1. Executive Summary

In 2024, Consumer Scotland published a research report titled Consumer Perceptions of and Engagement with the Transition to Net Zero. This research found that while levels of net zero awareness and environmental concern are generally high, many consumers are unsure about how they can personally contribute to meeting net zero targets.[1] This new briefing utilises evidence from that research to better understand consumer attitudes and motivations when making choices about the transport methods they utilise.

Though the majority of consumers (65%) would like to reduce their carbon emissions by using more environmentally sustainable transport methods, many either face significant barriers in doing so, are unsure of how to do so, or are unconvinced that their behaviour changes could have an impact.

For those able to utilise more environmentally sustainable transport options, the most common choices were using public transport instead of a private car, trying active travel, reducing car mileage, and working or volunteering from home. The ability to access such options, however, differ significantly in some cases based on factors such as whether consumers live in rural or urban areas with established public transport and active travel infrastructures, their household income, or whether or not they are disabled.

Transport behaviours are often habitual and ingrained, and the rate at which more sustainable transport habits are being adopted will not be sufficient to meet national targets for modal shift from car use to public transport, or for emissions reductions. This is, in part, due to the barriers to choosing sustainable transport highlighted in our research. Issues around accessibility for disabled people, concerns around the safety of active and public travel, and the time such journeys take are commonly reported, but the primary barriers cited by consumers are around the availability and cost of such transport methods.

As with other markets, making sustainable choices more cost-effective and convenient for consumers is central to a successful and just transition to a lower emission transport market. This of course means that efforts must be made to reduce the cost of public transport, but a wider systemic approach is also needed to improve the experience of using public transport and to achieve net zero goals.

Targeted investment in underlying infrastructures and service provision should be considered to improve the availability and reliability of public transport options. For those consumers with poorer access to public and active travel options, especially those in rural areas, EVs will play a crucial role in decarbonising transport, and so Transport Scotland will need to drive progress in achieving the action set out in its Vison for Scotland’s Public Electric Vehicle Charging Network. Engagement will also be needed with consumers about how their diverse needs can be better met to make public transport a more viable option, while highlighting the personal and environmental benefits of sustainable transport habits could also lay the groundwork for future policy interventions.

2. Who We Are

Consumer Scotland is the statutory body for consumers in Scotland. Established by the Consumer Scotland Act 2020, we are accountable to the Scottish Parliament. Consumer Scotland’s purpose is to improve outcomes for current and future consumers and our strategic objectives are:

- to enhance understanding and awareness of consumer issues by strengthening the evidence base

- to serve the needs and aspirations of current and future consumers by inspiring and influencing the public, private and third sectors

- to enable the active participation of consumers in a fairer economy by improving access to information and support

Consumer Scotland uses data, research and analysis to inform our work on the key issues facing consumers in Scotland. In conjunction with that evidence base we seek a consumer perspective through the application of the consumer principles of access, choice, safety, information, fairness, representation, sustainability and redress.

Our general function is to provide consumer advocacy and advice with a view to achieving more positive consumer outcomes. We also have a role in a promoting sustainable consumption of natural resources, and other environmentally sustainable practices in relation to the acquisition, use and disposal of goods by current, and future, consumers in Scotland.

Consumer Scotland’s Strategic Plan for 2023-2027 sets out three cross-cutting themes which inform our focus and priorities across this period.[2] Understanding and influencing Scotland’s approach to climate change to ensure that this delivers effectively for consumers is one of these key themes.

Our 2024-25 Work Programme commits us to identifying ways to improve the consumer experience for public transport users and to highlighting barriers that they face when trying to access public transport.[3]

3. Introduction

Scotland's climate is changing faster than expected and this will have a wide range of impacts on communities, consumers, and businesses in Scotland. Policies aimed at climate change adaptation and mitigation are therefore an urgent priority across the policy landscape in Scotland.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC) has estimated that around a third of total necessary emissions reduction from now until 2050 will directly involve changes at the household level.[4] In order to achieve this scale of change, significant action will be required from all sectors. Transport is the biggest contributor of greenhouse gas emissions in Scotland, making up over a quarter of all national emissions.[5] Emissions are reducing more slowly in the transport sector than in other sectors. Of those emissions, the majority come from private car use (41%).[6] Detailed analysis prepared by Regional Transport Partnerships, and cited by Audit Scotland, shows that most of the car kilometres driven are longer distance journeys that would not be easily replaced by active travel.[7]

Reducing emissions from transport will be crucial to meeting our overall net zero goals. Work is ongoing to create a better enabling environment for consumers in order to:

- encourage people to shift their transport choices from private internal combustion engine (ICE) car use to more sustainable modes of transport (known as modal shift),

- support active travel,

- increase the uptake of electric vehicles in Scotland and

- reduce the need for travel and encourage car sharing where it is needed.

These measures have been articulated as a national target to reduce the number of car kilometres driven annually by 20% from 2019 levels by 2030.[8] Audit Scotland, however, have recently highlighted concerns that the target will not be reached.[9] The Scottish Government remains committed to car use reduction and intends to set out a renewed policy statement detailing how it will work with the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA), regional transport and local authority partners to achieve this.

The Scottish Government has developed a hierarchy of sustainable transport in which walking, wheeling and cycling (active travel) are the most desirable modes of travel. The most sustainable forms of vehicle transport come from public transport provision. 396 million public transport journeys using these modes were taken in 2022,[10] but in order to achieve the level of modal shift needed to meet national climate ambitions, public transport uptake will need to increase significantly and consistently in the coming five to ten years to replace enough private car journeys to make a meaningful impact on emissions.

This makes understanding the ongoing consumer experience of different public transport modes crucial to Scottish Government meeting its climate goals. If consumers are to make greater use of public transport in future in a way that works well for then it is important that the public transport network delivers high quality outcomes on the key issues that matter to consumers. This includes:

- good access to affordable and reliable services,

- a choice of modes and providers where possible,

- clear, accurate, useful, easy to find information on service provision

- robust redress mechanisms for resolving problems and complaints

- the opportunity to have their say on how services are delivered.

The Scottish Government have set a target to phase out sales of new petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030,[11] in line with the target set by the new UK government.[12] However, while private car use is less environmentally sustainable than public transport use or active travel, transport policy makers recognise that private car use cannot easily, quickly, or fairly be phased out for many consumers, especially in rural areas. As a result, the target to phase out petrol and diesel cars and vans is accompanied by the UK Zero Emission Vehicle Mandate which sets progressively higher interim targets for new vehicle sales.[13]

The CCC most recently reported on the Scottish Government’s progress towards meeting its climate goals in March 2024. The report highlighted transport and transport-related emissions as a key area for concern, with recent rises in overall emissions primarily driven by an increase in surface transport emissions.[14] The CCC estimated that in order to achieve current targets, transport emissions in Scotland would have to drop by 44% by 2030, meaning that the rate of annual emission reduction must increase by almost a factor of four.[15]

This will be challenging to achieve, and any success in doing so would be significantly predicated on encouraging consumers to switch from petrol and diesel cars to active travel, public transport, or - in areas with poorer active and public transport connections - to EVs. This will require significant policy interventions to simplify fares, enhance services, and improve cost-competitiveness when measured against car travel in order to enable consumers to make a modal shift.[16]

The CCC also commented on progress related to EV policy and targets. While they described the delivery of charge points in Scotland as ‘on-track’, they also identified a need to treble the pace of the roll-out in order to deliver Scotland’s share of the required UK charging infrastructure and a need to improve reliability of the existing charging network.[17]

4. The Legislative and Policy Background

Each year, the Scottish Government publishes updated emissions envelopes for the transport sector under the Climate Change Plan (CCP). These dynamic annual targets reflect the maximum emissions that can come from the sector in order for Scotland to remain on track in meeting its wider net zero targets. Emissions from transport routinely exceed the sector envelope,[18] only being within the envelope in 2020, where the report noted that “the extraordinary impact of a pandemic” allowed the sector to meet the target. This reflects the scale of the reduction needed.[19]

In light of these challenges, the Scottish Government are pursuing a range of different policy approaches to encourage changes in transport behaviour, and these could have substantial impacts for future consumers.

