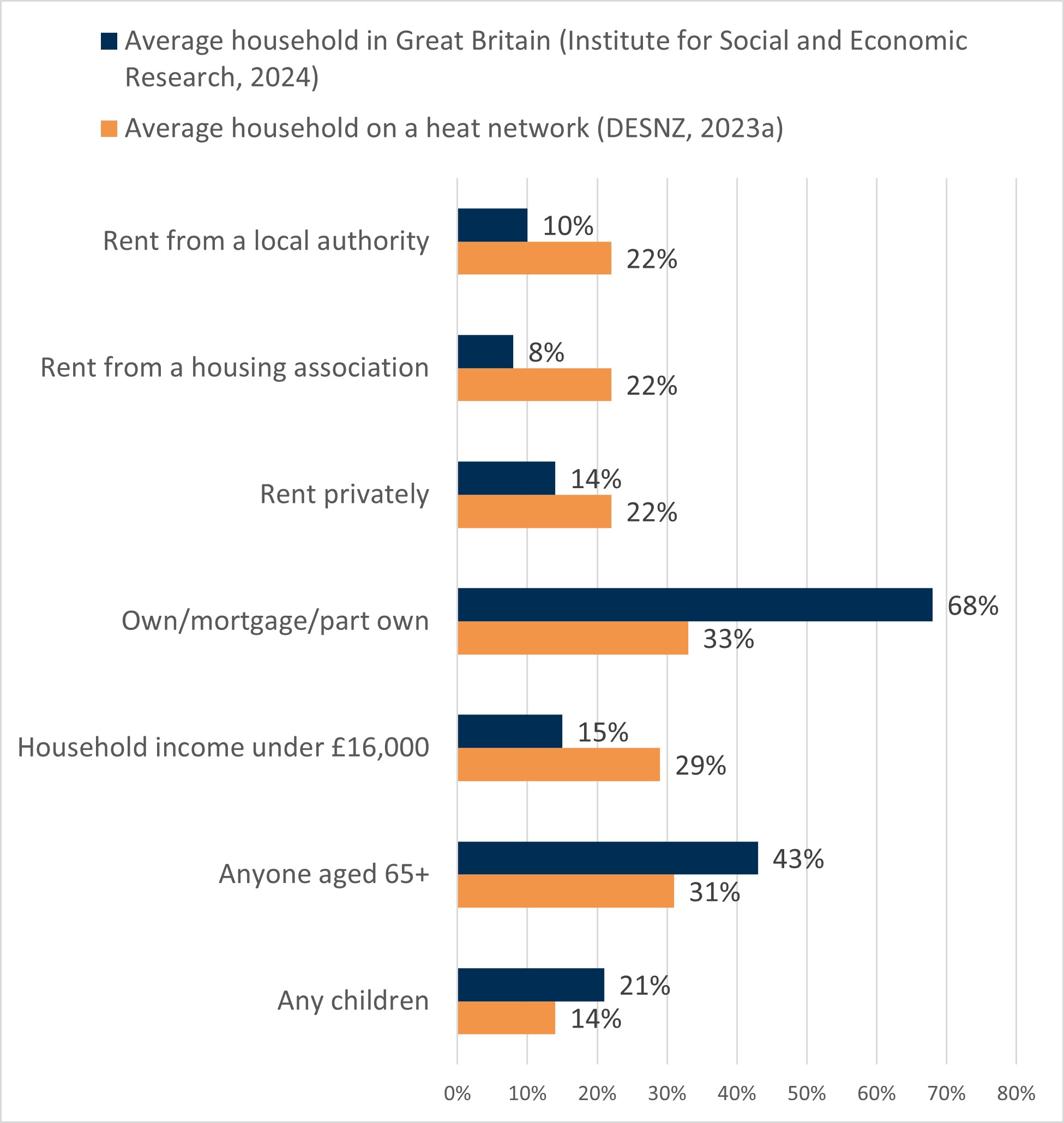

Households on heat networks are more likely to rent and more likely to earn less than £16,000 than the average household in Great Britain (see Figure 3).

In general, people have low awareness and understanding of heat networks. In Scotland, heat networks are one of the least well-known low carbon heating options. Additionally, consumers whose homes are connected to heat networks may not be aware of that or understand how the heat network works.

Heat networks operate as natural monopolies and consumers have limited choice in who provides their heating and hot water. They are often privately owned (65%) and operate on a for-profit basis (56%) (DESNZ, 2023a).

The current regulations for heat networks are limited and there are major gaps in consumer protection. From 27 January 2026, additional regulations will start to come into effect for heat network operators and suppliers, which introduce additional rules to protect customers. We expect that consumers will start to see some improvements after Ofgem begins enforcement. However, we do not expect all issues will be resolved immediately and regulation in this area will evolve over time. Additionally, the heat network market itself is complex and evolving. Monitoring these areas will be key to ensuring that they are effectively forced and to advocating for additional changes to regulation, where needed.

In April 2025, in preparation for forthcoming regulation, Consumer Scotland (in Scotland) and Citizens Advice (in England and Wales) were appointed as consumer advocacy and advice bodies for heat networks. The Energy Ombudsman was also appointed as the dispute resolution service for heat networks across Great Britain.

Key consumer challenges

The limited body of evidence indicates potential consumer detriment in the following areas:

High, varied and volatile pricing

-

- Qualitative evidence indicates that consumers have experienced significant and dramatic price increases in the last few years. High bills can be a significant source of consumer harm with negative impacts on consumer finances, physical health and mental health. Heat network consumers who experienced recent price shocks said that it was a significant source of stress, anxiety, depression, and feelings of helplessness.

- There has been no market-wide research into this area since 2022. Therefore, it is difficult to understand the full extent of this issue.

Metering and billing issues

-

- Qualitative evidence indicates that consumers have reported receiving large and unexpected retrospective bills from their suppliers. Sometimes, these bills put consumers in unforeseen debt which causes significant financial and emotional strain.

- Standing charges on heat networks are generally higher than for gas and electricity, and qualitative evidence indicates that standing charges specifically have increased significantly over the last few years. Additionally, some consumers do not understand how their standing charges have been calculated.

- Survey and qualitative evidence show that there are widespread issues with the billing information consumers receive. This includes receiving no bill at all, receiving limited information on bills (especially for consumers who do not have their own meter) and difficulty understanding bills.

- There is evidence of potentially concerning use of prepayment meters in the heat network market. Some operators may be installing prepayment meters as a default option. Additionally, high standing charges may increase the risk of self-rationing and self-disconnection because it is more difficult for consumers to control costs. Currently, 12% of heat network consumers pay with a prepayment meter (DESNZ, 2023b).

- Some heat networks employ third party companies to deliver services such as billing and customer service. Evidence from 2018 and 2015 suggests that third-party companies can provide poorer billing services, including incorrect information provided to tenants, poor communication or not always collecting payments which cause issues for consumers.

Issues with debt and debt collection

-

- Debt collection options used by heat networks include repayment plans, disconnection and eviction.

- Consumers have reported issues negotiating affordable repayment plans for their debt in recent qualitative research.

- Consumers also reported threats of or actual disconnection in the sector, including as a result of large, unexpected charges without any repayment options or debt from retrospective bills which are harder (or impossible) to anticipate or budget for.

- 32% of heat network consumers pay their heating and hot water bill as part of other charges such as rent (19%) or service charges (13%), also called a ‘bundled’ charge (DESNZ, 2023c). Qualitative evidence shows that some consumers who pay bundled charges with rent have faced eviction due to heat and hot water debt. This is especially concerning as heat network consumers are more likely than the average British household to be social renters and have incomes below £16,000.

Unreliable heating and hot water and poor quality of service

-

- Heat network consumers are more likely to have issues controlling the temperature of their homes than other consumers and in 2017 it was reported that there is persistent overheating in the heat network sector.

- Heat network consumers are more likely to have heating and hot water outages than other consumers and 40% of heat network operators reported unplanned outages in 2022 (DESNZ, 2023b). Sometimes, the cost of repairing systems is passed directly onto consumers.

