1. Executive Summary

Tenancy challenges in the private rented sector

The 311,000 households in Scotland’s private rented sector are consumers of housing services.[1] As consumers of housing services, tenants should have access to clear information about the terms of their tenancy, and it should be made easy for them to know how to seek the resolution of any problems that arise during the tenancy. These tenancy challenges could include rent increases, unsatisfactory housing conditions, the threat of eviction, and deposit issues.

The ongoing housing emergency has highlighted the need to strengthen protections, awareness, and access to redress for private tenants – who are more likely to face tenancy challenges than tenants in the social rented sector. Despite the existence of a number of redress pathways, including the First-Tier Tribunal, Rent Service Scotland, and enforcement by local councils, many tenants do not raise issues with their landlords, seek advice, or pursue a formal resolution. The new Housing (Scotland) Bill and the Scottish Government’s Housing Emergency Action Plan contain various measures to improve the supply and quality of private tenancies, but do not address this issue.

Questions we asked

Our scoping study A Fairer Rental Market: Consumer challenges in the private and social rented sectors identified a need to obtain a more nuanced insight into tenants’ experiences and perceptions of existing redress pathways, to better understand what is deterring them from pursuing resolutions and how this can be improved.[2] We commissioned Thinks Insight & Strategy to explore these issues through interviews with private tenants who have experienced tenancy issues, focus groups with advisers who support tenants, and interviews with expert stakeholders including researchers. The fieldwork, which was undertaken in January and February 2025, explored:

- Levels of tenants’ awareness of their rights and redress pathways for any disputes

- The extent to which they are reliant on external advice

- What motivated informed tenants to seek, or not to seek, redress

- How tenants experienced redress pathways and what improvements could be made

Full findings of the research can be accessed in the Thinks Insight & Strategy research report.

Improving the experience of tenants - the role of this report

This report builds on the findings of the qualitative research we commissioned in two ways. First, it places the findings in the context of broader evidence on the challenges facing private tenants in Scotland. Second, it draws on this evidence to provide a range of detailed recommendations designed to improve private tenants’ experience of resolving issues they face. These relate to information and signposting, and accessibility of a range of advice services.

We hope this report provides useful evidence for policymakers, advice services, those operating redress systems, and other stakeholders who seek to improve the renting experience of private tenants across Scotland.

As the statutory advocate for consumers in Scotland, Consumer Scotland will continue to actively engage with the Scottish Government to inform ongoing policy discussions and to implement the recommendations in this report.

Key Findings from our Qualitative Study

There is a lack of clarity around rights, advice, and redress options. While tenants can achieve a resolution, this often require ongoing advice and support.

Uncertainty and low expectations of tenancy rights prevent action

First-time renters especially start with limited knowledge | Power dynamics can act as a deterrent | There are ‘grey areas’ around who is responsible for addressing issues and when

Formal advice is often needed as a catalyst for pursuing a resolution

Tenants can feel uncomfortable seeking formal advice relating to tenancy issues | There is limited awareness of which advice services can help | Formal advice is generally experienced as empowering when accessed

Existing pathways can be uninviting to tenants

Experiences of redress pathways vary | Tenants are faced with navigating complex processes, long delays, concerns around retaliation | While the outcome is often satisfactory, the effort and risk may not seem worth it

Accessing formal redress requires ongoing support

Tenants often fear that pursuing redress might result in landlord retaliation | Access to legal aid is a determining factor | Ongoing support from advice agencies is crucial throughout

Tenants generally do not seek advice unless there is an element of urgency

Redress journeys vary, depending on individual factors such as awareness, personalities, personal circumstances, and experiences | Action is often kickstarted by urgent issues, health impacts, or sustained landlord inaction

Key Recommendations

Based on these findings, we have made a number of recommendations to the Scottish Government. These require a cohesive approach that includes working with stakeholders from across the housing, advice, and redress sectors, and user-testing with tenants. Consumer Scotland is willing to play a facilitating role where we consider this appropriate.

Chapter 5 sets out our recommendations in full, including specific recommendations to improve different redress pathways.

Recommendation 1: Information

The Government should work with stakeholders to ensure that tenants and landlords have clarity on existing and new rights and obligations following passage of the Housing Bill

- Review the Model Private Tenancy Agreement and Guidance to include practical information and references to issues like mould and damp

- Improve signposting to information and advice

- Ensure that tenants and landlords are made aware of the existing and new rights and obligations

Recommendation 2: Advice

The Scottish Government should work with partners to improve access to free and early advice to help tenants resolve issues they are facing

- Explore improved signposting, referrals to specialist services, and developing guidance to help streamline the tenant journey

- Consider including housing advice agencies in any future phases of the Fairer Funding pilot

Recommendation 3: Ongoing Support

The Scottish Government should explore how it can provide free end-to-end support for tenants who require this to help them engage with formal redress processes

- Increasing access to in-house Tribunal support

- Consider how to increase access to in-court advisers in context of legal aid reform

Recommendation 4: Improved Processes in Redress Pathways

The Scottish Government should take a number of actions to ensure that tenants are able to access redress pathways that are timely, transparent, and easy to navigate, whilst being reassured they are protected during the process

- Improve timeframes for Tribunal hearings and clarity and user-friendliness of Tribunal communications, e.g. through an interactive website

- Increase awareness of Rent Service Scotland and its decision-making framework

- Work towards more consistency in local authority practices to help ensure equitable access and service levels for private tenants across Scotland

2. Background

About us

Our purpose is to improve outcomes for current and future consumers, and our strategic objectives are:

- To enhance understanding and awareness of consumer issues by strengthening the evidence base

- To serve the needs and aspirations of current and future consumers by inspiring and influencing the public, private and third sectors

- To enable the active participation of consumers in a fairer economy by improving access to information and support

Consumer Scotland uses data, research and analysis to inform our work on the key issues facing consumers in Scotland. In conjunction with that evidence base we seek a consumer perspective through the application of the consumer principles of access, choice, safety, information, fairness, representation and redress.

We have a particular focus on three consumer challenges: affordability, climate change mitigation and adaptation, and consumers in vulnerable circumstances.

Consumer principles

The Consumer Principles are a set of principles developed by consumer organisations in the UK and overseas.

Consumer Scotland uses the Consumer Principles as a framework through which to analyse the evidence on markets and related issues from a consumer perspective.

In the context of consumers as tenants, the principles can be applied as follows:

- Access: Do consumers have the opportunity to access affordable tenancies that meet their needs?

- Choice: Do consumers have enough choice about what market to enter and what property they rent?

- Safety: Do tenants receive the support they need to help ensure their homes are well-maintained and free of damp, mould, and other hazards?

- Information: Are consumers made aware of key characteristics and their rights before they sign a tenancy or when they suffer detriment?

- Fairness: Are there examples of good policy or practice in one sector that could be applied to improve the renting experience for tenants in another sector?

- Representation: Do consumers have a voice when it comes to shaping their housing conditions or rent levels?

- Redress: Are consumers able to access advice and exercise their rights when the property doesn’t meet their needs, when there is an undue increase in rent or other issue that requires resolution?

Consumer Scotland: A Fairer Rental Market

Consumer Scotland commissioned this research as part of a programme of work. We aim to gather evidence and identify policy solutions aimed at reducing harm to consumers who are tenants, increasing consumer confidence, and advancing fairness across rental sectors. We are using our research and advocacy functions to seek improved outcomes for tenants. Our first A Fairer Rented Market publication was our scoping study Consumer challenges in the private and social rented sectors, in November 2024.[3] At the time of publication of this research, we are also carrying out a detailed, quantitative study into experiences of social housing tenants, which we aim to publish in winter 2025/26.