In 2022, Transport Scotland and the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities jointly published a draft routemap for reducing car use by 20% by 2030.[20] This outlined a number of potential approaches to reducing car use, including measures to discourage car use and help people switch modes, encouraging car-sharing, and reducing the need for travel generally.

Transport Scotland published the Fair Fares Review in early 2024[21] , setting out plans to improve the availability, accessibility, and especially the affordability of public transport across bus, rail, ferry, tram, and subway. The Review committed to a number of measures to improve public transport systems for consumers , including a trial of flat fares for buses, expanded concessionary benefits for ferry users, and developing a national and/or regional integrated ticket and fare structure.

In February 2025, the Scottish Government published a consultation on a draft just transition plan for the transport sector in Scotland.[22] This set out the transport sector’s significant contribution to emissions in Scotland and presented a number of planned outcomes and broad principles for a just transition to more sustainable transport behaviours in Scotland.

It is the parallel aim of both UK and Scottish Governments to encourage EV use for those who may struggle to make such changes. Of the around 2.4m private cars in Scotland at the end of March 2024, only 34,254 were fully electric, highlighting there is still some way to go.[23] Scottish Government published in December 2024 its Draft Electric Vehicle Public Charging Network Implementation Plan,[24] setting out plans for ’a public EV charging network that is comprehensive and convenient, meets the needs of all users, is grown with private investment, powered by clean, green energy and complements the wider sustainable transport system.’ A recent Consumer Scotland report on the consumer experience of EV ownership has highlighted access to charging, especially for those without access to domestic charging, as a priority for consumers and for ongoing EV policy.[25]

If successful, the overall impact of the initiatives described above could support the delivery of transport services that are more convenient, reliable, integrated, and intuitive for consumers to use.

However, Audit Scotland has highlighted a number of significant issues in relation to the Scottish Government’s work on sustainable travel, finding that there is no evidence of a significant and sustained modal shift away from private car use to more active forms of transport.[26] The Auditor General noted a need for stronger leadership and clearer governance arrangements, in order to ensure clarity of delivery arrangements around the 20% car km reduction targets. This clarity has been, and will continue to be, difficult to generate without a detailed delivery plan. As a result, it is unclear which interventions will have the most impact or deliver the best value for money and there have been difficulties in monitoring and scrutinising progress. There is a need to bring together existing information to provide an overview of how public transport and active travel activities contribute to the overarching goal of reducing car use. Spending to support the delivery of car reduction initiatives was also found to be complex, fragmented and lacking transparency.

In addition, it was noted that meeting the 20% car km reduction target would require implementing measures to reduce car use which are difficult and potentially unpopular.[27] Measures to discourage car use, however, such as making driving more expensive, could have negative impacts for those consumers with greater reliance on car use, especially those consumers who are disabled or who live in rural areas. Action to mitigate the negative impacts of any such changes for consumers, and especially those in vulnerable circumstances, is therefore essential.

5. About this report

In 2023/2024 Consumer Scotland significantly expanded our net zero and climate change evidence base. Over the course of six research projects, using a range of research methods, we examined in detail consumers’ attitudes, experiences, beliefs, behaviours and perceptions related to the transition to net zero and wider climate change adaptation and mitigation.

This report draws primarily on the findings from two of these projects:

- A quantitative survey of consumers’ general attitudes to net zero, and

- A qualitative project which explored consumers participation in the transition to net zero.

In September 2024 we published a report summarising the findings of these two projects.[28] The key findings related to consumers’ perceptions of and engagement with net zero in general were:

- Levels of consumer concern about climate change are not resulting in action that matches the pace and scale of change required

- Cost and convenience remain the key factors in driving consumer purchasing decisions. The sustainable actions that consumers do take are often more influenced by ease and cost than by environmental benefits

- Consumers are seeking clearer leadership and guidance in order to enable them to make the choices that will help to tackle climate change

These broader findings about current consumer attitudes and engagement with net zero, and consumers’ ability and willingness to make changes in their habits and behaviours, provide useful context for this report on attitudes to transport choices and habits.

Consumer Scotland also recently published a report on the consumer experience of EVs in Scotland, and how their uptake fits into wider Scottish Government strategies on climate change adaptation and mitigation.[29]

This report draws primarily on the findings of these research projects, and presents our key findings about consumer attitudes regarding public transport and the adoption of more sustainable transport habits. It highlights the extent to which specific transport behaviours are undertaken that reduce consumers’ emissions, as well as the factors that act as barriers for some to adopting alternatives to petrol and diesel cars. The report also draws on more granular demographic-based data to help understand why different transport choices are more accessible for some groups, and to help identify potential groups who face specific barriers to sustainable transport choices.

Based on this analysis, we identify a number of key conclusions and recommendations relating to policy on public transport services and the consumer transition to EVs which should be addressed in the sector’s transition toward net zero, in order to help deliver positive consumer outcomes.

6. Key Findings Related to Consumer Attitudes and Behaviour Related to Transport Choices

Consumers want to make more sustainable transport choices, but this interest is not translating into behaviour change

Consistent with the findings on broader consumer attitudes to sustainable choices, our survey research, conducted by YouGov, and undertaken between February and March 2024, showed that a majority of consumers in Scotland (65%) would like to reduce their carbon emissions by using more environmentally sustainable transport methods.[30]

Chart 1: Two thirds of consumers would like to reduce their transport-related carbon emissions

The proportion of survey respondents stating they would or would not like to reduce carbon emissions from their transport methods

Source: Consumer Scotland – Consumer perceptions of and engagement with the transition to net zero

Base: 2,062

These attitudes, however, have not clearly translated into behaviour change. Transport Scotland’s latest statistics indicate that usage of public transport services is recovering from the impact of the pandemic and increased by 15% in 2023-2024, but is not yet at pre-pandemic levels.[31]

This lack of behavioural shift towards more sustainable transport choices indicates that further action is required to create a more enabling environment for consumers, making it easier and more attractive for them to make more sustainable transport choices.