Poor consumer experience of complaints and redress

-

- Heat network consumers have a higher complaints rate than other consumers—25% of heat network consumers (DESNZ, 2023a) versus 6% for all energy consumers (Ofgem, 2025a).

- There is also a lower satisfaction rate for complaint resolution—9% for heat network consumers versus 48% for non-heat network consumers (DESNZ 2023a).

- Common reasons for dissatisfaction include not knowing who to contact, especially if third party companies are involved, and facing delays in complaint resolution.

Lack of information before consumers buy or let properties on heat networks

-

- Qualitative research also found that consumers receive little information about a property being on a heat network from key stakeholders and intermediaries such as estate agents, property owners, developers and letting agents.

- When information is provided, consumer engagement is limited. This is partly because many consumers do not realise that a heat network is different from more commonly used heating systems, e.g. mains gas. As a result, they are more likely to pay attention to this information only after they have moved into a property.

Areas for further research

There is limited existing evidence of the experience of heat network consumers in Scotland. The current evidence base is either somewhat dated or not representative of the market as a whole. The heat networks sector is an expanding market with a new and developing regulatory framework. As such, it is critical to understand consumers’ experiences and how they evolve.

We have identified a number of priority areas for ongoing monitoring and further research. These are summarised after the relevant key consumer challenges, and they have been compiled in a single list that can be found in Appendix A.

Key areas include:

-

- The impact of the wholesale gas crisis on prices for heat network consumers

- Any unique affordability challenges faced by heat network consumers

- The impact of operational practices on consumers such as prepayment meters, the use of third party companies to manage consumer-facing services and retrospective tariff increases

- The prevalence and impact of debt in the heat network sector, including evictions

In the short term, Consumer Scotland is taking forward research with heat network operators, suppliers and consumers to address some of these gaps. Our research with heat network operators and suppliers aims to get a deeper understanding of how different heat networks in Scotland measure and charge for heat, what methods they use and how these differ, including how heating costs may be bundled with rent or service charges.

We have also commissioned quantitative survey research with heat network consumers to identify the scale and nature of harm currently being caused. The goals of this research are to collect recent and robust evidence to advocate for consumers and have a baseline to assess how well new regulation is working in the coming years.

We will be using this collective evidence base to ensure that once regulation of this sector comes into force, consumer harms are being effectively addressed.

2. Background

Introduction

Heat networks provide centralised heating to multiple properties or buildings. They have the potential to provide efficient, affordable and environmentally sustainable heating (Djinlev and Pearce, 2025). For these reasons, heat networks have emerged as a crucial technology in Scotland’s Heat in Buildings Strategy to decarbonise heat. This market is likely to grow to meet the Scottish and UK Government’s legally binding net zero targets. See the next section on ‘Heat network policy and legislation’ for more information.

Whilst gas and electricity providers have long been subject to regulation, heat networks have, before 27 January, 2026, remained largely unregulated in Great Britain.

In April 2025, Consumer Scotland became the statutory advocate for heat network consumers in Scotland, alongside Citizens Advice in England and Wales. In January 2026, Ofgem will become the regulator for heat networks in England, Wales and Scotland. These are both important steps in ensuring that heat network consumers have sufficient protection and redress in Great Britain.

In this paper, Consumer Scotland has reviewed recent evidence on heat networks and the experience of their users in Scotland. The majority of the evidence used in this paper is from grey literature, meaning research published by non-academic organisations such as UK Government and third sector organisations.

This report starts with an overview of how heat networks work and their key characteristics. It then explains current policies and regulations related to heat networks in Scotland, highlighting that this is a complex area due to the mix of devolved and reserved matters. The report then considers in detail the key challenges heat network consumers in Scotland and the rest of Great Britain are currently experiencing and identifies any key gaps in knowledge.

Overall, Consumer Scotland found that the current evidence base on heat networks is limited. However, existing research indicates that there are consumer protection concerns relating to affordability, metering and billing, debt, quality of service and complaints, when consumers are considering renting and buying properties on heat networks and in and the heat network development process. These issues can cause significant consumer detriment to those affected.

What is a heat network?

Heat networks generate heat at a central location, such as a boiler, combined heat and power plant, waste heat recovery system, heat pump, or other systems (DESNZ, 2022). This thermal energy, in the form of hot water, is then transported through underground pipes to residential, commercial, and public buildings. Within each building, a heat exchanger transfers the thermal energy to provide space heating and hot water to individual properties.

District heating and communal heating are two of the most common types of heat network. Communal heat networks “supply customers within a single building, for example a block of flats” (Ofgem, no date, para. 3) and are currently the most common form of heat networks in the UK (DESNZ, 2023a). District heat networks “supply more than one building, for example housing developments, businesses, offices and shops” (Ofgem, no date, para. 3). They typically involve an extensive network of underground distribution pipes and can integrate various heat sources, including renewable energy and surplus heat from industrial processes (Johansen, 2021).

Figure 1: Diagram of communal and district heat networks

Research by the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) (2023a) found that two out of every three heat networks in the Great Britain (67%) use gas as their main fuel source. Others use combined heat and power gas (7%), electricity (6%), and biomass (6%) as their main fuel sources.

Buildings supplied by heat networks

Currently, Scotland’s heat network landscape comprises an estimated 1,090 operational systems that collectively provide around 1.35TWh of heat annually (Scottish Government, 2024a). These networks service approximately 30,000 residential homes along with 3,000 non-domestic locations, such as commercial and public buildings (Scottish Government, 2024a). This means that heat networks currently supply about 1.1% of Scotland’s 2.7 million homes (Scottish Government, 2024b).

Figure 2: Heat networks supply 1.1% of Scotland’s homes

Heat networks supply 30,000 residential properties out of Scotland’s 2.7 million homes. Each house icon indicates approximately 27,000 homes.

However, these estimates are unlikely to be a comprehensive reflection of the heat network landscape and instead are only indicative. This is because the database used to track heat networks—the Heat Network Metering and Billing Regulations database—is incomplete and non-representative (Scottish Government, 2024a).

How heat networks are structured

Heat networks are often considered natural monopolies, meaning consumers do not have a choice in who provides their heating and hot water (CMA, 2018a). They are often locked into long term contracts with no alternatives. This creates a dynamic in which consumers are heavily reliant on the heat network operator and supplier for pricing and service quality.

Heat networks are monopolies because of the substantial capital investment required for infrastructure development and the impracticality of duplicating networks within the same geographic area (CMA, 2018a; Djørup et al. 2021). As the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA, 2018a) observed, the significant fixed costs of laying insulated pipelines and constructing heat generation plants mean that it is inefficient to establish competing networks within the same area. Additionally, homes need specific technology to connect to a heat network, so consumers cannot easily switch to a property-level system like a gas boiler or a heat pump.

There are a variety of different ownership and cost models for heat networks in Great Britain. There is little evidence specific to Scotland in this area, so this section draws on Great Britain-wide evidence from the most recent UK Government survey (DESNZ, 2023a).

Type of ownership

-

- The majority (65%) of heat network operator respondents across Great Britain reported that their heat network was privately owned.

- 26% said it was publicly owned, and the remaining 9% said it was a public-private joint venture, charity/non-profit, or other.

Cost model

-

- More than half of all heat network operators in Great Britain reported being a for-profit organisation (56%).

- Even though most heat networks intend to make a profit, not many reported doing so. Only a quarter of for-profit heat network operators reported that they actually generated a profit.

- 30% reported a loss.

Who owns versus operates the heat network

-

- Only half of all heat networks in Great Britain are run day-to-day by the same organisation that owns them (47%).

- There are a number of different ways that third party companies are involved in managing heat networks. These include companies that manage metering and billing, companies that provide customer service support, energy service companies and facility management companies. Some third party companies provide several of these services.

- We discuss third party companies in further detail in the ‘Key consumer challenges’ section.

Number of heat networks operated

-

- The majority (57%) of operators who responded to the UK Government survey reported that they operated multiple heat networks.

- Most operators (72%) who have multiple heat networks operate less than 10.

Building type

-

- 30% provide heating and hot water only to residential buildings.