Through this qualitative research we have gathered evidence on private tenants’ experiences and perceptions of advice and resolution pathways when navigating tenancy issues. This has helped us to identify how and where Consumer Scotland can best add value and advocate for improvements. We consider that this research may be of similar value to policymakers and other stakeholders who seek to improve outcomes for private tenants.

The Private Rented sector in Scotland

Consumers should be able to access goods and services that are affordable, safe, and secure. If a good or service is of poor quality or does not meet standards, consumer rights are there to protect them and to facilitate redress. Tenants need the same in relation to the homes they live in, and they must be able to hold their landlords to account when they experience problems, such as repair issues.

Tenant safety is impacted by the condition of their home, and by the landlord’s willingness or ability to maintain their property. While private landlords can be individuals or businesses, the vast majority of landlords in Scotland own only one property.[4] A recent survey of over a thousand Scottish Landlords suggests that the vast majority (90%) are either private individuals or a couple/family.[5] This may result in a risk that many landlords do not have the necessary awareness of the obligations they have towards their tenants. It is also worth noting that social homes in Scotland are subject to stricter standards than private homes, which we discussed in our scoping study.

Affordability and security of tenancies are impacted by wider circumstances in the rental market, such as the lack of affordable housing supply. After Scotland was declared to be in a housing emergency in May 2024, the Scottish Government convened a Housing Investment Taskforce to identify ways to improve this.[6] Its recommendations were published in March 2025.[7] This was followed by the publication of a Housing Emergency Action Plan in September 2025, which contains measures aimed at ending incidences of children living in unsuitable accommodation, supporting the housing needs of vulnerable groups, and supporting growth and investment in the housing sector.[8]

While our study does not seek to address these wider rental market issues, it is important to note the impact of supply pressures in the housing market on tenants’ ability to afford their rent or their ability to leave and secure a new tenancy. We have also previously noted that these pressures may mean that some consumers who would have normally rented from a social landlord may now need to rent privately.[9]

At the time of publication of this paper, the Housing (Scotland) Bill has just been passed by the Scottish Parliament. While this legislation is focussed on tackling excessive rent increases in the private rented sector, it also contains a commitment to implement Awaab’s Law[10] [11] in Scotland for both social and private tenancies, to help ensure that investigations and repairs are carried out within strict timeframes. During Stage 2 proceedings on the Housing Bill, the Scottish Government committed to exploring policy solutions on a number of issues, including repairs and housing standards, homelessness prevention and evictions.[12]

Research suggests that tenants in the private rented sector experience a number of issues where they could potentially seek redress. For example, the 2022 CaCHE report Living in Scotland’s private rented sector found that 4 out of 10 private tenants experienced a dispute with their landlord or letting agent, mostly around repairs and property condition.[13] The Scottish House Condition Survey 2022 also found that consumers renting in the private rented sector are the most likely to be in a property that is in a state of any disrepair to critical elements, and urgent disrepair to one or more critical element. [14]

In the Draft Rented Sector Strategy published in December 2021, the Scottish Government committed to establishing a private rented sector housing regulator by 2025, to improve housing standards and the quality of service private tenants receive.[15] It is unclear whether this is still current Scottish Government policy. The social rented sector meanwhile is regulated by the Social Housing Regulator, and social tenants are able to take complaints to the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman.

If their issue is not resolved, private tenants can seek a resolution through specific pathways including the Housing and Property Chamber of the First-Tier Tribunal for Scotland (“the Tribunal”), Rent Service Scotland, and local authority private sector housing teams. Yet in practice, private tenants are experiencing issues when it comes to understanding and exercising these rights.

Evidence suggests that many tenants who may have grounds for complaints do not access these pathways. SafeDeposits Scotland’s Voice of the Tenant Survey 2024 found that only 9% of those who had experienced an issue that had not been addressed by their landlord escalated complaints to their local authority, and just 4% approached the Tribunal. [16] The survey also found that 45% of tenants didn't know where to go if their landlord or agent failed to resolve a housing problem.

RentBetter research in 2024, carried out by Indigo House on behalf of the Nationwide Foundation, found that while 63% of tenants indicated that they would feel confident seeking a resolution from their landlord or letting agent, 28% were neutral or unsure, and 10% would not be confident.[17] It also found that only 3.6% of respondents had sought independent help or advice to assist in resolving their dispute. However, when they did, the advice received was found to be helpful. The research found only 1 in 3 tenants were aware they could apply to the Tribunal.

The RentBetter research series also conducted in-depth interviews with 10 tenants who had experience with the Tribunal.[18] All of these 10 participants felt that the process was lengthy, formal and inaccessible. While this sample is small, it provided an indication of shared experiences of private tenants with the Tribunal process. A Shelter Scotland review in 2020 established that there remained an evidence gap regarding the actual qualitative experiences of tenants who choose or choose not to raise and pursue disputes, and the experiences and value of different systems and forms of redress.[19]

Current use of redress pathways

Private tenants experiencing unresolved disputes with their landlord can generally apply to the Tribunal. The Tribunals (Scotland) Act 2014 created a new, simplified statutory framework for tribunals in Scotland, creating the First-tier Tribunal for Scotland, and the Upper Tribunal for Scotland to handle appeals.[20] The Housing and Property Chamber is part of the First-tier Tribunal. The Tribunal forms part of the Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service, and the Scottish Civil Justice Council can give advice and make recommendations to help improve the way it operates.[21]

While both tenants and landlord may use legal or lay representation, most of them do not. Tribunal data shows that landlords are far more likely to have representation than tenants are, e.g. 63% of applicants (landlords) in 2022/23 were represented at any stage in eviction cases, but only 7% of tenants.[22] An August 2025 submission by the University of Glasgow School of Law to the Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee Inquiry into Civil Legal Aid, indicated that there is a high level of unmet legal need in housing and homelessness law.[23] It also noted that most tenants who have representation are being assisted by lay representatives. This may indicate a need for increased awareness or access to legal aid.

We note that the Scottish Legal Aid Board provides funding for legal representation for eligible tenants for a wide variety of Tribunal cases, but there is a growing shortage of legal aid solicitors, as well as a lack of data to help understand the extent to which there is unmet need across a wide number of communities in Scotland. This may disproportionately impact on tenants who are in vulnerable circumstances, living with health needs, or in deprived communities. In addition, the Independent Strategic Review of Legal Aid in Scotland commissioned by the Scottish Government found that many consumers did not know the criteria for qualifying for legal aid, what it could be used for or which lawyers provided it.[24] Many had the perception that legal aid was not for them. Given these concerns around access to legal aid, the Scottish Government has reformed legal aid fees, is simplifying the legal aid system, and is preparing to introduce proposals to improve the provision of legal assistance through primary legislation in 2026. Consumer Scotland provided written evidence to the recent Scottish Parliamentary Civil Legal Aid Inquiry and will continue to engage on this issue.[25]

In 2023/24 the Tribunal received record numbers of eviction, repairs, and property factor cases. It should be noted that the removal of some of the temporary COVID-related restrictions on evictions during that year will have impacted on some figures. The largest percentage increases were applications regarding Repairing Standards (+38%), Evictions (+19%), and Property factor applications (19% on top of a 19% increase the year prior), overtaking tenancy deposit applications to become the third largest category.[26]

The Tribunal does not currently evaluate the experiences of its users, and we have previously highlighted that publication of more granular data would be beneficial to establish how tenants are interacting with the system and where policy or process changes may be needed to achieve improved outcomes for tenants.