Although consumers state they wish to reduce the emissions associated with their travel journeys, our qualitative research, conducted by Thinks Insight & Strategy during March 2024,[32] found that cost and convenience were seen by consumers as the most important factors in their transport choices. Our survey research showed that, for key sustainable transport changes, environmental concerns were not the main factor in consumer decisions about transport choices:[33]

Chart 2: Environmental concerns are not usually the main reason that consumers make sustainable transport decisions

The percentages of participants who took action to reduce their transport emissions, and the proportions of whether environmental concerns were a factor in their choice.

Source: Consumer Scotland – Consumer perceptions of and engagement with the transition to net zero

Base: 2,062

However, higher numbers of respondents reported that environmental concerns were a secondary motivator for undertaking each behaviour,[34] as shown in chart 2. This suggests that environmental concerns are still relevant factors for consumers. For these consumers, messaging around the environmental benefits of more sustainable transport behaviours may not be powerful enough alone to inspire change. Where information about co-benefits can be combined with improvements to the cost and convenience of services this is more likely to facilitate an increase in the uptake of sustainable transport options.

Issues around availability and underlying infrastructures can make public transport hard to access for some

Participants in our qualitative research described public transport as being ‘increasingly unreliable where it is available, and unavailable in some areas...’[35] Our research also suggested that, in rural and island areas especially, limitations of infrastructure and issues around accessibility and availability may mean that changing transport behaviours feels ‘out of reach’ for some consumers.[36]

This is mirrored in the findings of our quantitative research, where 71% of those in urban areas listed lack of availability as a top three barrier to choosing public transport, while (78%) of those in rural areas cited it.[37] As a result, participants in both our quantitative and qualitative research indicated that public transport infrastructure and service improvements were necessary for sustainable choices to be even considered viable, especially in rural areas.[38]

“Public transport is almost non-existent in our local area. We would have to drive to the closest ‘bus stop’ which is around 5 miles away.” (Male, Eco-reactive, Rural, 56-64)

Barriers to choosing sustainable transport options like this, as well as such as concerns around cost, convenience, availability, and safety of services mean that private car use continues to be the default choice for many consumers.

Lack of information provision about sustainable alternatives to car use can also influence decisions

Consumers who want to make more sustainable transport choices may not know how they can do this. Our survey research found that 17% of consumers do not know how to reduce their transport carbon emissions, while 15% didn’t think their actions would have an impact.[39] This lack of awareness may partly explain why a reported interest in reducing transport emissions is not translating into behaviour change at the required rate to meet net zero targets. Our qualitative research also suggested that sustainable behavioural changes can be strongly influenced by the behaviour of peers,[40] and so a perception that services are unavailable, unaffordable or unlikely to meet consumer needs among the wider consumer base may further reduce the potential for consumers to pursue more sustainable transport habits.

Transport behaviours are often habitual and ingrained, especially in rural areas, and this can be hard to change

A key finding from our qualitative research was that transport is a sector where consumer choices are likely to be deeply ingrained, based on established habits tied closely to family and work commitments.[41] People find what works for them, which is generally the most affordable and readily available option for their journey, which may then become routine.[42] These habits, and the factors that contribute to them, are hard to change. This may present challenges to the adoption of more sustainable travel options, even if such options were to become more affordable and convenient, when private car use is ingrained.[43]

“I don’t want to reduce my standard of living by giving up my car... I’d need an electric or hydrogen car that can do 500 miles on a tank / charge, didn’t cost the earth, and didn’t change its value.” (Male, Eco-reactive, Suburban, 50-65)

Where consumers live also plays a significant role in transport behaviours. Active and public transport choices are often more accessible for consumers in urban areas while driving is more common in rural and island communities.[44] Scottish transport statistics support this, and show 56% of people in large urban areas had used the bus in the previous month, compared to 17% in remote rural areas.[45]Meanwhile, as of 2023, 86% of those in remote rural areas had full driving licences compared to 62% in large urban areas, with Glasgow having the lowest rate of vehicles licenced per capita.[46] The reasons for this are clear and largely practical. The lower population densities in rural areas make active travel infrastructure and commercial bus routes less easy to create and sustain than in urban areas.[47] As a result, driving is more often unavoidable in rural areas.[48] As using EVs still allows consumers to drive with reduced emissions, this suggests any approach to decarbonising car use in rural areas will need to support positive consumer engagement with EVs use as well as enhancing the role of sustainable public transport in rural and island communities.

7. Behaviour Choices that Reduce Emissions

We asked survey respondents what actions they had undertaken that reduced their transport emissions. Where consumers reported taking action, the most common action was using public transport rather than a car, which 69% of respondents reported.[49] The other key behaviours noted were:

- 66% choosing active travel over car use for travel to work, education or leisure settings

- 51% reducing their car mileage

- 37% working or volunteering from home[50]

Our research did not go into detail regarding the frequency of these behaviours and choices, but this does suggest that some consumers are currently able to make changes in behaviour. The data from our survey research has also allowed us to examine demographic trends within each of these key behaviour choices.

Choosing Public Transport Options Over Car

Certain demographic groups were more likely than others to reduce their transport emissions by choosing public transport over using their car. 73% of those in urban areas reported this behaviour, compared to 61% from rural areas.[51] In Glasgow and Lothian especially, reporting of this behaviour was significantly higher than in other Scottish regions.[52] This supports the view that where there are less developed public transport networks, public transport is less likely to be accessible for consumers as an alternative means of travel. In urban areas, and especially in Edinburgh and Glasgow where there are more significant public transport networks available, consumers are more likely to be able to consider using public transport.

There was also a statistically significant difference between respondents in different income categories. Those with the highest household incomes (£60,000+) were more likely (75%) to reduce emissions by using public transport than those with the lowest incomes (less than £20,000), of whom 67% reported doing so.[53] Evidence from our briefing on concessionary fares[54] suggests that those on lower incomes are more dependent on public transport in the first place and so opportunities for behaviour change may be more accessible to higher earners.

Our survey responses also indicate that choosing public transport may be easier for people who don’t report disability. 70% of those who didn’t report any disability reported choosing public transport over car use, compared to 60% of all disabled people, and 52% of disabled people with significant limitations.[55] This indicates that accessibility issues can act as a barrier to disabled people choosing public transport and reducing their emissions as a result.

Trying active travel

Disability, and especially disability that causes significant limitations, may also be a barrier to trying active travel. While 67% of those who did not report a disability reported trying active travel, only 57% of disabled people, and 55% of those who reported having significant limitations due to their disability reported this.[56] There are a number of reasons why this could be the case. Key issues may include active travel infrastructure and routes not being accessible, or potentially not feeling safe when travelling alongside cars and bicycles.[57] For some disabled people, active travel may continue to feel out of reach until infrastructure evolves to address these concerns.

There were also geographic differences in relation to active travel behaviours, with 67% of those in urban areas reporting trying active travel compared to 60% in rural areas.[58] Both Glasgow and Lothian again had significantly higher rates of active travel reporting than other regions.[59] As with public transport, this may suggest greater provision of active travel infrastructure in more urban locations.