- 34% serve only non-residential buildings.

- 34% serve a mixture of both.

In a recent consultation on consumer protections, DESNZ and Ofgem (2024) defined two different types of organisations that are subject to heat network regulations. The two types are:

-

- Heat network operator: An organisation that is responsible for the day-to-day operation and maintenance of a heat network and its infrastructure.

- Heat network supplier: An organisation that is responsible for the supply of heating, cooling or hot water through a heat network often via contractual terms to end consumers.

There are a number of cases where the operator and supplier are the same organisation.

Previously, UK Government and other bodies have used the term ‘operator’ to apply to both types of organisations. For example, in survey research commissioned by DESNZ. Other research, such as from Citizens Advice in 2025, uses the term supplier as it was recently defined by Ofgem. Throughout this report, we use the term that reflects the original research. This means that mentions of ‘operators’ from the DESNZ 2023 research will often be referring to what are now defined as suppliers, as it is usually referencing the party responsible for working with end consumers to provide them heat and hot water.

Demographics of heat network consumers

There is limited representative evidence to understand the demographics of heat network consumers in Great Britain. One key piece of research in this area is a survey conducted by DESNZ with heat network consumers and operators, see the note below for more information.

Consumer Scotland compared DESNZ heat network consumer survey data (2023a) to survey data about the average household in Great Britain from the Understanding Society UK Household Longitudinal Study (Institute for Social and Economic Research, 2024). We found that households on heat networks who participated in the DESNZ survey are significantly more likely to rent their home rather than own it. They are also almost twice as likely to have a household income under £16,000 a year.

Note on the DESNZ “2022 Heat Network Consumer and Operator Survey” (2023a)

In 2022, DESNZ commissioned Kantar Public to conduct a survey of heat network consumers and operators in Great Britain. This survey is the most comprehensive and up to date indication of broad issues across the heat network market. We make reference to this survey throughout this report.

The survey was completed by 2,244 heat network consumers either online or via a postal questionnaire. The sample included just under 400 consumers in Scotland. A comparative group of 1,733 non-heat network consumers also completed the survey. The questionnaire used was an updated version of a survey undertaken in 2018. The comprehensive approach to sampling, the sample size and the fact it builds on a previous version of the survey are important strengths of this research.

There are also limitations. The survey was conducted in 2022 before many heat network consumers felt the effects of the wholesale gas crisis, so it will not accurately reflect current consumer issues related to pricing, costs, and other related factors such as billing, debt and more. Throughout this paper, we refer to this as the 2022 DESNZ survey to underscore this important context, despite it being published in 2023. The response rate was also lower than intended. Kantar Public noted that this may impact how representative the sample is and how robust the survey estimates are.

Heat network operators were also surveyed as part of this research using Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) and the sample consists of 130 heat network operators across the UK.

As noted earlier, DESNZ uses the term ‘operator’ to refer to both operators and suppliers, as defined by DESNZ and Ofgem (2024).

Consumer Scotland compared DESNZ heat network consumer survey data (2023a) to survey data about the average household in Great Britain from the Understanding Society UK Household Longitudinal Study (Institute for Social and Economic Research, 2024). We found that households on heat networks who participated in the DESNZ survey are significantly more likely to rent their home rather than own it. They are also almost twice as likely to have a household income under £16,000 a year.

Figure 3: Heat network consumers are more likely to rent and have a household income below £16,000

Graph comparing household demographic data for heat network and non-heat network consumers surveyed by DESNZ, 2023a.

Consumer awareness and perceptions

There is low public awareness about low carbon heating systems in the UK, such as heat networks, and why they are important for reducing carbon emissions (ClimateXChange, 2020; Becker et al., 2023; NESO, 2025; Scottish Government, 2025; Smith, Demski, and Pidgeon, 2025). Caiger-Smith and Anaam (2020) and the Scottish Government (2025) have both assessed public awareness and attitudes towards low carbon heating technologies in Scotland. They found that out of all low carbon heating options, heat networks were one of the least well-known. In both surveys, less than one in four Scotland-based respondents were familiar with heat networks (20% from Caiger-Smith and Anaam, 2020 and 24% from Scottish Government, 2025). Other UK-wide studies also found low levels of awareness (Becker et al., 2023; NESO, 2025; Smith, Demski, and Pidgeon, 2025). Respondents to these surveys generally wanted to decrease their carbon footprint but were often unaware of how their heating system contributes to it. They were even less aware of low carbon options, including heat networks.

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA, 2018a) found that many heat network consumers did not fully understand how their heating system worked when they purchased or rented their property. These consumers felt as though the heating system was poorly explained during property viewings, with some unaware that they were even on a heat network. Understanding that the property is connected to a heat network was found to be particularly low amongst private renters, even after moving in (Kantar Public, 2018).

A recent UK survey provided participants with 13 hypothetical heating system profiles, including a district heat network, to understand their attitudes towards them (NESO, 2025). Participants were given details about installation, average costs, and environmental impact. Across all demographics (age, income, tenure, and UK region), district heat networks were consistently ranked in the top three heating system preferences. This suggests that with more information, consumers are open to considering a heat network for the supply of their heating and hot water. However, the survey also found that some consumers, particularly homeowners, are wary of technology that they believe will decrease their control over their bills and comfort. Heat networks were one of these technologies.

Conclusion

In Scotland, heat networks currently supply heating and hot water to only 30,000 homes and 3,000 non-domestic properties. Despite being a relatively small market, the Scottish Government has indicated that heat networks are expected to grow and play an important role in decarbonising Scotland’s buildings and reducing fuel poverty in Scotland’s towns and cities. The Heat in Buildings Strategy 2021 identifies heat networks as an important near-term goal for decarbonising home heating systems.

Heat networks are structured and operated in a wide variety of ways and, before January 27, 2026, there has been almost no regulation about how they should be operated. Consumers who are on heat networks are more likely to rent rather than own their property and are almost twice as likely to have a household income under £16,000. Households on low incomes are less financially resilient in the face of several of the key consumer issues we explore in later sections, including high prices and debt. There is low awareness about heat networks, even among consumers who are on them. In previous research, people who were presented with hypothetical heating system options often ranked heat networks quite highly, which is promising for the Scottish and UK Government’s decarbonisation goals.

In the next section, we explain the key Scottish and UK Government policy and legislation for heat networks.

3. Heat network policy and legislation

Introduction

In the last five years, the UK Government has been developing more comprehensive policy and legislation to regulate the heat network market to a similar level, where possible, as gas and electricity markets. Some responsibilities are reserved with the UK Government, such as the ability to authorise heat networks to operate, consumer protection regulations, and developing technical standards. Other responsibilities are devolved to the Scottish Government, such as the ability to provide permits and licenses for heat networks in specific areas. See Appendix B for a comparison of heat network policy and legislation in Scotland versus England and Wales. Northern Ireland Executive is developing its own heat network policies and regulations for Northern Ireland.

Heat networks will play a key role in reaching the Scottish Government’s and UK Government’s legally binding net zero targets. The Scottish Government’s Heat in Buildings Strategy 2021 (the Strategy) outlines its plan to decarbonise homes and workplaces by 2045. Heat pumps and heat networks are the two home heating technologies that the Scottish Government identified as a ‘near term’ priority in the Strategy. There are a number of properties that will not be suitable for heat pumps, for example, flats without an outdoor space for the heat pump unit. Heat networks or electric panel or storage heaters will often be the only options for consumers in these types of properties. In Scotland, one in three households live in a flat (Scotland’s Census, 2024), compared with one in five households in England and Wales (ONS, 2023). This means that heat networks are likely to play an even larger role in the transition to net zero in Scotland than the rest of Great Britain.

This section outlines the major policies and regulations that are related to heat network consumer protection in Great Britain, including a summary of forthcoming regulations.

Timeline of heat network policy and legislation

2014

-

- The UK Government develops a statutory instrument called the Heat Network (Metering and Billing) Regulations 2014. These are the first regulations for heat networks in Great Britain.

2015

-

- The Heat Trust launches as the voluntary, independent, accreditation scheme for heat networks in Great Britain.