If a tenant with a Private Residential Tenancy considers a proposed rent increase too high, they can refer this to Rent Service Scotland. Generation Rent found that in the year after the introduction of a 12% rent cap in April 2024, Rent Service Scotland received 899 applications from tenants who deemed their rent increase to be too high.[27] From 1 April to 31 December 2024, Rent Service Scotland received 1,250 rent adjudication applications.[28]

Private tenants can also ask their local authority to carry out a property inspection. We are not aware of any data sources recording statistics or trends in relation to tenants seeking help from local authority assistance and enforcement teams, and consider that it would be beneficial to collate such data to help establish levels of demand and current usage for such services.

Aside from the three main pathways our research has focused on, there are a number of other resolution mechanisms that are open to some private tenants. For certain disputes there is the option of claiming under Simple Procedure at the Sheriff Court. This may be an option for tenants to seek an order to make a landlord carry out repairs if the Tribunal dismissed their case, or to recover sums owed, up to a maximum of £5,000, from their landlord.[29] Other options include redress schemes, which landlords or letting agents are not obliged to join, adjudication services associated with deposit schemes which can determine deposit issues, and mediation services.

Housing-specific research by the University of Strathclyde Mediation Clinic has suggested that the inability of the Tribunal to refer cases to a specific mediation service provider formed a “major barrier”, and that “more needs to be done to highlight the benefits of mediation to the sector”.[30] This suggests that more work is required to increase understanding of the role of mediation and to promote smoother pathways if it is to become a more mainstream dispute resolution option for private tenants across Scotland.

3. Research Aim and Methodology

Research Aims

Consumer Scotland commissioned this research to better understand how well the current advice and redress system is working for private tenants in Scotland who have a landlord dispute, and to explore what better would look like. The research was carried out by Thinks Insight & Strategy and will be referred to as “our research” throughout this report.

Research Methodology

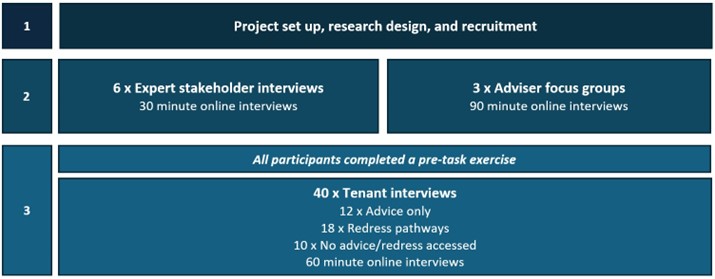

The research took a 3-stage qualitative approach and included engagement with private tenants, advisers, and expert stakeholders.

Figure 1: We conducted qualitative research with private tenants, advisers, and expert stakeholders.

Expert Stakeholder Interviews: To inform the research scope, Thinks Insight & Strategy conducted six 30-minute online interviews with expert stakeholders - defined as individuals with knowledge of private tenants' issues and experiences of seeking advice or redress. Participants included advisers and solicitors from local Citizens Advice Bureaux (CAB), Living Rent, the Legal Services Agency, SafeDeposits Scotland Charitable Trust, and Indigo House Group. These interviews provided context for later research stages.

Adviser Focus Groups: To draw on the expertise of frontline advisers, Thinks Insight & Strategy initially ran two 90-minute online focus groups with eight advisers and solicitors supporting tenants. A third follow-up group was held towards the end of the research to refine themes and gather further insight. Participants were recruited via desk research, outreach, and referrals from Consumer Scotland. They included staff from law centres, Advice Direct Scotland, the Legal Services Agency, Age Scotland, and CABs. Focus group discussions included tenant issues, barriers to seeking advice and redress, and areas for improvement in current pathways.

Tenant Interviews: The core research stage involved 40 in-depth, 60-minute online interviews with private tenants across Scotland aged 18 and over who had experienced unresolved issues with their tenancy. This did not include student tenants, as work has shown their circumstances to be particularly distinctive. The interviews were held between January and February 2025 and explored tenants’ housing issues and use (or non-use) of advice or redress services. Participants were generally recruited through a recruitment body, as well as an individual recruiter to engage underserved demographics. A 30 to 45-minute digital/paper activity helped participants map their housing issue journey, aiding recall and interview depth.

Prior to the interview, tenants were asked to complete a pre-task exercise, to help them recall and articulate their experiences. Thinks interviewed:

- 12 Tenants who had sought advice from official advice agencies, such as advice centres, but did not access redress pathways

- 18 Tenants who had sought advice (either initially or ongoing) and who pursued redress e.g. through the Tribunal or local authority enforcement teams

- 10 Tenants who experienced similar housing issues that impacted upon them and that would make them eligible for redress, but who did not seek out advice or access redress pathways

The issues discussed included repairs, poor conditions, deposits, rent increases, and evictions. The interview topics were:

- Advice/redress journey

- Barriers and challenges

- Understanding of rights as private tenants

- Reasons for (not) accessing redress

- How redress pathways function and could be improved.

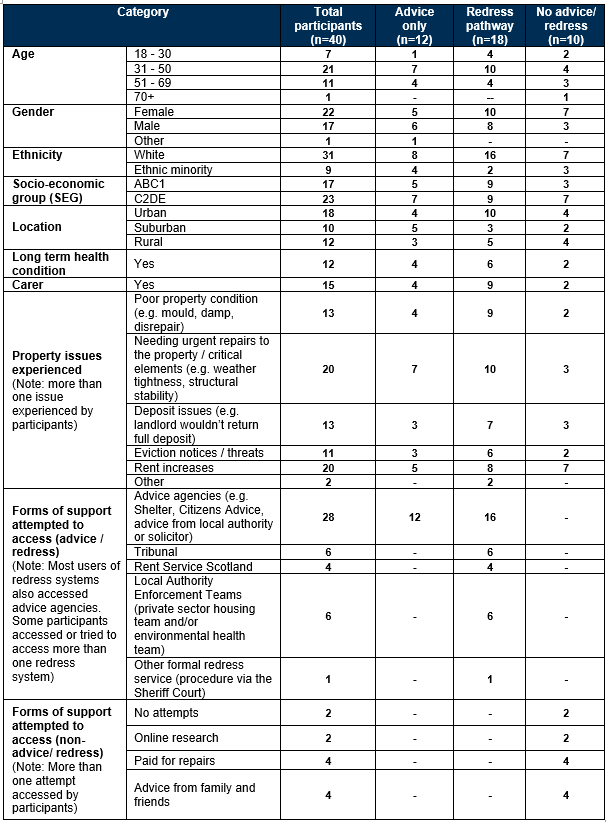

A breakdown of our sample follows. Full details can be found in the Thinks Insight & Strategy report.

Figure 2: Our research panel included a wide variety of tenant participants

16 out of the 28 tenants who had sought formal advice went on to seek redress

4. Findings

Our commissioned research resulted in five key findings which are discussed below:

- Uncertainty and low expectations around tenancy rights prevent tenants from taking action

- Tenants generally do not seek advice unless there is an element of urgency

- Formal advice is often needed as a catalyst for pursuing a resolution

- Accessing formal redress requires ongoing support

- Existing pathways each have their own specific challenges that can make them uninviting to tenants

Uncertainty and low expectations around tenancy rights prevent tenants from taking action

Existing evidence suggests that private tenants experience barriers which prevent them from reporting issues they face. Survey research finds that the majority of tenants report that they would feel confident seeking resolutions from their landlord/letting agent (63%).[31] However, only a minority (9%) seek further resolution if problems are not initially addressed. [32] We wanted to explore why this is the case.

Uncertainty and low expectations around tenancy rights feed into the perception that tenants have few rights, that the law favours landlords in relation to property issues, and that there is little point in reporting issues to the landlord.