Working or volunteering from home

Working or volunteering from home is another behaviour people can adopt that reduces their emissions. Our research found very similar demographic trends here to those of participants saying they would like to reduce their transport emissions and also those stating they have already changed their behaviour around transport. There is a clear and consistent inverse correlation between age and the likelihood of working from home with 22% of 55+ year olds reporting working from home compared to 42% of 35-54 year olds, and 50% of 16-34 year olds.[60]

There are also clear correlations between higher incomes and the likelihood of working or volunteering from home with 20% of those with household incomes of less than £20,000 doing so, rising to 57% of those with incomes of £60,000 or more. This could be due to recent ONS findings that higher paid jobs were more conducive to home working as they generally required less physical activity and face-to-face interaction.[61]

Our research also found that people who did not report having a disability (38%) were more likely to report working or volunteering from home than disabled people (29%).[62] The ability for disabled people to avoid a transport network which many find to be less accessible,[63] as well as a range of other benefits to working from home[64] may make this finding seem counter-intuitive. Given, however, that home working is generally more available to those with higher-paying jobs,[65] and that disabled people are more likely to be employed in low-paying jobs , home-working opportunities are currently less available to disabled workers than non-disabled workers. Recent ONS data also shows that nearly half of disabled people (47%) reported not being able to home-work at all,[66] with research also showing that disabled people are not always provided with necessary adjustments to do so.[67]

Finally, with regards to people’s ability to volunteer from home, while it is true that opportunities to volunteer from home have increased since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, over two-thirds of opportunities require travel to physical hosts.[68]In general, patterns for volunteering match those for employment, with people with higher incomes being more able and likely to volunteer than those with lower incomes,[69] and disabled people facing similar challenges when trying to volunteer from home[70]as to when they try to work from home.

8. There are barriers to consumers making sustainable transport choices

Consumers who did not choose public transport options cited a number of reasons. In our quantitative research, participants were asked to rank the reasons they did not choose transport methods with a lower environmental impact. As is shown in the chart below, the main reasons given were a lack of availability of options (73% ranked as a top three reason) and the cost of options (70%), with time taken to use them (53%) and range capabilities (43%) also commonly cited.[71]

Chart 3: Lack of availability and cost are the most common reasons consumers don’t choose transport options with a lower environmental impact

The proportions of participants to cite different reasons as a barrier to adopting transport habits with a lower environmental impact, and whether it was their primary barrier, or the second or third most impactful barrier

Source: Consumer Scotland – Consumer perceptions of and engagement with the transition to net zero

Base: 1,340

The same findings were evident from our qualitative research, where consumers who don’t use sustainable travel methods told us that services are not available, are too expensive, and take too long.[72] Tackling these challenges is important when considering how services need to improve to enable consumers to make sustainable travel choices.

Service availability

Transport Scotland‘s data estimates that to achieve a 20 per cent reduction in car kilometres by 2030, public transport capacity would need to increase by 222%.[73] In this context, it should be noted that public transport services available to consumers in Scotland are not increasing. Rail services, in terms of route kilometres operated had not increased between 2020 and March of 2024,[74] though the Levenmouth railway did become operational again after that time.[75] Meanwhile, bus services have been in long-term decline, with around 44% of registered bus routes being cut since 2006.[76]

Lack of service availability was consistently noted as a barrier to public transport in both our qualitative and quantitative research, with some consumers attributing less sustainable transport behaviours to a lack of appropriate infrastructure and services.[77] The two regions where participants most commonly listed availability of service as a barrier were the Highlands and Islands (81%) and Glasgow (79%).[78] This shows that the issue of service availability is a broadly nationwide one, but also that availability issues for public transport can manifest for different reasons.

In the Highland local authority, it is recognised that public transport coverage is significantly limited, in part due to the geographical makeup of the area.[79] Glasgow, meanwhile, has the third largest public transport network in the UK, but also has the largest population in Scotland spread across a wide urban area.[80] In this context, a large and diverse public transport network still struggles to meet the needs of consumers, causing issues with availability and convenience of service.[81]

“For a year we didn’t have a bus service. Even now it doesn’t go to the train station, so I think an integrated transport network would be amazing.” (Female, Eco-passive, Urban/rural, 56+.)

Our survey research also found that people in the most deprived areas of Scotland (based on the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation) more commonly listed lack of availability as a barrier to choosing public transport. This is perhaps not surprising given that the time taken to travel to key locations using public transport forms part of the SIMD assessment.

Cost

Cost was cited by survey respondents as a major barrier to choosing sustainable behaviours across all of the consumer markets highlighted in our net zero research, including transport. A higher proportion of people in age brackets not eligible for various concessionary fares listed the cost of public transport as a barrier.

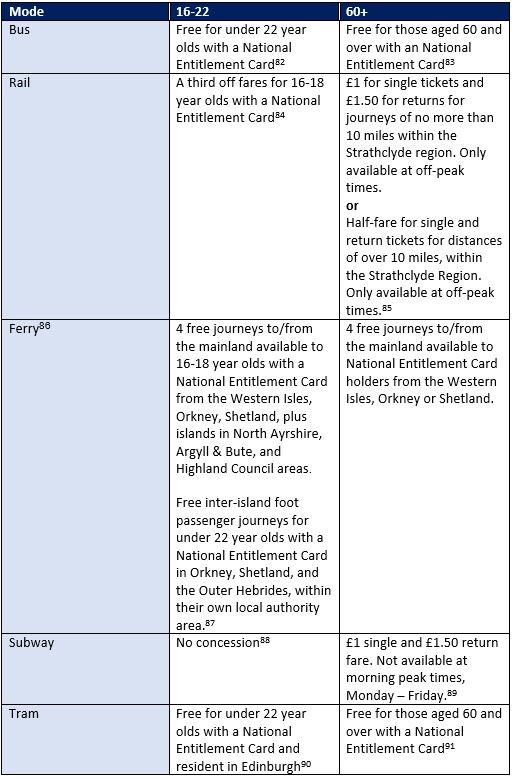

Chart 4: Concessionary fares in Scotland are not consistent across ages or modes.

The concessions available to people in different age brackets across all modes of public transport.

Although the age brackets used in our research do not match up precisely with the age ranges of eligibility for concessionary fares in Scotland, our analysis does indicate a correlation between those ineligible for concessionary fares and those who cited cost as a barrier to choosing public transport. Analysis found that 78% of respondents aged between 25 and 54 (i.e. entirely ineligible for age related concessionary fares) cited cost as a top three barrier for choosing public transport, with 38% identifying it as the top barrier. This compared to 61% of respondents potentially eligible for concessionary fares.[92]

Consumer Scotland’s 2024 report on concessionary fares for bus travel[93] found insufficient evidence to suggest that concessionary fares are a primary influence on modal shift from car to bus use for those eligible to receive them. Our survey research also does not allow us to draw conclusions about whether and how concessionary fares influence modal shift towards public transport broadly. However, the data does show that cost across public transport modes is a significant barrier for consumers generally and especially so for consumers ineligible for concessionary fares.

8.10 Perhaps surprisingly, significantly more participants with incomes of £60,000 and above (76%) rated cost as a barrier to choosing public transport than those with incomes below £20,000 (63%).[94] The difference may be explained by the levels of choice consumers have in their travel habits. As our report on concessionary travel for buses found, those on lower incomes are less likely to own a car and so are more reliant on bus use. More wealthy consumers, who have greater choices between car use and public transport, may be more responsive to lower fares.[95] In terms of addressing net zero goals, reducing cost appears to have an important role to play in supporting consumers’ public transport use.