2017

-

- The Competition and Markets Authority launches a market study looking into domestic heat networks, concerned that consumers are not getting a fair deal.

2018

-

- The Competition and Markets Authority recommends that heat networks should be regulated further and that consumer protection is introduced for all heat network consumers so they get the same level of protection as consumers in the gas and electricity sectors.

2020

-

- The UK Government launches the Heat Networks Market Framework consultation on heat network regulation in preparation for more regulation.

2021

-

- The Scottish Parliament passes The Heat Networks (Scotland) Act 2021 which sets targets for heat demand to be met by heat networks. The targets are:

- 2.6 Terawatt hours (TWh) of output by 2027 (3% of current heat supply)

- 6 TWh of output by 2030 (8% of current heat supply)

- The UK Government announces that Ofgem will be the heat network regulator for Great Britain, with Citizens Advice acting as statutory advocate (later changes with creation of Consumer Scotland, see 2023).

- The Scottish Parliament passes The Heat Networks (Scotland) Act 2021 which sets targets for heat demand to be met by heat networks. The targets are:

2022

-

- Consumer Scotland is created, following passage of the Consumer Scotland Act 2020 in the Scottish Parliament.

- The Scottish Government publishes its Heat Networks Delivery Plan.

2023

-

- The Energy Act 2023 passes which introduces the new regulatory framework for heat networks in Great Britain, including the role of Ofgem as regulator.

- Ofgem and the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero’s Heat Networks Regulation – Consumer Protection consultation sets out the role of Citizens Advice and Consumer Scotland as consumer advocacy bodies, and the Energy Ombudsman as provider of the redress and dispute resolution service.

- By 31 December, local authorities in Scotland are required to publish their draft Local Heat and Energy Efficiency Strategies, which should include actions relating to zoning and developing heat networks.

2025

-

- The Heat Network (Market Framework) (Great Britain) Regulations come into force. These regulations apply Part 1 and 2 of the Consumers, Estate Agents and Redress Act 2007 to heat networks. This means that Consumer Scotland and Citizens Advice now act as the consumer advocacy bodies for heat networks. Advice for heat network consumers is available and consumers have the ability to appeal to the Energy Ombudsman.

- The Scottish Government publishes the Draft Buildings (Heating and Energy Performance) and Heat Networks (Scotland) Bill.

2026

-

- In January, Ofgem’s role as regulator goes live. The authorisation regime for heat networks begins. The core consumer protections under the authorisation regime take effect.

2027

-

- In January, the authorisation window for heat networks to register with Ofgem ends.

- Further regulation is expected such as Guaranteed Standards of Performance and the Heat Network Technical Assurance Scheme (HNTAS).

Scottish Government and UK Government heat network policy and regulation

Heat networks are not yet regulated to the same extent as gas and electricity suppliers. This will change from January 2026 onwards when the heat network provisions under the Energy Act 2023 start to come into force. It is a complex area due to the mix of devolved and reserved powers and responsibilities.

Legislative responsibility for consumer protection is reserved to the UK Government, with Ofgem acting as the regulator for the heat network market across Great Britain from January 2026. Ofgem is also developing guidance for industry which will be used in the initial phases of regulation.

This section, therefore, highlights the key elements of the current regulatory framework and the plans from 2026.

Heat Network (Metering and Billing) Regulations 2014

An early example of attempts to introduce standards in the heat networks market was the Heat Network (Metering and Billing) Regulations 2014. This statutory instrument was introduced in 2014 in response to a European Union directive (Directive 2012/27/EU). The key consumer protection requirements are:

-

- Duty to notify: Heat suppliers with a new heat network must notify the Office of Product Safety and Standards and renotify every four years thereafter (Regulation 3).

- Duty to install meters: In some circumstances, heat suppliers must install meters. In general, at least one building-level meter must be supplied for a district network (Regulation 4). Sometimes, a final customer meter is also required, depending on the building class. Final customer meters are usually located in the customer’s individual property. If it is not technically feasible to install a meter for each property, operators should install heat cost allocators (HCAs), thermostatic radiator valves (TRVs) and hot water meters.

- Duty to ensure meters accurately measure: Where meters are provided, heat suppliers must ensure that they accurately record customers’ heating and hot water use and where applicable, suppliers must use heat meter readings to bill customers (Regulation 5).

- Duty to ensure meters and heat cost allocators must continue to operate correctly, be periodically maintained and checked for errors (Regulation 8).

- Duties in relation to billing. The heat supplier must ensure that bills and billing information for the consumption of heating, cooling or hot water by a final customer are accurate, based on actual consumption and comply with mandatory information requirements set out in Schedule 2 of the Regulations. Billing information must be issued by the heat supplier at least twice a year and with every bill issued. At least once a year, a bill based on actual consumption rather than estimated consumption should be issued to the consumer (Regulation 9). However, it should also be noted that a heat supplier does not need to comply with mandatory billing requirements unless it is technically possible and economically justified to do so. The mandatory billing requirements also do not apply where the final customer occupies supported housing, alms house accommodation or purpose-built student accommodation or where the lease began before 27 November 2020 and contains a provision which would prevent billing based on actual consumption.

Heat Networks (Scotland) Act 2021

The Heat Networks (Scotland) Act 2021 establishes a framework for the development and oversight of heat networks in Scotland. Several of the provisions are not yet into force, such as the provisions on licensing, consents and permits. Consumer protection responsibilities are reserved for the UK Government, so it does not include any provisions related to this.

One provision that is in force relates to heat network zones. The Heat Networks (Scotland) Act 2021 requires local authorities to carry out a review to identify whether one or more areas are likely to be suitable for the construction and operation of a heat network (Section 47). If suitable, both local authorities and Scottish Minsters are given the power to designate an area as a ‘heat network zone’ (Section 46).

Following on from this, the Local Heat and Energy Efficiency Strategies (Scotland) Order 2022 stipulated that local authorities in Scotland should include any plans to designate a heat network zone in their Local Heat and Energy Efficiency Strategies. Owners of non-domestic public sector buildings are also required to assess whether their properties are suitable to connect to a heat network (Section 63).

The Act also requires the Scottish Ministers to prepare a plan that sets out how they will increase the use of heat networks in Scotland. It also sets out the statutory targets for Scottish Ministers to meet regarding the supply of thermal energy by heat networks. Heat networks must supply:

-

- 2.6 terawatt hours (TWh) of output by 2027

- 6 TWh by 2030

- 7 TWh by 2035

In 2022, the Scottish Government estimated that heat networks supplied 1.35 TWh of output. The Scottish Futures Trust noted in 2024 that “based on the current rate of deployment and outlook on project pipeline, it is unlikely that statutory targets will be achieved without further intervention.”

Scottish Government Heat in Buildings Strategy

The Scottish Government’s Heat in Buildings Strategy (2021) set out a pathway to achieve net zero emissions from Scotland’s homes and buildings by 2045, with interim targets of a 75% reduction by 2030 and 90% by 2040. It emphasises a just transition, ensuring that efforts to decarbonise heating systems also tackle fuel poverty and protect households in vulnerable circumstances. Key elements of the Strategy include a ‘fabric-first’ approach to reduce energy demand, regulatory requirements for energy performance, and large-scale deployment of heat pumps and other low carbon technologies. Heat networks are a central component of the Strategy, offering an efficient, scalable solution for delivering low carbon heat to multiple buildings and communities, particularly in urban areas.

The Scottish Government have published the ‘Draft Buildings (Heating and Energy Performance) and Heat Networks (Scotland) Bill’ in November 2025 that follows on from the Strategy. The draft bill covers areas such as consenting and permits for new heat networks and regulations for new heat network zones. More specifically, the draft bill is intended to:

“provide for the further regulation of heat network zones, and for a new licensing regime for granting certain rights and powers over land in connection with the installation and maintenance of heat networks; and for connected purposes.” (Draft Buildings (Heating and Energy Performance) and Heat Networks (Scotland) Bill, 2025)

They have set out their intent to introduce it as early as possible in the next Parliament in 2026.