Limited awareness of rights

Tenant participants in our research were often unsure of their tenancy rights and relatedly, about what they can ask for and challenge.

Awareness was lowest amongst those who were renting privately for the first time. This was particularly the case for older participants, who had previously lived in their own homes or who had moved into private renting from the social rented sector. It was also more of an issue for younger participants, who previously lived in their family home or with others. In this context we note findings from Independent Age which found that only 30% of older tenants (in either sector) felt fully informed about their housing rights, with 21% saying they did not know anything about their housing rights and 36% being unsure.[33]

This is consistent with the RentBetter findings that households with older tenants (43%) were the most likely to have had problems with their tenancy in the previous five years - mostly repair issues and issues with property condition.[34] The lack of awareness of tenant rights amongst older people, together with their likelihood of experiencing issues, puts them at an increased risk of detriment.

Tenant participants were also unsure which temporary protections against rent increases and evictions, introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic, were still in place. Such uncertainty can be expected to continue, as regulations continue to develop. Our fieldwork concluded in February 2025. The Cost of Living (Tenant Protection) (Scotland) Act 2022, which included the rent cap and temporary modifications to rent adjudication, expired at the end of March 2025. In addition, the Scottish Parliament passed a new Housing Bill in September 2025, which allows local authorities to propose Rent Control Zones with rent increase caps of CPI+1% (maximum 6%). These measures are anticipated to take effect in 2027. Once this happens, tenants will have to monitor whether their (prospective) home is subject to rent controls. All of this means it will take a while before a consistent framework will be in place, clearly defining the landlord’s right to increase the rent and the tenant’s rights to challenge this.

Power dynamics in the landlord-tenant relationship

Citizens Advice Scotland presented mixed method data on the repair issues that CAB clients experience in their 2023 report, In a Fix[35]. They note concerns, especially from private tenants, about the reported “threat of eviction or illegal eviction” when reporting repair issues. Given the fear of losing their tenancy, the problem is often left and may deteriorate further. RentBetter research found that tenants at the lower end of the market expressed a sense that if the relationship with their landlord failed or trust was compromised, their security of tenure could be at risk.[36] Tenants did not feel confident in their rights and often feared exercising them due to concerns about potential repercussions, such as rent increases or losing their home, in a housing system with very limited options for people on low incomes. We wanted to know more about why tenants did not report issues to their landlord and what it would take to change this.

“I wouldn’t say I [know much] about what rights I have as a tenant. I’ve always just assumed, at the end of the day, it’s [the landlord’s] house, and I’m renting off them.”

- Rent increase, No advice or redress

Interviews with tenant participants indicated that uncertainty around their rights as tenants is often rooted in a belief that they do not have many rights, and that their landlord is unlikely to resolve the issue or take their complaint seriously. As noted later in this report, when tenants experience a problem, finding out who is responsible is often not clear cut. Since many disputes fall into ‘grey areas’, this contributes to the lack of understanding on the part of both tenants and landlords of their rights. This is likely to be a contributing factor to low rates of reporting issues.

Participants suggested that negative perceptions can be reinforced by media reports about untreated damp and mould cases, as well as conversations with friends and family who rent privately. As such, some tenants are of the view that bad experiences are to be expected in the private sector.

Existing research showed that some tenants do not raise issues due to fears that they may lose their tenancy through eviction.[37] Even when tenants consider their relationship with their landlord to be good, they may still feel anxious about reporting disrepair.[38] Participants in our research also voiced concerns that reporting issues might result in rent increases, or in part of their deposit being withheld when they do leave their tenancy. This means that fears of retaliation go beyond the possibility of being evicted, and include concerns about financial consequences, both during and after the tenancy.

The research we commissioned shows that these fears are particularly pronounced amongst tenants in vulnerable circumstances, who may have fewer options and less flexibility to move, and as such feel more dependent on their current tenancy and landlord. This includes tenants who are on a low income or in receipt of benefits, tenants with long term health conditions, and single person households or families with children.

Many tenant participants were unaware of the extent of their rights and some expressed mistrust and frustration with letting agents in particular. However, first time renters and those renting directly from a landlord, particularly under private rental contracts, held more optimistic views of landlord relationships.

Tenant participants also felt that the relationship was more personal than formal and as such, they expected landlords would feel a ‘duty of care’ towards tenants based on a sense of personal responsibility rather than just legal obligations. Tenant participants who reported issues expressed shock when this expectation was not reciprocated and where landlords responded to reports of issues in a formal, businesslike, or even combative tone.

Ambiguity and ‘grey areas’ around rights and responsibilities

We wanted to understand what tenants commonly know, and where it might be most useful to focus work to ensure that tenants and landlords have clarity on their rights and obligations. We find that tenants generally understand that landlords are required to return deposits and give advance notice to terminate the lease. Tenants also understand that they are required to pay rent, and to keep their home in good condition.

However, there are a number of issues where tenants considered rights and responsibilities more difficult to establish, especially regarding disrepair and rent increases. We will refer to these as ‘grey areas’. Figure 3 describes a number of grey areas the research identified, illustrated by examples of experiences participants have had.

Figure 3: There are a number of “grey areas” in relation to rights and responsibilities

There is often a lack of clarity around when landlords have maintenance responsibilities, or what is meant by legal concepts and terminology

| Grey Area | Participant experience |

|---|---|

| When repair and maintenance issues gradually deteriorate it can be unclear at what point a landlord needs to act | A tenant initially attempts to resolve damp and mould problems by repeatedly wiping condensation off poorly insulated windows, but it persists |

| When a landlord attempts to resolve a repair or maintenance issue, the tenant may not know where they stand | A landlord repeatedly sends their unqualified father to fix leaking pipes, resulting in poor quality repairs - until the tenant insists on professional repair |

|

When a landlord increases the rent it is unclear whether it can be considered 'affordable' and when the tenant can complain |

A tenant who is on a low income is unable to afford any increases, but is unsure if the increase is deemed unaffordable and if they have the right to challenge it |

| When there are imperfections to the property, it can be unclear what is damage done by the tenant and what is wear and tear | A tenant is experiencing issues with their showerhead and it is unclear whether this is caused by their actions or natural wear and tear |

| When tenants sign their lease agreement, many do not understand the language describing who is responsible for what and they hope the landlord will fulfil a perceived duty of care | A tenant receives a 57-page lease agreement containing a lot of jargon, which, despite their education, they find difficult to understand and they are not aware of the legally binding elements within it |

| When a tenant rents through a letting agent, they often experience delays and it is unclear whether the agent or landlord is responsible for not getting back to them | A tenant experiences black mould in their bathroom and repeatedly contacts the letting agent, who claims to be unable to reach the landlord |

These ‘grey areas’ highlight that solutions will not only lie in improving tenants’ and landlords’ awareness of their rights, but also in improving clarity around how and when these rights apply in a more practical sense.

SafeDeposits Scotland’s Voice of the Landlord Survey 2024 found that 26% of Scottish landlords experienced the challenge of tenants not reporting repair and maintenance issues in the last 12 months.[39] Delayed reporting may lead to maintenance problems worsening over time, creating issues for both landlords and tenants. Greater shared understanding and clarity on roles and responsibilities could help improve confidence in communicating issues earlier. In our engagement around the Housing Bill we have argued that, while improved information sharing between authorities is welcome, there is a need to provide clear tenancy documents, as well as improved access to information for both tenants and landlords.

The Voice of the Landlord Survey 2024 also reported that landlords can find regulatory changes in Scotland difficult to navigate. Just 51% of Scottish landlords said that they can keep up with new laws affecting their rental properties, and 39% did not feel changes in the law are clearly communicated to landlords. This suggests that activities to raise awareness of regulatory requirements should extend to landlords.