Time Taken

53% of participants in our quantitative research listed the time taken to complete journeys using alternatives such as public transport or active travel as a barrier to choosing alternatives to car use.[96] As with issues around cost, our survey data suggests that those with higher incomes are most influenced in their decisions by the length of time that public transport journeys may take.

Only 36% of those survey respondents with household incomes less than £20,000 listed the time taken to use more sustainable travel options as a barrier to utilising them, compared to 55% for those with a household income of £20,000-£39,999 or £40,000-£59,999, and 60% for those with £60,000 and above.[97]

This reiterates that those with higher incomes may have a greater ability to choose whether or not to use more sustainable transport options, compared to those on lower incomes.

Accessibility

Amongst our survey respondents, 38% of those with a disability or long-term health condition ranked issues related to their health and accessibility as a reason to not use public transport, with 16% ranking it first.[98]The findings of a recent study by Bus Users UK may help explain why this could be the case. Their report found that bus stops, bus design, audio and visual information on buses, and the behaviour and attitudes of both drivers and passengers can affect the accessibility of bus travel for disabled people and those with long-term health conditions.[99] Other research also indicates that access to rail services,[100] ferries,[101] and the Glasgow subway[102] can pose significant issues. Disabled consumers may face real challenges when using public transport and improving the overall experience and accessibility of travel will reduce barriers to choosing public transport options.

Safety

Worries about safety were cited by 11% of our survey respondents as one of the top three reasons they didn’t choose public transport.[103] Our survey does not explore these concerns in further detail, but our findings are consistent with other research that identifies groups potentially more likely to consider safety when choosing their transport method. Recent work specifically on women’s and girl’s experiences on public transport from Transport Scotland found that women travelling on public transport sometimes felt the need to maintain a state of ‘vigilance’ due to fear of harassment, assault, or anti-social behaviour.[104]Our survey research also showed 13% of females listing safety concerns as a barrier to travel, compared with just 9% of males.[105] Our survey research also suggested that considerations of safety may be an increasing barrier to public transport usage as consumers get older. Although the differences were not statistically significant, the smallest proportion of respondents citing this as a barrier was in the 16-34 year old age group (9%). The proportion increased with age, with 14% for those aged 55 and above listing it as a top three barrier.[106]

Other research has noted that disabled consumers have also shared concerns around safety, especially in relation to travelling at night or from unstaffed stations.[107] Similarly, existing research indicates that other groups may have safety concerns when travelling.[108] Concerns around safety are potentially a significant barrier to making sustainable transport choices, and the issues experienced by consumers must continue to be investigated and addressed.

9. Perceptions of Electric Vehicle use from broader Consumer Scotland research

For some consumers, their circumstances will result in a higher reliance on car use, even if active travel and public transport services are improved. Private cars are at the bottom of the hierarchy for sustainable transport, but Electric Vehicles (EVs) do produce fewer emissions than petrol and diesel vehicles throughout their lifespan if they are used for a long enough time,[109] and therefore have a role to play in achieving net zero targets.

Consumer Scotland’s qualitative research sought the views of consumers towards EVs and EV usage. While general awareness of net zero policy was low, it was high in relation to the target to phase out sales of internal combustion engine (ICE) cars by 2030.[110] Despite the high awareness however, 95% of the cars currently registered for the road in Scotland are still internal combustion engine (ICE) cars, and they account for around 68% of new vehicle registrations.[111] A recent report by Which? showed only 6% of non-EV drivers would consider buying an EV as their next vehicle.[112] Which? also reported that rates of non-EV drivers being unwilling to consider buying an EV nearly doubled from 20% in June 2021, to 39% in June 2024.[113] Given this, meeting the target to phase out ICE cars will require significant behavioural change from consumers.

Our research found divergent attitudes regarding EV use. Those consumers keen to improve the sustainability of their transport behaviours were more open to owning EVs and were supportive of the environmental benefits doing so can bring, such as reducing emissions from driving as well as the public health benefits such as cleaner air.[114] Those less actively motivated by environmental concerns, however, are more likely to consider EVs expensive and inconvenient; believe EV charging infrastructure, especially in rural areas, is too under-developed; and potentially be sceptical of their environmental benefits given perceived manufacturing emissions and shorter lifespans of EVs.[115]

“I don’t truly believe that electric cars are the best solution. I have a well-maintained old car. The average electric vehicle takes on average eight years to break even on the manufacturing emissions, so it’s just a money maker as far as I’m concerned, but it looks like we’re all being forced to go in that direction.” (Male, Eco-passive, Urban, 36-45)

Consumer Scotland recently published research findings specifically focused on the experience of EV ownership in Scotland, which mirrors some of these views, especially related to charging infrastructure.[116] While the overall picture from the research was that EV owners were very positive about their vehicles, findings were less positive about supporting infrastructure, particularly related to charging.

The research focused on current EV drivers, but also considered the views of those considering purchasing an EV. More than three quarters (78%) of those considering purchasing an EV reported that they worry they will not be able to charge their vehicles when out and about. The proportion did fall for those who were driving an EV, but around half (51%) still reported the concern. The reliability of existing public charging infrastructure also appears to be a frequent issue for EV drivers, as 75% of EV drivers reported at some point having to use a different charging point to the one they had originally intended to use.[117] For those entirely reliant on public charging, i.e. reported they did not have access to at home charging, the proportion was 60%.[118]

A similar pattern was noted for concerns with running costs. These were reported by 31% of those considering purchasing an EV. This fell to 15% for current EV drivers. It was, however, significantly higher among those unable to charge at home with 33% reporting this concern. Similarly, those unable to charge at home were more likely to report that running costs were higher than expected (38% compared to 14%).[119] This disparity is of particular concern given that 37% of Scotland’s households are estimated to live in flats,[120] and will therefore be reliant on public charging for electric vehicles, something that we estimate will not be a choice in around twenty years’ time.[121]

10. Key messages for policy and decision makers

Sustainable transport options must be more affordable and better value for money if targets are to be met

Our research found that cost is a primary factor in determining consumer travel habits. It is also one of the most common barriers cited by those who are not currently making sustainable travel choices. If public transport options are considered more expensive or poorer value for money than car use, and people cannot afford to integrate these options into their daily lives, we will not succeed in meeting our climate targets.

We must identify where the cost of accessing of sustainable transport options is prohibitive to particular groups, and develop plans that address this by providing appropriate support.

Similarly, for those more reliant on cars, efforts must be made to find affordable solutions for those who cannot charge at home in order to deliver more equitable access to the benefits of electric vehicles.

Investing in the infrastructure underpinning sustainable transport options would enable more consumers to conveniently choose them

Convenience is the other primary factor that most frequently influences consumer travel habits. Participants in our qualitative research often noted that insufficient infrastructure and poor service provision contributed to a lack of accessible public transport options.

Significant work is needed to improve the public transport offering, across modes. Consumers must have access to convenient, and dependable, transport choices. Achieving this will require enhancing both public transport and active travel infrastructure to expand options and improve services.

We must ensure that the necessary investment to meet the challenges of the transition is delivered swiftly, with the costs of this shared fairly between current and future generations. There must be meaningful engagement with consumers at local and national level to ensure that sustainable transport options fit with people’s lives.

