The majority of domestic energy consumers in Great Britain face a significant increase in their gas and electricity bills in April, as the Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) - a taxpayer funded discount on household energy bills - is set to become less generous, and additional universal bill support ends. Under current forecasts this spike in household energy prices is set to be temporary, with the most recent analysis from Cornwall Insight suggesting that Ofgem’s default tariff cap could fall back to around £2,100 in the second half of 2023.

While a lot of uncertainty remains in these forward prices, there is nevertheless a strong case to maintain the current level of taxpayer support offered to households through the EPG to protect consumers from the financial stress that a significant, but temporary spike in bills would cause. An additional benefit of maintaining the EPG at its current level is that this is likely to mitigate a future rise in bad debt, which would ultimately have to be socialised across all consumers, raising bills for all.

The EPG and the Energy Bills Support Scheme (EBSS) have provided significant protection to energy consumers this winter.

The UK Government’s EPG effectively places a ceiling on the unit prices of gas and electricity to which domestic consumers in the United Kingdom are exposed. From October 2022 to March 2023 it was set at a level that implied that annual energy bills in Great Britain would be capped at £2,500 for a typical dual fuel consumer. In addition, consumers received a £400 discount on their energy bills through the EBSS.

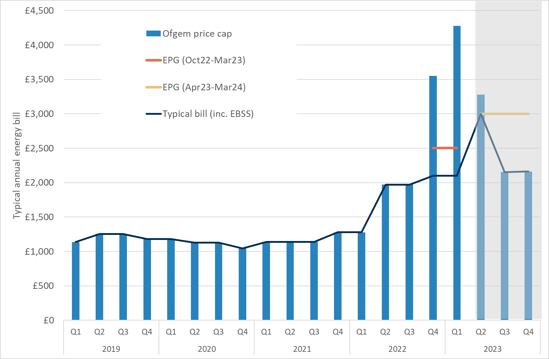

In combination the EPG and EBSS have provided significant protection relative to Ofgem’s default tariff cap, which would otherwise have set the price to which the majority of consumers in Great Britain would have been exposed. In the absence of these schemes the annual bill for a typical domestic gas and electricity consumer would have been £3,549 in the final quarter of 2022 and £4,279 in the first quarter of 2023 (see chart). The universal support offered through the EPG and the EBSS has limited these costs to £2,100, with the EPG credited by the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) as reducing inflation by as much as 2.5 percentage points.

But under current policy, consumers will face a significant spike in bills as support becomes less generous.

In April however, the EPG is set to increase to a level that implies an annual gas and electricity bill in Great Britain of £3,000 at typical use. At the same time, the EBSS will cease to apply. A typical domestic gas and electricity consumer in Great Britain will therefore see the price they pay for energy increase by almost 43% on the current already high levels.

Under current forecasts for Ofgem’s default tariff cap, this significant rise in bills will be temporary. Falling wholesale prices for gas and electricity imply that the Ofgem default tariff cap will fall back to around £2,100 in the second half of the year, if current trends are maintained (see chart). Significantly below the level of the EPG, at this level the default tariff cap would once again set the maximum price for gas and electricity for many consumers in Great Britain, and universal taxpayer support for domestic energy bills would reduce to zero.

Chart 1: Domestic energy costs net of government support are set to peak in the second quarter of 2023

Annual dual fuel energy bill for a typical consumer

Source: Consumer Scotland analysis of Ofgem and Cornwall Insight

Maintaining the EPG at its current level is justified to protect consumers from unprecedented short-term volatility.

On the basis of current forecasts and government policy, the price of energy that consumers in Great Britain will face – net of government support – is therefore set to be higher in Q2 2023 than at any time in history, and could be significantly higher than prices in Q1, or in the second half of the year.

There is a strong case for the government to maintain the EPG at its current rate to protect consumers from this volatility. Our latest energy consumer survey finds that over one third (35%) of consumers in Scotland are already finding it difficult to manage their energy bills with the EBSS in place and the EPG at £2,500.

Maintaining the EPG will also help to limit the impact of bad debt on the energy market and consumers.

Figures from Ofgem show that at the end of September 2022, 2.3 million households in Great Britain had fallen behind on their electricity payments. Of these, more than 40% did not have an active payment plan in place. For gas, Ofgem’s figures show that 1.9 million accounts were in arrears at the end of Q3 2022, over 39% of which had no payment plan in place. Before the winter heating season had even begun, domestic consumers therefore collectively owed their gas and electricity suppliers £2.5 billion, of which almost £1.6 billion was not under active repayment.

A significant proportion of this money will never be repaid, and will eventually be written off as bad debt. ‘Bad debt’ ultimately has to be socialised across all consumers, raising bills for all.

Furthermore, while bad debt is not a novel feature of today’s retail energy market, any significant increase in supplier bad debt is likely to put further pressure on margins that are already largely negative, and at sufficient scale could threaten the viability of suppliers’ ongoing participation in the market. This risks unloading further costs on all consumers as further consolidation in the retail energy market takes place.

Falling wholesale prices means that the EPG will cost the government less than it budgeted for, even if support is maintained at the current level.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) estimates the cost of maintaining the EPG at £2,500 would be £2.7 billion in the second quarter of 2023, before falling wholesale prices reduce the level of EPG subsidy to zero in Q3. While this appears costly, it should be viewed in the context that falling wholesale energy prices mean that the EPG is set to cost the government significantly less in 2023/2024 – even if the £2,500 cap is extended – than it had anticipated when it announced the scheme in Autumn 2022 (the IFS forecasts that the EPG will cost £4.6 billion in 2023/2024 if its level is retained at £2,500, compared to a forecast cost of £12.8 billion when the policy was announced last autumn, assuming recent wholesale market trends continue).

Whilst the fact that something has cost less than forecast is not in itself a reason to spend more on it, the point is that maintaining the EPG – a policy which can be justified in its own right – will not weaken the government’s fiscal position relative to autumn.

Summarising the case for intervention and the longer-term challenge.

In summary, there is a clear case for the government to protect consumers from the effects of a temporary spike in energy costs. The existing EPG and EBSS have provided this protection reasonably effectively this winter. Maintaining the EPG at its current rate is justified to provide that protection against ongoing volatility. Many consumers are not in a position to manage this volatility, but the government is.

In principle it would be more cost-effective to provide support targeted at those consumers who need support most. In practice, it is administratively challenging to implement a more targeted approach without a significant minority of at need customers missing out on support.

It is also important to remember that, although a typical bill is set to fall back to £2,100 in the second half of this year under current forecasts, that is nonetheless almost twice as high as the typical bill in 2021. This reiterates the importance of finding longer-term solutions to high energy prices, which are likely to persist for the foreseeable future.