Tenants generally do not seek advice unless there is an element of urgency

As discussed in Chapter 1, existing evidence shows that tenants mostly experience issues with property disrepair and poor conditions (including damp and mould), eviction notices, rent increases, and deposits. We wanted to find out to what extent the type of issue might shape a tenant’s decision to seek formal advice or redress.

The research found that advice and redress journeys vary depending on the issue and the tenant, but generally, tenants are more likely to manage repair and maintenance issues themselves and only seek formal advice when issues are exacerbated (for example, where they experience health impacts). Tenants are more comfortable seeking advice regarding deposit issues, likely because these tend to occur once the tenant has already moved out and there is no risk of losing their home. However, being faced with the possibility of losing their home also drives tenants to seek advice, as our research found that eviction threats and high rent increases elicit the most immediate search for support.

“I went into fight or flight mode. When you’re doing it for your children and as a mother, you do whatever you can…

I mean all of this stuff comes down to the housing shortage…. If there was plenty of rents available, it would have been easy-peasy. I started to look online to bid for places but you couldn’t even get viewings nowadays, they just fill up.

I was in a complete state of extreme stress, and I mean extreme.”

- Rent increase, No advice or redress

Whether a tenant seeks advice and/or redress also depends on a range of individual factors relating to the tenant’s:

- Awareness of their rights, advice, and or redress options

- Individual circumstances (for example, whether they have time or energy to seek support whilst managing a long-term health condition)

- Personality (many participants saw themselves as ‘not the kind of person’ to be perceived as confrontational)

- Prior experiences with formal advice

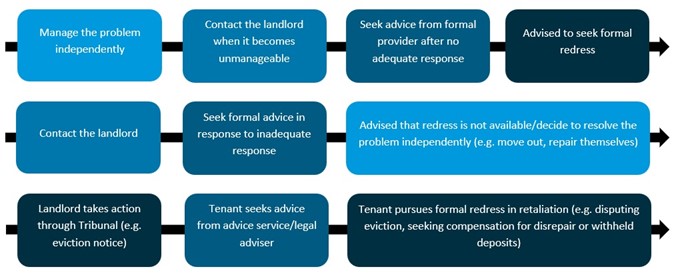

Figure 4: Three examples demonstrating differing advice and/or redress journeys of participants.

What a tenant’s journey looks like depends on a variety of factors, but formal advice is often a catalyst to seeking resolution

Repair and maintenance

Tenants experiencing poor property conditions are initially inclined to self-manage, e.g. by wiping away mould or replacing items. Our research identified damp and mould issues as grey areas, with tenants unsure if and when they should contact their landlord, and noted that tenants often fear landlord retaliation (e.g. through a rent increase to recoup repair costs). Participants indicated that both of these factors play a role in their decision to self-manage poor property conditions rather than asking their landlord to address the issue. In keeping with our finding that first time private renters are especially unaware of their rights, those with more experience are inclined to contact their landlord at an earlier stage.

Participants reported that when they contacted their landlord, they were initially asked to self-manage or they were offered lower-value repairs. Measures taken by participants include buying and using dehumidifiers, repairing or replacing appliances, repainting the property, and fixing holes in walls and ceilings. Self-management often comes with significant costs, especially for tenants on low incomes, without necessarily resolving the issue.

Participants described a range of triggers that prompted them to seek advice or redress when they faced poor property conditions. These included:

- An urgent and sudden issue which is not quickly fully resolved, e.g. a broken boiler

- Health impacts e.g. a child developing a persistent cough from mould

- A sustained period of inaction from the landlord or letting agent

- The landlord refusing to take action

Participants who had not taken any action cited the wider barriers of low awareness, power imbalance, and ambiguity/grey areas in relation to rights and responsibilities.

Eviction notices and threats

When a tenant in a Private Residential Tenancy is served with a valid notice to leave and does not comply within the given timeframe, the landlord can apply to the Tribunal to be granted an eviction order. The Private Housing (Tenancies) (Scotland) Act 2016 provides a number of grounds on which this can be based (e.g. 3 months of consecutive rent arrears, or an intention to sell the property).[40] Eviction applications were previously often paired with civil proceedings seeking a payment order for three consecutive months of rent arrears. However, fewer eviction applications are now made on the ground of rent arrears, and more on the landlord’s stated intention to sell the property. In 2022/23, the Tribunal noted a decrease in civil actions with 2252 eviction applications and 1,250 civil proceedings. [41] The number of these claims being brought together further decreased in 2023/24, with 2687 eviction applications and 1,199 civil proceedings being lodged.[42]

Our research found that when tenants are faced with the threat of losing their home, they are prompted to immediately seek formal, or informal, advice. However, there were some tenants who had decided not to fight their eviction. Both tenant and adviser participants cited a range of interconnected barriers to fighting evictions, including:

- Limited awareness of rights and processes regarding evictions, e.g. without support some tenants would not know that a formal eviction notice is required, that the notice they received was invalid, or how to challenge this

- High personal stakes: to minimise the risk of homelessness, tenants start looking for a new property rather than challenging an eviction and losing

- Fears of impact on their future ability to secure a tenancy: e.g. getting a mark against their name, or getting a poor reference

- Perceptions of the Tribunal process, e.g. that it is complicated, burdensome, and potentially expensive. We discuss this later in the report

- A sense of futility, e.g. that even if they win, the relationship with the landlord would be damaged beyond repair.

“Since the grounds became discretionary we’ve always said stay in your tenancy and fight it out. It’s still your home and you have rights….

I do still feel that 90% of evictions happen before the Tribunal because people move out because they’re stressed and don’t know that they can stay. In legal terms no fault evictions have gone, but by the backdoor they’ve stayed.”

- Adviser

Rent increases

Our research found low awareness amongst tenants of what rent increases were allowable, including low awareness of the 12% rent cap that was in place while the interviews were conducted from January to February 2025. In line with the findings around the power imbalance in the landlord-tenant relationship, many tenant participants assume it is the landlord’s personal prerogative to set their desired rent. Participants also find it difficult to keep up with the numerous temporary policy changes over the last few years.

“It went up by £100 [per month], which had me really watching my expenditure on my weekly shopping and how much of electricity and stuff I’m using. If I’d be going out, just socialising, I’d say is it worth it? I’ll stay in and you can forget takeaway on a Saturday night.”

- Rent increase, No advice or redress

Many tenant participants had their own ideas of what increase is reasonable, and some expressed a strong sense of injustice. While those who consider themselves ‘low maintenance’ tenants (who take good care of the property, pay rent consistently and make few complaints) said they would seek advice or redress, many tenants are not aware that they have the option to dispute a rent increase if it is not reasonable. As such, many participants are likely to resign themselves to the increase, even if this has a significant impact on their finances. If the increase is completely unaffordable, tenants often try to move out. Many participants perceive a high rent increase as an indirect eviction notice, intended to push them out of the property. Being unable to afford the rent and trying to find a new private tenancy can cause extreme stress.

“I thought it was a little kind of unwritten mutual agreement that I don’t pester you too much for the year, and my rent doesn’t go up… like with insurance, if you claim, your premium goes up.”

- Rent increase, No advice or redress

Deposit returns

Private landlords are allowed to charge tenants a deposit of a maximum of two months’ rent, which they must lodge with one of Scotland’s three tenancy deposit schemes within 30 working days of the beginning of the tenancy: SafeDeposits Scotland, MyDeposits Scotland, or Letting Protection Service Scotland.[43]

The research found that tenants often expect landlords to try and withhold some of their deposit at the end of the tenancy. Many emphasised taking photographs of every part of the property when entering and leaving a tenancy, gathering evidence to dispute later potential deductions.