Improvements can take different forms. In some cases, it may be physical infrastructure, like new or revamped railway lines or stations, it may be the provision of bus prioritisation schemes or it could be investment in more bus routes that serve consumers in currently underserved areas. Investment in active travel infrastructure would also make it a more viable choice for some consumers. Any investment which improves public transport or active travel networks is likely to make these options more convenient for consumers and help enable consumers to change behaviour.

To enable drivers to switch from petrol and diesel vehicles to lower emission EVs, ongoing efforts to expand public charging infrastructure should continue, with a strategic focus on placing the right charge points in the right locations and improving their accessibility. Improving the availability and reliability of EV charging stations will help improve consumers’ experience of charging infrastructure, overcoming an important barrier to wider EV adoption and supporting more drivers to make the switch.

Consumers need meaningful and timely information which supports them to make sustainable choices

By developing consumer understanding of climate change issues and solutions, and providing a framework which makes implementing changes more straightforward, consumers can be empowered to take action with confidence, knowing they are doing the right thing, at the right time, and in the right way.

Our research shows that nearly two-thirds (65%) of consumers in Scotland are interested in reducing their emissions by altering their transport habits.[122] This highlights transport as an area with substantial potential for emissions reduction. Across government, the public sector, and business, there needs to be a concerted effort to ensure that consumers have the support and opportunity to participate in the transition to net zero, and that everyone can benefit from it.

Almost one third (32%) of consumers reported either not knowing how to make more sustainable transport choices, or that they did not think such changes would make a significant difference to our ability to meet emissions targets. This reveals a gap in tailored consumer information and support. We must improve consumer understanding of how they can contribute, and this must form part of a clear consumer-focused plan for change, articulated by government.

Work is also needed to highlight the broader benefits of sustainable transport choices for both consumers and communities. These benefits, often referred to as co-benefits, such as air quality improvements and other health benefits, will be central to encouraging more sustainable action by consumers and can help engage consumers who are not motivated by climate concerns alone. Public Health Scotland, for example, have highlighted the negative effects of high levels of private car use on public health, and considered how public transport and active travel options can alleviate this.[123] There have been recent media campaigns around these co-benefits, and we would welcome more of these types of initiatives in the future, with particular effort being put into reaching those groups most sceptical of public transport and active travel. Our qualitative research suggests that these broader health benefits may help consumers to understand the potential impacts of making more sustainable choices.[124]

Similarly, with regards to EVs, consumers’ awareness of the cost and convenience benefits of EV ownership could be improved. However, consumers would also benefit from easier access to accurate real-world information about practical matters such as ranges, and the costs of different charging methods.

Sustainable transport options must be available for all, though these options may differ by location

Our research highlighted that transport habits are closely linked to daily routines around work, education, and childcare. This means that if consumers are to shift transport behaviours, the sustainable alternatives must effectively meet consumers’ needs.

Transport behaviours may be heavily influenced by where consumers live. Consumers in more densely populated urban areas may have more access to, and be more likely to use, active travel or public transport options. Consumers in rural areas, where distances from home to work, school, retail, or social spaces are generally larger, and the availability of sustainable travel options may be lower, are likely to be more dependent on car use.

A mixture of improved public transport options, active travel routes, and EV charging infrastructure will be needed for consumers nationwide. Policy makers should take these place-based realities into account when developing future strategies, focussing on the most appropriate sustainable options being available to consumers wherever they live.

More work is required to make public transport accessible and inviting for all

For too many consumers, public transport is hard to access or does not feel safe. Concerns about accessibility or safety can affect a broad range of people, and large proportions of the population. If consumers are concerned about their ability to safely access public transport, they are more likely to feel secure travelling by private car. This constitutes a significant challenge in meeting modal shift and wider emissions targets.

While work has been undertaken related to the accessibility of different public transport modes, and about issues of safety – especially for women and girls – on public transport, issues and perceptions about the accessibility and safety of public transport persist.

There is a need for a greater understanding of the issues that specific groups encounter when using public transport. This must be progressed through engagement with relevant groups representing consumers, and especially those in vulnerable circumstances.

11. Recommendations

1. Transport Scotland should design and deliver a new consumer engagement programme to support the implementation of the Just Transition Plan for Transport in Scotland.

This should identify priorities and inform the design of services so that they meet the diverse needs of consumers across the country. This includes the needs of consumers with a range of employment types, household income, family statuses and characteristics of potential vulnerability such as disability.

2. The Scottish Government should work to make public transport safer and more accessible for consumers.

Transport Scotland should address barriers to public transport, particularly for groups with reported safety or accessibility concerns, such as disabled people and women and girls. This work should cover all modes of transport, and its findings should form the basis of a future action plan to combat these issues.

3. Investment in services and infrastructure must be based on agreed understanding of current provision and targeted to meet consumer need.

Transport Scotland should work together with stakeholders to compile a comprehensive assessment of which areas in Scotland have sufficient active travel and public transport services. This should inform decisions on prioritisation of future services and help target potential investment decisions that could support improved public transport usage.

4. Scottish Government should continue to promote the benefits of sustainable travel to consumers.

As part of its wider work to promote net zero messages, the Scottish Government should continue to specifically highlight the contribution that consumer transport choices can make to meeting our emissions targets. They should also highlight the wider co-benefits of sustainable travel choices. Particular effort should be put into reaching those groups most sceptical of public transport and active travel to maximise impact.

5. Transport Scotland and the Scottish Government must ensure that all major plans to reduce emissions in the transport sector clearly explain the expected contribution from each key action and allocate responsibility, and budget, for delivering work to meet targets.

When implementing the National Transport Strategy and other delivery plans, the purpose and impact of each output should be clear to consumers. They should also clearly identify how each measure will improve consumer experiences of public transport and/or contribute to transport-related net zero targets.

6. Transport Scotland and the Scottish Government should carry out impact assessments on policies to reduce car use and promote more sustainable choices, to identify where mitigations need to be put in place to support consumers, as proposed by Audit Scotland. [125]

These assessments must be available for scrutiny early enough in the design process to facilitate high quality engagement from consumers and consumer groups. Where impacts on specific groups are identified, for example arising from car demand management measures, specific mitigation measures should also be developed and costed.

7. Transport Scotland should take a leading role in ensuring its Vision for public EV charging is achieved, by developing a clear plan for how it will monitor and drive delivery of the actions identified in its draft Vision Implementation Plan.

Transport Scotland has published a draft Implementation Plan for its Vision for Scotland’s Public Electric Vehicle Charging Network, which emphasises the role of stakeholders and private investment for achieving its outcomes. Transport Scotland, however, has an important role to play in ensuring that the Vision is achieved, and should develop a clear plan for how it will support delivery, for example, through monitoring and coordinating activity. Specific actions should be pursued to ensure the vision is realised for consumers in rural communities, where for many, EVs may be the only practical sustainable transport option.