Scottish Government Heat Networks Delivery Plan

The Heat Networks Delivery Plan was published in 2022 and sets out Scotland’s approach to expanding heat networks as a central part of its net zero strategy. It builds on the Heat Networks (Scotland) Act 2021 and the Heat in Buildings Strategy by introducing statutory targets, funding, and regulatory measures to accelerate deployment. The plan aims to deliver clean and affordable heat and reduce emissions, whilst aligning with fuel poverty and economic goals. It will achieve this by:

-

- Establishing statutory targets for heat network deployment to drive progress toward net zero

- Introducing a regulatory framework for licensing and permits/consents

- Committing £300 million through the Heat Network Fund and creation of the Heat Network Support Unit

- Requiring Local Heat and Energy Efficiency Strategies and designated heat network zones

- Promoting skills development, supply chain growth, and use of waste and surplus heat sources

Energy Act 2023

The Energy Act 2023 was a significant milestone for the heat networks sector in Great Britain. The Act appoints Ofgem as the regulator for heat networks in England, Wales and Scotland starting in 2026. It also gives the Secretary of State power to appoint Ofgem as the licensing authority under the Heat Networks (Scotland) Act 2021.

The Act also gives the Secretary of State and Ofgem powers to make secondary legislation to regulate heat networks in Great Britain, which includes consumer protection measures. The Act will achieve this via a variety of different mechanisms, including statutory instruments that delegate legislative powers to DESNZ and Ofgem, Ofgem authorisation conditions and the use of technical standards.

Among other things, the Act states that prices that heat network operators charge consumers and sets out conditions for this to happen to ensure that pricing is fair and “not disproportionate,” however this term remains undefined.

The main provisions relating to advocacy, advice and redress, consumer protection and technical standards are set out below.

Heat Network (Market Framework) (Great Britain) Regulations 2025

The Heat Network (Market Framework) (Great Britain) Regulations 2025 is a statutory instrument that establishes a regulatory regime for heat networks across Great Britain, implementing powers from the Energy Act 2023. The provisions aim to protect consumers and support the growth of heat networks by establishing consumer protections and technical standards in the sector and developing provisions related to fair pricing and impact. These regulations will come into effect from 27 January 2026.

Furthermore, the framework (Part 9) sets out the provision in relation to the licensing authority in Scotland. With responsibility designated to Ofgem, it includes amendments to the Heat Networks (Scotland) Act related to the enforcement of the conditions of a heat networks licence.

The regulations also introduce the first provisions for consumer advocacy, advice and redress in the heat networks sector. The regulations apply Parts 1 and 2 of the Consumers, Estate Agents and Redress (CEAR) Act 2007 to heat networks. This means that as of 1 April 2025, Consumer Scotland (in Scotland) and Citizens Advice (for England and Wales) are appointed as consumer advocacy bodies for heat networks. DESNZ and Ofgem (2025, p.10) explained that Consumer Scotland and Citizens Advice will:

“provide advisory and advocacy services for heat network consumers, ensuring consumer rights are upheld and detriments addressed. Moreover, these bodies work closely with Ofgem and Ombudsman Services, offering insight into issues in the market and input into future heat network policy and regulatory development.”

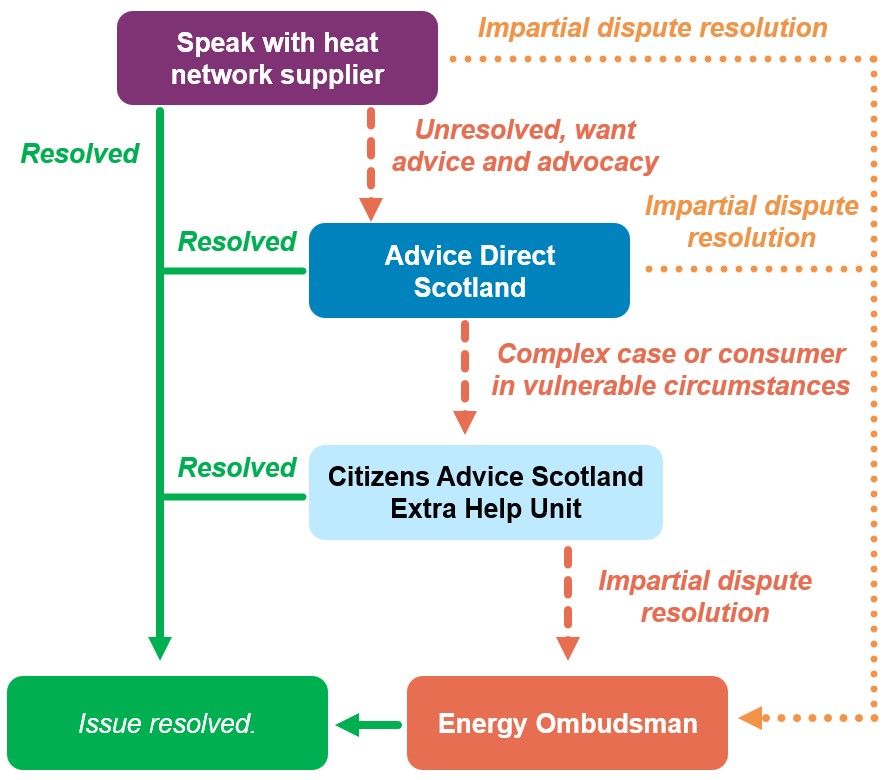

From this date, heat network consumers in Scotland can access free, independent advice and support for heat network-related issues. In the first instance, a customer should direct their complaint to their supplier. If the issue remains unresolved, consumers can access advice from Advice Direct Scotland, via energyadvice.scot. Advisers at Advice Direct Scotland can provide advice and support relating to a range of different issues including billing, affordability and energy efficiency. Advice Direct Scotland can also refer cases to the Extra Help Unit at Citizens Advice Scotland to provide more specialist support for consumers in vulnerable circumstances, where the case is complex or involves the threat of or actual disconnection.

In England and Wales, heat network consumers have access to similar advice support through Citizens Advice. Small businesses also have access to advice.

The regulations also appoint the Energy Ombudsman as the relevant Alternative Dispute Resolution Scheme. When the heat network is operated by a local authority or social landlord, there are instances where the case may instead be taken to the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman in Scotland, the Housing Ombudsman in England or the Welsh Public Services Ombudsman in Wales.

Figure 4: Ideal heat network consumer journey for resolving most issues in Scotland, as of April 2025

Consumers should first contact their heat network supplier. Then, if they would like advice and consumer-focussed advocacy, they should speak with Advice Direct Scotland and, in certain cases, Citizens Advice Scotland Extra Help Unit.

Forthcoming consumer protection

The substantive requirements relating to consumer protection will start coming into force from January 2026, and, at the time of writing, the regulatory rules and guidance are being developed and consulted on. Upcoming regulations will include provisions on customer service, fair pricing, disconnections, vulnerability, complaints, billing and transparency. This approach is similar to how Ofgem regulates the gas and electricity markets.

Technical standards for heat networks

The Energy Act 2023 granted DESNZ powers to design technical standards for heat networks in Great Britain and designated Ofgem to enforce them. DESNZ, the Scottish Government and Ofgem worked with technical experts to create the Heat Network Technical Assurance Scheme (HNTAS), to introduce specific technical standards and ensure compliance with those standards. These standards will address design, construction and operational requirements such as flow temperatures, insulation and performance monitoring. The standards will apply to all heat networks, from small communal systems to city-wide schemes, and will be enforced through impartial assessment and certification. According to DESNZ, HNTAS “has the potential to reduce carbon emissions by making heat networks more efficient, reduce capital and operational costs, and improve consumer experience” (DESNZ, 2025).

They build on voluntary guidance from the CP1 Heat Networks: Code of Practice for the UIK (2020) developed by the Chartered Institute of Building Services Engineers (2021) and will be enforced through impartial assessment and certification by independent appointed bodies. Prior to the Energy Act, regulation was limited to the Heat Network (Metering and Billing) Regulations 2014, which focused on improving energy efficiency and fairness through mandatory metering and consumption-based billing, but did not set comprehensive technical performance requirements.