There appears to be more awareness around the option to dispute deposit returns, likely because tenants are informed of this option by their deposit scheme when they are notified of the suggested deposit return. Tenants may dispute claims that are made on protected deposits, but there is little awareness that an unprotected deposit can be claimed at the Tribunal.

Deposit issues present a particular challenge for tenants on low incomes. While they face the most detriment from losing some of their deposit, they are also most likely to urgently require the bulk of the deposit back as quickly as possible – especially if they need to put down a deposit for their next home.

Combined issues

Many tenants see the relationship with the landlord as informal, try their best to be a good tenant, and are inclined to self-manage poor property conditions. Some participants expressed a real sense of injustice where these efforts are met with significant increases to their rent, eviction notices or the withholding of deposits. These can trigger a decision to seek formal advice and or redress in order to seek a resolution to the issues they have been facing.

“Tenants present with often compound problems. Landlords seeking possession to sell the properties, putting an end to uneconomic old-style tenancies, then tenants will come to [advice agencies] with other problems, all of which might have different pathways to resolve them.

There’s a large group of people who just live in poor conditions and need to be encouraged to seek repair standards orders.”

- Adviser

Formal advice is often needed as a catalyst for pursuing a resolution

Existing evidence suggests that 45% of tenants do not know where to turn if their landlord or letting agent fails to resolve a housing problem.[44] However, the proportion of tenants who seeking independent help or advice about a dispute is low compared with the proportion experiencing disputes.[45] We wanted to explore why tenants experiencing issues often do not seek formal advice or support.

Our research found that tenants who are aware of advice bodies are often not aware that these might deal with the issue they are facing. When peers or websites signpost them, they generally find it empowering and often gain the confidence to raise and/or resolve the issue directly with the landlord or letting agent. However, capacity issues can make it challenging for advice bodies to offer appointments immediately.

Barriers to seeking formal advice

3.37 Our research found that tenants often begin with limited awareness of how advice agencies might be able to help them regarding the issue they are facing. This is likely driven by:

- Limited awareness of their rights in the situation

- Limited awareness of the remit of advice bodies regarding their housing issue (e.g. homelessness charities)

- The perception that this is a personal problem rather than a housing rights issue

- The perception that their issue is ‘not serious enough’ until it reaches a crisis point

“I’ve not heard a great deal, I have to say. I’m not really aware of anyone that I can contact about having, you know, issues with the house other than the estate agent.”

- No advice or redress

“When I think of Shelter, what I think of is like a homeless charity, helping out just people that are homeless. I don’t think it’s advertised that it’s there to help people who are in homes. Citizens Advice, again, you kind of think, ‘oh, that’s a worst case scenario’. It needs to be really bad to go to Citizens Advice.”

- Disrepair, rent increase and eviction, Advice only

Instead, many tenants seek informal advice from friends and family when they first experience an issue. This can provide emotional and practical support, and valuable information around rights and advice services, without being perceived as an ‘escalation’.

Participants also associate online searches, the Scottish Government, Shelter, and Citizens Advice websites as being helpful without escalation.

Amongst tenants who are aware that they can seek formal advice, the fear of impacting negatively on the landlord-tenant relationship forms an important deterrent. Participants have expressed fears around feeling uncomfortable in their home once they have escalated to a third party.

Another barrier to seeking formal advice is an awareness that that formal advice services may be operating with limited resources and be overstretched, and the perception that this may lead to long waiting times. Older participants in particular expressed reluctance due to the perception that “[other] people must be in a worse situation” than they are in, along with potential stigma.

Drivers to seeking formal advice

Seeking informal advice can be very useful to help understand one’s rights, and serve as a driver to seek formal advice as a next step. However, it can be difficult to ascertain whether informally obtained information applies to the tenant’s own circumstances. In particular, with personal advice and anecdotal experiences of family and friends, there is a risk that the information given leads to misconceptions about tenants’ rights, advice and redress systems.

Prior positive experiences with advice services are also a driver. Participants who have taken formal advice before, e.g. regarding benefits or debt advice, are more likely to seek formal advice again if they have a housing issue.

Experiences of formal advice

Participants who seek advice generally find it to be empowering and positive. Receiving formal advice around their rights and how to raise issues with their landlord often gives tenants the confidence to directly resolve issues that they did not have before. Examples of such actions are sending a template letter with a letterhead from an advice service, or a letter citing the landlord’s legal obligations or other legal basis for the request.

Participants also note that formal advice services have advised them around what redress pathways are open to them, and have supported them in taking the first steps. For example, some advice services help tenants to seek out and complete the required forms to make an application to the Tribunal.

In some cases, an advice service was able to offer participants continued support throughout a redress pathway, while other participants were referred for specialist support from a law centre.

“I didn’t know anything about it at the start but [local advice agency] helped me with advice on Tribunal and how to apply for it, what the steps would be, what support would be around that… I didn’t even know the Tribunal was an option beforehand.”

- Disrepair, Tribunal

In line with participants’ perceptions, resourcing issues often lead to pressures on capacity of advice services and law centres. This in turn can lead to delays in being able to get a first appointment. As a result, some participants were frustrated and felt that there was little that the advice body could do to help them pursue their desired resolution.

The Scottish Government has long recognised that sustainable, multi-year funding models improve the ability of public and third sector providers to plan and operationalise the delivery of services. Improved access to multi-year funding can assist organisational stability and support more consistent service delivery. We note that in February 2025, the Scottish Government launched the Fairer Funding pilot for charities.[46] Although the pilots include the Scottish Empty Homes Partnership, Homeless Network Scotland, and Housing Options Scotland, funding is mostly focussed on projects supporting health, education, poverty, and culture, and does not currently include support for services that would advise tenants facing issues with their tenancies.

Accessing formal redress requires ongoing support

We wanted to explore what the barriers were to seeking redress once participants were aware of the formal redress pathways. The research found that barriers are complex and difficult to negotiate without ongoing support. Our research found that tenants are more motivated to embark upon, and complete, the process when they have such support.

Some barriers and drivers are shared across redress pathways while others are more unique to particular pathways.

General barriers to seeking redress

3.51 In general, tenant participants had little awareness of the existence and relevance of formal redress pathways including the Tribunal, Rent Service Scotland, and local authority enforcement teams. This was particularly the case for tenants who have not engaged with advice services.

“I wasn’t even aware that there would be an enforcement team in the council for private houses.”

- Disrepair and eviction, Advice only

While we know that advice services play a crucial role in making tenants aware of redress options, not all participants who had sought advice but had been unable to directly resolve their issue with their landlord went on to seek formal redress.

Across all avenues of redress, participants experienced a general perception that tenants have few rights and that the law tends to favour landlords in relation to their property. This sense of imbalance can act as a deterrent. Some tenant participants who had previously rented socially were aware of redress systems within the social rented sector, but assumed that there were no such redress pathway in the private rented sector.

“I would always assume that those things are more geared up for council houses and such.”

- No advice or redress

Our research also found that in the interest of tenants, advisers may on some occasions feel compelled to recommend against following certain redress pathways that are, in principle, available. Factors that could lead them to do this are:

- A low chance of securing the desired outcome

- A high risk of retaliation by the landlord

- Legal aid is required and the inability to recover costs negates any potential reward

- The process is likely to take too long to be helpful, e.g. in case of urgent repairs.

General drivers to seeking redress

The main driver for entering and seeing through a redress pathway is a sense of urgency, when a tenant reaches a crisis point and has very few other options. Participants noted that this might be due to a sudden, significant change like a disrepair issue, or because they felt like they had come to the end of the road seeking an informal resolution with their landlord.