12. Endnotes

[1] Consumer Scotland (2024), Consumer Experience of Electric Vehicles in Scotland, available at en24-02-low-carbon-technologies-electric-vehicles-publications-consumer-scotland-insight-report-clean.pdf

[2] Consumer Scotland (2023) Strategic Plan 2023-2027. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/impact-assessment/2023/06/circular-economy-scotland-bill-equality-impact-assessment/documents/circular-economy-scotland-bill-equality-impact-assessment/circular-economy-scotland-bill-equality-impact-assessment/govscot%3Adocument/circular-economy-scotland-bill-equality-impact-assessment.pdf https://consumer.scot/publications/strategic-plan-2023-2027-html/#:~:text=Consumer%20Scotland%20seeks%20to%3A%201%20enhance%20understanding%20and,economy%20by%20improving%20access%20to%20information%20and%20support

[3] Consumer Scotland (2024) Work Programme 2024-25. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/t13bxnd2/consumer-scotland-work-programme-2024-2025.pdf

[4] Committee on Climate Change (2025) The Seventh Carbon Budget: Advice for UK Government, accessible at The Seventh Carbon Budget

[5] Climate Xchange (2023), How do we reliably transport people and goods without emissions?

[6] ibid.

[7] Audit Scotland (2025) Sustainable Transport available at https://audit.scot/uploads/2025-01/nr_250130_sustainable_transport.pdf

[8] Transport Scotland (2022), A route map to achieve a 20 per cent reduction in car kilometres by 2030, available at https://www.transport.gov.scot/publication/a-route-map-to-achieve-a-20-per-cent-reduction-in-car-kilometres-by-2030/

[9] Audit Scotland (2025) Sustainable Transport available at https://audit.scot/uploads/2025-01/nr_250130_sustainable_transport.pdf

[10] Transport Scotland (2024), Scottish Transport Statistics 2023

[14] The Climate Change Commission (2024), Progress in Reducing Emissions in Scotland: 2023 Report to Parliament

[15] Scotland’s 2030 climate goals are no longer credible - Climate Change Committee (theccc.org.uk)

[16] The Climate Change Commission (2024), Progress in Reducing Emissions in Scotland: 2023 Report to Parliament

[17] The Climate Change Commission (2024), Progress in Reducing Emissions in Scotland: 2023 Report to Parliament

[18] Scottish Government (2024), Climate Change Monitoring Report 2024, accessible at: Climate change monitoring report 2024 - gov.scot

[19] Scottish Government (2023), Climate Change Monitoring Report 2023, accessible at: Climate Change Plan Monitoring Report 2023: Transport - Climate change monitoring report 2023 - gov.scot

[20] Transport Scotland (2022), Reducing Car Use for a Healthier, Fairer and Greener Scotland, accessible at: A route map to achieve a 20 per cent reduction in car kilometres by 2030

[21] Transport Scotland (2024), Fair Fares Report, accessible at: Fair Fares Review

[22] Scottish Government (2025), Just Transition: draft plan for transport in Scotland, accessible at Just Transition: draft plan for transport in Scotland - gov.scot

[25] Consumer Scotland (2024), Consumer Experience of Electric Vehicles in Scotland, available at en24-02-low-carbon-technologies-electric-vehicles-publications-consumer-scotland-insight-report-clean.pdf

[26] Audit Scotland (2025) Sustainable Transport available at https://audit.scot/uploads/2025-01/nr_250130_sustainable_transport.pdf

[27]Audit Scotland (2025) Sustainable Transport available at https://audit.scot/uploads/2025-01/nr_250130_sustainable_transport.pdf

[28] xm24-02-consumer-perceptions-of-and-engagement-with-the-transition-to-net-zero-final-report.pdf

[29] Consumer Scotland (2024), Consumer Experience of Electric Vehicles in Scotland, available at en24-02-low-carbon-technologies-electric-vehicles-publications-consumer-scotland-insight-report-clean.pdf

[30] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-surveyyougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[31] Transport Scotland (2025), Scottish Transport Statistics 2024, accessible at Scottish Transport Statistics 2024 | Transport Scotland

[32] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the

transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[33] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-surveyyougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[34] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-surveyyougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[35] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the

transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[36] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the

transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[37] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 30). Available at:

[38] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the

transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[39] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-surveyyougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[40] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the

transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[41] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the

transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[42] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the

transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[43] Transport Scotland (2022), A route map to achieve a 20 per cent reduction in car kilometres by 2030. Available at A route map to achieve a 20 per cent reduction in car kilometres by 2030 | Transport Scotland

[44] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the

transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[45] Transport Scotland (2025), Scottish Transport Statistics 2024, accessible at Scottish Transport Statistics 2024 | Transport Scotland

[46] Transport Scotland (2025), Scottish Transport Statistics 2024, accessible at Scottish Transport Statistics 2024 | Transport Scotland

[47] Institute for Public Policy Research (2022), Fairly Reducing Car Use In Scottish Cities: A Just Transition For Transport For Low-income Households. Available at https://ippr-org.files.svdcdn.com/production/Downloads/fairly-reducing-car-use-in-scottish-cities-july-22.pdf

[48] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the

transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[49] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-surveyyougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[50] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-surveyyougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[51] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 26). Available at:

[52] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 26). Available at:

[53] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 26). Available at:

[54] Consumer Scotland (2024), Consumers and the National Concessionary Travel Schemes, accessible at cm24-04-ncts-evidence-review-publication.pdf

[55] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 26). Available at:

[56] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 26). Available at:

[57] Transport Scotland (2023) Social and Equality Impact Assessment - Cycling Framework and Delivery Plan for Active Travel, accessible at Social and Equality Impact Assessment - Cycling Framework and Delivery Plan for Active Travel | Transport Scotland

[58] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 26). Available at:

[59] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 26). Available at:

[60] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 26). Available at:

[61] Office for National Statistics (2020), Which Jobs Can Be Done from Home?, accessible at Which jobs can be done from home? - Office for National Statistics

[62] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 26). Available at:

[63] Motability Foundation (2022), The Transport Accessibility Gap, accessible at The Transport Accessibility Gap

[64] Trades Union Congress (2021), Nine in 10 disabled workers want to continue working from home after pandemic - TUC poll, accessible at Nine in 10 disabled workers want to continue working from home after pandemic - TUC poll | TUC

[65] Department for Work and Pensions (2024), The employment of disabled people 2024, accessible at The employment of disabled people 2024 - GOV.UK

[66] Office for National Statistics (2023), Characteristics of homeworkers, Great Britain, accessible at Characteristics of homeworkers, Great Britain - Office for National Statistics

[67] Work Foundation (2022), The Changing Workplace: Enabling Disability-Inclusive Hybrid Working, accessible at The changing workplace: Enabling disability-inclusive hybrid working

[68] NCVO (2023), Time Well Spent 2023, accessible at Volunteer participation - Time Well Spent 2023 | News index | NCVO

[69] Scottish Government (2024) Scottish Household Survey 2023, accessible at Scottish Household Survey 2023

[70] University of Salford (2024) Disabled volunteers at risk of exclusion due to ‘digital divide’, accessible at Disabled volunteers at risk of exclusion due to ‘digital divide’ | University of Salford

[71] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024. Available at: Consumers and the National Concessionary Travel Schemes (HTML) | Consumer Scotland https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-surveyyougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[72] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the

transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[73] Transport Scotland (2024), Fair Fares Report Supporting Paper 2: Case for Change, accessible at: Themes emerging | Transport Scotland