Heat Network Efficiency Scheme

The CMA’s market study identified that some existing heat networks were operated sub-optimally, leading to poor outcomes for consumers such as higher bills. In response, the UK Government launched the Heat Network Efficiency Scheme (HNES) to help to improve existing networks by enabling optimisation studies to identify the actions needed to improve heat network efficiency and the delivery of intervention and improvement measures. This support is only currently available in England and Wales.

Voluntary consumer protection scheme

The Heat Trust is a voluntary consumer protection scheme which has operated in the heat networks sector since 2015. The scheme sets minimum standards of customer service and consumer protection for heat suppliers in Great Britain (Heat Trust, 2023). Heat suppliers that are registered with the Heat Trust are required to follow a structured complaints process. Through this route, consumers were offered an independent route to dispute resolution through the Energy Ombudsman (Heat Trust, 2023), or, in some instances, the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman. However, Heat Trust membership is not mandatory and heat suppliers voluntarily register with the scheme. There are currently seven heat network sites in Scotland registered with the Heat Trust (Heat Trust, 2025).

International approaches to heat network regulation and consumer protection

The European heat networks market is one of the most mature heat network markets in the world (Data Insights Market, 2025). The market is especially mature in Northern Europe. For example, heat networks provide for 45% of Finland’s and 60% of Denmark’s residential and commercial heating demands (Euroheat & Power, 2024).

European heat network regulations vary significantly across countries (Billerbeck et al., 2023). ClimateXChange (2018) reviewed heat network regulation in seven European countries for the Scottish Government. They highlighted the need to implement a balanced regulatory structure that protects consumers while ensuring long term investment in heat networks.

Relationship between level of regulation and outcomes

Billerbeck et al. (2023) published an analysis of all European heat network regulatory systems. They found that overall, the ways that heat networks are regulated across Europe vary widely. Their research found no clear relationship between type of regulation and the degree of decarbonisation, or the percentage of households connected to a heat network. Instead, these outcomes appear more tied to other policies and national context.

They concluded that there is no clear singular model for heat network regulation and that each country should tailor it to their own context and needs.

Approaches to price regulation—costs and transparency

More than half of all European countries with heat networks have “consistent price rules or rely on price control mechanisms” (Billerbeck et al., 2023, p. 12). In contrast, countries with fewer or less robust regulations, such as Poland, Bulgaria and the UK, often experience transparency issues and monopolistic pricing. These lead to inefficiencies and higher costs for consumers (Schmidt, Kallert and Blesl, 2017).

Odgaard and Djørup (2020) argue that consumers in a privatised heat network market should have the option to switch to different heating systems. However, in both Sweden (Odgaard and Djørup, 2020) and the UK, this is not generally a simple option for consumers. The authors conclude that, in contexts where switching is not an option, a liberalised heat network market must be supported by substantial regulation (Odgaard and Djørup, 2020) to achieve transparent pricing. This requires the regulator to have accurate information from heat networks about what they are charging consumers so that this information can be made publicly available. The process of collecting this information takes time, but they argue that this regulation should be in place before heat networks are allowed to set their prices in a liberalised market. This information is not currently collected in the UK.

Regulation around ownership models and cost models

In Denmark, where many properties are connected to heat networks, all heat network operators and suppliers are required to operate as not-for-profit to address concerns about price exploitation (Frerk and MacLean, 2017).

In Sweden, heat networks were under municipal ownership until the liberalisation of the energy market in 1996, which permitted private companies to operate in the sector (Magnusson, 2016). In the decades following, many publicly owned heat networks were acquired by private companies (Magnusson, 2016). Consequently, prices were no longer based exclusively on delivery costs, leading to higher charges for consumers. In response to public protests and pressure about cost increases, some heat networks were transferred back into public ownership (Odgaard and Djørup, 2020).

Conclusion

Heat network regulation in Great Britain is developing in response to the need for decarbonisation, affordability and consumer protection. While recent legislative measures such as the Heat Networks (Scotland) Act 2021 and the UK’s Energy Act 2023 mark significant progress, continued refinement will be necessary to address ongoing and emerging consumer challenges.

Forthcoming regulation will come into effect in January 2026. Additionally, other legislative and regulatory areas are still developing such as technical standards for existing and new heat networks which will have an impact on issues such as bills and efficiency. In short, heat network regulation and how it impacts consumer experiences are areas that will evolve over time.

4. Key Consumer Challenges

Introduction

This section outlines the some of the known challenges that heat network consumers across Great Britain experience, based on the limited available research published to date. These challenges relate to:

-

- Pricing and affordability

- Metering and billing

- Debt

- Reliability and quality of service

- Complaints and redress

- Information for consumers when moving into a property on a heat network

- Consumer protection in the development process.

In some key areas we have also identified gaps in the existing evidence, including some potential areas for future research to consider.

Pricing

High prices

Until recently, evidence indicated that most heat networks in Great Britain provided comparable or cheaper heating and hot water compared with other systems, including gas boilers (CMA, 2018a; DESNZ, 2023a). In the 2022 survey, heat network consumers had a median annual heating cost of £600, compared to £960 reported by non-heat network consumers (DESNZ, 2023a). Despite this, some heat network consumers believed they were facing disproportionately high costs, with 60% stating that their heating costs were higher than expected (DESNZ, 2023a). Though £600 was the average in 2022, costs also varied significantly. In fact, in the same survey, one in ten reported an average bill of £2,000 or more (DESNZ, 2023a).

This survey was undertaken prior to when many heat network consumers likely experienced price increases. The crisis in wholesale gas markets began to impact gas and electricity consumers in 2021 when unit prices for energy increased significantly and government intervention was required to control prices. Recent qualitative evidence suggests that heat network consumers felt the impact of this later, mostly from 2023 onwards (Citizens Advice, 2025b). This delay is likely because heat networks often have commercial contracts for gas which are fixed over several years. Therefore, operators and suppliers faced price increases when these contracts came up for renewal rather than in direct response to the market. Additionally, heat network consumers are not protected by the same government interventions as other consumers, such as the price cap.

To date, there is no research that is representative of all heat network consumers that explores the impact of the wholesale gas crisis on prices. However, research commissioned by Citizens Advice (2025b) found that, since 2023, the heat network consumers they interviewed have experienced “significant” and “dramatic” increases in their heating and hot water costs. They found that most interviewees’ bills had often doubled or tripled in this time. For example, one Edinburgh consumer’s bills were stable for a seven-year period up until 2024, only increasing £34 annually during that time. Then, in 2024/25, their bill increased by £976 compared to the previous year. This represented a 243% increase.

High heating and hot water bills can cause significant negative impacts for consumers who cannot afford them. There is extensive research available on the negative financial, physical health, and mental health impacts from unaffordable energy bills (Middlemiss, 2022; Bennett and Khavandi, 2024). Heat network consumers interviewed by Citizens Advice (2025b) noted that the financial shocks from unexpected price increases they have experienced since 2023 were a significant source of stress, anxiety, depression, and feelings of helplessness. The sudden and unexpected price increases also led to consumer uncertainty about their ability to cover future heating and hot water costs. High prices had a particular impact on older homeowners who are retired and live on fixed incomes. Some consumers in this situation were worried that they might have to sell their homes in the future if heating and hot water became completely unaffordable.

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA, 2018a) has cautioned against imposing a price cap. It warned that the UK’s heat network market is diverse and complex, and such a measure could become a default pricing benchmark rather than an upper limit, which could increase bills for some consumers.

Note on Citizens Advice (2025b) “System Critical - No margin for error in new heat network rules”

As noted above, recent evidence on heat network consumers is limited. Consequently, this paper draws heavily on the DESNZ survey referenced earlier and on recent qualitative research conducted by Citizens Advice. A summary of the key features of the Citizens Advice research is provided below.

In 2025, Citizens Advice published a qualitative research report delivered by the Social Agency. Researchers conducted interviews with 50 households who are on heat networks across Great Britain, exploring the challenges they face. These households were chosen because they were at heat network sites with known affordability and financial detriment issues. As such, these findings highlight issues that are likely to be particularly problematic in the sector rather than being indicative of practices in the whole sector.