“In the end, the infestation got that bad, I had to move out and had to contact the council [enforcement team], give them all the information and wait for a caseworker to be assigned.”

- Infestation, Local authority enforcement team

Another key driver to start and to see through a redress pathway is having support from an adviser. Participants felt more confident to enter and continue along their redress pathway where information was provided by advisers, although friends or family members were also cited as sources of support.

Participants often feel ‘armed’ with resources and knowledge they receive from advice services, and this contributes to a sense of confidence. Tenant participants with experience of the Tribunal system suggested that assistance received from advice agencies was crucial in navigating a system which can feel daunting and inaccessible.

Existing pathways each have their own specific challenges that can make them uninviting to tenants

While the Tribunal application process was described as complex and lengthy, the six participants in our research who made use of it had largely positive experiences. They described ongoing support and advice as crucial in order to help them navigate and see it through.

In contrast, Rent Service Scotland is perceived by those who accessed it as a user-friendly and quick procedure, but tenants and advisers sometimes reported that they felt the basis on which decisions were made was unclear.

Local Authority enforcement teams are experienced as easy to access and understand, but participants stress the importance of being reassured that they are being protected while they are going through the process.

The Tribunal

A key barrier to applying to the Tribunal is formed by the expectation that engaging with a legal process will be complex, emotionally burdening, and expensive. This is often coupled with the belief that the landlord or letting agent will have more experience, knowledge, and resources at their disposal, to invest in their case. Given this, tenant participants often felt they unable to pursue a resolution at the Tribunal without the support of an adviser.

Tenant participants with experience of the Tribunal found the first steps of making an application challenging, and noted that having the support of an adviser during this stage is incredibly valuable.

Applications to the Tribunal must be made in writing and can be made online. There are 49 different types of applications that can be made by either tenants or landlords, and the onus is on the applicant to determine what type of application form should be used. Each is listed with a link containing guidance on the topic, e.g. “Application for damages for unlawful eviction” or “Application for determination of whether the landlord has failed to comply with the repairing standard”.[47]

The Tribunal website is the main source of information on the system, and both tenants and advisers said they have had difficulties with the navigability of the interface and the complexity of information presented. This experience can reinforce perceptions that legal expertise or representation is required to navigate the system.

“The exact information you need is always hidden on a page that’s hidden on another page. They need to make that simpler.”

- Disrepair and rent increase, Tribunal

“I don’t know if it’s my anxiety kind of thing, it would have been good to have wee tracker. These are the stages, it’s been lodged with the court, this is the rough timeframe.”

- Eviction and deposit issues, Tribunal

Engaging with the Tribunal is experienced as even more daunting when the landlord or letting agent is the one who initiates proceedings. Where this is the case, the tenant may have even less awareness of what the Tribunal is and how they can effectively engage with it or defend their case. This can lead to an immediate sense of panic and sense of being launched into a crisis situation. Another drawback of the Tribunal process is that there are long backlogs - an adviser cited four months. As discussed in the context of formal advice, advisers sometimes warn tenants that while the Tribunal is an option, there may be little point in making an application when their issue is urgent. It is recognised that the Tribunal is less effective for tenants who, for example, require an urgent repair.

“There were several months between me initially contacting them and Tribunal proceedings being raised.”

- Poor property condition, Advice only

While advisers emphasise that justice delayed is justice denied, tenants with both urgent and non-urgent issues are put off by the uncertainty that comes with the long waiting times associated with the Tribunal. This is especially the case for those who are facing other challenges in their life, or those who do not have access to ongoing advice or support and who may ultimately abandon the process.

“I hadn’t heard back in three months […] In the end I agreed to the rent increase […] For my own mental health, I couldn’t have just kept waiting and waiting and getting a barrage of emails saying you’ve got rent arrears.

I had to agree because I was getting really stressed out about it.”

- Rent increase, Tribunal

Participants who, following an application process, had their case processed by the Tribunal, found the experience with proceedings and staff largely positive. Tribunal staff are experienced as helpful, supportive, and professional, and the hearings themselves were said to be smooth and positive. Participants also describe being assigned caseworkers who help them understand ‘Tribunal talk’ and who ensure that the application contains all the necessary information to be processed.

While satisfaction ultimately depends on the process as a whole as well as the outcome, participants tended to be satisfied with the communication about their decision.

We note that some advisers expressed concerns relating to perceived inconsistencies in the approach to rulings. There is a belief that the outcome can be more or less favourable to landlords or tenants, depending on which members are dealing with the case. This is attributed to the wide variety of backgrounds that exists amongst Tribunal members, and a potential lack of uniformity in the training they receive. If outcomes for tenants vary depending on such factors, this presents a fairness issue, and can negatively impact on tenants’ confidence in the system.

Rent Service Scotland

Tenants have limited awareness of when and how they can challenge rent increases that they consider excessive. Most participants assume that there are no restrictions on the rent increases that a landlord can impose, as it is their property. Even amongst those who have experienced high rent increases, awareness of Rent Service Scotland is low.

“The [agent] said I’d have to take it to a Tribunal or whatever, so I emailed the Tribunal place.”

- Rent increases, Tribunal

Some participants had been informed that they should dispute their rent increase through the Tribunal, which they considered off-putting. While such advice would be accurate in relation to Short-Assured Tenancies, the majority of private contracts in Scotland are now Private Rented Tenancies, and landlords and letting agents should make tenants aware that they can apply to Rent Service Scotland.

Participants who engaged with Rent Service Scotland were generally positive about the application process, which requires them to complete an easily understandable form. Participants also voiced satisfaction about the brief period that passed before they were contacted by a Rent Officer.

However, both tenants and advisers expressed concerns over a lack of transparency and clarity regarding how and why decisions are made. This was due to a perceived lack of clarity or consistency in the rules that are being applied and criteria applied, as well as a lack of explanation when the decision is issued.

Advisers also raised concerns about the short window that tenants have if they wish to apply to Rent Service Scotland. At the time of fieldwork, tenants had 21 days after receiving the notification. In this time period, tenants have to come to terms with the notice, decide whether the increase is affordable and if they wish to challenge it, find out where and how to challenge this, and make an application. We note that following the passage of the Housing Bill in September 2025, tenants will have 30 days after receipt of the notification to inform the landlord that they deem the proposed increase to be above the permitted rate. If the parties do not agree, the tenant may then apply to Rent Service Scotland within 42 days following this. This should provide tenants with more time to challenge any undue rent increases in the future.

Local authority enforcement teams

When private tenants experience issues with their tenancy, there are multiple ways in which local authorities can assist:

- Advice and assistance: In some local authorities, there are private sector housing teams that provide advice around rights and responsibilities, eviction notices, property conditions, disputes and other matters. However, the existence or availability of such teams is not uniform across all local authorities.

- Third-party applications to the Tribunal: local authorities can make such applications on behalf of private tenants.[48] Only 10 out of Scotland’s 32 Local Authorities had submitted third-party applications in 2022/23. [49] Although this was an increase on seven the previous year, it suggests a disparity in how likely a private tenant is to receive assistance from their Local Authority in accessing the Tribunal, based on where they live. An understanding of why this is the case may result in improved outcomes for consumers.