[74] Office of Road and Rail (2024), Train Operating Company key statistics: Scotrail, accessible at Train Operating Company Key Statistics 2023-24 ScotRail

[75] Scotrail (2024), The railway has returned to Levenmouth, accessible at Levenmouth Railway Link | ScotRail

[76] The Scotsman (2024), Scottish towns risk being 'cut off' as 1,400 live bus routes axed, accessible at Scottish towns risk being 'cut off' as 1,400 live bus routes axed

[77] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the

transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[78] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 30). Available at:

[79] The Highland Council (2023), Local Transport Strategy: Draft Case for Change, accessible at Local Transport Strategy Case For Change | Local Transport Strategy Case for Change - Full Report

[80] Centre for Cities (2023), Miles Better: Improving Public Transport in the Glasgow City Region, accessible at Miles-better-October-2023.pdf

[81] Centre for Cities (2023), Miles Better: Improving Public Transport in the Glasgow City Region, accessible at Miles-better-October-2023.pdf

[82] Transport Scotland, Young Persons’ (Under 22s) Free Bus Travel, accessible at: Under 22s free bus travel | Transport Scotland

[83] Transport Scotland, 60+ or Disabled, accessible at Eligibility and Conditions for the 60+ or Disabled Traveller

[84] Scotrail, Young Scot National Entitlement Card, accessible at Young Scot National Entitlement Card - 16 to 18 | ScotRail

[85] Scotrail, National Entitlement Card, accessible at National Entitlement Card | Concessionary travel | ScotRail

[86] mygov.scot, Ferry Concessions for National Entitlement Card Holders, accessible at Ferry concessions for National Entitlement Card holders - mygov.scot

[87] Transport Scotland (2025) Free inter-island ferry travel introduced for young people in Orkney, Shetland and the Outer Hebrides, accessible at Free inter-island ferry travel introduced for young people in Orkney, Shetland and the Outer Hebrides | Transport Scotland

[88] Transport Scotland, Information on Other Concessionary Travel and Discounted Schemes, accessible at Information on other concessionary travel and discounted schemes | Young Scot National Entitlement Card discounts | Transport Scotland

[89] Strathclyde Partnership for Transport (2015), Strathclyde Concessionary Travel Scheme: Scheme Guidance & Notes for Operators, accessible at Report for

[90] Edinburgh Trams (2022), Free Tram Travel for Young People under 22, accessible at Free Tram Travel for Young People under 22 | Edinburgh Trams

[91] Edinburgh Trams, Do you offer discounts for seniors?, accessible at Do you offer discounts for seniors? | Edinburgh Trams

[92] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 30). Available at:

[93] Consumer Scotland (2024), Consumers and the National Concessionary Travel Schemes, accessible at cm24-04-ncts-evidence-review-publication.pdf

[94] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 30). Available at:

[95] Consumer Scotland (2024), Consumers and the National Concessionary Travel Schemes, accessible at cm24-04-ncts-evidence-review-publication.pdf

[96] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-surveyyougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[97] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 30). Available at:

[98] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-surveyyougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[99] Bus Users (2024), Why Are We Waiting? Disabled People’s Experiences of Travelling By Bus, accessible at https://bususers.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Mobility-Report-2024.pdf

[100] Office of Road and Rail (2024), Experiences of Passenger Assist, accessible at https://www.orr.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2024-07/2023-2024-passenger-assist-report-mel-research.pdf

[101] BBC (2024), The Island Ferries Making Life Difficult for Disabled People, accessible at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cr7r542dy3xo

[102] Glasgow Times (2021), Bid to Improve Wheelchair Accessibility on Glasgow Subway, accessible at https://www.glasgowtimes.co.uk/news/19175732.bid-improve-wheelchair-accessibility-glasgow-subway/

[103] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-surveyyougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf

[104] Transport Scotland (2023), Women’s and Girl’s Views and Experiences of Personal Safety When Using Public Transport, available at https://www.transport.gov.scot/publication/womens-and-girls-views-and-experiences-of-personal-safety-when-using-public-transport/

[105] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 30). Available at:

[106] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024 (question 30). Available at:

[107] Transport Scotland (2022), Social and Equality Impact Assessment (SEQIA) – NTS Delivery Plan, accessible at https://www.transport.gov.scot/publication/social-and-equality-impact-assessment-seqia-nts-delivery-plan/

[108] The Poverty Alliance research ( accessible at Poverty-Alliance-Briefing-for-Debate-on-Fair-Fares-Review-March-2024.pdf) has found that safety concerns exist for black and minority ethnic people, as well as disabled people and women and girls on public transport. Meanwhile, an LGBT Youth Scotland research briefing (Transport-debate-230612-WEB.pdf) found that only 48% of people in reported feeling safe when using public transport, a number that has been steadily falling since 2012.

[109] MIT Climate Portal (2022) Are electric vehicles definitely better for the climate than gas-powered cars? (accessible at Are electric vehicles definitely better for the climate than gas-powered cars? | MIT Climate Portal

[110] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the

transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[111] Transport Scotland (2025), Scottish Transport Statistics 2024, accessible at Scottish Transport Statistics 2024 | Transport Scotland

[112] Which? (2024), Which?’s Annual Sustainability Report Series 2024: Electric Vehicles, accessible at Which?’s Annual Sustainability Report Series 2024: Electric Vehicles - Which? Policy and insight

[113] Which?’s Annual Sustainability Report Series 2024: Electric Vehicles - Which? Policy and insight

[114] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the

transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[115] Thinks Insight and Strategy (2024) Exploring consumers’ participation and engagement in the

transition to net zero in Scotland. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/5ljbbkzg/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-qualitative-research-with-consumers-thinks-insight-strategy-final-report-pdf-version.pdf

[116] Consumer Scotland (2024), Consumer Experience of Electric Vehicles in Scotland, available at en24-02-low-carbon-technologies-electric-vehicles-publications-consumer-scotland-insight-report-clean.pdf

[117] Consumer Scotland (2024), Consumer Experience of Electric Vehicles in Scotland, available at en24-02-low-carbon-technologies-electric-vehicles-publications-consumer-scotland-insight-report-clean.pdf

[118] Consumer Scotland (2024), Consumer Experience of Electric Vehicles in Scotland, available at en24-02-low-carbon-technologies-electric-vehicles-publications-consumer-scotland-insight-report-clean.pdf

[119] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Electric Vehicles Experience Survey 2024, available at en24-02-low-carbon-technologies-electric-vehicles-publications-yougov-research-report-pdf-version.pdf

[120] Scottish House Condition Survey: 2021 Key Findings Chapter 01 Key Attributes of the Scottish Housing Stock - tables and figures

[121] Consumer Scotland (2024), Consumer Experience of Electric Vehicles in Scotland, available at en24-02-low-carbon-technologies-electric-vehicles-publications-consumer-scotland-insight-report-clean.pdf

[122] YouGov (2024) Consumer Scotland: Net Zero 2024. Available at: https://consumer.scot/media/g35ij55f/xm24-02-consumers-and-net-zero-net-zero-consumer-surveyyougov-final-report-pdf-version-for-publication.pdf