This research is particularly insightful for two reasons. First, it is one of the only research projects on heat network consumer detriment that has been conducted since heat network consumers experienced recent energy price increases from the wholesale gas crisis. Second, as it is qualitative research, it provides an in-depth exploration of some of the key challenges heat network consumers are currently experiencing and the impacts of those challenges.

In terms of limitations, it is important to note that, as with all qualitative research, its findings are not intended to be representative.

This research uses the term ‘supplier’ to refer to the organisation who interacts with consumers, broadly consistent with the 2024 DESNZ and Ofgem definition. Therefore, we also use the term supplier were referencing this evidence.

High heating and hot water bills can cause significant negative impacts for consumers who cannot afford them. There is extensive research available on the negative financial, physical health, and mental health impacts from unaffordable energy bills (Middlemiss, 2022; Bennett and Khavandi, 2024). Heat network consumers interviewed by Citizens Advice (2025b) noted that the financial shocks from unexpected price increases they have experienced since 2023 were a significant source of stress, anxiety, depression, and feelings of helplessness.

The sudden and unexpected price increases also led to consumer uncertainty about their ability to cover future heating and hot water costs. High prices had a particular impact on older homeowners who are retired and live on fixed incomes. Some consumers in this situation were worried that they might have to sell heir homes in the future if heating and hot water became completely unaffordable.

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA, 2018a) has cautioned against imposing a price cap. It warned that the UK’s heat network market is diverse and complex, and such a measure could become a default pricing benchmark rather than an upper limit, which could increase bills for some consumers.

Price regulation case study: Sweden

Sweden’s heat network market is an interesting case study to understand how different regulatory approaches impact prices for consumers. A report for ClimateXChange (2018) details how for several decades, heat networks were owned by public bodies and were heavily regulated. Then, in 1996, the heat network market was ‘liberalised’ and many heat networks were sold to private companies and regulatory oversight loosened. Afterwards, consumers immediately experienced significant bill increases and prices rose by an average of 15%. The public were dissatisfied with rising prices and perceived that private heat network operators and suppliers were taking advantage of their monopoly status. This led to widespread protests and a national debate over regulatory intervention.

These concerns ultimately resulted in the introduction of Sweden’s 2008 District Heating Act, which mandated greater transparency in pricing but stopped short of direct price regulation. Despite the absence of formal price controls, approximately 70% of heat suppliers voluntarily signed up for pricing agreements based on market projections, which stabilised costs. Interestingly, Sweden now has lower average heating costs than some countries with more direct regulatory oversight.

Upcoming Ofgem regulation on pricing

Ofgem’s upcoming heat network regulations include plans to introduce a fair pricing framework. The authorisation conditions place a general obligation on heat networks to provide fair and proportionate prices. By focussing on “disproportionate” pricing, it is intended to reduce high prices on the most expensive heat networks (Ofgem, 2025c). Ofgem have indicated that they do not intend to predefine terms such as “fair” or “disproportionate” (Ofgem, 2025c).

Areas for further research on pricing

It is crucial to monitor the costs consumers are paying for their heating and hot water on heat networks. Improving the data collected on consumer prices will help Consumer Scotland and other advocacy organisations identify consumer protection concerns and trends to inform advocacy work for policy and regulatory change.

Potential areas for further research include:

-

- To what extent, when and how did the wholesale gas crisis impact heat network consumers? What are the lasting impacts of this, and how can this be avoided in future?

- A representative sample of heat network consumers to track prices:

- Over time to understand trends and levels of volatility

- Between types of heat networks (ex: communal vs district, ownership structure, cost model, size, etc.)

Metering and billing

Citizens Advice (2025b) reported that as of May 2025, billing issues made up 64% of their heat network cases.

The processes for metering and billing vary between heat networks. How a consumer pays for their heating depends on whether they have a meter and what billing options are available to them. Heat network operators and suppliers are required to use a meter to measure the amount of heating and hot water delivered to a building, for example a block of flats. However, they are not always required to install ‘final customer meters’ that measure the consumption of heating and hot water for each individual property (Heat Network (Metering and Billing) Regulations, 2014). In this paper, we refer to these as ‘property-level meters.’

The payment methods commonly used by heat networks are:

-

- Bills based on consumption: When a consumer pays for their heating and hot water based on the amount they use, measured by a property-level meter. This can be done through regular bills or by a prepayment method, such as a prepayment meter. 47% of operators calculate residential consumer bills based on consumption (DESNZ, 2023b). It is so far unknown what proportion of consumers use a prepayment method.

- Bills based on building usage, divided by occupant: When a consumer pays an equal share of the total amount of heating and hot water used by all occupants in a building. For example, if there are ten flats in a building, each household pays 10% of the heating and hot water costs during the billing period. This is one approach operators take when the consumer does not have a property-level meter. 13% of operators bill residential consumers this way (DESNZ, 2023b).

- Bills based on estimated consumption: When a consumer pays for the amount of heating and hot water that the operator estimates they have used. This is generally done through regular bills, and often because the consumer does not have a property-level meter. 12% of operators bill residential consumers this way (DESNZ, 2023b).

- Bills based on the size of the property: When a consumer pays for a share of the heating and hot water used by the entire building based on the size of their property, rather than an even share. 2% of operators bill residential consumers this way (DESNZ, 2023b).

- Bundled billing: About one third (32%) of heat network consumers pay their bill with rent (19%) or with a central service charge (13%). This is called “bundling”. Bundled charges can be based on actual consumption, estimated consumption, or a flat fee. This means consumers can face eviction for energy debt, which is covered later in Debt and debt collection.

About half of heat network operators (48%) surveyed in 2022, noted that some or all of their heat networks billed consumers based on the property as a whole, rather than individual tenant/occupant usage (DESNZ, 2023a). Non-metered billing is more common with older heat networks (BEIS, 2018), especially older, local authority-owned heat networks, where heat and hot water charges are bundled with rent (Which?, 2015). DESNZ survey data (2023b) also shows that heat networks operated by local authorities are least likely to bill consumers based on consumption measured by a property-level meter.

Overall satisfaction with heat networks is strongly associated with whether or not consumers perceive that the price they are charged for heat and hot water is fair (DESNZ, 2023a). Research undertaken by Citizens Advice (2025b) found that the non-metered consumers they interviewed did not feel like they understood what they were paying for. Survey evidence also shows that non-metered consumers were worried about paying more than their share to subsidise the bills of others (BEIS, 2018; DESNZ, 2023a). Furthermore, the research conducted by Citizens Advice (2025b) suggests that consumers would generally prefer to have bills based on their individual heat and hot water consumption. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) (2018) highlights that when consumers are billed based on their individual heat consumption, it provides the “highest degree of consumer empowerment and delivers the best results in terms of demand-side energy efficiency”.

European Union (EU) law requires that consumers in member countries “must be provided with competitively priced meters that accurately reflect their heat consumption” (Billerbeck et al., 2023). However, there is evidence to indicate that this may not be fully implemented. The EBRD (2018) conducted research into heat network infrastructure in nine countries in the region. Most EU countries had very high adoption levels of property-level meters. However, not all did. For example, only 32% of surveyed flats on heat networks in Bucharest, Romania had their own meters.

Retrospective tariff increases and back billing

Citizens Advice (2025a, 2025b) found that some interviewees reported receiving unexpected and often significant heat bills for previous time periods. The research findings noted that these bills could total thousands of pounds (2025b), putting the household in debt and causing significant financial and emotional strain.

There tends to be two main types of retrospective bills: retrospective tariff increases and back billing.

Retrospective tariff increases happen when the heat network increases their charges and bills consumers for the difference after the billing period has passed. The two potential justifications for retrospective tariff increases may be:

- The unit price for energy increased for the heat network operator/supplier and,

- There were higher than expected maintenance costs that are passed on to consumers.

Various consumers interviewed noted that they had been threatened with disconnection because of debt from retrospective tariff increases (2025b).