- Enforcement: there are a number of other powers and duties local authorities have to help protect tenants, including:

-

- Issuing a work notice to require that the landlord brings a house in a reasonable state of repair when it considers this to be sub-standard

- If the Tribunal has issued a private landlord with a Repairing Standard Enforcement Order and the landlord still does not carry out the work, the Tribunal can send a failure to comply decision to the local authority. In that case, the local authority can carry out the necessary works and recover the cost from the landlord

- Remove a landlord who is no longer considered a fit and proper person from the register

-

In August 2025, Living Rent published a report arguing that such powers are currently underused, citing the City of Edinburgh Council as an example.[50] It may be helpful to gain an insight into the use of these powers by other local authorities across Scotland, to consider how the role they play in protecting private tenants can be optimised.

Tenants who have used local authority services mostly became aware that they could do so following either formal or informal advice and after failed efforts to resolve the issue directly with the landlord. Unless participants receive advice, they are often not aware that their council can play this role within the private rental sector.

Tenants initially found contacting their local authority enforcement team less complex than the Tribunal route, but there may be communication issues between different officers. The lack of a single point of contact means that they often have to explain their situation multiple times to different people.

“I was embarrassed, I thought, have I done something wrong here? Am I dirty or something like that? Even though I know that shouldn’t be the case at all. I felt vindicated when the Environmental Health people were saying this is a disgrace, a shambles, you shouldn’t be here. It felt like finally I had someone on my side for the first time with it all.”

- Poor property condition and urgent repairs, Tribunal

Participants generally experience inspections as a positive. While some felt ashamed about the condition of their property, they found that the inspector made them feel reassured.

However, tenants who use the local authority route had a fear of landlord retaliation, as most of them are still living in the home, and wish to continue living there. Ongoing support for those who have made a complaint is therefore important.

Tenants who engage with local authority teams have varying experiences, depending on the speed of the response, the perception of how thorough inspections are, and to what extent local authority involvement results in the landlord resolving the issue. These may reflect regional differences. If outcomes for tenants vary depending on the local authority they live in, this presents a fairness issue, and can negatively impact on tenants’ confidence in the system. Given the small number of participants in the research who used this pathway, further detailed research would be needed to establish the extent to which regional variations may exist and how these impact on tenant outcomes.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Information

Our research found that most tenants are unsure what their rights are, often assuming they do not have many. There is little clarity on when tenants should escalate issues, especially in relation to poor house conditions. While this is especially the case for first time private renters, our research found that this also applies to more experienced renters. There may be opportunities to improve awareness amongst both tenants and landlords. For example, the Scottish Government Model Private Residential Tenancy Agreement and accompanying guidance make no mention of damp or mould, which may feed into the misconception that landlords are not responsible for addressing such issues.

Tenants may not be familiar with advice services and what they can help with, and may not be aware of redress options. Combined with a fear of retaliation, this means that tenants often do not take action until they are reaching a crisis point, e.g. when mould starts taking a toll on their health or they are faced with eviction.

Tenants need clarity and confidence to raise issues with their landlords as soon as an issue occurs. There is a need to provide both tenants and landlords with understandable and practical information that is relevant to their circumstances and is accessible at the time and in the manner they need it.

We recommend that the Scottish Government undertakes further work with stakeholders to ensure that tenants and landlords have clarity on existing and new rights and obligations.

- The Scottish Government should work with stakeholders from across the housing sector to improve the ways tenants and landlords can find practical and/or tailored information about rights, access to advice services, and redress pathways.

- While the Scottish Government has information on its website, participants did not indicate much, if any, awareness of this. We recommend that the Scottish Government considers how to improve signposting towards sources of free and impartial advice for tenants and landlords. We also recommend undertaking user testing with tenants and landlords to identify potential improvements to the language and accessibility of information resources.

- We recognise that some improvements are dependent on the final scope of measures related to the Housing Bill that was passed in September 2025, secondary legislation, and other review processes that the Scottish Government has committed to. Discussions around these issues should specifically include thinking about how best to ensure tenants and landlords are aware of their rights.

- Following the passage of the Housing Bill, the Scottish Government should review the Model Private Tenancy Agreement and accompanying guidance to more clearly reflect the rights and obligations of tenants and landlords, in particular regarding repairs and maintenance, damp and mould, deposits, and rent increases. This should include considering the content and language of current tenancy agreements to identify what should be clarified, inserted, or simplified to help tenants and landlords better understand their rights and obligations, to reduce the possibility of ‘grey areas’. Revised drafts should be accessibility tested with tenants, advice bodies and landlords.

- Improvements could, for example, take the form of a short guide, including case studies, as an annex to the tenancy agreement, dedicated introductory guidance for newer renters, or interactive solutions such as a user portal. Tenants must receive relevant general information at the point they enter a tenancy highlighting issues they may be likely to encounter, and be able to easily access more tailored advice and solutions during their tenancy. The UK Government’s Behavioural Insights Team recently updated its EAST Framework, which helps public policymakers encourage behaviours by making them Easy, Attractive, Social, and Timely. Learnings might be taken from the updated framework.

- Tenants must be enabled to find information, to help them achieve early resolution wherever possible, minimising detriment and preventing escalation to crisis point.

Recommendation 2: Advice

While some tenants will be able to take action to resolve issues once provided with information, there will continue to be a demand for advice services to provide ongoing support for tenants seeking redress. This may be particularly relevant to tenants in vulnerable circumstances.

Our research found that tenants may be unaware of the nature and remit of different advice services, with tenants often assuming that services do not provide housing advice, or in any case that the advice provided is not for the type of issue they are facing. This may prevent tenants from seeking formal advice, and more tenants would benefit from such services if they were signposted appropriately.

This indicates a need to:

- Increase awareness of key advice services

- Increase awareness of what different advice services can assist with and how

- Ensure that tenants who need advice are signposted to the most appropriate free service to assist them with their issue

When appropriate, this should include signposting towards relevant tenancy information, guidance, and template letters, to help tenants resolve issues independently. This may help to alleviate existing pressures on advice services whilst empowering tenants.

Tenants across all communities in Scotland should be able to benefit from free advice and support when they need it. Advice services require adequate support and resourcing to deliver the necessary services. Not only will this limit emotional stress and financial detriment for tenants, but a preventive approach can also lead to earlier resolution of issues and less pressure on advice and redress systems.

Our research found that tenants who had accessed formal advice services had mixed experiences. Individual outcomes vary according to the issue experienced, the circumstances and personalities of the parties and their awareness of their rights. While tenants generally found accessing formal advice positive and empowering, some participants reported that they struggled to obtain an appointment due to services experiencing high demand.

The current advice landscape is facing pressures and the Scottish Government has recognised that a multi-year funding approach is needed to improve stability and enable more effective service delivery. We recognise that pilot projects are underway in this regard and it may be helpful if the next phase of the Scottish Government’s Fairer Funding pilot includes advice services that assist tenants facing issues with their tenancies.

We recommend that the Scottish Government works with partners to improve access to free and early advice to help tenants resolve issues they are facing.

- We recommend that the Scottish Government works with advice bodies, law centres, tenant unions, Tribunal staff and other relevant stakeholders, to explore how more personalised advice can be delivered to those who need it.

- Consumer Scotland is willing to take a lead role to facilitate discussions with advice agencies in the sector. These discussions could potentially explore whether there can be improvements in signposting, how best to facilitate referrals to more specialist services, or developing guidance that can help partners across the landscape to streamline the tenant advice journey.

- The Scottish Government should consider the inclusion of housing advice agencies in any future phases of the Fairer Funding pilot.

Recommendation 3: Ongoing Support

Providing ongoing support can be crucial when tenants are considering using the Tribunal or other formal processes, and it can help those who do embark upon a process to complete it. Tribunal applications in particular can be complex and time-consuming to navigate, and participants told us that they would not have started or completed this pathway without ongoing advice and support. In addition to formal advice, participants found guidance throughout the process by the Tribunal’s own staff to be helpful and positive.