Back billing is when a supplier sends a new bill for previous energy used because the consumer was not billed correctly, or at all. For example, if the heat network supplier set the wrong direct debt amount or if there was an issue with how the meter measured the property’s usage. This is different from when a consumer has not paid a bill or when the supplier cannot take a meter reading due to obstruction from the consumer (Ofgem, 2025b Section 7.2.3). Citizens Advice’s (2025b) qualitative research found that interviewees in non-metered properties are more likely to receive back bills.

High and increasing standing charges

Heat network consumers often pay a higher portion of their bill via standing charges. This is different from a standard gas and electricity bill where the unit rate usually accounts for the larger proportion of the costs. For example, in 2016/17, the average user of a heat network located in London would expect to pay £402.68 in standing charges each year. During the same period, the average gas consumer’s standing charges per year was £86.37 (Johnson, 2022). Similarly, Insite Energy, a heat networks services provider, self-published their average standing charge compared with gas and electricity. Insite charges 69.42p per day, compared with 31.66p for gas and 60.12p for electricity (Insite Energy, 2024).

There are a number of reasons why heat network standing charges may be higher than for gas and electricity (Johnson, 2022), including:

-

- Heat network consumers sometimes pay for the cost of equipment in the home through standing charges. This is opposed to paying upfront, like how consumers often pay for their own gas boiler.

- The cost of the overall system is more than individual heating systems, but with the theoretical benefit of reducing the cost of energy per unit.

- Heat networks are a relatively new form of infrastructure in the UK, meaning that the labour force and supply chain are still developing.

High standing charges can be a source of frustration for heat network consumers because some believe standing charges should be comparable to the gas and electricity market (Johnson, 2022).

The recent Citizens Advice qualitative research report (2025b) found that standing charges have increased for some heat network consumers in recent years. Almost all interviewees reported that their standing charges have increased by 50-100% since 2022. However, standing charge rates do not seem to be consistent across the sector. Overall, interviewees reported very different levels of standing charges between heat networks (Citizens Advice, 2025b).

Another challenge is that some heat network consumers do not understand how their standing charge is determined. Interviewees shared that heat network suppliers were not transparent enough about standing charges, especially when suppliers fail to explain why standing charges have increased (Citizens Advice, 2025b).

Lack of billing information

Consumers on heat networks have reported feeling confused and frustrated by the limited and poor quality information they receive. Under the Heat Network (Metering and Billing) Regulations 2014, operators/suppliers must provide a bill with an explanation of how the bill was calculated at least once a year. However, only 70% of consumers surveyed by DESNZ (2023a) reported receiving a bill at all. This is 14 percentage points lower than non-heat network consumers (84%; DESNZ, 2023b). This number is even lower for social housing tenants on heat networks, of whom only 58% reported receiving a bill (DESNZ, 2023b). The CMA (2018a) have reported many complaints about consumers not receiving regular bills.

Even when consumers do receive a bill, they report having difficulty understanding what they were charged for (CMA, 2018a; DESNZ, 2023a; Citizens Advice, 2025b). Consumers of local authority-owned heat networks reported the least amount of information provided on their bills out of all ownership organisation types (DESNZ, 2023a).

There are two commonly reported issues with heat network billing information. First, there is little to no information about charges. When consumers did receive bills, about half or less showed at least one of the following pieces of information: the amount of heating used (52%), the amount charged for each unit of heat (52%), or a description of how the bill was calculated (49%) (DESNZ, 2023a). Other research has indicated that consumers often find heat network bills unclear and confusing (Which?, 2015). Second, consumers who do not have a property-level meter reported particular issues. Surveyed consumers in non-metered properties were more likely to received “too little” information on their bills (DESNZ, 2023a).

Additionally, research on heat network consumers with prepayment meters reported that when they find it difficult to understand their rates, they also have a hard time budgeting (Citizens Advice, 2019).

Unclear billing was found to be a particular issue for consumers in vulnerable circumstances. The DESNZ survey (2023a) found that consumers in vulnerable circumstances were almost twice as likely to disagree with the statement: “information provided was clear,” compared to households without consumers in vulnerable circumstances (21% vs 12%).

Without clear information, consumers were less likely to think they were paying a fair price or to be satisfied with being on a heat network (DESNZ, 2023a). However, there is evidence to suggest that the amount of information provided on bills is improving. Since 2017, more consumers have received information about the amount of heating and hot water consumed, the cost per unit of energy and the time period covered by a bill and (DESNZ, 2023a).

Prepayment meters

According to the 2022 consumer survey, 12% of heat network consumers pay for their heating and hot water with a prepayment method and one in five heat network operators provide a prepayment option to consumers (DESNZ, 2023b). This is similar to the latest data on gas and electricity consumers, wherein 11% reported in 2021 that they were on prepayment meters (Ofgem, 2021). However, it should be noted that this fieldwork was done before the wholesale gas crisis which may have impacted this figure.

Figure 5: 12% of heat network consumers pay via prepayment method

12% of the consumers surveyed by DESNZ in 2022 (2023b) pay with “pre-payment meter, pre-payment card or pre-payment account (where credit is topped up on a key, card or online account).”

A 2018 UK Government survey (BEIS, 2018) found that prepayment meters were mentioned favourably by many operators (both public and private) for several reasons. First, prepayment meters reduce the financial risk to heat network operators. They reduce the potential for unpaid charges and are an effective tool for recovering debt from consumers. Second, some stakeholders in the heat network industry have stated that they believe some consumers prefer prepayment meters, especially low-income consumers, because they provide “greater visibility and control to residents over their consumption” (BEIS, 2018). Several respondents to a recent UK Government consultation said that not-for-profit heat networks prefer prepayment meters and some “opt to install and use prepayment meters in all new developments” (DESNZ and Ofgem, 2024). Consumer Scotland has noted similar statements in its industry engagement that indicate prepayment meters are being installed by default by some suppliers and operators.

Qualitative research commissioned by Ofgem found that gas and electricity consumers perceived prepayment meters to have some benefits such as better visibility and control over energy use and spending (Savanta, 2023). Consumers reported improved flexibility with when and how they pay and that prepayment meters made household budgeting easier, especially with increasing energy prices.

However, prepayment meters are also linked to consumer detriment. Research specific to heat network consumers on prepayment meters found several issues. Some consumers:

-

- Did not receive appropriate support with outages or issues with topping up (Citizens Advice, 2019)

- Found it difficult to understand their rates such as standing charges (Citizens Advice, 2019)

- Had a lack of places to top-up (Changeworks, 2015)

- Had issues with self-disconnection (Changeworks, 2015; Citizens Advice, 2019). In 2015, Changeworks found that 8 out of the 13 social housing providers with heat networks that they spoke with had experienced tenants self-disconnecting.

Qualitative research with social housing tenants on heat networks conducted ten years ago found that prepayment methods had the highest dissatisfaction rates out of all payment methods (Changeworks, 2015). However, as some consumers preferred it, the authors recommended offering it among a variety of payment options.

Heat networks often have higher standing charges, which may increase the risk of self-disconnection and self-rationing for consumers on prepayment meters (Citizens Advice, 2019; Citizens Advice, 2025b).

More broadly, the widespread use of prepayment meters also raises socioeconomic and health-related challenges. Prepayment meters for energy are linked to economic and health deprivation, exacerbating financial precarity for households in vulnerable circumstances (Ding et al., 2022). Prepayment meters can cause households to ration their heat and hot water to save money, which can worsen certain health conditions and increase emergency respiratory hospital admissions (Ding et al., 2022). There are also reported mental health impacts linked to prepayment meter usage. Consumer Scotland found that 56% of gas and electricity consumers on prepayment meters in 2022 reported that their mental health was affected ‘a lot’ or ‘a fair amount’ by trying to keep up with energy bills (Consumer Scotland, 2023).

Third party billing companies

Some heat network operators use third party companies to manage consumer-facing services, such as billing and customer service (BEIS, 2018). Research from 2017 highlighted that outsourcing companies may sometimes provide poorer billing services, such as incorrect information being provided to tenants, poor communication or failing to collect payments (Changeworks, 2015).